Demilitarizing Mining Areas in the Democratic Republic of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Reports Children in Need of Humanitarian Assistance Its First COVID-19 Confirmed Case

ef Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Situation Report No. 03 © UNICEF/UN0231603/Herrmann Reporting Period: March 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers 9,100,000 • 10 March, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) reports children in need of humanitarian assistance its first COVID-19 confirmed case. As of 31 March 2020, 109 confirmed cases have been recorded, of which 9 deaths and 3 (OCHA, HNO 2020) recovered patients have been reported. During the reporting period, the virus has affected the province of Kinshasa and North Kivu 15,600,000 people in need • In addition to UNICEF’s Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) (OCHA, HNO 2020) 2020 appeal of $262 million, UNICEF’s COVID-19 response plan has a funding appeal of $58 million to support UNICEF’s response 5,010,000 in WASH/Infection Prevention and Control, risk communication, and community engagement. UNICEF’s response to COVID-19 Internally displaced people can be found on the following link (HNO 2020) 6,297 • During the reporting period, 26,789 in cholera-prone zones and cases of cholera reported other epidemic-affected areas benefiting from prevention and since January response WASH packages (Ministry of Health) UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status UNICEF Appeal 2020 9% US$ 262 million 11% 21% Funding Status (in US$) 15% Funds Carry- received forward, 10% $5.5 M $28.8M 10% 49% 21% 15% Funding gap, 3% $229.3M 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF appeals for US$ 262M to sustain the provision of humanitarian services for women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Actor Heatmap

2017 Q3 Report CONTENTS 1. Results & Overall Progress 2. Sectors 3. Regions 4. Cross-Cutting Sectors, Operations & Management 5. Business Development Services 6. Markets in Crisis 7. Women’s Economic Empowerment INTRODUCTION The third quarter was another busy one at ELAN RDC, as the programme balanced a mid-term evaluation and data verification process in addition to ongoing implementation. A number of new consultants contributed to increased activity for the technical team during the quarter, resulting in concrete workstreams on business development services (BDS), the launch of scoping to replicate existing interventions in conflict-affected Kasai Central, and a renewed focus on gender through increased support from our senior gender adviser. A number of large partnerships were finalised thanks to agreement with DFID on an improved non-objection review process, however, several large partnerships remained delayed due to multiple factors including increasing unstable market conditions. Partnerships in the energy and agriculture sectors were finalised during the quarter, while several partnerships in the financial sector faced delays. The programme has initiated a drive to increase and improve communications of programme results, resulting in an increase in visibility across various media. The launch of the Congo Coffee Atlas, completion of research for The Africa Seed Access Index (TASAI), meeting with mobile network operators to establish a lobbying platform and the finalisation of the contract for a renewable energy marketing campaign are all examples of activities through which ELAN RDC has made more market information available to the broader private sector. More details about third quarter results are found in the following slides. -

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Introduction Generale

P a g e | 1 INTRODUCTION GENERALE 0.1. Problématique Le présent mémoire porte sur les logotypes et la signification : Analyse de la dénotation et de la connotation des logotypes des banques Trust Merchant Bank (TMB) et Rawbank. En effet, Sperber1 dit qu’il n’y a rien de plus banal que la communication, car les êtres humains sont par nature des êtres communiquant par la parole, le geste, l’écrit, l’habillement et voire le silence, etc. La célèbre école de Palo Alto le dit tout haut aussi: on ne peut pas ne pas communiquer, tout est communication2. La communication, nous la pratiquons tous les jours sans y penser (mais également en y pensant) et généralement avec un succès assez impressionnant, même si parfois nous sommes confrontés à ses limites et à ses échecs. La communication demeure l’élément fondamental et complexe de la vie sociale qui rend possible l’interaction des personnes et dont la caractéristique essentielle est, selon Daniel Lagache3, la réciprocité. Elle est ce par quoi une personne influence une autre et en est influencée, car elle n’est pas indépendante des effets de son action. Morin affirme même que la communication a plusieurs fonctions : l’information, la connaissance, l’explication et la compréhension. Toutefois, pour lui, le problème central dans la communication humaine est celui de la compréhension, car on communique pour comprendre et se comprendre4. Raison pour laquelle, les chercheurs en matière de communication, surtout de notre ère, époque marquée par l’accroissement des entreprises dans la plupart des secteurs de la vie sociale, se trouvent confronté à de nouvelles problématiques qui sont autant d’enjeux pour améliorer la communication. -

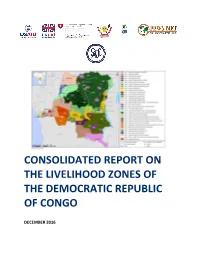

DRC Consolidated Zoning Report

CONSOLIDATED REPORT ON THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DECEMBER 2016 Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Livelihoods zoning ....................................................................................................................7 1.2 Implementation of the livelihood zoning ...................................................................................8 2. RURAL LIVELIHOODS IN DRC - AN OVERVIEW .................................................................. 11 2.1 The geographical context ........................................................................................................ 11 2.2 The shared context of the livelihood zones ............................................................................. 14 2.3 Food security questions ......................................................................................................... 16 3. SUMMARY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES .................................................... 18 CD01 COPPERBELT AND MARGINAL AGRICULTURE ....................................................................... 18 CD01: Seasonal calendar .................................................................................................................... -

A Silent Crisis in Congo: the Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika

CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika Prepared by Geoffroy Groleau, Senior Technical Advisor, Governance Technical Unit The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with 920,000 new Bantus and Twas participating in a displacements related to conflict and violence in 2016, surpassed Syria as community 1 meeting held the country generating the largest new population movements. Those during March 2016 in Kabeke, located displacements were the result of enduring violence in North and South in Manono territory Kivu, but also of rapidly escalating conflicts in the Kasaï and Tanganyika in Tanganyika. The meeting was held provinces that continue unabated. In order to promote a better to nominate a Baraza (or peace understanding of the drivers of the silent and neglected crisis in DRC, this committee), a council of elders Conflict Spotlight focuses on the inter-ethnic conflict between the Bantu composed of seven and the Twa ethnic groups in Tanganyika. This conflict illustrates how representatives from each marginalization of the Twa minority group due to a combination of limited community. access to resources, exclusion from local decision-making and systematic Photo: Sonia Rolley/RFI discrimination, can result in large-scale violence and displacement. Moreover, this document provides actionable recommendations for conflict transformation and resolution. 1 http://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2017/pdfs/2017-GRID-DRC-spotlight.pdf From Harm To Home | Rescue.org CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT ⎯ A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika 2 1. OVERVIEW Since mid-2016, inter-ethnic violence between the Bantu and the Twa ethnic groups has reached an acute phase, and is now affecting five of the six territories in a province of roughly 2.5 million people. -

Kalemie L'oubliee Kalemie the Forgotten Mwiba Lodge, Le Safari Version Luxe Mexico Insolite Not a Stranger in a Familiar La

JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE 2018 N° 20 TRIMESTRIEL N° 20 5 YEARS ANNIVERSARY 5 ANS DÉJÀ LE VOYAGE EN AFRIQUE TRAVEL in AFRICA LE VOYAGE EN AFRIQUE HAMAJI MAGAZINE N°20 • JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE 2018 N°20 • JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE HAMAJI MAGAZINE MEXICO INSOLITE Secret Mexico GRAND ANGLE MWIBA LODGE, LE SAFARI VERSION LUXE Mwiba Lodge, luxury safari at its most sumptuous VOYAGE NOT A STRANGER KALEMIE L’OUBLIEE IN A FAMILIAR LAND KALEMIE THE FORGOTTEN Par Sarah Waiswa Sur une plage du Tanganyika, l’ancienne Albertville — On the beach of Tanganyika, the old Albertville 1 | HAMAJI JUILLET N°20AOÛT SEPTEMBRE 2018 EDITOR’S NEWS 6 EDITO 7 CONTRIBUTEURS 8 CONTRIBUTORS OUR WORLD 12 ICONIC SPOT BY THE TRUST MERCHANT BANK OUT OF AFRICA 14 MWIBA LODGE : LE SAFARI DE LUXE À SON SUMMUM LUXURY SAFARI AT ITS MOST SUMPTUOUS ZOOM ECO ÉCONOMIE / ECONOMY TAUX D’INTÉRÊTS / INTEREST RATES AFRICA RDC 24 Taux d’intérêt moyen des prêts — Average loan interest rates, % KALEMIE L'OUBLIÉE — THE FORGOTTEN Taux d’intérêt moyen des dépôts d’épargne — Average interest TANZANIE - 428,8 30 % rates on saving deposits, % TANZANIA AT A GLANCE BALANCE DU COMPTE COURANT EN MILLION US$ 20 % CURRENT ACCOUNT AFRICA 34 A CHAQUE NUMERO HAMAJI MAGAZINE VOUS PROPOSE UN COUP D’OEIL BALANCE, MILLION US$ SUR L’ECONOMIE D’UN PAYS EN AFRIQUE — IN EVERY ISSUE HAMAJI MAGAZINE OFFERS 250 YOU A GLANCE AT AN AFRICAN COUNTRY’S ECONOMY 10 % TRENDY ACCRA, LA CAPITALE DU GHANA 0 SOURCE SOCIAL ECONOMICS OF TANZANIE 2016 -250 -500 0 DENSITÉ DE POPULATION PAR RÉGION / POPULATION DENSITY PER REGION 1996 -

(Odonata, Anisoptera) 2. a Revision of the Genus Neurogomphus KAR.Sch, with the Description of Some Larvae

Belgian Journal ofEntomology 6 (2004) : 91-239 Taxonomic studies on African Gomphidae (Odonata, Anisoptera) 2. A revision of the genus Neurogomphus KAR.scH, with the description of some larvae Roger CAMMAERTS Universite Libre de Bruxelles, Service de systematique et d'ecologie animates, CP 160/13, 50 av. F.D. Roosevelt, B-1050 Bruxelles, Belgium(e-mail: [email protected]). Abstract A revision of the genus Neurogomphus is presented. Seventeen species and two distinct subspecies are recognised, i.e. N. fuscifrons KARscH, 1890, N. agilis (MARTIN, 1908), N. martininus {LACROIX, 1921), N. uelensis SCHOUTEDEN, 1934, N. vicinus SCHOUTEDEN, 1934, N. wittei SCHOUTEDEN, 1934, N. chapini {KLOTS, 1944), N. featheri PINHEY, 1967, N. pallidus CAMMAERTS, 1967, N. pinheyi CAMMAERTS, 1968, N. angustisigna PINHEY, 1971, N. a/ius sp. n., N. paenuelensis sp. n., N. cocytius sp. n., N. zambeziensis sp. n., N. carlcooki sp. n., N. chapini lamtoensis subsp. n., N. dissimilis sp. n. and N. dissimilis malawiensis subsp. n. The genus is divided into two subgenera, of which Mastigogomphus (type-species: Oxygomphus chapini KLOTS, 1944) is new. Of the former described species, all but one (Karschiogomphus ghesquierei SCHOUTEDEN, 1934) remain valid, but their names were often erroneously applied to unrelated taxa. Synonymy lists give evidence of this great amount of confusion. Nevertheless, the accurate status of five of the taxa here recognised as well as of some females (N. sp. cf zambeziensis from Tanzania and sp. indet. A, B, C, D) awaits further collecting of material. Generic larval characters are specified for the first time and the larvae of some species are described, among others that of N. -

Upstream Implementation of the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected

Upstream Implementation of the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas Final Report on one-year pilot implementation of the Supplement on Tin, Tantalum, and Tungsten January 2013 © OECD 2013 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgment of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC). This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 4 SECTION II: METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................... -

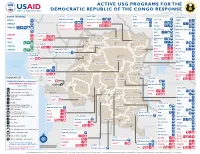

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

DR-CONGO December 2013

COUNTRY REPORT: DR-CONGO December 2013 Introduction: other provinces are also grappling with consistently high levels of violence. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DR-Congo) is the sec- ond most violent country in the ACLED dataset when Likewise, in terms of conflict actors, recent international measured by the number of conflict events; and the third commentary has focussed very heavily on the M23 rebel most fatal over the course of the dataset’s coverage (1997 group and their interactions with Congolese military - September 2013). forces and UN peacekeepers. However, while ACLED data illustrates that M23 has constituted the most violent non- Since 2011, violence levels have increased significantly in state actor in the country since its emergence in April this beleaguered country, primarily due to a sharp rise in 2012, other groups including Mayi Mayi militias, FDLR conflict in the Kivu regions (see Figure 1). Conflict levels rebels and unidentified armed groups also represent sig- during 2013 to date have reduced, following an unprece- nificant threats to security and stability. dented peak of activity in late 2012 but this year’s event levels remain significantly above average for the DR- In order to explore key dynamics of violence across time Congo. and space in the DR-Congo, this report examines in turn M23 in North and South Kivu, the Lord’s Resistance Army Across the coverage period, this violence has displayed a (LRA) in northern DR-Congo and the evolving dynamics of very distinct spatial pattern; over half of all conflict events Mayi Mayi violence across the country. The report then occurred in the eastern Kivu provinces, while a further examines MONUSCO’s efforts to maintain a fragile peace quarter took place in Orientale and less than 10% in Ka- in the country, and highlights the dynamics of the on- tanga (see Figure 2). -

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic Main objectives Impact • UNHCR provided international protection to some In 2005, UNHCR aimed to strengthen the protection 204,300 refugees in the DRC of whom some 15,200 framework through national capacity building, registra- received humanitarian assistance. tion, and the prevention of and response to sexual and • Some of the 22,400 refugees hosted by the DRC gender-based violence; facilitate the voluntary repatria- were repatriated to their home countries (Angola, tion of Angolan, Burundian, Rwandan, Ugandan and Rwanda and Burundi). Sudanese refugees; provide basic assistance to and • Some 38,900 DRC Congolese refugees returned to locally integrate refugee groups that opt to remain in the the DRC, including 14,500 under UNHCR auspices. Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC); prepare and UNHCR monitored the situation of at least 32,000 of organize the return and reintegration of DRC Congolese these returnees. refugees into their areas of origin; and support initiatives • With the help of the local authorities, UNHCR con- for demobilization, disarmament, repatriation, reintegra- ducted verification exercises in several refugee tion and resettlement (DDRRR) and the Multi-Country locations, which allowed UNHCR to revise its esti- Demobilization and Reintegration Programme (MDRP) mates of the beneficiary population. in cooperation with the UN peacekeeping mission, • UNHCR continued to assist the National Commission UNDP and the World Bank. for Refugees (CNR) in maintaining its advocacy role, urging local authorities to respect refugee rights. UNHCR Global Report 2005 123 Working environment Recurrent security threats in some regions have put another strain on this situation.