Claude Debussy in 2018: a Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music%2034.Syllabus

Music 34, Detailed Syllabus INTRODUCTION—January 24 (M) “Half-step over-saturation”—Richard Strauss Music: Salome (scene 1), Morgan 9 Additional reading: Richard Taruskin, The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. 4 (henceforth RT), (see Reader) 36-48 Musical vocabulary: Tristan progression, augmented chords, 9th chords, semitonal expansion/contraction, master array Recommended listening: more of Salome Recommended reading: Derrick Puffett, Richard Strauss Salome. Cambridge Opera Handbooks (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989) No sections in first week UNIT 1—Jan. 26 (W); Jan. 31 (M) “Half-steplessness”—Debussy Music: Estampes, No. 2 (La Soiré dans Grenade), Morgan 1; “Nuages” from Three Nocturnes (Anthology), “Voiles” from Preludes I (Anthology) Reading: RT 69-83 Musical vocabulary: whole-tone scales, pentatonic scales, parallelism, whole-tone chord, pentatonic chords, center of gravity/symmetry Recommended listening: Three Noctures SECTIONS start UNIT 2—Feb. 2 (W); Feb. 7 (M) “Invariance”—Skryabin Music: Prelude, Op. 35, No. 3; Etude, Op. 56, No. 4, Prelude Op. 74, No. 3, Morgan 21-25. Reading: RT 197-227 Vocabulary: French6; altered chords; Skryabin6; tritone link; “Ecstasy chord,” “Mystic chord”, octatonicism (I) Recommended reading: Taruskin, “Scriabin and the Superhuman,” in Defining Russia Musically: Historical and Hermeneutical Essays (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 308-359 Recommended listening: Poème d’extase; Alexander Krein, Sonata for Piano UNIT 3—Feb. 9 (W); Feb. 14 (M) “Grundgestalt”—Schoenberg I Music: Opus 16, No. 1, No. 5, Morgan 30-45. Reading: RT 321-337, 341-343; Simms: The Atonal Music of Arnold Schoenberg 1908-1923 (excerpt) Vocabulary: atonal triads, set theory, Grundgestalt, “Aschbeg” set, organicism, Klangfarben melodie Recommended reading: Móricz, “Anxiety, Abstraction, and Schoenberg’s Gestures of Fear,” in Essays in Honor of László Somfai on His 70th Birthday: Studies in the Sources and the Interpretation of Music, ed. -

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

Liner Notes (PDF)

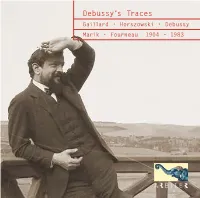

Debussy’s Traces Gaillard • Horszowski • Debussy Marik • Fourneau 1904 – 1983 Debussy’s Traces: Marius François Gaillard, CD II: Marik, Ranck, Horszowski, Garden, Debussy, Fourneau 1. Preludes, Book I: La Cathédrale engloutie 4:55 2. Preludes, Book I: Minstrels 1:57 CD I: 3. Preludes, Book II: La puerta del Vino 3:10 Marius-François Gaillard: 4. Preludes, Book II: Général Lavine 2:13 1. Valse Romantique 3:30 5. Preludes, Book II: Ondine 3:03 2. Arabesque no. 1 3:00 6. Preludes, Book II Homage à S. Pickwick, Esq. 2:39 3. Arabesque no. 2 2:34 7. Estampes: Pagodes 3:56 4. Ballade 5:20 8. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 4:49 5. Mazurka 2:52 Irén Marik: 6. Suite Bergamasque: Prélude 3:31 9. Preludes, Book I: Des pas sur la neige 3:10 7. Suite Bergamasque: Menuet 4:53 10. Preludes, Book II: Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses 8. Suite Bergamasque: Clair de lune 4:07 3:03 9. Pour le Piano: Prélude 3:47 Mieczysław Horszowski: Childrens Corner Suite: 10. Pour le Piano: Sarabande 5:08 11. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:48 11. Pour le Piano: Toccata 3:53 12. Jimbo’s lullaby 3:16 12. Masques 5:15 13 Serenade of the Doll 2:52 13. Estampes: Pagodes 3:49 14. The snow is dancing 3:01 14. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 3:53 15. The little Shepherd 2:16 15. Estampes: Jardins sous la pluie 3:27 16. Golliwog’s Cake walk 3:07 16. Images, Book I: Reflets dans l’eau 4:01 Mary Garden & Claude Debussy: Ariettes oubliées: 17. -

Hèléne Grimaud, Piano Program Notes Berio

Hèléne Grimaud, piano Program Notes Berio: Wasserklavier from Six Encores Wasserklavier (Water Piano, 1965) by Italian composer Luciano Berio (1925-2003) serves as a graceful dive into a diverse program of pieces all about water. Like many of Berio’s works, it references music from the past. Here, motifs from Brahms mix with hints of Schubert. Even as the music reaches ever higher toward the quiet climax—the entire piece is incredibly quiet—a repeated, descending motif drips downward, and the ending is left intentionally ambiguous. Liszt: St François de Paule marchant sur les flots Les Jeux d'eau à la Villa d'Este Though he made a name for himself as a demonically virtuosic pianist, late in life Franz Liszt (1811-1886) retreated into his Catholic faith. He spent two years living in a monastery outside Rome, where Pope Pius IX visited him and performed a Bellini aria with Liszt accompanying at the piano. Liszt in turn premiered for the Pontiff his recent religiously inspired work, St. Francis of Paola Walking on the Waters (1863). Legend has it that St. Francis of Paola, Liszt’s patron saint, was turned away trying to cross the Straits of Messina, for want of the fare. “If he is a saint, let him walk,” declared the scornful boatman. So St. Francis lifted up his cloak, which lofted like a sail and bore him safely to the other side. The surging waters roil in the left hand underneath a hymn-like theme that represents the saint. As a stately, solemn conclusion, Liszt quotes a passage from a choral work he had written also as a devotion to the saint, reusing music that sets the words “O let us preserve Love whole.” The composer explained that the story and his musical setting are meant to extol “the law of faith, which governs the laws of nature.” In 1867, Liszt accepted an invitation from a Roman Cardinal to visit the Villa d’Este, a 16th- century palace some twelve miles from Rome, perched on the site of a former Benedictine monastery. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

April 1 & 3, 2021 Walt Disney Theater

April 1 & 3, 2021 Walt Disney Theater FAIRWINDS GROWS MY MONEY SO I CAN GROW MY BUSINESS. Get the freedom to go further. Insured by NCUA. OPERA-2646-02/092719 Opera Orlando’s Carmen On the MainStage at Dr. Phillips Center | April 2021 Dear friends, Carmen is finally here! Although many plans have changed over the course of the past year, we have always had our sights set on Carmen, not just because of its incredible music and compelling story but more because of the unique setting and concept of this production in particular - 1960s Haiti. So why transport Carmen and her friends from 1820s Seville to 1960s Haiti? Well, it all just seemed to make sense, for Orando, that is. We have a vibrant and growing Haitian-American community in Central Florida, and Creole is actually the third most commonly spoken language in the state of Florida. Given that Creole derives from French, and given the African- Carribean influences already present in Carmen, setting Carmen in Haiti was a natural fit and a great way for us to celebrate Haitian culture and influence in our own community. We were excited to partner with the Greater Haitian American Chamber of Commerce for this production and connect with Haitian-American artists, choreographers, and academics. Since Carmen is a tale of survival against all odds, we wanted to find a particularly tumultuous time in Haiti’s history to make things extra difficult for our heroine, and setting the work in the 1960s under the despotic rule of Francois Duvalier (aka Papa Doc) certainly raised the stakes. -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

HOLLOWAY/DEBUSSY EN BLANC ET NOIR Thursday, March 11, Marks the World Premiere of an Orchestration by Robin Holloway of Claude Debussy’S En Blanc Et Noir

March 2004 TILSON THOMAS LEADS SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY IN PREMIERE OF HOLLOWAY/DEBUSSY EN BLANC ET NOIR Thursday, March 11, marks the world premiere of an orchestration by Robin Holloway of Claude Debussy’s En blanc et noir. Michael Tilson Thomas leads the San Francisco Symphony at Davies Symphony Hall; the program is repeated on March 12 and 13. En blanc et noir will be performed by the San Francisco Symphony on tour in Kansas City (3/16), Cleveland (3/18), New York (3/23 at Carnegie Hall), Philadelphia (3/24), and Newark (3/26). loyal and persuasive The San Francisco Symphony has consistently championed Holloway’s advocates music. In addition to commissioning En blanc et noir, the ensemble has commissioned and premiered Holloway’s Clarissa Sequence (1998), and given the American premieres of his Viola Concerto and Third Concerto for Orchestra. En blanc et noir, originally composed for piano duo in 1915, is a product of Debussy’s late period, marked by an austere beauty that stands in contrast to the lushness of better-known, earlier works such as Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, La Mer, and the Nocturnes. In orchestrating En blanc et noir, Holloway hopes to bring this seldom performed three-movement work to a wider audience. black and white, As program annotator Michael Steinberg points out, Holloway is in color acutely aware of the irony of coloring a work whose title specifi- cally calls attention to the black-and-whiteness of the piano key- board. Early in 1916, Debussy wrote to his friend Robert Godet: “These pieces draw their color, their emotion, simply from the piano, like the ‘grays’ of Velasquez, if I may so suggest?” Holloway conceives of his orchestration as an “opening out” of the music’s physical resonance, almost as though this were the freeing of a piece that has yearned to be an orchestral work all along. -

1) Aspects of the Musical Careers of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel

Edvard Grieg, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Biographical issues and a comparison of their string quartets Juliette L. Appold I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects II. Connections between Grieg, Debussy and Ravel III. Observations on their string quartets I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects Looking at the biographies of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel makes us realise, that there are few, yet some similarities in the way their career as composers were shaped. In my introductory paragraph I will point out some of these aspects. The three composers received their first musical training in their childhood, between the age of six (Grieg) and nine (Debussy) (Ravel was seven). They all entered the conservatory in their early teenage years (Debussy was 10, Ravel 14, Grieg 15 years old) and they all had more or less difficult experiences when they seriously thought about a musical career. In Grieg’s case it happened twice in his life. Once, when a school teacher ridiculed one of his first compositions in front of his class-mates.i The second time was less drastic but more subtle during his studies at the Leipzig Conservatory until 1862.ii Grieg had despised the pedagogical methods of some teachers and felt that he did not improve in his composition studies or even learn anything.iii On the other hand he was successful in his piano-classes with Carl Ferdinand Wenzel and Ignaz Moscheles, who had put a strong emphasis on the expression in his playing.iv Debussy and Ravel both were also very good piano players and originally wanted to become professional pianists. -

Brochure 2019

Saison 2019 | 2020 LA SAISON EN UN COUP D’ŒIL LES ACTIVITÉS JEUNESSE Atelier Musical et Petit concert des mélomanes p. 10 CONCERT FAMILLES LES QUATRE SAISONS DE VIVALDI Dimanche 8 mars 2020 à 15h00 Théâtre du Conservatoire p. 11 LES BÉBÉ CONCERTS 14 séances Salle Gaveau et Théâtre du Conservatoire p. 13 OFFENBACH l Dimanche 8 décembre 2019 à 17h00 Salle Gaveau p. 15 CARTE BLANCHE À MICHEL PLASSON l Dimanche 26 janvier 2020 à 17h00 Salle Gaveau p. 17 SEASONS CONCERT DE LA CHAMBRE LAMOUREUX Jeudi 5 mars 2020 à 20h00 Salle Gaveau p. 19 AILLEURS l Dimanche 29 mars 2020 à 17h00 Salle Gaveau p. 21 NUIT BLEUE Jeudi 14 mai 2020 à 20h00 Salle Gaveau p. 23 l Petit concert des mélomanes pour les 8-11 ans. Informations page 10. « Je souhaite à mes chers amis de l’Orchestre Lamoureux, dont l’Histoire est présente dans mon cœur, une belle saison avec un large public pour partager le miracle de la musique. » MICHEL PLASSON L’ORCHESTRE LAMOUREUX Orchestre symphonique français fondé en 1881 par le Son histoire est aussi liée aux noms de grandes figures violoniste Charles Lamoureux sous le nom de « Société des de la musique tels que Paul Paray, Igor Markevitch, Yutaka nouveaux Concerts », l’Orchestre Lamoureux a été créé pour Sado et plus récemment Michel Plasson. Côté solistes, il promouvoir une musique nouvelle auprès d’un large public. invite Yehudi Menuhin à ses débuts, Pablo Casals, Arthur Grumiaux, Clara Haskil, David Oistrakh, Jacques Thibaud, Dès ses premières décennies d’existence, il s’impose Karine Deshayes.. -

Susan Merdinger Repertoire List 07.01.19 Copy.Pages

SUSAN MERDINGER, Pianist and Conductor: Repertoire (2019) CONCERTOS and WORKS for PIANO(S) and ORCHESTRA: AS SOLOIST. (Additional concerti available upon request.** indicates performed with within last 5 years) Albeniz: Rapsodia Espanola, Op. 70 (Two Pianos) ** Anderson: Piano Concerto in C major Bach-Vivaldi: Concerto for Four Pianos and String Orchestra (Piano 1)** Beethoven: All Five Concerti- Op. 15, Op.19, Op.37, Op. 73 (The “Emperor”) Triple Concerto for Piano, Violin, and Cello ** Bloch: Concerto Grosso for Piano and Strings ** Brahms: No.1 in d minor, Op. 15 No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 83** Franck: Symphonic Variations** Lutoslawski: Variations on a Theme by Paganini Mozart: K.365 (Two Pianos)**, A major K. 414, G major K. 453, D minor K. 466, C major K.467**, A major K.488, C major K.503** Mendelssohn: Concerto No. 1 in g minor Concerto No. 2 in d minor Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue ** Gottschalk: L’Union**, Grande Tarantella ** Rachmaninoff: Concerto No. 2 in c minor Rhapsody on Theme of Paganini Schumann: Concerto in a, Op.54 ** Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals (Two Pianos) ** Saint-Saëns: Concerto No. 2 in g minor Tchaikovsky: No.1 in B-flat minor, Op.23 ** Liszt: No. 1 in E-flat ** Poulenc: Concerto for Two Pianos ** SOLO PIANO: SELECTED WORKS PERFORMED LIVE: (Bolded works are available on CD recording- many works available in live video format on YouTube) Aaron Alter: Piano Sonata (2012-2018) dedicated to Susan Merdinger (USA premieres in November 2018) Albéniz: Suite Española, Op. 47 J.S. Bach: French Suite No. -

2017 Preview Notes • Week Four • Persons Auditorium

2017 Preview Notes • Week Four • Persons Auditorium Saturday, August 5 at 8:00pm En blanc et noir (1915) Claude Debussy Born August 22, 1862 • Died March 25, 1918 Duration: approx. 15 minutes • Marlboro Premiere Denounced by Saint-Saëns as the aural equivalent of Cubist artwork, this piano duet indeed renders familiar subjects in unexpected and fragmented ways. Each movement is dedicated to a different person and paired with an epigraph, and that the richness of the written music, accompanying texts, and piano keys themselves—all black and white—contribute to the many colors of the piece is one example of Debussy’s wit. The first movement, a reimagined waltz, is dedicated to Serge Koussevitzky, who is remembered as a great champion of contemporary music. The second movement’s suggestion of distant bugle calls laced with quotations from the hymn “Ein Feste Burg ist unser Gott” is a haunting homage to Debussy’s friend Jacques Charlot, who perished in WWI. The work concludes with a rippling scherzando dedicated to Igor Stravinsky. Participants: Xiaohui Yang, piano; Cynthia Raim, piano Voices of Angels (1996) Brett Dean, in-residence 2017 Born October 23, 1961 Duration: approx. 25 minutes • Marlboro Premiere Brett Dean is no stranger to working with great literary texts, having just premiered his second opera, Hamlet, this summer at Glyndebourne. Like the Debussy, this piece is prefaced by an epigraph. Dean quotes the first of Rilke’s ten Duino Elegies: “Angels (it’s said) are often unable to tell whether they move/amongst the living or the dead. An eternal current/hurtles all ages through both realms for ever, and drowns out their voices in both.” As the elegy questions the conventional distinctions between beauty and terror, life and the afterlife, myth and reality, so does Dean’s composition introduce a range of seemingly contradictory perspectives.