Tiberiana 2: Tales of Brave Ulysses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAPRI È...A Place of Dream. (Pdf 2,4

Posizione geografica Geographical position · Geografische Lage · Posición geográfica · Situation géographique Fra i paralleli 40°30’40” e 40°30’48”N. Fra i meridiani 14°11’54” e 14°16’19” Est di Greenwich Superficie Capri: ettari 400 Anacapri: ettari 636 Altezza massima è m. 589 Capri Giro dell’isola … 9 miglia Clima Clima temperato tipicamente mediterraneo con inverno mite e piovoso ed estate asciutta Between parallels Zwischen den Entre los paralelos Entre les paralleles 40°30’40” and 40°30’48” Breitenkreisen 40°30’40” 40°30’40”N 40°30’40” et 40°30’48” N N and meridians und 40°30’48” N Entre los meridianos Entre les méridiens 14°11’54” and 14°16’19” E Zwischen den 14°11’54” y 14°16’19” 14e11‘54” et 14e16’19“ Area Längenkreisen 14°11’54” Este de Greenwich Est de Greenwich Capri: 988 acres und 14°16’19” östl. von Superficie Surface Anacapri: 1572 acres Greenwich Capri: 400 hectáreas; Capri: 400 ha Maximum height Fläche Anacapri: 636 hectáreas Anacapri: 636 ha 1,920 feet Capri: 400 Hektar Altura máxima Hauter maximum Distances in sea miles Anacapri: 636 Hektar 589 m. m. 589 from: Naples 17; Sorrento Gesamtoberfläche Distancias en millas Distances en milles 7,7; Castellammare 13; 1036 Hektar Höchste marinas marins Amalfi 17,5; Salerno 25; Erhebung über den Nápoles 17; Sorrento 7,7; Naples 17; Sorrento 7,7; lschia 16; Positano 11 Meeresspiegel: 589 Castellammare 13; Castellammare 13; Amalfi Distance round the Entfernung der einzelnen Amalfi 17,5; Salerno 25; 17,5 Salerno 25; lschia A Place of Dream island Orte von Capri, in Ischia 16; Positano 11 16; Positano 11 9 miles Seemeilen ausgedrükt: Vuelta a la isla por mar Tour de l’ île par mer Climate Neapel 17, Sorrento 7,7; 9 millas 9 milles Typical moderate Castellammare 13; Amalfi Clima Climat Mediterranean climate 17,5; Salerno 25; lschia templado típicamente Climat tempéré with mild and rainy 16; Positano 11 mediterráneo con typiquement Regione Campania Assessorato al Turismo e ai Beni Culturali winters and dry summers. -

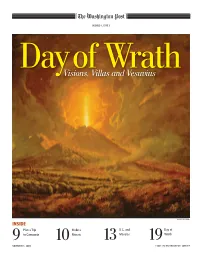

Day of Wrath.Indd

[ABCDE] VOLUME 8, ISSUE 3 Day of Wrath Visions, Villas and Vesuvius HUNTINGTON LIBRARY INSIDE Plan a Trip Make a D.C. and Day of 9 to Campania 10 Mosaic 13 Mosaics 19 Wrath NOVEMBER 5, 2008 © 2008 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 8, ISSUE 3 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program About Day of Wrath Lesson: The influence of ancient Greece on A Sunday Style & Arts review of the National Gallery of Art the Roman Empire and Western civilization exhibit, “Pompeii and the Roman Villa: Art and Culture Around can be seen in its impact on the arts that the Bay of Naples,” and a Travel article, featuring the villas remain in contemporary society. near Vesuvius, are the stimulus for this month’s Post NIE online Level: Low to high guide. This is the first exhibition of Roman antiquities at the Subjects: Social Studies, Art National Gallery. Related Activity: Mathematics, English “The lost-found story of Pompeii, which seemed to have a moral — of confidence destroyed and decadence chastised — appeared ideally devised for the ripe Victorian mind.” But its influence did not stop in 19th-century England. Pompeian influences exist in the Library of Congress, the Senate Appropriations Committee room and around D.C. We provide resources to take a Road Trip (or Metro ride) to some of these places. Although the presence of Vesuvius that destroyed and preserved a way of life is not forgotten, the visitor to the exhibit is taken by the garden of rosemary and laurel, the marble and detailed craftsmanship, the frescos and mosaics. -

Amalfi Coast & Cilento Regions of Campania Campania, Italy

Campania, Italy |Culinary & Cultural Adventure! Amalfi Coast & Cilento Regions of Campania Depart: USA on May 26, 2020 | Return to USA on June 4, 2020 9 Fun Days & 8 Nights of a CULINARY and CULTURAL ADVENTURE $2,995.00 per person . 5-Star Hotel . Mount Vesuvius Winery . Cooking with a Baroness . Beautiful Sightseeing Tours . “Hands-On” Mozzarella Experience . Temples of Paestum (Magna Graecia) . Enjoy the same hotel for entire tour . Beach & Fun in the Sun Time! Explore Campania! Enjoy a culinary and cultural adventure of a lifetime as you visit two of the most spectacular regions of Campania. Savor the glamor & glitz of the Amalfi Coast along with the Cilento region (known as one of Italy’s best kept secrets, and home of the Mediterranean diet). Relish in the “sweet life” of southern Italy and its gracious people on this one-of-a-kind tour. 1 ITALY: CAMPANIA & CILENTO REGION TOUR ITINERARY DAY TO DAY ITINERARY May 27 – June 4, 2020 IMPORTANT: Departure should be scheduled for May 26rd in order to arrive on May 27th. Day 1: Arrival | Naples International Airport DINNER Meet and greet at Naples International Airport. Bus transfer is provided for the group from the airport to Hotel Sole Splendid. Relax, settle in, and enjoy the amenities of the hotel and the beautiful beach. In the evening, meet the group for a welcome dinner. Day 2: Splendors of Positano & Amalfi Experience BREAKFAST LUNCH Breakfast at the hotel. Bus departure for the port of Salerno to the alluring towns of Positano and Amalfi. Then you’ll experience a ferry ride to the chic village of Positano, famous for its glamorous shopping, restaurants, beautiful cliff-side panoramic views, and the magnificent Church of Santa Maria. -

AD Default.Pdf

our tenter de comprendre l'engouement qu'a toujours suscité Capri, perle de la Méditerranée, il faut s'y rendre à bord de l'un des ferries qui, tous les vendredis après-midi, de mai à septembre, quittent Naples, depuis le môle Beverello, en direction de l'île. Accou- dés au bastingage, les hommes bavardent gaiement sur leur téléphone portable der- nier cri avec leurs amis moins chanceux, retenus au travail à Naples, à Rome ou à Milan. Les femmes - de la grande bour- geoisie ou de l'aristocratie italiennes - affi- chent un look qui rappelle celui de la Jackie Kennedy des années 50: pantalon en coton style pêcheur, sandales à talon plat ou espadrilles à semelle de corde et haut pastel. Seules concessions à l'esprit du temps: le sac à main Gucci ou Prada et les lunettes de soleil Versace ou Fendi. Quelques bijoux de corail ou de turquoises soulignent le caractère décidément estival de cette tenue de villégiature. L'engouement des élites pour Capri n'est pas chose nouvelle. Déjà l'empereur Tibère décidait, en l'an 27 de notre ère, d'aban- donner Rome pour venir s'y installer... Dès le tournant du XVIIe siècle, l'île enchanta 1. Le grand salon de la villa Fersen est orné de marbres précieux, colonnes, stucs, et dorures. 2. Les fêtes organisées parle baron Jacques d'Adelsward -Fersen s'achevaient dans la chambre à opium. les «étrangers». D'abord des Allemands, léopard et se rendait à dîner chez ses amis des Français, des Anglais et des Suédois, avec un serpent enroulé au poignet en puis des Russes et enfin des Américains qui guise de bracelet.. -

The Aurea Aetas and Octavianic/Augustan Coinage

OMNI N°8 – 10/2014 Book cover: volto della statua di Augusto Togato, su consessione del Ministero dei beni e delle attivitá culturali e del turismo – Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Roma 1 www.omni.wikimoneda.com OMNI N°8 – 11/2014 OMNI n°8 Director: Cédric LOPEZ, OMNI Numismatic (France) Deputy Director: Carlos ALAJARÍN CASCALES, OMNI Numismatic (Spain) Editorial board: Jean-Albert CHEVILLON, Independent Scientist (France) Eduardo DARGENT CHAMOT, Universidad de San Martín de Porres (Peru) Georges DEPEYROT, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (France) Jean-Marc DOYEN, Laboratoire Halma-Ipel, UMR 8164, Université de Lille 3 (France) Alejandro LASCANO, Independent Scientist (Spain) Serge LE GALL, Independent Scientist (France) Claudio LOVALLO, Tuttonumismatica.com (Italy) David FRANCES VAÑÓ, Independent Scientist (Spain) Ginés GOMARIZ CEREZO, OMNI Numismatic (Spain) Michel LHERMET, Independent Scientist (France) Jean-Louis MIRMAND, Independent Scientist (France) Pere Pau RIPOLLÈS, Universidad de Valencia (Spain) Ramón RODRÍGUEZ PEREZ, Independent Scientist (Spain) Pablo Rueda RODRÍGUEZ-VILa, Independent Scientist (Spain) Scientific Committee: Luis AMELA VALVERDE, Universidad de Barcelona (Spain) Almudena ARIZA ARMADA, New York University (USA/Madrid Center) Ermanno A. ARSLAN, Università Popolare di Milano (Italy) Gilles BRANSBOURG, Universidad de New-York (USA) Pedro CANO, Universidad de Sevilla (Spain) Alberto CANTO GARCÍA, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain) Francisco CEBREIRO ARES, Universidade de Santiago -

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N. Purcell, 1997 Introduction The landscape of central Italy has not been intrinsically stable. The steep slopes of the mountains have been deforested–several times in many cases–with consequent erosion; frane or avalanches remove large tracts of regolith, and doubly obliterate the archaeological record. In the valley-bottoms active streams have deposited and eroded successive layers of fill, sealing and destroying the evidence of settlement in many relatively favored niches. The more extensive lowlands have also seen substantial depositions of alluvial and colluvial material; the coasts have been exposed to erosion, aggradation and occasional tectonic deformation, or–spectacularly in the Bay of Naples– alternating collapse and re-elevation (“bradyseism”) at a staggeringly rapid pace. Earthquakes everywhere have accelerated the rate of change; vulcanicity in Campania has several times transformed substantial tracts of landscape beyond recognition–and reconstruction (thus no attempt is made here to re-create the contours of any of the sometimes very different forerunners of today’s Mt. Vesuvius). To this instability must be added the effect of intensive and continuous intervention by humanity. Episodes of depopulation in the Italian peninsula have arguably been neither prolonged nor pronounced within the timespan of the map and beyond. Even so, over the centuries the settlement pattern has been more than usually mutable, which has tended to obscure or damage the archaeological record. More archaeological evidence has emerged as modern urbanization spreads; but even more has been destroyed. What is available to the historical cartographer varies in quality from area to area in surprising ways. -

Loeb Lucian Vol5.Pdf

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. EDITED BY fT. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. litt.d. tE. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. tW. H. D. ROUSE, f.e.hist.soc. L. A. POST, L.H.D. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., LUCIAN V •^ LUCIAN WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY A. M. HARMON OK YALE UNIVERSITY IN EIGHT VOLUMES V LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MOMLXII f /. ! n ^1 First printed 1936 Reprinted 1955, 1962 Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF LTTCIAN'S WORKS vii PREFATOEY NOTE xi THE PASSING OF PEBEORiNUS (Peregrinus) .... 1 THE RUNAWAYS {FugiUvt) 53 TOXARis, OR FRIENDSHIP (ToxaHs vd amiciHa) . 101 THE DANCE {Saltalio) 209 • LEXiPHANES (Lexiphanes) 291 THE EUNUCH (Eunuchiis) 329 ASTROLOGY {Astrologio) 347 THE MISTAKEN CRITIC {Pseudologista) 371 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE GODS {Deorutti concilhim) . 417 THE TYRANNICIDE (Tyrannicidj,) 443 DISOWNED (Abdicatvs) 475 INDEX 527 —A LIST OF LUCIAN'S WORKS SHOWING THEIR DIVISION INTO VOLUMES IN THIS EDITION Volume I Phalaris I and II—Hippias or the Bath—Dionysus Heracles—Amber or The Swans—The Fly—Nigrinus Demonax—The Hall—My Native Land—Octogenarians— True Story I and II—Slander—The Consonants at Law—The Carousal or The Lapiths. Volume II The Downward Journey or The Tyrant—Zeus Catechized —Zeus Rants—The Dream or The Cock—Prometheus—* Icaromenippus or The Sky-man—Timon or The Misanthrope —Charon or The Inspector—Philosophies for Sale. Volume HI The Dead Come to Life or The Fisherman—The Double Indictment or Trials by Jury—On Sacrifices—The Ignorant Book Collector—The Dream or Lucian's Career—The Parasite —The Lover of Lies—The Judgement of the Goddesses—On Salaried Posts in Great Houses. -

Zur Geschichte Der Vogelkundlichen Forschung in Baden-Württemberg 1. Norman Douglas (1868— 1952)

472 © Ornithologische Gesellschaft Bayern,[Verh. download orn. unter Ges. www.biologiezentrum.at Bayern 22, Heft 3/4, 1976] Verh. orn. Ges. Bayern 22, 1976: 472—483 Zur Geschichte der vogelkundlichen Forschung in Baden-Württemberg 1. Norman Douglas (1868— 1952) Von Rudolf Kuhk In seinem vortrefflichen Werk Die Ornithologen Mitteleuropas hat Ludwig Gebhardt die Vogelkundler aller Grade behandelt, soweit sie in Mitteleuropa beheimatet oder, von anderswoher gekommen, hier ansässig geworden waren. Nicht berücksichtigt sind also diejenigen, die nur als Gäste mit mehr oder weniger langem Aufenthalt im Ge biet sich ornithologisch produktiv betätigt haben. Zu dieser nicht gro ßen Gruppe rechnete man auch Norman Douglas, der schottischer Ab kunft war und einigen Angaben zufolge in Schottland geboren sein soll; als Gymnasiast hielt er sich 6 Jahre lang in Deutschland auf, und 1894 veröffentlichte er in einer englischen zoologischen Zeitschrift einen Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Vogelwelt Badens. Als ich mich mit seinem Lebenslauf befaßte, stellte sich bald heraus, daß er nicht in Schottland, sondern in Österreich geboren ist, also doch zu dem von Gebhardt bearbeiteten Personenkreis gehört. Indes kam diese Er kenntnis für die Aufnahme in das Werk zu spät. Lediglich eine Kurz notiz mit den beiden Haupt-Lebensdaten konnte in den letzten „Er gänzungen während des Druckes“ (Band 3) noch eingefügt werden. Da den Ornithologen Deutschlands von und über Douglas höchstens seine erwähnte Arbeit und nunmehr jene Haupt-Daten bekannt sind, soll hier das Dunkel gelichtet werden, das für uns Vogelkundler über dem Leben und dem — unerwartet reichen — Werk dieses Mannes lag. Freilich sollte ich bei der Beschäftigung mit ihm bald erfahren, daß diese Unkenntnis keineswegs von denen geteilt wird, die im bri tischen schöngeistigen Schrifttum oder in der englischen Literatur über Süditalien Bescheid wissen. -

The Waterway of Hellespont and Bosporus: the Origin of the Names and Early Greek Haplology

The Waterway of Hellespont and Bosporus: the Origin of the Names and Early Greek Haplology Dedicated to Henry and Renee Kahane* DEMETRIUS J. GEORGACAS ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. A few abbreviations are listed: AJA = American Journal of Archaeology. AJP = American Journal of Philology (The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, Md.). BB = Bezzenbergers Beitriige zur Kunde der indogermanischen Sprachen. BNF = Beitriige zur Namenforschung (Heidelberg). OGL = Oorpus Glossariorum Latinorum, ed. G. Goetz. 7 vols. Lipsiae, 1888-1903. Chantraine, Dict. etym. = P. Chantraine, Dictionnaire etymologique de la langue grecque. Histoire des mots. 2 vols: A-K. Paris, 1968, 1970. Eberts RLV = M. Ebert (ed.), Reallexikon der Vorgeschichte. 16 vols. Berlin, 1924-32. EBr = Encyclopaedia Britannica. 30 vols. Chicago, 1970. EEBE = 'E:rccr'YJel~ t:ET:ateeta~ Bv~avnvwv E:rcovowv (Athens). EEC/JE = 'E:rcuJT'YJfhOVtUn ' E:rccrrJel~ C/JtAOaocptufj~ EXOAfj~ EIsl = The Encyclopaedia of Islam (Leiden and London) 1 (1960)-. Frisk, GEJV = H. Frisk, Griechisches etymologisches Worterbuch. 2 vols. Heidelberg, 1954 to 1970. GEL = Liddell-Scott-Jones, A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford, 1925-40. A Supplement, 1968. GaM = Geographi Graeci Minores, ed. C. Miiller. GLM = Geographi Latini Minores, ed. A. Riese. GR = Geographical Review (New York). GZ = Geographische Zeitschrift (Berlin). IF = Indogermanische Forschungen (Berlin). 10 = Inscriptiones Graecae (Berlin). LB = Linguistique Balkanique (Sofia). * A summary of this paper was read at the meeting of the Linguistic Circle of Manitoba and North Dakota on 24 October 1970. My thanks go to Prof. Edmund Berry of the Univ. of Manitoba for reading a draft of the present study and for stylistic and other suggestions, and to the Editor of Names, Dr. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 74-10,982

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. White the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Augustus, Agrippa, the Ara Pacis, and the Coinage of 13 Bc

Acta Ant. Hung. 55, 2015, 61–78 DOI: 10.1556/068.2015.55.1–4.4 GAIUS STERN AUGUSTUS, AGRIPPA, THE ARA PACIS, AND THE COINAGE OF 13 BC Summary: In 13 BC, Augustus returned to Rome from a lengthy tour of the western provinces, just as Agrippa returned from the East. All conditions had been readied to present to the Roman people the estab- lishment of Agrippa as the new partner of Augustus’ labours after a multi-year build up, culminating in the Ara Pacis ceremony at which Agrippa co-presided. However, to those watching the political slogans and headlines of the Roman mint, the Ara Pacis ceremony and Agrippa’s prominent role therein did not bring news, for the coinage of 13 boldly proclaims Agrippa as if he were second princeps by advertizing his enhanced status and by highlighting his accomplishments beyond the level ever provided for any of Augustus’ other colleagues, including his eventual successor, Tiberius (whose own enhancement of pow- ers after AD 4 was modeled upon the precedent of Agrippa). The coinage of 13 BC represents a break from the recent general pattern in that it broke up Augus- tus’ quasi-regal domination of the mint, and it sent out two simultaneous and compatible messages. Firstly, and more specifically, the imagery informed the Roman public as do newspaper headlines today of the elevation of Agrippa as Augustus’ legal equal, showing that Rome was no monarchy. The Roman mint al- ternated between standard issues for certain messages and new images for others, including escalation of the status of Agrippa. -

Studia Varia from the J

OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON ANTIQUITIES, 10 Studia Varia from the J. Paul Getty Museum Volume 2 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 2001 © 2001 The J. Paul Getty Trust Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www. getty. edu Christopher Hudson, Publisher Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief Project staff: Editors: Marion True, Curator of Antiquities, and Mary Louise Hart, Assistant Curator of Antiquities Manuscript Editor: Bénédicte Gilman Production Coordinator: Elizabeth Chapin Kahn Design Coordinator: Kurt Hauser Photographers, photographs provided by the Getty Museum: Ellen Rosenbery and Lou Meluso. Unless otherwise noted, photographs were provided by the owners of the objects and are reproduced by permission of those owners. Typography, photo scans, and layout by Integrated Composition Systems, Inc. Printed by Science Press, Div. of the Mack Printing Group Cover: One of a pair of terra-cotta arulae. Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum 86.AD.598.1. See article by Gina Salapata, pp. 25-50. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Studia varia. p. cm.—-(Occasional papers on antiquities : 10) ISBN 0-89236-634-6: English, German, and Italian. i. Art objects, Classical. 2. Art objects:—California—Malibu. 3. J. Paul Getty Museum. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Series. NK665.S78 1993 709'.3 8^7479493—dc20 93-16382 CIP CONTENTS Coppe ioniche in argento i Pier Giovanni Guzzo Life and Death at the Hands of a Siren 7 Despoina Tsiafakis An Exceptional Pair of Terra-cotta Arulae from South Italy 25 Gina Salapata Images of Alexander the Great in the Getty Museum 51 Janet Burnett Grossman Hellenistisches Gold und ptolemaische Herrscher 79 Michael Pfrommer Two Bronze Portrait Busts of Slave Boys from a Shrine of Cobannus in Gaul 115 John Pollini Technical Investigation of a Painted Romano-Egyptian Sarcophagus from the Fourth Century A.D.