Complete Music for Piano Solo Christopher Devine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Des Pas Sur La Neige

19TH CENTURY MUSIC Mystères limpides: Time and Transformation in Debussy’s Des pas sur la neige Debussy est mystérieux, mais il est clair. —Vladimir Jankélévitch STEVEN RINGS Introduction: Secrets and Mysteries sive religious orders). Mysteries, by contrast, are fundamentally unknowable: they are mys- Vladimir Jankélévitch begins his 1949 mono- teries for all, and for all time. Death is the graph Debussy et le mystère by drawing a dis- ultimate mystery, its essence inaccessible to tinction between the secret and the mystery. the living. Jankélévitch proposes other myster- Secrets, per Jankélévitch, are knowable, but ies as well, some of them idiosyncratic: the they are known only to some. For those not “in mysteries of destiny, anguish, pleasure, God, on the secret,” the barrier to knowledge can love, space, innocence, and—in various forms— take many forms: a secret might be enclosed in time. (The latter will be of particular interest a riddle or a puzzle; it might be hidden by acts in this article.) Unlike the exclusionary secret, of dissembling; or it may be accessible only to the mystery, shared and experienced by all of privileged initiates (Jankélévitch cites exclu- humanity, is an agent of “sympathie fraternelle et . commune humilité.”1 An abbreviated version of this article was presented as part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison music collo- 1Vladimir Jankélévitch, Debussy et le mystère (Neuchâtel: quium series in November 2007. I am grateful for the Baconnière, 1949), pp. 9–12 (quote, p. 10). See also his later comments I received on that occasion from students and revision and expansion of the book, Debussy et le mystère faculty. -

Download Booklet

552127-28bk VBO Debussy 10/2/06 8:40 PM Page 8 CD1 1 Nocturnes II. Fêtes . .. 6:56 2 String Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 10 I. Animé et très décidé . 6:11 3 Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune . 10:29 4 Estampes III. Jardins sous la pluie . 3:43 5 Cello Sonata in D minor I. Prologue . 4:25 6 Suite bergamasque III. Clair de lune . 4:26 7 Violin Sonata in G minor II. Intermède: fantastique et léger . 4:17 8 24 Préludes No. 8. La fille aux cheveux de lin . 2:14 9 La Mer II. Jeux de vagues . 7:29 0 Pelléas et Melisande Act III Scene 1 . 14:22 ! 24 Préludes No. 12. Minstrels . 2:05 @ Rapsodie arabe for Alto Saxophone and Orchestra . 10:50 Total Timing . 78:00 CD2 1 Images II. Iberia . 21:43 2 24 Préludes No. 10. La cathédrale engloutie . 5:47 3 Marche écossaise sur un thème populaire . 6:10 4 Images I I. Reflets dans l’eau . 5:15 5 Rêverie . 3:50 6 L’isle joyeuse . 5:29 7 La Mer I. De l’aube à midi sur la mer . 9:18 8 La plus que lente . 4:44 9 Danse sacrée et danse profane II. Danse profane . 5:16 0 Two Arabesques Arabesque No. 1 . 5:05 ! Children’s Corner VI. Golliwogg’s Cake-walk . 3:09 Total Timing . 76:17 FOR FULL LIST OF DEBUSSY RECORDINGS WITH ARTIST DETAILS AND FOR A GLOSSARY OF MUSICAL TERMS PLEASE GO TO WWW.NAXOS.COM 552127-28bk VBO Debussy 10/2/06 8:40 PM Page 2 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918) Children’s Corner VI. -

Debussy Préludes

Debussy Préludes Books I & II RALPH VOTAPEK ~ Debussy 24 Préludes Préludes, Book I (1909-1910) 37:13 1 I. Danseuses de Delphes (Lent et grave) 2:59 2 II. Voiles (Modéré) 3:09 3 III. Le vent dans la plaine (Animé) 2:07 4 IV. Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir (Modéré) 3:10 5 V. Les collines d’Anacapri (Très modéré) 2:57 6 VI. Des pas sur la neige (Triste it lent) 3:47 7 VII. Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest (Animé et tumultueux) 3:23 8 VIII. La fille aux cheveux de lin (Très calme et doucement expressif) 2:29 9 IX. La sérénade interrompue (Modérément animé) 2:28 10 X. La cathédrale engloutie (Profondément calme) 5:54 11 XI. La danse de Puck (Capricieux et léger) 2:40 12 XII. Minstrels (Modéré) 2:10 Préludes, Book II (1912-1913) 36:04 13 I. Brouillards (Modéré) 2:38 14 II. Feuilles mortes (Lent et mélancolique) 2:55 15 III. La Puerta del Vino (Mouvement de Habanera) 3:19 16 IV. Les Fées sont d’exquises danseuses (Rapide et léger) 2:56 17 V. Bruyères (Calme) 2:42 18 VI. Général Lavine — eccentric (Dans le style et le mouvement d’un Cakewalk) 2:28 19 VII. La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune (Lent) 3:59 20 VIII. Ondine (Scherzando) 3:08 21 IX. Hommage à Samuel Pickwick, Esq., P.P.M.P.C. (Grave) 2:25 22 X. Canope (Très calme et doucement triste) 2:53 23 XI. -

1J131J Alexander Boggs Ryan,, Jr., B

omit THE PIANO STYLE OF CLAUDE DEBUSSY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC by 1J131J Alexander Boggs Ryan,, Jr., B. M. Longview, Texas June, 1951 19139 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . , . iv Chapter I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PIANO AS AN INFLUENCE ON STYLE . , . , . , . , . , . ., , , 1 II. DEBUSSY'S GENERAL MUSICAL STYLE . IS Melody Harmony Non--Harmonic Tones Rhythm III. INFLUENCES ON DEBUSSY'S PIANO WORKS . 56 APPENDIX (CHRONOLOGICAL LIST 0F DEBUSSY'S COMPLETE WORKS FOR PIANO) . , , 9 9 0 , 0 , 9 , , 9 ,9 71 BIBLIOGRAPHY *0 * * 0* '. * 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 .9 76 111 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Range of the piano . 2 2. Range of Beethoven Sonata 10, No.*. 3 . 9 3. Range of Beethoven Sonata .2. 111 . , . 9 4. Beethoven PR. 110, first movement, mm, 25-27 . 10 5. Chopin Nocturne in D Flat,._. 27,, No. 2 . 11 6. Field Nocturne No. 5 in B FlatMjodr . #.. 12 7. Chopin Nocturne,-Pp. 32, No. 2 . 13 8. Chopin Andante Spianato,,O . 22, mm. 41-42 . 13 9. An example of "thick technique" as found in the Chopin Fantaisie in F minor, 2. 49, mm. 99-101 -0 --9 -- 0 - 0 - .0 .. 0 . 15 10. Debussy Clair de lune, mm. 1-4. 23 11. Chopin Berceuse, OR. 51, mm. 1-4 . 24 12., Debussy La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune, mm. 32-34 . 25 13, Wagner Tristan und Isolde, Prelude to Act I, . -

Liner Notes (PDF)

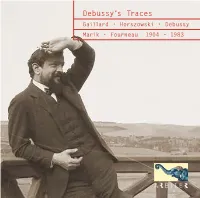

Debussy’s Traces Gaillard • Horszowski • Debussy Marik • Fourneau 1904 – 1983 Debussy’s Traces: Marius François Gaillard, CD II: Marik, Ranck, Horszowski, Garden, Debussy, Fourneau 1. Preludes, Book I: La Cathédrale engloutie 4:55 2. Preludes, Book I: Minstrels 1:57 CD I: 3. Preludes, Book II: La puerta del Vino 3:10 Marius-François Gaillard: 4. Preludes, Book II: Général Lavine 2:13 1. Valse Romantique 3:30 5. Preludes, Book II: Ondine 3:03 2. Arabesque no. 1 3:00 6. Preludes, Book II Homage à S. Pickwick, Esq. 2:39 3. Arabesque no. 2 2:34 7. Estampes: Pagodes 3:56 4. Ballade 5:20 8. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 4:49 5. Mazurka 2:52 Irén Marik: 6. Suite Bergamasque: Prélude 3:31 9. Preludes, Book I: Des pas sur la neige 3:10 7. Suite Bergamasque: Menuet 4:53 10. Preludes, Book II: Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses 8. Suite Bergamasque: Clair de lune 4:07 3:03 9. Pour le Piano: Prélude 3:47 Mieczysław Horszowski: Childrens Corner Suite: 10. Pour le Piano: Sarabande 5:08 11. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:48 11. Pour le Piano: Toccata 3:53 12. Jimbo’s lullaby 3:16 12. Masques 5:15 13 Serenade of the Doll 2:52 13. Estampes: Pagodes 3:49 14. The snow is dancing 3:01 14. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 3:53 15. The little Shepherd 2:16 15. Estampes: Jardins sous la pluie 3:27 16. Golliwog’s Cake walk 3:07 16. Images, Book I: Reflets dans l’eau 4:01 Mary Garden & Claude Debussy: Ariettes oubliées: 17. -

HOLLOWAY/DEBUSSY EN BLANC ET NOIR Thursday, March 11, Marks the World Premiere of an Orchestration by Robin Holloway of Claude Debussy’S En Blanc Et Noir

March 2004 TILSON THOMAS LEADS SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY IN PREMIERE OF HOLLOWAY/DEBUSSY EN BLANC ET NOIR Thursday, March 11, marks the world premiere of an orchestration by Robin Holloway of Claude Debussy’s En blanc et noir. Michael Tilson Thomas leads the San Francisco Symphony at Davies Symphony Hall; the program is repeated on March 12 and 13. En blanc et noir will be performed by the San Francisco Symphony on tour in Kansas City (3/16), Cleveland (3/18), New York (3/23 at Carnegie Hall), Philadelphia (3/24), and Newark (3/26). loyal and persuasive The San Francisco Symphony has consistently championed Holloway’s advocates music. In addition to commissioning En blanc et noir, the ensemble has commissioned and premiered Holloway’s Clarissa Sequence (1998), and given the American premieres of his Viola Concerto and Third Concerto for Orchestra. En blanc et noir, originally composed for piano duo in 1915, is a product of Debussy’s late period, marked by an austere beauty that stands in contrast to the lushness of better-known, earlier works such as Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, La Mer, and the Nocturnes. In orchestrating En blanc et noir, Holloway hopes to bring this seldom performed three-movement work to a wider audience. black and white, As program annotator Michael Steinberg points out, Holloway is in color acutely aware of the irony of coloring a work whose title specifi- cally calls attention to the black-and-whiteness of the piano key- board. Early in 1916, Debussy wrote to his friend Robert Godet: “These pieces draw their color, their emotion, simply from the piano, like the ‘grays’ of Velasquez, if I may so suggest?” Holloway conceives of his orchestration as an “opening out” of the music’s physical resonance, almost as though this were the freeing of a piece that has yearned to be an orchestral work all along. -

24. Debussy Pour Le Piano: Sarabande (For Unit 3: Developing Musical Understanding)

24. Debussy Pour le piano: Sarabande (For Unit 3: Developing Musical Understanding) Introduction and Performance circumstances Debussy probably decided to compose a Sarabande partly because he knew Erik Satie’s three sarabandes of 1887, with their similarly sensuous harmony. There are no grounds for referring to Debussy’s Sarabande as ‘impressionist’, even though the piece is very similar in date to his Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. The term ‘neoclassical’ may be more suitable, although we do not hear the post-World War I type of ‘wrong-note’ neoclassicism of, for example, Stravinsky’s Pulcinella. In public performance Debussy’s Sarabande is most likely to be heard as part of a piano recital, along with the two other movements which flank it (Prélude and Toccata) from Pour le piano. Incidentally the suite was published in 1901, but the Sarabande (in a slightly different version to the one we know) dates back to 1894. Performing Forces and their Handling Sarabande, for solo piano, does not depend for its effect on any virtuosity or display. Marguerite Long, a pupil of Debussy, noted that the composer ‘himself played [the piece] as no one [else] could ever have done, with those marvellous successions of chords sustained by his intense legato’. A wide range is involved, from (several) very low C sharps to E just over five octaves higher; there are no extremely high notes. Some left-hand chords extend to well over an octave and have to be spread. Texture The texture is almost entirely homophonic, with much parallelism, and is often extremely sonorous on account of the many chords with six or more notes. -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

Choral & Classroom

2020–2021 CHORAL & CLASSROOM MORE TO EXPLORE DIGITAL AND ONLINE CHORAL RESOURCES ENHANCE YOUR REVIEW Watch Score & Sound videos Stream or download View or download full to see the music while the full performance PDFs for recording plays. recordings. each voicing. ENHANCE YOUR PRACTICE Use the practice tools and repertoire in SmartMusic to help singers grow and develop. ENHANCE YOUR PERFORMANCE Staging videos for select titles SoundTrax accompaniments PianoTrax accompaniments are are available online. are available online. available individually online. Visit alfred.com/newchoral 2 WELCOME TABLE OF CONTENTS Alfred Choral Designs General Concert & Contest ...........................6 Spirituals .................................................8 Masterworks ............................................9 Dear Music Educator, Folk Songs & World Music .......................... 10 Holiday / Seasonal ....................................11 This is a true story. It was a few decades ago when I first fell in love with Alfred Alfred Pop Series Music’s choral promotion. For real. I noticed the colorful catalog stacked on my Holiday Pop .............................................13 high school music teacher’s inbox and my eyes lit up. Mr. Paine (a great mentor) Current Pop .............................................14 must have sensed my delight, because he offered to loan it out over the weekend. Classic Pop ..............................................14 I was thrilled. I could not wait to get that plastic cassette tape home to my shoebox Contemporary -

MUSIC LIST Email: Info@Partytimetow Nsville.Com.Au

Party Time Page: 1 of 73 Issue: 1 Date: Dec 2019 JUKEBOX Phone: 07 4728 5500 COMPLETE MUSIC LIST Email: info@partytimetow nsville.com.au 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 100 PERCENT PURE LOVE by Crystal Waters 1000 STARS by Natalie Bassingthwaighte {Karaoke} 11 MINUTES by Yungblud - Halsey 1979 by Good Charlotte {Karaoke} 1999 by Prince {Karaoke} 19TH NERVIOUS BREAKDOWN by The Rolling Stones 2 4 6 8 MOTORWAY by The Tom Robinson Band 2 TIMES by Ann Lee 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 21 - GUNS by Greenday {Karaoke} 21 QUESTIONS by 50 Cent 22 by Lilly Allen {Karaoke} 24K MAGIC by Bruno Mars 3 by Britney Spears {Karaoke} 3 WORDS by Cheryl Cole {Karaoke} 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 EVER by The Veronicas {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 4 MINUTES by Madonna And Justin 40 MILES OF ROAD by Duane Eddy 409 by The Beach Boys 48 CRASH by Suzi Quatro 5 6 7 8 by Steps {Karaoke} 500 MILES by The Proclaimers {Karaoke} 60 MILES AN HOURS by New Order 65 ROSES by Wolverines 7 DAYS by Craig David {Karaoke} 7 MINUTES by Dean Lewis {Karaoke} 7 RINGS by Ariana Grande {Karaoke} 7 THINGS by Miley Cyrus {Karaoke} 7 YEARS by Lukas Graham {Karaoke} 8 MILE by Eminem 867-5309 JENNY by Tommy Tutone {Karaoke} 99 LUFTBALLOONS by Nena 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A B C by Jackson 5 A B C BOOGIE by Bill Haley And The Comets A BEAT FOR YOU by Pseudo Echo A BETTER WOMAN by Beccy Cole A BIG HUNK O'LOVE by Elvis A BUSHMAN CAN'T SURVIVE by Tania Kernaghan A DAY IN THE LIFE by The Beatles A FOOL SUCH AS I by Elvis A GOOD MAN by Emerson Drive A HANDFUL -

2017 Preview Notes • Week Four • Persons Auditorium

2017 Preview Notes • Week Four • Persons Auditorium Saturday, August 5 at 8:00pm En blanc et noir (1915) Claude Debussy Born August 22, 1862 • Died March 25, 1918 Duration: approx. 15 minutes • Marlboro Premiere Denounced by Saint-Saëns as the aural equivalent of Cubist artwork, this piano duet indeed renders familiar subjects in unexpected and fragmented ways. Each movement is dedicated to a different person and paired with an epigraph, and that the richness of the written music, accompanying texts, and piano keys themselves—all black and white—contribute to the many colors of the piece is one example of Debussy’s wit. The first movement, a reimagined waltz, is dedicated to Serge Koussevitzky, who is remembered as a great champion of contemporary music. The second movement’s suggestion of distant bugle calls laced with quotations from the hymn “Ein Feste Burg ist unser Gott” is a haunting homage to Debussy’s friend Jacques Charlot, who perished in WWI. The work concludes with a rippling scherzando dedicated to Igor Stravinsky. Participants: Xiaohui Yang, piano; Cynthia Raim, piano Voices of Angels (1996) Brett Dean, in-residence 2017 Born October 23, 1961 Duration: approx. 25 minutes • Marlboro Premiere Brett Dean is no stranger to working with great literary texts, having just premiered his second opera, Hamlet, this summer at Glyndebourne. Like the Debussy, this piece is prefaced by an epigraph. Dean quotes the first of Rilke’s ten Duino Elegies: “Angels (it’s said) are often unable to tell whether they move/amongst the living or the dead. An eternal current/hurtles all ages through both realms for ever, and drowns out their voices in both.” As the elegy questions the conventional distinctions between beauty and terror, life and the afterlife, myth and reality, so does Dean’s composition introduce a range of seemingly contradictory perspectives. -

Claude Debussy Orchestral Works Dirk Altmann · Daniel Gauthier Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart Des SWR · Heinz Holliger 02 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862 – 1918) 03

Claude Debussy Orchestral Works Dirk Altmann · Daniel Gauthier Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart des SWR · Heinz Holliger 02 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862 – 1918) 03 1 Première Rapsodie pour orchestre 7 Prélude à L’après-midi d’un faune [11:35] Diese wesensmäßige Fertigkeit hatte schon in den Chemie“, an der er sich selbst immer neu ergötzen avec clarinette principale [08:15] flûte solo: Tatjana Ruhland frühen Neunzigern die Bedenken des Dichters konnte, und die aus sich selbst erwachsenden For- Stéphane Mallarmé zerstreut, der zunächst von men in Regelwerke zu zwängen, sich im Geflecht Images pour orchestre 8 Rapsodie pour Debussys Ansinnen, die Ekloge vom Après-midi des Gefundenen, bereits „Gehabten“ zu verhed- Deutsch 2 Rondes de Printemps [08:29] orchestre et saxophone [09:45] d’un faune mit Musik zu umgeben, nicht begeis- dern. Vielleicht wurde daher auch nur das Prélude 3 Gigues [08:38] tert war. Er fürchtete eine bloße „Verdopplung“ zum „Faun“ vollendet, während das Interlude und Iberia [19:48] TOTAL TIME [67:04] seiner musikalisch-erotischen Alexandriner, sah die abschließende Paraphrase nie über die Idee 4 I. Par les rues et par les chemins [07:09] sich aber, kaum dass er das Resultat zu hören be- hinausgelangten. Es war schon alles gesagt. 5 II. Les parfums de la nuit [08:10] 1 Dirk Altmann Klarinette | clarinet kam, ebenso bezwungen wie die Besucher der 6 III. Le matin d'un jour de fête [04:28] 8 Daniel Gauthier Saxophon | saxophone Société Nationale, die am 22. Dezember 1894 die Wer weiß, ob nicht aus just diesem Grunde auch Uraufführung des Prélude „zum Nachmittag eines die Rapsodie arabe im Sande verlief, die sich der Fauns“ miterleben durften.