Tabriz on the Silk Roads: Thirteenth-Century Eurasian Cultural Connections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crimean Khanate, Ottomans and the Rise of the Russian Empire*

STRUGGLE FOR EAST-EUROPEAN EMPIRE: 1400-1700 The Crimean Khanate, Ottomans and the Rise of the Russian Empire* HALİL İNALCIK The empire of the Golden Horde, built by Batu, son of Djodji and the grand son of Genghis Khan, around 1240, was an empire which united the whole East-Europe under its domination. The Golden Horde empire comprised ali of the remnants of the earlier nomadic peoples of Turkic language in the steppe area which were then known under the common name of Tatar within this new political framework. The Golden Horde ruled directly över the Eurasian steppe from Khwarezm to the Danube and över the Russian principalities in the forest zone indirectly as tribute-paying states. Already in the second half of the 13th century the western part of the steppe from the Don river to the Danube tended to become a separate political entity under the powerful emir Noghay. In the second half of the 14th century rival branches of the Djodjid dynasty, each supported by a group of the dissident clans, started a long struggle for the Ulugh-Yurd, the core of the empire in the lower itil (Volga) river, and for the title of Ulugh Khan which meant the supreme ruler of the empire. Toktamish Khan restored, for a short period, the unity of the empire. When defeated by Tamerlane, his sons and dependent clans resumed the struggle for the Ulugh-Khan-ship in the westem steppe area. During ali this period, the Crimean peninsula, separated from the steppe by a narrow isthmus, became a refuge area for the defeated in the steppe. -

Gengis Kan Y La Formación Del Imperio Mongol Por Arturo Galindo García

GenGis Kan y la formación del imperio monGol por Arturo Galindo García fuentes primarias: Ramírez Medellín, L. (2011): Historia secreta de los mongoles , Miraguano Ediciones. Raymond Beazley, C. (1903) The Texts and Versions of John De Plano Carpini and William De Rubruquis, As Printed for the First Time by Hakluyt in 1598 , Together with Some Shorter Pieces Raymond Beazley, C & Hakluyt Society. obras de consulta: De Nicola, B. (2006-7): Las mujeres mongolas en los siglos XII y XIII un análisis sobre el rol de de la madre y la esposa de Chinggis Khan , en Acta Historica et Archaeologica Mediaevalia, Universidad de Barcelona. Turnbull, S. (2003): The mongol Warrior: 1200 – 1350 , Osprey Publishing. Weatherford, J. (2006): Genghis Khan y el inicio del mundo moderno , Ediciones Crítica. Palazuelos, E. (2001): El poder sin metáfora: el imperio de Genghis Khan , Siglo XXI de España Editores. Aigle, D. (2004): Loi mongole vs loi islamique. Entre mythe et réalité , en Annales Histoire Sciences sociales , Éditions de l’École des hautes etudes en sciences sociales. la conquista y destrucción del imperio jorasmio por Borja Pelegero fuentes primarias: Juvaini, A., Genghis Khan. The history of the world conqueror. Boyle, J., A., (Trad.) Manchester University Press. Manchester, (1958) 1997. Ramírez, L., (Trad.). Historia secreta de los mongoles . Miraguano Ediciones. Madrid, 2000. Rashid al-Din, Histoire des Mongols de la Perse. Quatrèmere, M., A., Oriental Press. Amsterdam, 1968. fuentes secundarias: Akhinzanov, S., M., «Kipcaks and Khwarazm» en Seaman, G.; Marks, D., Rulers from the steppe. State formation on the Eurasian periphery. Ethno - graphics Press. Los Angleles, 1991. Barfield, T ., The perilous frontier: nomadic empires and China . -

A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today

Volume: 8 Issue: 2 Year: 2011 A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today Ercan Karakoç Abstract After initiation of the glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) policies in the USSR by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union started to crumble, and old, forgotten, suppressed problems especially regarding territorial claims between Azerbaijanis and Armenians reemerged. Although Mountainous (Nagorno) Karabakh is officially part of Azerbaijan Republic, after fierce and bloody clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the entire Nagorno Karabakh region and seven additional surrounding districts of Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Jabrail, Fizuli, Khubadly and Zengilan, it means over 20 per cent of Azerbaijan, were occupied by Armenians, and because of serious war situations, many Azerbaijanis living in these areas had to migrate from their homeland to Azerbaijan and they have been living under miserable conditions since the early 1990s. Keywords: Karabakh, Caucasia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire, Russia and Soviet Union Assistant Professor of Modern Turkish History, Yıldız Technical University, [email protected] 1003 Karakoç, E. (2011). A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today. International Journal of Human Sciences [Online]. 8:2. Available: http://www.insanbilimleri.com/en Geçmişten günümüze Karabağ tarihi üzerine bir değerlendirme Ercan Karakoç Özet Mihail Gorbaçov tarafından başlatılan glasnost (açıklık) ve perestroyka (yeniden inşa) politikalarından sonra Sovyetler Birliği parçalanma sürecine girdi ve birlik coğrafyasındaki unutulmuş ve bastırılmış olan eski problemler, özellikle Azerbaycan Türkleri ve Ermeniler arasındaki sınır sorunları yeniden gün yüzüne çıktı. Bu bağlamda, hukuken Azerbaycan devletinin bir parçası olan Dağlık Karabağ bölgesi ve çevresindeki Laçin, Kelbecer, Cebrail, Agdam, Fizuli, Zengilan ve Kubatlı gibi yedi semt, yani yaklaşık olarak Azerbaycan‟ın yüzde yirmiye yakın toprağı, her iki toplum arasındaki şiddetli ve kanlı çarpışmalardan sonra Ermeniler tarafından işgal edildi. -

The Last Empire of Iran by Michael R.J

The Last Empire of Iran By Michael R.J. Bonner In 330 BCE, Alexander the Great destroyed the Persian imperial capital at Persepolis. This was the end of the world’s first great international empire. The ancient imperial traditions of the Near East had culminated in the rule of the Persian king Cyrus the Great. He and his successors united nearly all the civilised people of western Eurasia into a single state stretching, at its height, from Egypt to India. This state perished in the flames of Persepolis, but the dream of world empire never died. The Macedonian conquerors were gradually overthrown and replaced by a loose assemblage of Iranian kingdoms. The so-called Parthian Empire was a decentralised and disorderly state, but it bound together much of the sedentary Near East for about 500 years. When this empire fell in its turn, Iran got a new leader and new empire with a vengeance. The third and last pre-Islamic Iranian empire was ruled by the Sasanian dynasty from the 220s to 651 CE. Map of the Sasanian Empire. Silver coin of Ardashir I, struck at the Hamadan mint. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Silver_coin_of_Ardashir_I,_struck_at_the_Hamadan _mint.jpg) The Last Empire of Iran. This period was arguably the heyday of ancient Iran – a time when Iranian military power nearly conquered the eastern Roman Empire, and when Persian culture reached its apogee before the coming of Islam. The founder of the Sasamian dynasty was Ardashir I who claimed descent from a mysterious ancestor called Sasan. Ardashir was the governor of Fars, a province in southern Iran, in the twilight days of the Parthian Empire. -

Koshymova Aknur the Role of Oghuzes in the VIII-XIII Centuries In

Koshymova Aknur The role of Oghuzes in the VIII-XIII centuries in the formation of ethno genesis of Turkic peoples ANNOTATION To the dissertation prepared to get PhD degree in “History” – 6D020300 General description of the dissertation. The dissertation paper explores the place of Oghuz in the ethnogenesis of the Turkic peoples in the context of the history of the Kazakhs, Azerbaijanis, Turkmen, Kyrgyz, and Turks. The relevance of the research. The studied problem reflects one of the topical issues that has a peculiar place both in national history and foreign historiography. Due to the antiquity and deep historical roots of the ethnogenetic process of the formation of the late Turkic peoples, the researchers recognized the direct involvement of the Oghuz clans and tribes in the history of the Kazakhs. During the study of the ethnogenesis of a single Turkic people, the process of its formation, development paths and features, you can see how great the role of migration and assimilation processes in the content of ethnic mixing of the autochthonous population and alien tribes, which determined the future ethnic composition, language, culture, and this circumstance allows us to consider this factor as the leading one. Therefore, the history of the Oghuz-speaking peoples who inhabited Central and Asia Minor, the Caucasus, from a modern point of view, must be investigated in close connection with the history of the Kazakh people, which makes it possible to obtain valuable scientific results. The history of the Oghuz originating in the VIII century from the territories of the Mongolian plateau and the northeastern part of modern Kazakhstan, which as a result of mass movements occupied the Syrdarya valley, then the territory of modern Turkmenistan, then Azerbaijan and Anatolia, which led to dramatic changes in ethnic processes in these regions, it is necessary to consider taking into account the historical and genetic continuity. -

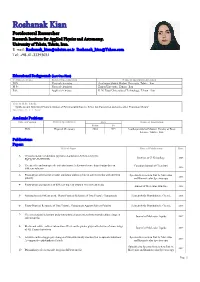

Roshanak Kian Postdoctoral Researcher Research Institute for Applied Physics and Astronomy, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

Roshanak Kian Postdoctoral Researcher Research Institute for Applied Physics and Astronomy, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Tel: +98-41-33393031 Educational Background: (Last One First) Certificate Degree Field of Specialization Name of Institution Attended PhD Physical chemistry Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University, Tabriz - Iran M.Sc. Physical chemistry Zanjan University, Zanjan - Iran B.Sc. Applied chemistry K. N. Toosi University of Technology, Tehran - Iran Title of M.Sc. Thesis: “ Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Pyridinocalix(4)arene Silver Ion Complexes and some other Transition Metals” Supervisors: Dr. A. A. Torabi Academic Positions: Title of Position Field of Specialization Date Name of Institution From To PhD Physical Chemistry 2010 2015 Azarbaijan Shahid Madani- Faculty of Basic Science, Tabriz - Iran. Publications: Papers: Title of Paper Place of Publication Date 1- Crystal structure of dichloro (pyridine-2-aldoxime-N,N)mercury(II): JOURNAL OF Z. Kristallogr 2005 HgCl2(NC5H4CHNOH) 2- The specific and non-specific solvatochromic behavior of some diazo Sudan dyes in Canadian Journal of Chemistry 2015 different solvents 3- Photo-physical behavior of some antitumor anthracycline in solvent media with different Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular 2014 polarity and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 4- Photo-physical properties of different types of vitamin A in solvent media Journal of Molecular Structure 2015 5- Solvatochromic Effects on the Photo-Physical -

The Coming Turkish- Iranian Competition in Iraq

UNITeD StateS INSTITUTe of Peace www.usip.org SPeCIAL RePoRT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Sean Kane This report reviews the growing competition between Turkey and Iran for influence in Iraq as the U.S. troop withdrawal proceeds. In doing so, it finds an alignment of interests between Baghdad, Ankara, and Washington, D.C., in a strong and stable Iraq fueled by increased hydrocarbon production. Where possible, the United States should therefore encourage The Coming Turkish- Turkish and Iraqi cooperation and economic integration as a key part of its post-2011 strategy for Iraq and the region. This analysis is based on the author’s experiences in Iraq and Iranian Competition reviews of Turkish and Iranian press and foreign policy writing. ABOUT THE AUTHO R in Iraq Sean Kane is the senior program officer for Iraq at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). He assists in managing the Institute’s Iraq program and field mission in Iraq and serves as the Institute’s primary expert on Iraq and U.S. policy in Iraq. Summary He previously worked for the United Nations Assistance Mission • The two rising powers in the Middle East—Turkey and Iran—are neighbors to Iraq, its for Iraq from 2006 to 2009. He has published on the subjects leading trading partners, and rapidly becoming the most influential external actors inside of Iraqi politics and natural resource negotiations. The author the country as the U.S. troop withdrawal proceeds. would like to thank all of those who commented on and provided feedback on the manuscript and is especially grateful • Although there is concern in Washington about bilateral cooperation between Turkey and to Elliot Hen-Tov for generously sharing his expertise on the Iran, their differing visions for the broader Middle East region are particularly evident in topics addressed in the report. -

Protagonist of Qubilai Khan's Unsuccessful

BUQA CHĪNGSĀNG: PROTAGONIST OF QUBILAI KHAN’S UNSUCCESSFUL COUP ATTEMPT AGAINST THE HÜLEGÜID DYNASTY MUSTAFA UYAR* It is generally accepted that the dissolution of the Mongol Empire began in 1259, following the death of Möngke the Great Khan (1251–59)1. Fierce conflicts were to arise between the khan candidates for the empty throne of the Great Khanate. Qubilai (1260–94), the brother of Möngke in China, was declared Great Khan on 5 May 1260 in the emergency qurultai assembled in K’ai-p’ing, which is quite far from Qara-Qorum, the principal capital of Mongolia2. This event started the conflicts within the Mongolian Khanate. The first person to object to the election of the Great Khan was his younger brother Ariq Böke (1259–64), another son of Qubilai’s mother Sorqoqtani Beki. Being Möngke’s brother, just as Qubilai was, he saw himself as the real owner of the Great Khanate, since he was the ruler of Qara-Qorum, the main capital of the Mongol Khanate. Shortly after Qubilai was declared Khan, Ariq Böke was also declared Great Khan in June of the same year3. Now something unprecedented happened: there were two competing Great Khans present in the Mongol Empire, and both received support from different parts of the family of the empire. The four Mongol khanates, which should theo- retically have owed obedience to the Great Khan, began to act completely in their own interests: the Khan of the Golden Horde, Barka (1257–66) supported Böke. * Assoc. Prof., Ankara University, Faculty of Languages, History and Geography, Department of History, Ankara/TURKEY, [email protected] 1 For further information on the dissolution of the Mongol Empire, see D. -

Continuity and Change in the Mongol Army of the Ilkhanate

CHAPTER 2 Continuity and Change in the Mongol Army of the Ilkhanate Reuven Amitai One of the important trends of late medieval societies in much of the Islamic world is that the military elite became increasingly identified with the political ruling class. This tendency possibly reached its height in the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt and Syria. One cannot go quite so far when describing the nature of Mongol rule in Iran and the surrounding countries, but it would be fair to state that the army was the most important institution in the Ilkhanid state (and Mongol states as a whole). It is thus not surprising that the study of mili- tary aspects of the Ilkhanate (and the Mongol armies that preceded it) have received some serious attention in modern scholarship. Mention can be made of the important studies on the Mongol armies in the Middle East (some of them parts of larger works) by Bertold Spuler,1 David Morgan,2 C. E. Bosworth,3 John M. Smith, Jr.4 and Arsenio Martinez.5 To this can be added very useful studies on the Mongol army as a whole by H. Desmond Martin,6 S. R. Turnbull,7 Robert Reid,8 Witold Świętosławski,9 Timothy May,10 and others, which help us understand the background of much of the Mongol military activity in the countries today known as the Middle East. My own contributions to the study of the Mongol military machine have generally been in connection with the ongoing Ilkhanid war with the Mamluks, and I have tried to put this war in 1 Spuler, Die Mongolen in Iran, 330–48. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi POWER, POLITICS, AND TRADITION IN THE MONGOL EMPIRE AND THE ĪlkhānaTE OF IRAN OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Īlkhānate of Iran MICHAEL HOPE 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6D P, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Michael Hope 2016 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2016932271 ISBN 978–0–19–876859–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Mulan's Sisters on the Steppes of Inner Asia

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Winter 2021 Mulan's Sisters on the Steppes of Inner Asia Zoe Hoff Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Chinese Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hoff, Zoe, "Mulan's Sisters on the Steppes of Inner Asia" (2021). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 443. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/443 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mulan’s Sisters on the Steppes of Inner Asia Zoe Hoff Mulan’s Sisters on the Steppes of Inner Asia 0 Mulan’s Sisters on the Steppes of Inner Asia Zoe Hoff Intro Sedentary Practices and Expectations As cultures change so too do the dynamics within them, one of the most polarizing being the relationship between men and women. Each culture has adapted gender issues differently. This paper will focus on such gender issues within some of the historically nomadic populations in Inner Asia over a long period of time. In Inner Asia there were women who exercised their powers in different ways The Northern Wei (386-534 CE), which was a sedentary society established by the Taghbach, a nomadic people, that had female rulers. The story of Mulan shows a side of culture, women participating in war in Inner Asia, that is not often talked about.