Binding Waste As Book History Patterns of Survival Among the Early Mainz Donatus Editions Eric Marshall White Princeton University Library, US

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colin Mcallister Regnum Caelorum Terrestre: the Apocalyptic Vision of Lactantius May 2016

Colin McAllister Regnum Caelorum Terrestre: The Apocalyptic Vision of Lactantius May 2016 Abstract: The writings of the early fourth-century Christian apologist L. Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius have been extensively studied by historians, classicists, philosophers and theologians. But his unique apocalyptic eschatology expounded in book VII of the Divinae Institutiones, his largest work, has been relatively neglected. This paper will distill Lactantius’s complex narrative and summarize his sources. In particular, I investigate his chiliasm and the nature of the intermediate state, as well as his portrayal of the Antichrist. I argue that his apocalypticism is not an indiscriminate synthesis of varying sources - as it often stated - but is essentially based on the Book of Revelation and other Patristic sources. +++++ The eminent expert on all things apocalyptic, Bernard McGinn, wrote: Even the students and admirers of Lactantius have not bestowed undue praise upon him. To Rene Pichon [who wrote in 1901 what is perhaps still the seminal work on Lactantius’ thought] ‘Lactantius is mediocre in the Latin sense of the word - and also a bit in the French sense’; to Vincenzo Loi [who studied Lactantius’ use of the Bible] ‘Lactantius is neither a philosophical or theological genius nor linguistic genius.’ Despite these uneven appraisals, the writings of the early fourth-century Christian apologist L. Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius [c. 250-325] hold, it seems, a little something for everyone.1 Political historians study Lactantius as an important historical witness to the crucial transitional period from the Great Persecution of Diocletian to the ascension of Constantine, and for insight into the career of the philosopher Porphyry.2 Classicists and 1 All dates are anno domini unless otherwise indicated. -

The German Teacher's Companion. Development and Structure of the German Language

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 285 407 FL 016 887 AUTHOR Hosford, Helga TITLE The German Teacher's Companion. Development and Structure of the German Language. Workbook and Key. PUB DATE 82 NOTE 640p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) -- Reference Materials General (130) EDRS PRICE MF03/PC26 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Comparative Analysis; Contrastive Linguistics; Diachronic Linguistics; English; *German; *Grammar; Language Teachers; Morphology (Languages); *Phonology; Reference Materials; Second Language Instruction; *Syntax; Teacher Elucation; Teaching Guides; Textbooks; Workbooks ABSTRACT This complete pedagogical reference grammar for German was designed as a textbook for advanced language teacher preparation, as a reference handbook on the structure of the German language, and for reference in German study. It systematically analyzes a d describes the language's phonology, morphology, and syntax, and gives a brief survey of its origins and development. German and English structures are also compared and contrasted to allow understanding of areas of similarity or difficulty. The analysis focuses on insights useful to the teacher rather than stressing linguistic theory. The materials include a main text/reference and a separate volume containing a workbook and key. The workbook contains exercises directly related to the text. (MSE) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** THE GERMAN TEACHER'S COMPANION Development and Structure of the German Language Helga Hosford University of Montana NEWBURY HOUSE PUBLISHERS, INC. ROWLEY, MASSACHUSETTS 01969 ROWLEY LONDON TOKYO 1 9 8 2 3 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Hosford, Helga, 1937 - The German teacher's companion Bibliography p Includes index. -

Reformation 2017 Johannes Gutenberg Handout

FACES OF THE REFORMATION Gutenberg’s invention helped Johannes Gutenberg spread the ideas of the Reformation Born: 1395? | Mainz, Germany to the masses Died: 1468 | Mainz, Germany Could Johannes Gutenberg have known when he first conceived the idea of moveable type that it would contribute to the spread of the Reformation and the Renaissance and lead to the education of all levels of society? One might question his presence in the “Faces of the Reformation” series. But considering that his presses printed not only Luther’s 95 Theses but also the papal indulgences that sparked Luther’s polemic pen, it seems fitting that he should be included. Gutenberg was born about 1395 as the son of a metalsmith, and he became acquainted with the printing business at a very young age. His invention of the moveable type press made the mass production of books a reality that would change the world. By 1450, his new invention was operating. As with most new ideas of this scale, the road was not smooth. In 1446, Johann Fust, Gutenburg’s financial backer, won a lawsuit against him regarding repayment of the funds. Gutenberg’s employee and son-in-law, Peter SchÖffer, testified against him. Before this lawsuit was finalized, Gutenberg had printed a Latin Bible that contained 42 lines of Scripture per page. This “42-line Bible” is known as the Gutenberg Bible. The press for the Bible, Gutenberg’s masterpiece, along with a second book containing only Psalms, was lost to Fust in the court case. The Psalter was published after the court case with no mention of Gutenberg; only Fust’s and SchÖffer’s names appear as the printers. -

Download Als

www.bayerisch-schwaben.de Genau das Richtige Dillinger Land Landkreis Donau-Ries für Dich! Zentrum des Schwäbischen Ferienland mit Jena / Leipzig / Donautals K ratergeschichte Saalfeld Herzlich willkommen in Bayerisch-Schwaben! Mit dieser Faltkarte nehmen wir Sie mit auf eine Entdeckungreise Plauen / durch unsere bodenständige Destination, die Bayern und Für Naturliebhaber ist das Dillinger Land eine wahre Einmalige Landschaften,Fladungen Städte vollerMeiningen Geschichte, / präch- Neuhaus Ludwigsstadt Gera / Dresden Erfurt Schwaben perfekt vereint. Schatztruhe. Auf einer Distanz von knapp 20 Kilometern tige Schlösser, Kirchen und Klöster, spannende Geologie,Meiningen Bayerisch-Schwaben – das sind die UNESCO-Welterbe- treffen hier verschiedenste Landschaften aufeinander, kulturelle VielfaltMellrichstadt und kulinarische Bf Genüsse: Das alles Sonneberg Nordhalben Feilitzsch Stadt Augsburg & sechs spannende Regionen. Hier liegen die von den Ausläufern der Schwäbischen Alb über das weite lässt sich im Ferienland Donau-Ries erlebnisreich zu Fuß, (Thür) Hbf Bad Steben Wurzeln der Wittelsbacher genauso wie weite Wälder und fruchtbare Donautal bis zum voralpinen Hügelland. Ob per Rad oder mit dem Auto entdecken. Neustadt (b. Coburg) Flussauen mit herrlichen Rad- & Wanderwegen. Großarti- gemütlicher Genussradler, Mountainbiker oder Wanderer, Fulda / Hof Hbf Schlüchtern Bad Neustadt ge Kulturschätze in Kirchen, Klöstern, Schlössern und Mu- hier kommen alle auf ihre Kosten. Unberührte Auwälder Als besonderes Highlight lohnt(Saale) die EntdeckungBad -

Provenienzen Von Inkunabeln Der BSB

Provenienzen von Inkunabeln der BSB Nähere historisch-biographische Informationen zu den einzelnen Vorbesitzern sind enthalten in: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek: Inkunabelkatalog (BSB-Ink). Bd. 7: Register der Beiträger, Provenienzen, Buchbinder. [Redaktion: Bettina Wagner u.a.]. Wiesbaden: Reichert, 2009. ISBN 978-3-89500-350-9 In der Online-Version von BSB-Ink (http://inkunabeln.digitale-sammlungen.de/sucheEin.html) können die in der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek vorhandenen Inkunabeln aus dem Besitz der jeweiligen Institution oder Person durch Eingabe des Namens im Suchfeld "Provenienz" aufgefunden werden. Mehrteilige Namen sind dabei in Anführungszeichen zu setzen; die einzelnen Bestandteile müssen durch Komma getrennt werden (z.B. "Abensberg, Karmelitenkloster" oder "Abenperger, Hans"). 1. Institutionen Ort Institution Patrozinium Abensberg Karmelitenkloster St. Maria (U. L. Frau) Aichach Stadtpfarrkirche Beatae Mariae Virginis Aldersbach Zisterzienserabtei St. Maria, vor 1147 St. Petrus Altdorf Pfarrkirche Altenhohenau Dominikanerinnenkloster Altomünster Birgittenkloster St. Peter und Paul Altötting Franziskanerkloster Altötting Kollegiatstift St. Maria, St. Philipp, St. Jakob Altzelle Zisterzienserabtei Amberg Franziskanerkloster St. Bernhard Amberg Jesuitenkolleg Amberg Paulanerkloster St. Joseph Amberg Provinzialbibliothek Amberg Stadtpfarrkirche St. Martin Andechs Benediktinerabtei St. Nikolaus, St. Elisabeth Angoulême Dominikanerkloster Ansbach Bibliothek des Gymnasium Carolinum Ansbach Hochfürstliches Archiv Aquila Benediktinerabtei -

Angelo Maria Bandini in Viaggio a Roma (1780-1781)

Biblioteche & bibliotecari / Libraries & librarians ISSN 2612-7709 (PRINT) | ISSN 2704-5889 (ONLINE) – 3 – Biblioteche & bibliotecari / Libraries & librarians Comitato Scientifico / Editorial board Mauro Guerrini, Università di Firenze (direttore) Carlo Bianchini, Università di Pavia Andrea Capaccioni, Università di Perugia Gianfranco Crupi, Sapienza Università di Roma Tom Delsey, Ottawa University José Luis Gonzalo Sánchez-Molero, Universidad Complutense de Madrid Graziano Ruffini, Università di Firenze Alberto Salarelli, Università di Parma Lucia Sardo, Università di Bologna Giovanni Solimine, Sapienza Università di Roma La collana intende ospitare riflessioni sulla biblioteconomia e le discipline a essa connesse, studi sulla funzione delle biblioteche e sui suoi linguaggi e servizi, monografie sui rapporti fra la storia delle biblioteche, la storia della biblioteconomia e la storia della professione. L’attenzione sarà rivolta in particolare ai bibliotecari che hanno cambiato la storia delle biblioteche e alle biblioteche che hanno accolto e promosso le figure di grandi bibliotecari. The series intends to host reflections on librarianship and related disci- plines, essays on the function of libraries and its languages and services, monographs on the relationships between the history of libraries, the his- tory of library science and the history of the profession. The focus will be on librarians who have changed the history of libraries and libraries that have welcomed and promoted the figures of great librarians. Fiammetta Sabba Angelo -

Digitization and Presentation of Music Documents in the Bavarian State

ISSN 0015-6191 61/3 July–September 2014 Journal of the International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML) Journal de l’Association Internationale des Bibliothèques, Archives et Centres de Documentation Musicaux (AIBM) Zeitschrift der Internationalen Vereinigung der Musikbibliotheken, Musikarchive und Musikdocumentationzentren (IVMB) Editor-in-Chief Maureen Buja, Ph.D., G/F, No. 156, Lam Tsuen San Tsuen, Tai Po, NT, Hong Kong; Telephone: +852-2146-8047; email: [email protected] Assistant editor Rupert Ridgewell, Ph.D., Music Collections, The British Library, 96 Euston Rd., London NW1 2DB, England; e-mail: [email protected] Book Review Editors Senior Book Review Editor Mary Black Junttonen, Music Librarian, Michigan State University Libraries, 366 W. Circle Drive, Room 410, East Lansing, MI 48824 USA. Telephone: +1-517-884-0859, e-mail: [email protected] Colin Coleman, Gerald Coke Handel Collection, The Foundling Museum, 40 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AZ, UK. Telephone: +44(0)20 7841 3615, e-mail: [email protected] John R. Redford (US) Gerald Seaman (Oxford) Editorial Board: Joseph Hafner, (Co-Chair, IAML Publications Committee, McGill University, Montréal, Canada); Georgina Binns (Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne, Australia); Thomas Kalk (Stadtbüchereien Düsseldorf – Musikbibliothek, Düsseldorf ); Daniel Paradis (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, Montréal, QC, Canada) Advertising manager: Kathleen Haefliger, 9900 S. Turner Ave., Evergreen Park, -

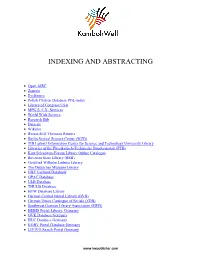

Indexing and Abstracting

INDEXING AND ABSTRACTING Open AIRE Zenodo EyeSource Polish Citation Database POL-index Library of Congress USA MPG S. F.X- Services World Wide Science Research Bib Datacite Wikidot ResearchID Thomson Reuters Berlin Scocial Science Center (WZB) TIB Leibniz Information Center for Science and Technology University Library Libraries of the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) Kurt-Schwitters-Forum Library Online Catalogue Bavarian State Library (BSB) Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Library The Deutsches Museum Library HBZ Verbund Databank OPAC Database ULB Database THULB Database HTW Database Library German Central Interal Library (BVB) German Union Catalogue of Serials (ZDB) Southwest German Library Association (SWB) HEBIS Portal Library, Germany GVK Database Germany HUC Database Germany KOBV Portal Database Germany LIVIVO Search Portal Germany www.kwpublisher.com Regional Catalog Stock Germany UBBraunchweig Library Germany UB Greifswald Library Germany TIB Entire Stock Germany The German National Library of Medicine (ZB MED) Library of the Wissenschaftspark Albert Einstein Max Planck Digital Library Gateway Bayern GEOMAR Library of Ocean Research Information Access Global Forum on Agriculture Research Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Library Libraries of the Leipzig University Library of Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Germany Library of the Technical University of Central Hesse Library of University of Saarlandes, Germany Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt (ULB) Jade Hochschule Library -

AUGUSTINUS HIPPONENSIS, Enarrationes in Psalmos CXX-CXXXIII in Latin, Decorated Manuscript on Parchment Northern Italy, Likely Milan (Abbey of Morimondo?), C

AUGUSTINUS HIPPONENSIS, Enarrationes in Psalmos CXX-CXXXIII In Latin, decorated manuscript on parchment Northern Italy, likely Milan (Abbey of Morimondo?), c. 1150-1175 99 ff., preceded and followed by a modern parchment flyleaf, missing at least a quire at the beginning (collation: i-xii8, xiii3), written by a single scribe above the top line in a twelfth-century relatively angular minuscule in brown ink, text copied on 25 lines (justification: 115/125 x 75 mm), added explicits and chapter headings at the end of each textual division in a different rounded script (most in pale brown ink, some in pale red ink), prickings in outer margins, ruled in hard point, catchwords on ff. 32v and 40v, rubrics in bright red, liturgical lessons marked in the margins in red or brown ink roman numerals (sometimes preceded by the letter “lc” for “lectio” (e.g. f. 8), some initials and capitals stroked in red, larger painted 3-line high initials in red, one 4-line high initial in green with downward extension for a further eight lines, some with ornamental flourishing (e.g. f. 82v), some contemporary annotations and/or corrections. Bound in a modern tanned pigskin binding over wooden boards, renewed parchment pastedown and flyleaves, brass catches and clasps, fine restored condition (some leaves cropped a bit shorter, a few waterstains in bottom right corner of a number of folios, never affecting legibility). Dimensions 165 x 105 mm. Twelfth-century copy of the middle section of the important and influential exegetical treatise devoted to the Psalms, Augustine’s longest work. The codex boasts a twelfth-century ex-libris from the abbey of Morimondo, and it appears in the Morimondo Library Catalogue datable to the third quarter of the twelfth century. -

M4rnlnguttl ~Nut41y Con Tinning LEHRE UND WEHRE MAGAZIN FUER EV.-LUTH

Qtnurnr~itt m4rnlnguttl ~nut41y Con tinning LEHRE UND WEHRE MAGAZIN FUER EV.-LUTH. HOMlLETIK THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY-THEOLOGICAL MONTHLY Vol. V June, 1934 No.6 CONTENTS p ~ e Die rechte Mitte in der Liturgie und Ordnung des Gottes dienstes. L. Fuerbringer. • . • • • • • • • . • • • • • . • • • • • . .• 417 The Story of the German Bible. P. E. Krel mann . • ••••.•• , 425 Zur Lehre von der Reue. Th. E n~ ,lder .• . ••.•.••••••.••• 445 Der Pastor in seinem Verhaeltnis zu seintn Amtsnachbarn. \V'1. H e' ne . • . • • . • • •• 4~ 6 Sermons and Outlines ... 466 Theological Observer. - Kirchlich -Zeitgeschichtliches . .. 478 Book Review. - Literatul' .................... ...... , 489 Eln Prediger m.. nlcbt .nelo IDtidma, £3 lot keln Din!:. daa die Leute lIIehr aJeo d er dj~ Scbafe unterweise, wle bel d.r KU'cbe bebaelt denn dl~ CUI4 lie recllte ObrlRm 1O!!e:: ..10, IOndem Pr' dll'(l;. - .Apowou • .Art. !.t. .nch danebi'tl d... WoeltfD tofhrm, daaa lie die Scba1e nlcht angrellen 1DId mit It tb~ trumpet rive UI IIDC<'mln 1OUIId, falacber Lehre ftrluebren und latun) eln· who ili~U p~ ... hllM'!lf to the battle t fuebm!. - lA,tw. i Ofn'. U , 8. Published for the Ev. Luth. Synod of Missouri, Ohio, and Other States OONOORDU PUBLISHING BOUSE, St. Louis, Mo. ~ ARCHIV:- The Story of the German Bible. 425 drink." "The colored stole is both the badge of pastoral attthority and the symbol of the yoke of righteousness." ~oIdje 2ru~fpriidje finb iuoljI nidjt tedjt liebadjt, geljen jebodj liliet bie tedjte Iutljetif dje Wlitte ljinau~ .13) 2tliet luit modjten in ber niidjften mummer nodj einige @elitiiudje unb @imidjtungen .bet ti.imifdjen S'\:irdje liefptedjcn, bie burdj ntutgifdje ~etuegungen audj in an.bete S'\:irdjen @ingang finben, unb bamit biefe 2lrtifeheilje alifdjfie13et1. -

A Thousand Years of the Bible 19

A THOUSAND YEARS OF THE BIBLE 19. Petrus Comestor, Bible Historíale, translated by Guiart des Moulins. Paris, circa 1375. Ms. 1, vol. 2, fol. 86v: Jeremiah Before Jerusalem in Flames. A THOUSAND YEARS OF THE BIBLE AN EXHIBITION OF MANUSCRIPTS FROM THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM MALIBU AND PRINTED BOOKS FROM THE DEPARTMENT OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS UNIVERSITY RESEARCH LIBRARY, UCLA Malibu Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum University of California 1991 Cover illustration: 12. Gospel Book, Helmarshausen Abbey, Germany, circa 1120-1140. Ms. Ludwig II 3, fol. 51v: Saint Mark Writing his Gospel © January 1991 by The J. Paul Getty Museum and The Regents of the University of California ISBN 0-89236-193-X TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD by John Walsh and Gloria Werner vii BIBLE COLLECTIONS IN LOS ANGELES by John Bidwell 1 THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM: MEDIEVAL AND RENAISSANCE MANUSCRIPTS by Ranee Katzenstein INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION 15 CHECKLIST 35 ILLUSTRATIONS 41 THE DEPARTMENT OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UNIVERSITY RESEARCH LIBRARY, UCLA: THE PRINTED WORD by David S. Zeidberg and James Davis INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION 61 CHECKLIST 77 ILLUSTRATIONS 87 This page intentionally left blank FOREWORD In the years since Henry Huntington acquired his Guten berg Bible, southern California has become a center for study ing the arts of the book. Each of the region's libraries, universities, and museums can boast individual treasures, but when these resources are taken together, the results are remarkable. The extent to which the collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum and UCLÄs research libraries complement each other can be judged in^l Thousand Years of the Bible. -

The-Gutenberg-Museum-Mainz.Pdf

The Gutenberg Museum Mainz --------------------------------------------------------------------- Two original A Guide Gutenberg Bibles and many to the other documents from the dawn of the age of printing Museum ofType and The most beautiful Printing examples from a collection of 3,000 early prints Printing presses and machines in wood and iron Printing for adults and children at the Print Shop, the museum's educational unit Wonderful examples of script from many countries of the world Modern book art and artists' books Covers and illustrations from five centuries Contents The Gutenberg Museum 3 Johannes Gutenberg- the Inventor 5 Early Printing 15 From the Renaissance to the Rococo 19 19th Century 25 20th Century 33 The Art and Craftmanship of the Book Cover 40 Magic Material Paper 44 Books for Children and Young Adults 46 Posters, Job Printing and Ex-Libris 48 Graphics Techniques 51 Script and Printing in Eastern Asia 52 The Development of Notation in Europe and the Middle East 55 History and Objective of the Small Press Archives in Mainz 62 The Gutenberg Museum Print Shop 63 The Gutenberg Society 66 The Gutenberg-Sponsorship Association and Gutenberg-Shop 68 Adresses and Phone Numbers 71 lmpressum The Gutenberg Museum ~) 2001 The Cutcnlx~rg Museum Mainz and the Cutcnbc1g Opposite the cathedral in the heart of the old part ofMainz Spons01ship Association in Germany lies the Gutenberg Museum. It is one of the oldest museums of printing in the world and This guide is published with tbc kind permission of the attracts experts and tourists from all corners of the globe. Philipp von Zahc1n publisher's in Mainz, In r9oo, soo years after Gutenberg's birth, a group of citi with regard to excLrpts of text ;md illustrations zens founded the museum in Mainz.