CEDA's Top 10 Speeches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue

The Women’s Review of Books Vol. XXI, No. 1 October 2003 74035 $4.00 I In This Issue I In Zelda Fitzgerald, biographer Sally Cline argues that it is as a visual artist in her own right that Zelda should be remembered—and cer- tainly not as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s crazy wife. Cover story D I What you’ve suspected all along is true, says essayist Laura Zimmerman—there really aren’t any feminist news commentators. p. 5 I “Was it really all ‘Resilience and Courage’?” asks reviewer Rochelle Goldberg Ruthchild of Nehama Tec’s revealing new study of the role of gender during the Nazi Holocaust. But generalization is impossible. As survivor Dina Abramowicz told Tec, “It’s good that God did not test me. I don’t know what I would have done.” p. 9 I No One Will See Me Cry, Zelda (Sayre) Fitzgerald aged around 18 in dance costume in her mother's garden in Mont- Cristina Rivera-Garza’s haunting gomery. From Zelda Fitzgerald. novel set during the Mexican Revolution, focuses not on troop movements but on love, art, and madness, says reviewer Martha Gies. p. 11 Zelda comes into her own by Nancy Gray I Johnnetta B. Cole and Beverly Guy-Sheftall’s Gender Talk is the Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise by Sally Cline. book of the year about gender and New York: Arcade, 2002, 492 pp., $27.95 hardcover. race in the African American com- I munity, says reviewer Michele Faith ne of the most enduring, and writers of her day, the flapper who jumped Wallace. -

Let Her Finish: Gender, Sexism, and Deliberative Participation in Australian Senate Estimates Hearings (2006-2015)

Let Her Finish: Gender, Sexism, and Deliberative Participation In Australian Senate Estimates Hearings (2006-2015) Joanna Richards School of Government and Policy Faculty of Business, Government and Law University of Canberra ABSTRACT In 2016, Australia ranks 54th in the world for representation of women in Parliament, with women accounting for only 29% of the House of Representatives, and 39% of the Senate. This inevitably inspires discussion about women in parliament, quotas, and leadership styles. Given the wealth of research which suggests that equal representation does not necessarily guarantee equal treatment, this study focuses on Authoritative representation. That is, the space in between winning a seat and making a difference where components of communication and interaction affect the authority of a speaker.This study combines a Discourse Analysis of the official Hansard transcripts from the Senate Estimates Committee hearings, selected over a 10 year period between 2006 and 2015, with a linguistic ethnography of the Australian Senate to complement results with context. Results show that although female senators and witnesses are certainly in the room, they do not have the same capacity as their male counterparts. Both the access and effectiveness of women in the Senate is limited; not only are they given proportionally less time to speak, but interruption, gate keeping tactics, and the designation of questions significantly different in nature to those directed at men all work to limit female participation in the political domain. As witnesses, empirical measures showed that female testimony was often undermined by senators. Results also showed that female senators and witnesses occasionally adopted masculine styles of communication in an attempt to increase effectiveness in the Senate. -

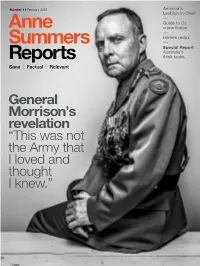

2015 Anne Summers Issue 11 2015

Number 11 February 2015 America’s Lesbian-in-Chief Guide to Oz crime fiction Harlem redux Special Report Australia’s think tanks Sane Factual Relevant General Morrison’s revelation “This was not the Army that I loved and thought I knew.” #11 February 2015 I HOPE YOU ENJOY our first issue for 2015, and our eleventh since we started our digital voyage just over two years ago. We introduce Explore, a new section dealing with ideas, science, social issues and movements, and travel, a topic many of you said, via our readers’ survey late last year, you wanted us to cover. (Read the full results of the survey on page 85.) I am so pleased to be able to welcome to our pages the exceptional mrandmrsamos, the husband-and-wife team of writer Lee Tulloch and photographer Tony Amos, whose piece on the Harlem revival is just a taste of the treats that lie ahead. No ordinary travel writing, I can assure you. Anne Summers We are very proud to publish our first investigative special EDITOR & PUBLISHER report on Australia’s think tanks. Who are they? Who runs them? Who funds them? How accountable are they and how Stephen Clark much influence do they really have? In this landmark piece ART DIRECTOR of reporting, Robert Milliken uncovers how thinks tanks are Foong Ling Kong increasingly setting the agenda for the government. MANAGING EDITOR In other reports, you will meet Merryn Johns, the Australian woman making a splash as a magazine editor Wendy Farley in New York and who happens to be known as America’s Get Anne Summers DESIGNER Lesbian-in-Chief. -

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

International Education Summit 21-23 September 2020

INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION SUMMIT 21-23 SEPTEMBER 2020 In collaboration with ATN INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION SUMMIT WRAP UP INTRODUCTION As Australia’s fourth-largest export industry, and a driver of our economic, social and diplomatic success, International Education is now more important than ever. Now that it is under threat from a perfect storm of local and global headwinds, it is crucial to carefully consider its future. The Australian Technology Network of Universities Mayor Sally Capp, The Hon Ted Baillieu AO, The Hon (ATN) organised the International Education Summit Senator Penny Wong, The Hon Alexander Downer to explore international education’s impact and AC and The Hon Stephen Smith. Minister for Trade, discuss its future. The online Summit brought together Tourism and Investment, The Hon Simon Birmingham university leaders, current and former political MP, opened the Summit, and Minister for Education, the leaders, international students, and representatives Hon Dan Tehan MP closed proceedings. The Summit’s from industries such as tourism, rural and regional final day included broadcasting the signing of our development and small business. All of these groups memorandum of understanding with the Philippines benefit immensely from international education in Commission for Higher Education, hosted by University Australia, be it through students working in hard-to- of Technology Sydney Vice Chancellor and ATN Chair, fill jobs in regional areas, the cultural and intellectual Professor Attila Brungs. diversity international students bring to classrooms and workplaces, or the diplomatic benefit they provide The Summit received a large volume of news coverage as advocates for Australia when back in their home spread across national, international and community countries. -

Australia and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

AUSTRALIA AND THE TREATY ON THE PROHIBITION OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS December 2018 On July 7, 2017, 122 states voted to adopt the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which prohibits states from developing, possessing, or using nuclear weapons.1 While Australia did not participate in the negotiations, there is a strong movement, particularly within the Labor Party, to join the TPNW. As a self-professed “umbrella state,” Australia does not produce or possess nuclear weapons, but it claims to rely on US nuclear weapons for its defense under a policy of so-called “extended nuclear deterrence.” Although the TPNW does not explicitly address the status of nuclear umbrella states like Australia, its prohibitions make it unlawful for a state party to base its national defense on an ally’s nuclear weapons. Therefore, as a state party to the TPNW, Australia would be obliged to renounce its nuclear umbrella. From a legal perspective, Australia can take this step without undermining its collective security agreement with the United States, i.e., the Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty (ANZUS Treaty).2 Joining the TPNW would further Australia’s longstanding commitment to nuclear disarmament, while preserving Australia’s military alliance with the United States. Opinion in Australia is Divided over the TPNW While Australia is not a signatory to the TPNW and did not participate in the treaty’s negotiation, government officials, political parties, and the general public have expressed divergent views about the treaty. The Government of Australia officially opposed the TPNW process. On December 23, 2016, 113 nations voted for UN General Assembly Resolution 71/258 launching negotiations on a “legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons, leading towards their total elimination.”3 Australia was one of 35 nations to vote against this resolution.4 On February 16, 2017, Australia announced its boycott of the treaty negotiations. -

Abandoning the Masculine Domain of Leadership to Identify a New Space for Women's Being, Valuing and Doing

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Abandoning the masculine domain of leadership to identify a new space for women’s being, valuing and doing Diann M. Rodgers-Healey University of Wollongong Rodgers-Healey, Diann M, Abandoning the masculine domain of leadership to identify a new space for women’s being, valuing and doing, PhD thesis, Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong, 2008. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/782 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/782 ABANDONING THE MASCULINE DOMAIN OF LEADERSHIP TO IDENTIFY A NEW SPACE FOR WOMEN’S BEING, VALUING AND DOING A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by DIANN M. RODGERS-HEALEY, B.A. (Sydney Uni), Dip. Ed. (Alex Mackie), M.Ed. (ACU) FACULTY OF EDUCATION JANUARY 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to sincerely thank Professor Stephen Dinham for journeying with me through this study and for his wisdom, proficiency and constructive feedback. I am also extremely grateful to Associate Professor Narottam Bhindi for his unwavering support and guidance and discussion of broader issues of life. My deepest thanks are also extended to my husband, Philip Healey for supporting me in my lengthy quest in every possible way. Sincere thanks to my father Roy Rodgers for his guidance and for ardently encouraging me to be the best I can be. Thank you to my three young sons, Aaron, Benjamin and Matthew whose smiles and cuddles made the tedious juggle so much easier. -

Outstanding 50 LGBTI Leaders

2018 Outstanding 50 LGBTI Leaders In 2016, Deloitte released Australia’s first list of 50 LGBTI Executives, with the purpose of providing visible business role models to LGBTI Australians of all ages. This year, Deloitte is collaborating with Google to celebrate our Outstanding 50 LGBTI Leaders of 2018. Together, we are extremely proud to be recognising the many role models in business, beyond traditional large corporate organisations. We have taken an inclusive approach to include remarkable leaders from the public sector, government and small to medium-sized businesses alongside those in traditional corporate roles. For more on our Outstanding 50 LGBTI leaders of 2018 please visit www.deloitte.com/au/out50 2018 #out50 03 04 Message from Cindy Hook 08 Feyi Akindoyeni 46 Virginia Lovett 11 Dean Allright 49 Denise Lucero 06 Message from Jason Pellegrino 14 Andrew Barr MLA 50 Graeme Mason 15 Simone Bartley 51 Matthew McCarron 08 Profiles and interviews 16 Mark Baxter 52 Jennifer Morris 20 Nicole Brennan 53 Jude Munro AO 84 Our alumni 21 Councillor Tony Briffa JP 54 Rachel Nicolson 24 David Brine 55 Steve Odell 89 Diversity and inclusion 25 John Caldwell 56 Lisa Paul AO PSM 27 Magali De Castro 57 Luke Pellegrini 30 Emma Dunch 61 Neil Pharaoh 31 Cathy Eccles 62 Janet Rice 32 Luci Ellis 63 Anthony Schembri 33 Tiziano Galipo 64 Tracy Smart 34 Mark Gay 65 Dean Smith 35 Alasdair Godfrey 66 Jarther Taylor 36 Dr Cassandra Goldie 67 Michael Tennant 37 Matthew Groskorth 68 Amy Tildesley 39 Manda Hatter 69 Sam Turner 40 Jane Hill 74 Tea Uglow 41 Dawn Hough 75 Louis Vega 42 Steve Jacques 76 Tess Walsh 43 Leigh Johns OAM 79 Benjamin Wash 44 David Jones 80 Lisa Watts Contents 45 Jason Laufer 83 Penny Wong 04 2018 #out50 2018 #out50 05 Message from Cindy Hook, Chief involvement in bringing this next list of Executive Officer, Deloitte Australia: One of dynamic LGBTI Leaders into the public eye. -

Genders at Work: Exploring the Role of Workplace Equality in Preventing Men's Violence Against Women

Genders at Work: Exploring the role of workplace equality in preventing men’s violence against women Scott Holmes and Michael Flood Genders at Work: Exploring the role of workplace equality in preventing men’s violence against women 1 White Ribbon is the world’s largest movement of men and boys working to end men’s violence against women and girls, promote gender equity, healthy relationships and a new vision of masculinity. White Ribbon Australia, as part of this global movement, aims to create an Australian society in which all women can live in safety, free from violence and abuse. We are Australia’s only national, male-led violence prevention organisation. We work to examine the root causes of gender-based violence, challenge behaviours and create a cultural shift that leads us to a future without men’s violence against women. Through education, awareness-raising, preventative programs, partnerships and creative campaigns, we are highlighting the positive role men play in preventing men’s violence against women and inspiring them to be part of this social change. The Research and Policy Group provides expert advice, scholarship and general information on furthering prevention efforts in relation to the: • White Ribbon Research Series – Preventing Men’s Violence Against Women • White Ribbon Factsheets Series • Other White Ribbon resources and publications as required. The White Ribbon Policy Research Series is directed by an expert reference group comprising academic, policy and service experts. At least two reports will be published each year and available from the White Ribbon website at www.whiteribbon.org.au Title: Genders at Work: Exploring the role of workplace equality in preventing men’s violence against women. -

For Personal Use Only Use Personal For

27 November 2007 The Manager Company Announcements Office Australian Securities Exchange Dear Sir, PRESENTATION TO BE GIVEN AT INVESTOR BRIEFING - SYDNEY Following is a presentation that is to be given at an investor briefing on 27 November 2007. Yours faithfully, L J KENYON COMPANY SECRETARY Enc For personal use only Wesfarmers Limited, 11th Floor, “Wesfarmers House”, 40 The Esplanade, Perth, Western Australia, 6000 GPO Box M978, Perth, Western Australia 6843. Telephone: (08) 9327 4211. Facsimile: (08) 9327 4290 www.wesfarmers.com.au Investor Briefing 27 November 2007 For personal use only InterContinental Hotel, Sydney Richard Goyder Managing Director, Wesfarmers Limited For personal use only Agenda 8:30 Coles Update 9:30 Home Improvement & Office Supplies 10:10 Morning Tea 10:30 Insurance 11:00 Chemicals & Fertilisers 11:25 Coal 11:55 Lunch 12:30 Industrial & Safety 12:55 Energy 1:20 Q&A For personal use only 1:50 Other Business / Capital Management 3 Management Team Managing Director & CEO Richard Goyder Finance Director Gene Tilbrook Business Integration Director Keith Gordon Divisional Managing Directors Home Improvement & Office Supplies John Gillam Insurance Rob Scott Chemicals & Fertilisers Ian Hansen Coal Stewart Butel Industrial & Safety Terry Bowen/Olivier Chretien Energy Tim Bult Food, Liquor & Convenience TBA For personal use only Target Launa Inman Kmart Larry Davis 4 Richard Goyder Managing Director, Wesfarmers Limited For personal use only The Coles Transaction – Recent Milestones RECENT MILESTONES 7 November 9 November -

The Roots and Development of Jewish Feminism in the United States, 1972-Present: a Path Toward Uncertain Equality

Aquila - The FGCU Student Research Journal The Roots and Development of Jewish Feminism in the United States, 1972-Present: A Path Toward Uncertain Equality Jessica Evers Division of Social & Behavioral Sciences, College of Arts & Sciences Faculty mentor: Scott Rohrer, Ph.D., Division of Social & Behavioral Sciences, College of Arts & Sciences ABSTRACT This research project involves discovering the pathway to equality for Jewish women, specifically in Reform Judaism. The goal is to show that the ordination of the first woman rabbi in the United States initiated Jewish feminism, and while this raised awareness, full-equality for Jewish women currently remains unachieved. This has been done by examining such events at the ordination process of Sally Priesand, reviewing the scholarship of Jewish women throughout the waves of Jewish feminism, and examining the perspectives of current Reform rabbis (one woman and one man). Upon the examination of these events and perspectives, it becomes clear that the full-equality of women is a continual struggle within all branches of American Judaism. This research highlights the importance of bringing to light an issue in the religion of Judaism that remains unnoticed, either purposefully or unintentionally by many, inside and outside of the religion. Key Words: Jewish Feminism, Reform Judaism, American Jewish History INTRODUCTION “I am a feminist. That is, I believe that being a woman or a in the 1990s and up to the present. The great accomplishments man is an intricate blend of biological predispositions and of Jewish women are provided here, however, as the evidence social constructions that varies greatly according to time and illustrates, the path towards total equality is still unachieved. -

Phd Thesis Jayne Glover FINAL SUBMISSION

“A COMPLEX AND DELICATE WEB”: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF SELECTED SPECULATIVE NOVELS BY MARGARET ATWOOD, URSULA K. LE GUIN, DORIS LESSING AND MARGE PIERCY Thesis Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Rhodes University By Jayne Ashleigh Glover December 2007 Abstract This thesis examines selected speculative novels by Margaret Atwood, Ursula K. Le Guin, Doris Lessing and Marge Piercy. It argues that a specifiable ecological ethic can be traced in their work – an ethic which is explored by them through the tensions between utopian and dystopian discourses. The first part of the thesis begins by theorising the concept of an ecological ethic of respect for the Other through current ecological philosophies, such as those developed by Val Plumwood. Thereafter, it contextualises the novels within the broader field of science fiction, and speculative fiction in particular, arguing that the shift from a critical utopian to a critical dystopian style evinces their changing treatment of this ecological ethic within their work. The remainder of the thesis is divided into two parts, each providing close readings of chosen novels in the light of this argument. Part Two provides a reading of Le Guin’s early Hainish novels, The Left Hand of Darkness , The Word for World is Forest and The Dispossessed , followed by an examination of Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time , Lessing’s The Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five , and Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale . The third, and final, part of the thesis consists of individual chapters analysing the later speculative novels of each author.