Roger Bacon on the Science of Music and Preaching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Science of Time: Roger Bacon and His Successors

CHAPTER SIX A SCIENCE OF TIME: ROGER BACON AND HIS SUCCESSORS 1. Bacon, the Calendar, and the Passion of Christ The acute criticism of the ecclesiastical calendar voiced in theCompotus emendatus of Reinher of Paderborn and—in somewhat more subdued form—in the works of Constabularius and Roger of Hereford fell on fertile ground in the following century, during which three well-known English scholars went on to pen influential treatises on the reform of the calendar, which took account of the deficiencies both of the Julian calendar with respect to the sun and the 19-year lunisolar cycle with respect to the moon. The three men in question were the astronomer John of Sacrobosco (ca. 1195–ca. 1256), who wrote a treatise De anni ratione (ca. 1232/35),1 Robert Grosseteste (ca. 1170–1253), chancellor of Oxford University and bishop of Hereford, who wrote a Compo- tus correctorius (ca. 1220/30), and—most importantly—the Franciscan polymath Roger Bacon (ca. 1214/20–ca. 1292).2 Bacon’s views on the calendar have gained particular fame for the strident tone in which they were expressed and for the fact that he was the first to present this kind of criticism to the only person in Latin Christendom who could have possibly authorized the desired change: Pope Clement IV (1265–68), to whom he addressed both his Opus 1 Theeditio princeps of this text can be found in John of Sacrobosco, Libellus de Sphaera, ed. Philipp Melanchthon (Wittenberg, 1538), Br–H3r. On the background, see Olaf Pedersen, “In Quest of Sacrobosco,” Journal for the History of Astronomy 16 (1985): 175–221; Jennifer Moreton, “John of Sacrobosco and the Calendar,” Viator 25 (1994): 229–44. -

By Bradley Steffens

1 A millennium of science as we know it thousand years ago, a math- By Bradley Steffens ematician and scholar from Basra named Abu ‘Ali al-Hasan Aibn al-Hasan ibn al-Haytham was controversially judged to be insane and placed under house arrest. To make the most of his simple surroundings, he began to study the physiology of vision and the properties of light. Upon release, he described his investigations in a mas- sive, seven-volume treatise titled Kitâb al-Manâzir· , or Book of Optics . Although missing from the many lists of the most important books ever written, Kitâb al- Manâzir changed the course of human history, giving mankind a new and effec- tive way of establishing facts about the natural world—an approach known today as the scientific method . What sets Kitâb al-Manâzir apart from earlier thirteenth century, Kitâb al-Manâzir became one of investigations into natural phenomena is that Ibn the most copied works of medieval Muslim scholar- al-Haytham included only those ideas that could be ship. Roger Bacon, the thirteenth century English friar proven with mathematics or with concrete mani- who is sometimes credited as the first true scientist festations that he called “true demonstrations,” because of his advocacy of experimentation, not only what we refer to nowadays as experiments. The read De aspectibus but summarized its findings in part use of physical experiments to establish the validity five of his Opus Majus , or Greater Work , referring of scientific claims was a departure not only from to Ibn al-Haytham by his Latinized name, Alhazen, and the works that formed the foundation of Kitâb al- describing his experiments in detail. -

The Weight of Comparing in Medieval England

The Weight of Comparing in Medieval England David Gary Shaw Abstract1 How important and common were the practices of comparing in medieval England (1150- 1500)? Focusing on activities that tended to have a pragmatic rather than purely logical in- tention, this chapter first considers medieval comparing on technical matters such as weigh- ing and measuring for the market and for agricultural efficiency. Then, however, we consider as well the more controversial comparing of humans by examining its place in taxing and ranking people; in assessing religious diversity; and even discerning the moralizing uses of comparing in literature and art. As it turns out, comparing could be perilous when humans were the subjects. Introduction It is possible that comparison might be everywhere in history, but we might also suppose that comparing might matter less in some moments and places than oth- ers. Especially given the sense that there is something distinctive and powerful about comparison in contemporary life, it is important to try to get a sense for the range, variety, and importance of modes of comparison in other times and places. In this chapter, I inquire into the place and weight of comparative thinking in Eng- land in the later medieval period. It is not an easy task, because the definition of the comparative and of com- parative practices is hardly settled. There is probably some amount of comparative activity in all European societies and moments, but we can expect that the compo- sition of the comparative practices will vary and maybe vary significantly; and that will raise problems for making any longer-term narratives. -

The Oxford Greyfriars: a Centre of Learning

THE OXFORD GREYFRIARS: A CENTRE OF LEARNING The Oxford Franciscans (Greyfriars) are significant in the history of the University of Oxford and the development of academic learning, especially scientific study. As a Studium Generale the Alchemy was the friary served as an important medieval forerunner of early “college”, within a chemistry. Alchemists network of similar Christian were famously colleges throughout Europe. concerned with the The friary had two libraries, a search for a way to scriptorium (where books were convert low grade copied out and translated), (base) metals, such many knowledgeable friars as iron and lead, into or masters, and a structured precious metals, such teaching programme. It was as gold and silver. They were also absorbed with trying to find the only rivalled in the later 13th elixir of life, which would bring the user youth and longevity and century by similar colleges perhaps immortality. in Paris and Cambridge. With such a good reputation To date, little physical evidence students came to Oxford for the practice of alchemy from across Europe, including has been identified through France, Italy, Spain, Portugal archaeological excavation. Statue to Roger Bacon in the Natural History However, in 2005 a group of Museum, Oxford and Germany. ceramic and glass alembics, The Oxford friars were inspired by great scholarly Arabic texts skillets and furnace fragments from the Islamic Golden Age during the 9th and 11th centuries. were found in an old pit (used They used these texts (translated into Latin) which enabled as a lavatory) belonging to a the ideas and knowledge from previous centuries of Islamic medieval hall buried below scholarship to be studied more widely in the emerging medieval Peckwater Quad, Christ Church, universities of Europe. -

Roger Bacon: the Christian, the Alchemist, the Enigma

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive History Honors Program History 2019 Roger Bacon: The Christian, the Alchemist, the Enigma Victoria Tobes University at Albany, State University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/history_honors Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Tobes, Victoria, "Roger Bacon: The Christian, the Alchemist, the Enigma" (2019). History Honors Program. 12. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/history_honors/12 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Honors Program by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Roger Bacon: The Christian, the Alchemist, the Enigma By: Victoria Tobes [email protected] An honors thesis presented to the Department of History, University at Albany, State University of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in History. Advisors: Dr. Patrick Nold and Dr. Mitch Aso 5/12/2019 2 ABSTRACT: This paper explores the life and work of 13th century English Franciscan friar, Roger Bacon in light of the spiritual-religious practice of alchemy. Bacon’s works in pertinence to alchemy reflect his belonging to a school of intellectual thought known as Hermeticism; which encompasses the practice of alchemy. Bacon can be placed among other philosophic practitioners of alchemy throughout history; allowing for expanded insight into the life of this medieval scholar. Throughout history, Bacon’s most well-known work, the Opus Majus, has been interpreted in a variety of ways. -

Seeing the Word : John Dee and Renaissance Occultism

Seeing the Word : John Dee and Renaissance Occultism Håkansson, Håkan 2001 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Håkansson, H. (2001). Seeing the Word : John Dee and Renaissance Occultism. Department of Cultural Sciences, Lund University. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Seeing the Word To Susan and Åse of course Seeing the Word John Dee and Renaissance Occultism Håkan Håkansson Lunds Universitet Ugglan Minervaserien 2 Cover illustration: detail from John Dee’s genealogical roll (British Library, MS Cotton Charter XIV, article 1), showing his self-portrait, the “Hieroglyphic Monad”, and the motto supercaelestes roretis aquae, et terra fructum dabit suum — “let the waters above the heavens fall, and the earth will yield its fruit”. -

The Modernity of Ibn Al-Haytham (965–1039)

6th International Congress on Physics of Radiation-Matter Interactions Tangier, Morocco, 7-9 May 2018 The Modernity of Ibn al-Haytham (965–1039) Jean Pestieau1 Centre for Cosmology, Particle Physics and Phenomenology (CP3) Université catholique de Louvain (Belgium) Abstract Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) is considered the initiator of modern optics and the scientific method. The latter is based (1) on reciprocal relation between experiment/observation and theory (expressed here in mathematical language) and (2) on primacy of the verdict of the experiment. Starting from four propositions based on experiment, Ibn al-Haytham develops geometrical optics, like Euclid, who develops geometry from five axioms. Publication of his experimental/observational data is accompanied by that of description of different steps of measurements as well as of measuring instruments in order to allow verification of results by others. It opens the way of doing modern physics, resumed five or six centuries later in Europe. Ibn al-Haytham deals with perception of images by the eye and with vision by the brain. This allows him to establish an objective conception of the world, treating the observed object as independent of the observing subject. The eye thus acquires its scientific status: that of first detector. Moreover, Ibn al-Haytham practices methodical doubt by subjecting not only the writings of the ancients but also his own prejudices to ruthless criticism. Today, while priority to verdict of practice is in many respects challenged — in particular in cosmology —, contemporaneity of Ibn al-Haytham is more evident than ever. Introduction Ibn al-Haytham, known in Western Europe as Alhazen, was born in Basra (Iraq) in 965 and died in Cairo (Egypt) in 1039.2 There he wrote several books on various subjects (astronomy, medicine, mathematics, physics, psychology, scientific method, etc.). -

Roger Bacon, Opus Majus (1267)1

1 Primary Source 8.1 ROGER BACON, OPUS MAJUS (1267)1 Broadly educated at Oxford and Paris and a member of the Franciscan religious order, Roger Bacon (1214−94) broke away from the scholastic deference to intellectual authorities and emphasized more practical, experience-based approaches to scientific advancement. Like St Thomas Aquinas, he synthesized works by a wide range of scholars and thinkers, including the great Muslim polymaths. Yet he also strongly championed experimental research and the testing of the results thus attained by other researchers in order to eliminate personal bias from the process. His relentless pursuit of truth served as inspiration for future scientists and researchers. His greatest work is Opus Major, an encyclopedia of all the knowledge of the time, which Pope Clement IV had requested that he complete and publish. The huge volume deals with philosophy, theology, grammar, mathematics, optics, ethics, and experimental science, from which the passage below is excerpted. For a link to the excerpt, click here. For the full text, click here. ON EXPERIMENTAL SCIENCE Having laid down the main points of the wisdom of the Latins as regards language, mathematics and optics, I wish now to review the principles of wisdom from the point of view of experimental science, because without experiment it is impossible to know anything thoroughly. There are two ways of acquiring knowledge, one through reason, the other by experiment. Argument reaches a conclusion and compels us to admit it, but it neither makes us certain nor so annihilates doubt that the mind rests calm in the intuition of truth, unless it finds this certitude by way of experience. -

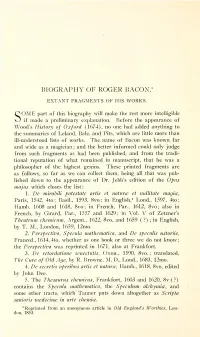

Biography of Roger Bacon. 453

; BIOGRAPHY OF ROGER BACON/ EXTANT FRAGMENTS OF HIS WORKS. SOME part of this biography will make the rest more intelUgible if made a preHminary explanation. Before the appearance of Wood's History of Oxford (1674), no one had added anything to the summaries of Leland, Bale, and Pits, which are little more than ill-understood lists of works. The name of Bacon was known far and wide as a magician; and the better informed could only judge from such fragments as had been published, and from the tradi- tional reputation of what remained in manuscript, that he was a philosopher of the highest genius. These printed fragments are as follows, so far as we can collect them, being all that was pub- lished down to the appearance of Dr. Jebb's edition of the Opus majus which closes the list: 1. De mirabili potestate artis et naturcc et nullitate magice, Paris, 1542, 4to ; Basil., 1593, 8vo ; in EngHsh,^ Lond., 1597, 4to Hamb. 1608 and 1618, 8vo ; in French, Par., 1612, 8vo ; also in French, by Girard, Par., 1557 and 1629; in Vol. V of Zetzner's Theatrimi chemicum. Argent.. 1622, 8vo, and 1659 ( ?) ; in English, by T. M., London, 1659, 12mo. 2. Perspectiva, Specula mathcmatica, and De specuUs ustoriis, Francof., 1614, 4to, whether as one book or three we do not know; the Perspectiva was reprinted in 1671, also at Frankfort. 3. De retardatione senectutis, Oxon.. 1590, 8vo. ; translated. The Cure of Old Age, by R. Browne. M. D.. Lond.. 1683. 12mo. 4. De secretis operibus artis et naturcc. Hamb., 1618, 8vo, edited by John Dee. -

1 Notes to Chapter I (1) This Very Loose Cover

Notes to Chapter I (1) This very loose cover phrase, meaning little enough without further qualifications, is selected here for its negative virtue of avoiding a too-precipitate definition of a movement — some of the complexities of which it is the purpose of this study as a whole to explore — which would in its narrowness be inevitably misleading. The terms used may, in a general way, be justified, however, by some expansion. The intellectual current referred to, and in which Dee has his place, was, it is true, hardly a “philosophy” in the sense that would imply that it flourished as any uniformly regarded, explicitly forumalated, isolable and complete, systematic body of doctrine. Rather, it exhibited itself in the main, and only so as a whole, through a multitude of partial and particular — frequently idiosyncratic — expresssions by individual thinkers active in numerous, seemingly disparate fields; hence it seems to take on a bewilderingly protean variety of forms as a consequence of such differing selections of and the accompanying changes of emphasis on elements from this philosophy (that is, which organically pertain to it viewed as a whole), and the widely differing types of subject matter with which it was brought into conjunction and applied as a more or less concealed organising framework. At the same time such manifestations have a unity in that there may be traced in them certain characteristic guiding cannons, and they are frequently to be found informed by characteristic, constantly recurring themes. Some of these the present introduction is designed to elucidate, and subsequent chapters, intended to illustrate as they functioned in a number of spheres. -

Fry.Glasses-Madeto Mug"Ifygod'sword

by Lucy Gordan Fry.glasses-Madeto Mug"ifyGod'sWord The Catholtc Church played a key role in the early production of eye$asses and tn their use tlrroughout the rvorld. Had it not beenfor missionaries, madkind mig[t havewaited centuries for this marvelousinvention yeglassesare a perfect topic for "Of gins of eyeglasses,though still somewhatshroud- Books,Art, and People."Millions of peo- ed in mystery,certainly depend on the ingenuity ple dependon themto read,not to mention and industriousnessof medievalChurchmen. that today,often designedby fashionbig- The first Churchmanto exalt the magnifying wigs like Armani, Gucci, andYves SanLaurent, function of lenseswas the English philosopher just to name a few, they are "works of art" in andscientist Roger Bacon (ca.l2l4?-L294). One themselvesas well as figuring in worksby other of the mostinfluential teachers of the 13thcentu- artists. ry he had been greatly influencedby Alhazen A year before Life magazinedeclared Guten- (965-1038),the Egyptianphysicist who men- berg "Man of the Millennium," a feature article tionedreading stones (our magnifyingglasses) in called '"The Power of Big ldeas" in Newsweek, his treatiseon optics,written around1000 AD. datedJanuary 11, 1999,reported that the atomic Born in llchester,Somersetshire, Bacon had bomb, Gutenberg'sprinting press, and reading beeneducated at the Universitiesof Oxford and g/asseshad changedthe courseof history more Paris.Soon after his returnto England,probably than all other inventionsduring the last 2,000 in around | 25l, he enteredthe religiousorder of years.Although lensesand their enlargingprop- thc Franciscansand settledin Oxford, wherehe ertieshad beenknown in ancienttimes, the ori- did researchin alchemy,optics and astronomy. Bacon was critical of the methodsof learningof back to Veniceby Marco Polo. -

English, French, Italian, and German, and the Homunculus of the Eye in Persian, and the Doll of the Eye in Turkish

TÜRK TARIH KURUMU BELLETEN Cilt: XLVII Temmuz 1983 Say~ : 187 A POSSIBLE INFLUENCE, IN THE FIELD OF PHYSIOLOGICAL OPTICS, OF IBN SINA ON IBN AL-HAYTHAM* Professor AYDIN SAYILI Ibn al-Haytham was widely known in late medieval Europe where he was called Alhazen, the Latinized form of his first name Al-Hasan. Concerning him David C. Lindberg writes: "Alhazen was a prolific writer on all aspects of science and natural philosophy. More than two hundred works are attributed to him by Ibn abi Usaybi`a, including ninety of which Alhazen himself acknowledged authorship. "Alhazen's extant works on the subjet of optics are the following: (~ ) Kitab al-Manazir (Book of Optics), translated into Latin as De aspectibus or Perspectiva, (2) On the Paraboloidal Burning Mirror, translated into Latin as De speculis comburentibus, (3) On the Shperical Burning Mirror, (4) On the Burning Sphere, (5) On Light, (6) On the Rainbow and Halo, (7) On the Nature of Shadows, (8) On the Form of the Eclipse, which deals with the theory of radiation through apertures, (9) On the Light of the Moon, and (i o) On the Light of the Stars. Finally a section on optics appears in Alhazen's (ii) Doubts Concerning Ptolemy. Another work frequently attributed to Alhazen, On the Twilight (translated * This is a paper prepared for the International Conference on Science in Islamic Polity, Its Past, Present, and Future, held in November 19-24, 1983 in Islamabad, Pakistan. 666 AYDIN SAYILI into Latin as De crepusculis) was actually written by Abu <Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Mu<adh.