Tiberius and the Heavenly Twins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resettlement Into Roman Territory Across the Rhine and the Danube Under the Early Empire (To the Marcomannic Wars)*

Eos C 2013 / fasciculus extra ordinem editus electronicus ISSN 0012-7825 RESETTLEMENT INTO ROMAN TERRITORY ACROSS THE RHINE AND THE DANUBE UNDER THE EARLY EMPIRE (TO THE MARCOMANNIC WARS)* By LESZEK MROZEWICZ The purpose of this paper is to investigate the resettling of tribes from across the Rhine and the Danube onto their Roman side as part of the Roman limes policy, an important factor making the frontier easier to defend and one way of treating the population settled in the vicinity of the Empire’s borders. The temporal framework set in the title follows from both the state of preser- vation of sources attesting resettling operations as regards the first two hundred years of the Empire, the turn of the eras and the time of the Marcomannic Wars, and from the stark difference in the nature of those resettlements between the times of the Julio-Claudian emperors on the one hand, and of Marcus Aurelius on the other. Such, too, is the thesis of the article: that the resettlements of the period of the Marcomannic Wars were a sign heralding the resettlements that would come in late antiquity1, forced by peoples pressing against the river line, and eventu- ally taking place completely out of Rome’s control. Under the Julio-Claudian dynasty, on the other hand, the Romans were in total control of the situation and transferring whole tribes into the territory of the Empire was symptomatic of their active border policies. There is one more reason to list, compare and analyse Roman resettlement operations: for the early Empire period, the literature on the subject is very much dominated by studies into individual tribe transfers, and works whose range en- * Originally published in Polish in “Eos” LXXV 1987, fasc. -

A New Perspective on the Early Roman Dictatorship, 501-300 B.C

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. BY Jeffrey A. Easton Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Committee Members Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date defended: April 26, 2010 The Thesis Committee for Jeffrey A. Easton certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. Committee: Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date approved: April 27, 2010 ii Page left intentionally blank. iii ABSTRACT According to sources writing during the late Republic, Roman dictators exercised supreme authority over all other magistrates in the Roman polity for the duration of their term. Modern scholars have followed this traditional paradigm. A close reading of narratives describing early dictatorships and an analysis of ancient epigraphic evidence, however, reveal inconsistencies in the traditional model. The purpose of this thesis is to introduce a new model of the early Roman dictatorship that is based upon a reexamination of the evidence for the nature of dictatorial imperium and the relationship between consuls and dictators in the period 501-300 BC. Originally, dictators functioned as ad hoc magistrates, were equipped with standard consular imperium, and, above all, were intended to supplement consuls. Furthermore, I demonstrate that Sulla’s dictatorship, a new and genuinely absolute form of the office introduced in the 80s BC, inspired subsequent late Republican perceptions of an autocratic dictatorship. -

Rodolfo Lanciani, the Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome, 1897, P

10/29/2010 1 Primus Adventus ad Romam Urbem Aeternam Your First Visit to Rome The Eternal City 2 Accessimus in Urbe AeternA! • Welcome, traveler! Avoiding the travails of the road, you arrived by ship at the port of Ostia; from there, you’ve had a short journey up the Via Ostiensis into Roma herself. What do you see there? 3 Quam pulchra est urbs aeterna! • What is there to see in Rome? • What are some monuments you have heard of? • How old are the buildings in Rome? • How long would it take you to see everything important? 4 Map of Roma 5 The Roman Forum • “According to the Roman legend, Romulus and Tatius, after the mediation of the Sabine women, met on the very spot where the battle had been fought, and made peace and an alliance. The spot, a low, damp, grassy field, exposed to the floods of the river Spinon, took the name of “Comitium” from the verb coire, to assemble. It is possible that, in consequence of the alliance, a road connecting the Sabine and the Roman settlements was made across these swamps; it became afterwards the Sacra Via…. 6 The Roman Forum • “…Tullus Hostilius, the third king, built a stone inclosure on the Comitium, for the meeting of the Senators, named from him Curia Hostilia; then came the state prison built by Ancus Marcius in one of the quarries (the Tullianum). The Tarquin [kings] drained the land, gave the Forum a regular (trapezoidal) shape, divided the space around its borders into building- lots, and sold them to private speculators for shops and houses, the fronts of which were to be lined with porticoes.” --Rodolfo Lanciani, The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome, 1897, p. -

THE MADNESS of the EMPEROR CALIGULA (Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus) by A

THE MADNESS OF THE EMPEROR CALIGULA (Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus) by A. T. SANDISON, B.Sc., M.D. Department of Pathology, the University and Western Infirmaty, Glasgow THROUGHOUT the centuries the name of Caligula has been synonymous with madness and infamy, sadism and perversion. It has been said that Marshal Gilles de Rais, perhaps the most notorious sadist of all time, modelled his behaviour. on that of the evil Caesars described by Suetonius, among whom is numbered Caligula. Of recent years, however, Caligula has acquired his apologists, e.g. Willrich; so also, with more reason, has the Emperor Tiberius, whose reputation has been largely rehabilitated by modern scholarship. Our knowledge of the life of Caligula depends largely on Suetonius, whose work D)e vita Caesarum was not published, until some eighty years after the death of Caligula in A.D. 41. Unfortunately that part ofTacitus's Annals which treated of the reign. of Caligula has been lost. Other ancient sources are Dio Cassius, whose History of Rome was written in the early third century and, to a lesser extent, Josephus, whose Anht itates Judaicac was published in A.D. 93, and Philo Jqdaeus, whose pamphlet Legatio ad- Gaium and In Flaccum may be considered as contemporary writings. It seems probable that all these ancient sour¢es are to some extent prejudiced and highly coloured. Suetonius's Gaius Caligula in De vita Caesarum is full of scabrous and sometimes entertaining stories, on some ofwhich little reliability can be plat-ed. Nevertheless, the outlines of Caligula's life-history are not in doubt, and a usefiul summary is given by Balsdon (i949) in the Oxford-Classical Dictionary. -

Tiberius Nero Caesar (Tiberius) - the Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Volume 3

Tiberius Nero Caesar (Tiberius) - The Lives Of The Twelve Caesars, Volume 3. C. Suetonius Tranquillus Project Gutenberg's Tiberius Nero Caesar (Tiberius), by C. Suetonius Tranquillus This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Tiberius Nero Caesar (Tiberius) The Lives Of The Twelve Caesars, Volume 3. Author: C. Suetonius Tranquillus Release Date: December 13, 2004 [EBook #6388] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TIBERIUS NERO CAESAR *** Produced by Tapio Riikonen and David Widger THE LIVES OF THE TWELVE CAESARS By C. Suetonius Tranquillus; To which are added, HIS LIVES OF THE GRAMMARIANS, RHETORICIANS, AND POETS. The Translation of Alexander Thomson, M.D. revised and corrected by T.Forester, Esq., A.M. Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. TIBERIUS NERO CAESAR. (192) I. The patrician family of the Claudii (for there was a plebeian family of the same name, no way inferior to the other either in power or dignity) came originally from Regilli, a town of the Sabines. They removed thence to Rome soon after the building of the city, with a great body of their dependants, under Titus Tatius, who reigned jointly with Romulus in the kingdom; or, perhaps, what is related upon better authority, under Atta Claudius, the head of the family, who was admitted by the senate into the patrician order six years after the expulsion of the Tarquins. -

Una-Theses-0191.Pdf

RHET ORIO AL COLOR IN THE ANNALS OF ':L1AC ITUS • BOOKS I - VI. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of the University of Minnesota Harold Omer Burgess In Partial ""L1lfillment of the requireme nts for the degree of .·' ·. ~:. Master of Arts, 1913. .... .. ,c Cf ~ cf ~ ( l (CC ~Cc c' I c1 I : I :. :~/: ~ :'c! !\~ :' .'~•,,,•: /•\ c Cl f I I ICC C ! ~ ·. ( •. .·. : . : '. : ( (ff( 11 1 I I 11 II ( ( C f I I I It I I I Cff I f(C I I I I 4 I t -1- Bibliography. Mer ivale;· The Rcmans Under the Empire. Gould; T~ e Tragedy of the Caesars. ~ruttwell;History of Roman Literature. werrero; Characters and Events of Roman History. Jerome;: The Tacitean Tiberius ;· Classical Philology, Vol. VII, o. 3. Fu~rneaux;· Annals of Ta01tus- cc'c ! 1 ' c't !•: •, ,• (fC ff( ( C Cc II C ( CI f CCC It t f(C f (f( f Cf Ct t I -2- 0UTLINE . I. Introduction 1. General statement. II. Body I. Division of subject (a) Difference between real Tiberius and Taci tean Tiberius. (b) Motives of Tacitus in misrepresenting Tiberius (c) Rhetorical methods used. 1. B1nts, innuendos, Sneers. 11- Motives ascrioed for actions. 111- Manipulation of Stress and Reticence. lV- use of the Gossip of the capital. V- Facial Expressions. Vl- Invented Episodes. Vll- Mere assertions. Vlll- Generalizations unsunported bY facts. III. Conclusion~ Concrete example of how Tacitus appl\ ~ : :t',~f': ~qrk · T «/ :"'~~:· , ('rt r ' '' r < ' c •,• • cal color in at tribut ine the death or 'Q-er~n.i(!1Jf3r' ......... -

GIPE-001655-Contents.Pdf

Dhananjayarao Gadgil Libnuy IIm~ mlll~ti 111Im11 ~llllm liD· . GIPE-PUNE-OO 16.5 5 ..~" ~W~"'JU.+fJuvo:.""~~~""VW; __uU'¥o~'W'WQVW.~~¥WM'tI;:J'-:~ BORN'S STANDARD LlBRtJLY. t~ ------------------------' t~ SCHLEGEL'S LECTURES ON MODERN HISTORY. t", IY LAMARTINE'S HISTORY OF THE FRENCH REVO~UTION· OF' 1841. fj " 50. JUIlIUS'S LETTERS, ..itb 1'01<', AJdibOUO, Eony.lDdex, &;C. B Volt. Co, 6&sg~l~~;~s~1~tfj;R~\¥I~Eg~H~.:~~8~\f!~~~:::tTI.~~e~: Comj.lJ.t;te u. , Vola., wiLia !nOel:, ' •. ~fJ; t TAYt..On·S (JEREMY) KOLY LIVING AND DYING. ,,,,,,,,01.1. f QOrrHE'S WORKS . .v"r In. [4·}'au9t." u."big'!niot.," "T0"'f'"lW TURn," ~ ~ ~titl. 'J }.;gJnont:') l'n,nsla:led by ~h88 ttWO\«WiC"" WH.• 14 Goetz von B,n .... ~ .aduncuu," tralHJated by iiI. WAin.x ~(u:'r. It. I $6,'68. 61. ee. 67, 75, & 112, NEANDER'S CHURCH HISTORY. Coretully ,''; l ."vt.cd by the Rzv. A • .I. W. MQl.lU*ON. & full. \HUl ladtx. 1::; CJ~ • NEANDER'S '-lfE OF CHRIST. to1 64, NEANDER'S PLANTING OF CHRISTIANITY, II< ANTIGNOSTlKUS, i i Volt. f.~ i CREG,ORY'$ (DR.) LETTERS ON THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION. «( • 153. JAMES' (G, P. R.) LOUIS XIV. Complet. in i Vola. 1'." .... ". t;-; ~ II< 70, SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS' UTERAflY WOlrKS, with Memoir, II Vol •• PorI. f(; ANDREW rULLER'S PRINCIPAL WORKS. 1'""".U. a; ,B~-:~~~S ANALOGY or RELIGION, AND SERMONS, wilh Nola. ~ t1 MISS BREMER'S WORKS. TransJated hy MAVY Rowrn. 'New Edition, ff'ri.e4. Eq ,\'1.11.1. 1" The ~eif4:rlboUfil" and other THlca.) Post 8yo. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Ancient Greek Architecture

Greek Art in Sicily Greek ancient temples in Sicily Temple plans Doric order 1. Tympanum, 2. Acroterium, 3. Sima 4. Cornice 5. Mutules 7. Freize 8. Triglyph 9. Metope 10. Regula 11. Gutta 12. Taenia 13. Architrave 14. Capital 15. Abacus 16. Echinus 17. Column 18. Fluting 19. Stylobate Ionic order Ionic order: 1 - entablature, 2 - column, 3 - cornice, 4 - frieze, 5 - architrave or epistyle, 6 - capital (composed of abacus and volutes), 7 - shaft, 8 - base, 9 - stylobate, 10 - krepis. Corinthian order Valley of the Temples • The Valle dei Templi is an archaeological site in Agrigento (ancient Greek Akragas), Sicily, southern Italy. It is one of the most outstanding examples of Greater Greece art and architecture, and is one of the main attractions of Sicily as well as a national momument of Italy. The area was included in the UNESCO Heritage Site list in 1997. Much of the excavation and restoration of the temples was due to the efforts of archaeologist Domenico Antonio Lo Faso Pietrasanta (1783– 1863), who was the Duke of Serradifalco from 1809 through 1812. • The Valley includes remains of seven temples, all in Doric style. The temples are: • Temple of Juno, built in the 5th century BC and burnt in 406 BC by the Carthaginians. It was usually used for the celebration of weddings. • Temple of Concordia, whose name comes from a Latin inscription found nearby, and which was also built in the 5th century BC. Turned into a church in the 6th century AD, it is now one of the best preserved in the Valley. -

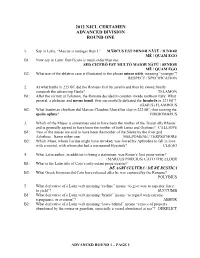

2012 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2012 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Say in Latin, “Marcus is younger than I.” MĀRCUS EST MINOR NĀTŪ / IUNIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B1: Now say in Latin: But Cicero is much older than me. SED CICERŌ EST MULTŌ MAIOR NĀTŪ / SENIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B2: What use of the ablative case is illustrated in the phrase minor nātū, meaning “younger”? RESPECT / SPECIFICATION 2. At what battle in 225 BC did the Romans first by javelin and then by sword finally vanquish the advancing Gauls? TELAMON B1: After the victory at Telamon, the Romans decided to counter-invade northern Italy. What general, a plebeian and novus homō, first successfully defeated the Insubrēs in 223 BC? (GAIUS) FLAMINIUS B2: What Insubrian chieftain did Marcus Claudius Marcellus slay in 222 BC, thus earning the spolia opīma? VIRIDOMARUS 3. Which of the Muses is sometimes said to have been the mother of the Trojan ally Rhesus and is generally agreed to have been the mother of both Linus and Orpheus? CALLIOPE B1: Two of the muses are said to have been the mother of the Sirens by the river god Achelous. Name either one. MELPOMENE / TERPSICHORE B2: Which Muse, whom Tacitus might have invoked, was forced by Aphrodite to fall in love with a mortal, with whom she had a son named Hyacinth? CL(E)IO 4. What Latin author, in addition to being a statesman, was Rome’s first prose writer? (MARCUS PORCIUS) CATO THE ELDER B1: What is the Latin title of Cato’s only extant prose treatise? DĒ AGRĪ CULTŪRĀ / DĒ RĒ RUSTICĀ B2: What Greek historian did Cato have released after he was captured by the Romans? POLYBIUS 5. -

Roman Soldier Germanic Warrior Lindsay Ppowellowell

1st Century AD Roman Soldier VERSUS Germanic Warrior Lindsay Powell © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com 1st Century ad Roman Soldier Germanic Warrior Lindsay PowellPowell © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION 4 THE OPPOSING SIDES 10 Recruitment and motivation t Morale and logistics t Training, doctrine and tactics Leadership and communications t Use of allies and auxiliaries TEUTOBURG PASS 28 Summer AD 9 IDISTAVISO 41 Summer AD 16 THE ANGRIVARIAN WALL 57 Summer AD 16 ANALYSIS 71 Leadership t Mission objectives and strategies t Planning and preparation Tactics, combat doctrine and weapons AFTERMATH 76 BIBLIOGRAPHY 78 INDEX 80 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com Introduction ‘Who would leave Asia, or Africa, or Italia for Germania, with its wild country, its inclement skies, its sullen manners and aspect, unless indeed it were his home?’ (Tacitus, Germania 2). This negative perception of Germania – the modern Netherlands and Germany – lay behind the reluctance of Rome’s great military commanders to tame its immense wilderness. Caius Iulius Caesar famously threw a wooden pontoon bridge across the River Rhine (Rhenus) in just ten days, not once but twice, in 55 and 53 bc. The next Roman general to do so was Marcus Agrippa, in 39/38 bc or 19/18 bc. However, none of these missions was for conquest, but in response to pleas for assistance from an ally of the Romans, the Germanic nation of the Ubii. It was not until the reign of Caesar Augustus that a serious attempt was made to annex the land beyond the wide river and transform it into a province fit for Romans to live in. -

The Temple of Divus Iulus and the Restoration of Legislative

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Classics Faculty Publications Classics Department 2011 The eT mple of Divus Iulus and the Restoration of Legislative Assemblies under Augustus Darryl Phillips Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/classfacpub Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Phillips, Darryl A. "The eT mple of Divus Iulus and the Restoration of Legislative Assemblies under Augustus" in Phoenix. Vol. 65: 3-4 (2011), 371-392 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. THE TEMPLE OF DIVUS IULIUS AND THE RESTORATION OF LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLIES UNDER AUGUSTUS DARRYL A. PHILLIPS I. INTRODUCTION /JLUGUSTUS' ACHIEVEMENT IN BRINGING ORDER TO THE STATE after the turbu- lent years of civil war is celebrated in many and diverse sources. Velleius Pater- culus (2.89.3) records that "force was returned to laws, authority to the courts, and majesty to the Senate, that the power of magistrates was brought back to its old level" (restituta vis legibus, iudiciis auctoritas, senatui maiestas, imperium magistratuum adpristinum redactum modum). Velleius continues on to offer the general summation that the old form of the republic had been reinstated (prisca ilia et antiqua reipublicae forma revocata).^ An aureus from 28 B.C.