The Unification of Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timeline / Before 1800 to After 1930 / ITALY

Timeline / Before 1800 to After 1930 / ITALY Date Country Theme 1800 - 1814 Italy Cities And Urban Spaces In the Napoleonic age, monumental architecture is intended to celebrate the glory of the new regime. An example of that is the Foro Bonaparte, in the area around the Sforza’s Castle in Milan (a project by Giovanni Antonio Antolini). 1800s - 1850s Italy Travelling The “Grand Tour” falls out of vogue; it used to be a period of educational travel, popular among the European aristocrats in the 17th and 18th centuries. Its primary destination was Italy. In the second half of the 19th century, vanguard artists no longer looked at Roman antiquities and Renaissance for inspiration. 1807 - 1837 Italy Cities And Urban Spaces In Milan, Luigi Cagnola completes the construction of the Arch of Peace, started during the Napoleonic age and inspired by the Arc du Carrousel in Paris. The stunning architectures of the Napoleonic age use arches, obelisks and allegorical groups of Roman and French classical inspiration. 1809 Italy Music, Literature, Dance And Fashion Giacomo Leopardi (1798–1837), philosopher, scholar and one of the greatest Italian poets of all times, writes his first poem. 1815 - 1816 Italy Rediscovering The Past Antonio Canova, acting on behalf of Pope Pio VII, recovers from France several pieces of art belonging to the Papal States, which had been brought to Paris by Napoleon, including the Villa Borghese’s archaeological collection. 1815 - 1860 Italy Political Context Italian “Risorgimento” (movement for national unification). 1815 Italy Political Context The Congress of Vienna decides the restoration of pre-Napoleonic monarchies: Kingdom of Sardinia (Piedmont, Genoa, Sardinia); Kingdom of Two Sicilies (Southern Italy and Sicily), the Papal States (part of Central Italy), Grand Duchy of Tuscany and other smaller states. -

Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1989 Between Two Amnesties: Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848 Leopold G. Glueckert Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Glueckert, Leopold G., "Between Two Amnesties: Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848" (1989). Dissertations. 2639. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2639 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1989 Leopold G. Glueckert BETWEEN TWO AMNESTIES: FORMER POLITICAL PRISONERS AND EXILES IN THE ROMAN REVOLUTION OF 1848 by Leopold G. Glueckert, O.Carm. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 1989 Leopold G. Glueckert 1989 © All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As with any paper which has been under way for so long, many people have shared in this work and deserve thanks. Above all, I would like to thank my director, Dr. Anthony Cardoza, and the members of my committee, Dr. Walter Gray and Fr. Richard Costigan. Their patience and encourage ment have been every bit as important to me as their good advice and professionalism. -

The Unification of Italy and Germany

EUROPEAN HISTORY Unit 10 The Unification of Italy and Germany Form 4 Unit 10.1 - The Unification of Italy Revolution in Naples, 1848 Map of Italy before unification. Revolution in Rome, 1848 Flag of the Kingdom of Italy, 1861-1946 1. The Early Phase of the Italian Risorgimento, 1815-1848 The settlements reached in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna had restored Austrian domination over the Italian peninsula but had left Italy completely fragmented in a number of small states. The strongest and most progressive Italian state was the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in north-western Italy. At the Congress of Vienna this state had received the lands of the former Republic of Genoa. This acquisition helped Sardinia-Piedmont expand her merchant fleet and trade centred in the port of Genoa. There were three major obstacles to unity at the time of the Congress of Vienna: The Austrians occupied Lombardy and Venetia in Northern Italy. The Papal States controlled Central Italy. The other Italian states had maintained their independence: the Kingdom of Sardinia, also called Piedmont-Sardinia, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (ruler by the Bourbon dynasty) and the Duchies of Tuscany, Parma and Modena (ruled by relatives of the Austrian Habsburgs). During the 1820s the Carbonari secret society tried to organize revolts in Palermo and Naples but with very little success, mainly because the Carbonari did not have the support of the peasants. Then came Giuseppe Mazzini, a patriotic writer who set up a national revolutionary movement known as Young Italy (1831). Mazzini was in favour of a united republic. -

Three Main Groups of People Settled on Or Near the Italian Peninsula and Influenced Roman Civilization

Three main groups of people settled on or near the Italian peninsula and influenced Roman civilization. The Latins settled west of the Apennine Mountains and south of the Tiber River around 1000 B.C.E. While there were many advantages to their location near the river, frequent flooding also created problems. The Latin’s’ settlements were small villages built on the “Seven Hills of Rome”. These settlements were known as Latium. The people were farmers and raised livestock. They spoke their own language which became known as Latin. Eventually groups of these people united and formed the city of Rome. Latin became its official language. The Etruscans About 400 years later, another group of people, the Etruscans, settled west of the Apennines just north of the Tiber River. Archaeologists believe that these people came from the eastern Mediterranean region known as Asia Minor (present day Turkey). By 600 B.C.E., the Etruscans ruled much of northern and central Italy, including the town of Rome. The Etruscans were excellent builders and engineers. Two important structures the Romans adapted from the Etruscans were the arch and the cuniculus. The Etruscan arch rested on two pillars that supported a half circle of wedge-shaped stones. The keystone, or center stone, held the other stones in place. A cuniculus was a long underground trench. Vertical shafts connected it to the ground above. Etruscans used these trenches to irrigate land, drain swamps, and to carry water to their cities. The Romans adapted both of these structures and in time became better engineers than the Etruscans. -

The Unification of Italy

New Dorp High School Social Studies Department AP Global Mr. Hubbs & Mrs. Zoleo The Unification of Italy While nationalism destroyed empires, it also built nations. Italy was one of the countries to form from the territories of the crumbling empires. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Austria ruled the Italian provinces of Venetia and Lombardy in the north, and several small states. In the south, the Spanish Bourbon family ruled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Nevertheless, between 1815 and 1848, increasing numbers of Italians were no longer content to live under foreign rulers. Amid growing discontent, two leaders appeared—one was idealistic, the other practical. They had different personalities and pursued different goals. But each contributed to the Unification of Italy. The Movement for Unity Begins In 1832, an idealistic 26-year-old Italian named Guiseppe Mazzini organized a nationalist group called, Young Italy. Similarly, youth were the leaders and custodians of the nineteenth century nationalist movements. The Napoleonic Wars were lead principally by younger men. Napoleon was 35 years of age when crowned Emperor. As nationalism spread across Europe the pattern continued. People over 40 were excluded from Mazzini's organization. During the violent year of 1848, revolts broke out in eight states on the Italian Peninsula. Mazzini briefly headed a republican government in Rome. He believed that nation-states were the best hope for social justice, democracy, and peace in Europe. However, the 1848 rebellions failed in Italy as they did elsewhere in Europe. The foreign rulers of the Italian states drove Mazzini and other nationalist leaders into exile. -

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome Beginnings Founding • The Latins, an Indo-European-speaking Italic people from central Europe, crossed the Alps about 1500 B.C. and invaded Italy. • Attracted by the warm climate and fertile land, the Latins conquered the native peoples and settled in central Italy. • On the seven hills overlooking the Tiber River, they founded the city of Rome. • (According to Roman legend, the city was founded in 753 B.C. by two descendants of the gods – the twin brothers Romulus and Remus) Life Among the Early Latins The early Latins, a simple, hardy people, • worked chiefly at farming and cattle-raising; • maintained close family ties, with the father exercising absolute authority; • worshipped tribal gods (Jupiter, the chief god; Mars, god of war; Neptune, god of the sea; and Venus, goddess of love), and • defended Rome against frequent attacks Etruscan Territory • Etruscan architecture was created between about 700 BC and 200 BC, when the expanding civilization of ancient Rome finally absorbed Etruscan civilization. The Etruscans were considerable builders in stone, wood and other materials of temples, houses, tombs and city walls, as well as bridges and roads. The only structures remaining in quantity in anything like their original condition are tombs and walls, but through archaeology and other sources we have a good deal of information on what once existed. Etruscan Architecture Etruscan Funeral Urns From Etruscan Rule to Independence Rome was captured about 750 B.C. by its northern neighbors, the Etruscans. From these more advanced people, the Latins, or Romans, learned to • construct buildings, roads and city walls, • make metal weapons, and • Apply new military tactics; The Romans in 500 B.C. -

Mcq Drill for Practice—Test Yourself (Answer Key at the Last)

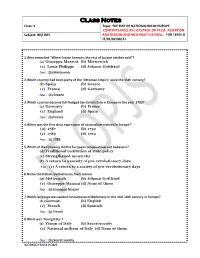

Class Notes Class: X Topic: THE RISE OF NATIONALISM IN EUROPE CONTENTS-MCQ ,FILL UPS,TRUE OR FALSE, ASSERTION Subject: HISTORY AND REASON AND MCQ PRACTICE DRILL… FOR TERM-I/ JT/01/02/08/21 1.Who remarked “When France Sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold”? (a) Giuseppe Mazzini (b) Metternich (c) Louis Philippe (d) Johann Gottfried Ans : (b) Metternich 2.Which country had been party of the ‘Ottoman Empire’ since the 15th century? (b) Spain (b) Greece (c) France (d) Germany Ans : (b) Greece 3.Which country became full-fledged territorial state in Europe in the year 1789? (c) Germany (b) France (c) England (d) Spain Ans : (b) France 4.When was the first clear expression of nationalism noticed in Europe? (a) 1787 (b) 1759 (c) 1789 (d) 1769 Ans : (c) 1789 5.Which of the following did the European conservatives not believe in? (d) Traditional institution of state policy (e) Strengthened monarchy (f) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days Ans : (c) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days 6.Name the Italian revolutionary from Genoa. (g) Metternich (b) Johann Gottfried (c) Giuseppe Mazzini (d) None of these Ans : (c) Giuseppe Mazzini 7.Which language was spoken for purposes of diplomacy in the mid 18th century in Europe? (h) German (b) English (c) French (d) Spanish Ans : (c) French 8.What was ‘Young Italy’ ? (i) Vision of Italy (b) Secret society (c) National anthem of Italy (d) None of these Ans : (b) Secret society WORKED FROM HOME 9.Treaty of Constantinople recognised .......... as an independent nation. -

By Filippo Sabetti Mcgill University the MAKING of ITALY AS AN

THE MAKING OF ITALY AS AN EXPERIMENT IN CONSTITUTIONAL CHOICE by Filippo Sabetti McGill University THE MAKING OF ITALY AS AN EXPERIMENT IN CONSTITUTIONAL CHOICE In his reflections on the history of European state-making, Charles Tilly notes that the victory of unitary principles of organiza- tion has obscured the fact, that federal principles of organization were alternative design criteria in The Formation of National States in West- ern Europe.. Centralized commonwealths emerged from the midst of autonomous, uncoordinated and lesser political structures. Tilly further reminds us that "(n)othing could be more detrimental to an understanding of this whole process than the old liberal conception of European history as the gradual creation and extension of political rights .... Far from promoting (representative) institutions, early state-makers 2 struggled against them." The unification of Italy in the nineteenth century was also a victory of centralized principles of organization but Italian state- making or Risorgimento differs from earlier European state-making in at least three respects. First, the prospects of a single political regime for the entire Italian peninsula and islands generated considerable debate about what model of government was best suited to a population that had for more than thirteen hundred years lived under separate and diverse political regimes. The system of government that emerged was the product of a conscious choice among alternative possibilities con- sidered in the formulation of the basic rules that applied to the organi- zation and conduct of Italian governance. Second, federal principles of organization were such a part of the Italian political tradition that the victory of unitary principles of organization in the making of Italy 2 failed to obscure or eclipse them completely. -

DO AS the SPANIARDS DO. the 1821 PIEDMONT INSURRECTION and the BIRTH of CONSTITUTIONALISM Haced Como Los Españoles. Los Movimi

DO AS THE SPANIARDS DO. THE 1821 PIEDMONT INSURRECTION AND THE BIRTH OF CONSTITUTIONALISM Haced como los españoles. Los movimientos de 1821 en Piamonte y el origen del constitucionalismo PIERANGELO GENTILE Universidad de Turín [email protected] Cómo citar/Citation Gentile, P. (2021). Do as the Spaniards do. The 1821 Piedmont insurrection and the birth of constitutionalism. Historia y Política, 45, 23-51. doi: https://doi.org/10.18042/hp.45.02 (Reception: 15/01/2020; review: 19/04/2020; acceptance: 19/09/2020; publication: 01/06/2021) Abstract Despite the local reference historiography, the 1821 Piedmont insurrection still lacks a reading that gives due weight to the historical-constitutional aspect. When Carlo Alberto, the “revolutionary” Prince of Carignano, granted the Cádiz Consti- tution, after the abdication of Vittorio Emanuele I, a crisis began in the secular history of the dynasty and the kingdom of Sardinia: for the first time freedoms and rights of representation broke the direct pledge of allegiance, tipycal of the absolute state, between kings and people. The new political system was not autochthonous but looked to that of Spain, among the many possible models. Using the extensive available bibliography, I analyzed the national and international influences of that 24 PIERANGELO GENTILE short historical season. Moreover I emphasized the social and geographic origin of the leaders of the insurrection (i.e. nobility and bourgeoisie, core and periphery of the State) and the consequences of their actions. Even if the insurrection was brought down by the convergence of the royalist forces and the Austrian army, its legacy weighed on the dynasty. -

Flavors of Southern Italy

FFllaavvoorrss ooff SSoouutthheerrnn IIttaallyy Rome * Amalfi Coast * Sicily With Capital Public Radio Insight Host Beth Ruyak June 16 - 28, 2017 “You may have the universe if I may have Italy.” Giuseppe Verdi Buongiorno! Dear friends, please join me, Beth Ruyak, Insight host for Capital Public Radio, and Italian guide extraordinaire, Natalia Mandelli, for a one-of-a-kind culturally rich, mouth-watering journey to Italy’s Deep South. Along the way, we will savor Spaghetti alle Vongole, fresh buffalo mozzarella and Sicily's rich olive oil. We’ll travel by ferry out to the gorgeous island of Capri; enjoy a classical music concert in Ravello, stroll through ancient Greek temples, elaborate Roman villas, Medieval Norman castles and colorful Moorish markets. Also included, an evening sunset cruise from the Naples to Sicily, wine tastings with the producers, colorful gardens and more! Join me, Capital Public Radio host Beth Ruyak, for what promises to be an extraordinary journey to Sicily and Southern Italy! Space is limited. Earthbound Expeditions Inc. POB 11305, Bainbridge Island, WA 98110 USA T. 800 723 8454 / T. 206 842 9775 / F. 206 238 8480 www.EarthboundExpeditions.com "God would have not have chosen Palestine if he had seen my kingdom of Sicily.” Frederick II YOUR JOURNEY 1 Night Historic Rome 3 Nights Ravello, Amalfi Coast 1 Night Sunset Cruise from Naples to Palermo 2 Nights Palermo, Capital of Sicily 1 Night Agrigento, Valley of the Temples 3 Nights Taormina, the Jewel of the Adriatic INSIDER EXPEREINCES Tickets to the Ravello Classical -

Unification of Italy 1792 to 1925 French Revolutionary Wars to Mussolini

UNIFICATION OF ITALY 1792 TO 1925 FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY WARS TO MUSSOLINI ERA SUMMARY – UNIFICATION OF ITALY Divided Italy—From the Age of Charlemagne to the 19th century, Italy was divided into northern, central and, southern kingdoms. Northern Italy was composed of independent duchies and city-states that were part of the Holy Roman Empire; the Papal States of central Italy were ruled by the Pope; and southern Italy had been ruled as an independent Kingdom since the Norman conquest of 1059. The language, culture, and government of each region developed independently so the idea of a united Italy did not gain popularity until the 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars wreaked havoc on the traditional order. Italian Unification, also known as "Risorgimento", refers to the period between 1848 and 1870 during which all the kingdoms on the Italian Peninsula were united under a single ruler. The most well-known character associated with the unification of Italy is Garibaldi, an Italian hero who fought dozens of battles for Italy and overthrew the kingdom of Sicily with a small band of patriots, but this romantic story obscures a much more complicated history. The real masterminds of Italian unity were not revolutionaries, but a group of ministers from the kingdom of Sardinia who managed to bring about an Italian political union governed by ITALY BEFORE UNIFICATION, 1792 B.C. themselves. Military expeditions played an important role in the creation of a United Italy, but so did secret societies, bribery, back-room agreements, foreign alliances, and financial opportunism. Italy and the French Revolution—The real story of the Unification of Italy began with the French conquest of Italy during the French Revolutionary Wars. -

Undiscovered Southern Italy: Puglia, Calabria, Lecce & Reggio

12 Days – 10 Nights $4,995 From BOS In DBL occupancy Springfield Museums presents: Undiscovered Southern Italy: Puglia, Calabria, Lecce & Reggio Travel Dates: April 24 to May 5, 2019 12 Days, 10 Nights accommodation, sightseeing, meals and airfare from Boston (BOS) Escape to Southern Italy for a treasure trove of art, ancient and prehistoric sites, cuisine and nature. Enchanting landscapes surround historic towns where Romanesque and Baroque cathedrals and monuments frame beautiful town squares in the shadows of majestic castles and noble palaces. This tour is enhanced by the rich, natural beauty of the rugged mountains and stunning coastline. Museum School at the Springfield Museums 21 Edward Street, Springfield, Ma. 01103 Contact: Jeanne Fontaine [email protected] PH: 413 314 6482 Day 1 - April 24, 2019: Depart US for Italy Depart the US on evening flight to Italy. (Dinner-in flight) (Breakfast-in flight) Day 2 - April 25, 2019: Arrive Reggio Calabria. Welcome to the southern part of the beautiful Italian peninsula. After collecting our bags and clearing customs, we’ll meet our Italian guide who will escort us throughout our trip. We will check-in to our centrally located Hotel in Reggio Calabria. The city owns what it fondly describes as "the most beautiful mile in Italy," a panoramic promenade along the shoreline that affords a marvelous view of the sea and the shoreline of Sicily some four miles across the straits. This coastal region flanked by highlands and rugged mountains, boasts a bounty of local food products thanks to its unique geography. After check in, enjoy free time to relax before our orientation tour of the city.