John Fowles' Narrative Stylistics in the Collector, Daniel Martin, and a Maggot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Translating Ironic Intertextual Allusions.” In: Martínez Sierra, Juan José & Patrick Zabalbeascoa Terran (Eds.) 2017

Recibido / Received: 30/06/2016 Aceptado / Accepted: 16/11/2016 Para enlazar con este artículo / To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/MonTI.2017.9.5 Para citar este artículo / To cite this article: LIEVOIS, Katrien. (2017) “Translating ironic intertextual allusions.” In: Martínez Sierra, Juan José & Patrick Zabalbeascoa Terran (eds.) 2017. The Translation of Humour / La traducción del humor. MonTI 9, pp. 1-24. TRANSLATING IRONIC INTERTEXTUAL ALLUSIONS Katrien Lievois [email protected] Université d’Anvers Translated from French by Trish Van Bolderen1 [email protected] University of Ottawa Abstract Based on a corpus consisting of Albert Camus’s La Chute, Hugo Claus’s Le chagrin des Belges, Fouad Laroui’s Une année chez les Français and their Dutch versions, this article examines the ways in which ironic intertextual allusions are translated. It begins with a presentation of the theoretical concepts underpinning the analysis and subsequently identifies, through a detailed study, the following nine strategies: standard translation; literal translation; translation using markers; non-translation; translation into a third language; glosses; omissions; substitutions using intertextuality from the target culture; and substitutions using architextuality. Resume A partir d’un corpus constitué de La Chute d’Albert Camus, du Chagrin des Belges de Hugo Claus et d’Une année chez les Français de Fouad Laroui, ainsi que leurs versions néerlandaises, cette contribution s’intéresse à la traduction de l’allusion intertextuelle ironique. Elle présente d’abord les concepts théoriques qui sous-tendent l’analyse, pour ensuite étudier plus en détail les 9 stratégies rencontrées : la traduction standard, la traduction littérale, la traduction avec marquage, la non-traduction, la traduction primera 1. -

Fiction John Fowles, the Collector, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1963

BIBLIOGRAPHY WORKS BY JOHN FOWLES Fiction John Fowles, The Collector, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1963. —— Daniel Martin, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1977. —— The Ebony Tower, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1974. —— The French Lieutenant’s Woman, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1969. —— A Maggot, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1985. —— The Magus, New York: Dell Publishing, 1978. —— Mantissa, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1982. Nonfiction John Fowles, The Aristos, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1964. —— The Enigma of Stonehenge, New York: Summit Books, 1980. —— Foreword, in Ourika, by Claire de Duras, trans. John Fowles, New York: MLA, 1994, xxix-xxx. —— Islands, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1978. —— Lyme Regis Camera, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1990. —— Shipwreck, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1975. —— A Short History of Lyme Regis, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1982. —— Thomas Hardy’s England, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1984. —— The Tree, New York: The Ecco Press, 1979. Translations Claire de Duras, Ourika, trans. John Fowles, New York: MLA, 1994. 238 John Fowles: Visionary and Voyeur Essays John Fowles, “Gather Ye Starlets”, in Wormholes, ed. Jan Relf, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998, 89-99. —— “I Write Therefore I Am”, in Wormholes, ed. Jan Relf, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998, 5-12. —— “The J.R. Fowles Club”, in Wormholes, ed. Jan Relf, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998, 67. —— “John Aubrey and the Genesis of the Monumenta Britannica”, in Wormholes, ed. Jan Relf, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998, 175-96. —— “The John Fowles Symposium, Lyme Regis, July 1996”, in Wormholes, ed. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR THIRTY-NINE $9 95 IN THE US . c n I , s r e t c a r a h C l e v r a M 3 0 0 2 © & M T t l o B k c a l B FAN FAVORITES! THE NEW COPYRIGHTS: Angry Charlie, Batman, Ben Boxer, Big Barda, Darkseid, Dr. Fate, Green Lantern, RETROSPECTIVE . .68 Guardian, Joker, Justice League of America, Kalibak, Kamandi, Lightray, Losers, Manhunter, (the real Silver Surfer—Jack’s, that is) New Gods, Newsboy Legion, OMAC, Orion, Super Powers, Superman, True Divorce, Wonder Woman COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .78 TM & ©2003 DC Comics • 2001 characters, (some very artful letters on #37-38) Ardina, Blastaar, Bucky, Captain America, Dr. Doom, Fantastic Four (Mr. Fantastic, Human #39, FALL 2003 Collector PARTING SHOT . .80 Torch, Thing, Invisible Girl), Frightful Four (Medusa, Wizard, Sandman, Trapster), Galactus, (we’ve got a Thing for you) Gargoyle, hercules, Hulk, Ikaris, Inhumans (Black OPENING SHOT . .2 KIRBY OBSCURA . .21 Bolt, Crystal, Lockjaw, Gorgon, Medusa, Karnak, C Front cover inks: MIKE ALLRED (where the editor lists his favorite things) (Barry Forshaw has more rare Kirby stuff) Triton, Maximus), Iron Man, Leader, Loki, Machine Front cover colors: LAURA ALLRED Man, Nick Fury, Rawhide Kid, Rick Jones, o Sentinels, Sgt. Fury, Shalla Bal, Silver Surfer, Sub- UNDER THE COVERS . .3 GALLERY (GUEST EDITED!) . .22 Back cover inks: P. CRAIG RUSSELL Mariner, Thor, Two-Gun Kid, Tyrannus, Watcher, (Jerry Boyd asks nearly everyone what (congrats Chris Beneke!) Back cover colors: TOM ZIUKO Wyatt Wingfoot, X-Men (Angel, Cyclops, Beast, n their fave Kirby cover is) Iceman, Marvel Girl) TM & ©2003 Marvel Photocopies of Jack’s uninked pencils from Characters, Inc. -

The Idea of Mimesis: Semblance, Play, and Critique in the Works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 8-2012 The idea of mimesis: Semblance, play, and critique in the works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno Joseph Weiss DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Weiss, Joseph, "The idea of mimesis: Semblance, play, and critique in the works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno" (2012). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 125. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/125 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Idea of Mimesis: Semblance, Play, and Critique in the Works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy October, 2011 By Joseph Weiss Department of Philosophy College of Liberal Arts and Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois 2 ABSTRACT Joseph Weiss Title: The Idea of Mimesis: Semblance, Play and Critique in the Works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno Critical Theory demands that its forms of critique express resistance to the socially necessary illusions of a given historical period. Yet theorists have seldom discussed just how much it is the case that, for Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. -

EARLY MODERN WOMEN WRITERS and HUMILITY AS RHETORIC: AEMILIA LANYER's TABLE-TURNING USE of MODESTY Thesis Submitted to the Co

EARLY MODERN WOMEN WRITERS AND HUMILITY AS RHETORIC: AEMILIA LANYER’S TABLE-TURNING USE OF MODESTY Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in English By Kathryn L. Sandy-Smith UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio August 2013 EARLY MODERN WOMEN WRITERS AND HUMILITY AS RHETORIC: AEMILIA LANYER’S TABLE-TURNING USE OF MODESTY Name: Sandy-Smith, Kathryn Louise APPROVED BY: ________________________ Elizabeth Ann Mackay, Ph.D. Committee Co-chair ________________________ Sheila Hassell Hughes, Ph.D. Committee Member __________________________ Rebecca Potter, Ph.D. Committee Co-chair ii ABSTRACT EARLY MODERN WOMEN WRITERS AND HUMILITY AS RHETORIC: AEMILIA LANYER’S TABLE-TURNING USE OF MODESTY Name: Sandy-Smith, Kathryn L. University of Dayton Advisor: Elizabeth Mackay, Ph.D. 16th and 17th century women’s writing contains a pervasive language of self-effacement, which has been documented and analyzed by scholars, but the focus remains on the sincerity of the act, even though humility was often employed as a successful rhetorical tool by both classic orators and Renaissance male writers. Aemilia Lanyer’s Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum has been read in this tradition of sincere humility, and even when it has not, scholars have focused on the dedicatory paratext, thus minimizing Lanyer’s poetic prowess. I argue that Lanyer’s poem-proper employs modesty as a strategic rhetorical device, giving added credibility and importance to her work. By removing the lens of modesty as sincerity, I hope to encourage a reexamination of the texts of Renaissance women and remove them from their ‘silent, chaste and obedient’ allocation by/for the modern reader. -

Doctor Strange Comics As Post-Fantasy

Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Karen Swenson, Chair Nancy A. Metz Katrina M. Powell April 15, 2019 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Fantasy, Comics Studies, Postmodernism, Post-Fantasy Copyright 2019, Jessie L. Rogers Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers (ABSTRACT) This thesis demonstrates that Doctor Strange comics incorporate established tropes of the fantastic canon while also incorporating postmodern techniques that modernize the genre. Strange’s debut series, Strange Tales, begins this development of stylistic changes, but it still relies heavily on standard uses of the fantastic. The 2015 series, Doctor Strange, builds on the evolution of the fantastic apparent in its predecessor while evidencing an even stronger presence of the postmodern. Such use of postmodern strategies disrupts the suspension of disbelief on which popular fantasy often relies. To show this disruption and its effects, this thesis examines Strange Tales and Doctor Strange (2015) as they relate to the fantastic cornerstones of Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings and Rowling’s Harry Potter series. It begins by defining the genre of fantasy and the tenets of postmodernism, then it combines these definitions to explain the new genre of postmodern fantasy, or post-fantasy, which Doctor Strange comics develop. To show how these comics evolve the fantasy genre through applications of postmodernism, this thesis examines their use of otherworldliness and supernaturalism, as well as their characterization and narrative strategies, examining how these facets subvert our expectations of fantasy texts. -

Fantastic Four Omnibus Volume 2 (New Printing) Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FANTASTIC FOUR OMNIBUS VOLUME 2 (NEW PRINTING) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stan Lee | 832 pages | 17 Dec 2013 | Marvel Comics | 9780785185673 | English | New York, United States Fantastic Four Omnibus Volume 2 (new Printing) PDF Book It also introduces the groundbreaking if problematic Black Panther and the high weirdness of the Inhumans, along with other major players in the Marvel Universe to come. While I already knew Doom and Reed went to college together, it was nice to read the story for the first time. Marvel Omnibus time! Read more Added to basket. While I already knew Doom and Reed went to college together, it was nice to read the story for the first time. I guess it just showed how the world building was going on off the pages as well as on them. Please try again or alternatively you can contact your chosen shop on or send us an email at. Collecting the greatest stories from the World''s Greatest Comics Magazine in one, massive collector''s edition that has been painstakingly restored and recolored from the sharpest material in the Marvel Archives. Your order is now being processed and we have sent a confirmation email to you at. Fast Customer Service!!. Sort order. In this volume the two great storylines are the introduction of the Inhumans, Galactus and the Silver Surfer. Prices and offers may vary in store. The Fantastic Four comics from this era are consistently good value, even if some are more exciting than others. The Fantastic Four comics from this era are consistently good value, even if some are more exciting than others. -

Continuity in Color: the Persistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2016 Continuity in Color: The eP rsistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes McKinley May Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation May, McKinley, "Continuity in Color: The eP rsistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes" (2016). University Honors Program Theses. 170. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/170 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Continuity in Color: The Persistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Literature and Philosophy. By McKinley May Under the mentorship of Joe Pellegrino ABSTRACT This paper examines the symbolism of the colors black, white, and red from ancient times to modern. It explores ancient myths, the Grimm canon of fairy tales, and modern film and television tropes in order to establish the continuity of certain symbolisms through time. In regards to the fairy tales, the examination focuses solely on the lesser-known stories, due to the large amounts of scholarship surrounding the “popular” tales. The continuity of interpretation of these three major colors (black, white, and red) establishes the link between the past and the present and demonstrates the influence of older myths and beliefs on modern understandings of the colors. -

Double-Edged Imitation

Double-Edged Imitation Theories and Practices of Pastiche in Literature Sanna Nyqvist University of Helsinki 2010 © Sanna Nyqvist 2010 ISBN 978-952-92-6970-9 Nord Print Oy Helsinki 2010 Acknowledgements Among the great pleasures of bringing a project like this to com- pletion is the opportunity to declare my gratitude to the many people who have made it possible and, moreover, enjoyable and instructive. My supervisor, Professor H.K. Riikonen has accorded me generous academic freedom, as well as unfailing support when- ever I have needed it. His belief in the merits of this book has been a source of inspiration and motivation. Professor Steven Connor and Professor Suzanne Keen were as thorough and care- ful pre-examiners as I could wish for and I am very grateful for their suggestions and advice. I have been privileged to conduct my work for four years in the Finnish Graduate School of Literary Studies under the direc- torship of Professor Bo Pettersson. He and the Graduate School’s Post-Doctoral Researcher Harri Veivo not only offered insightful and careful comments on my papers, but equally importantly cre- ated a friendly and encouraging atmosphere in the Graduate School seminars. I thank my fellow post-graduate students – Dr. Juuso Aarnio, Dr. Ulrika Gustafsson, Dr. Mari Hatavara, Dr. Saija Isomaa, Mikko Kallionsivu, Toni Lahtinen, Hanna Meretoja, Dr. Outi Oja, Dr. Merja Polvinen, Dr. Riikka Rossi, Dr. Hanna Ruutu, Juho-Antti Tuhkanen and Jussi Willman – for their feed- back and collegial support. The rush to meet the seminar deadline was always amply compensated by the discussions in the seminar itself, and afterwards over a glass of wine. -

Dalrev Vol68 Iss3 Pp288 301.Pdf (6.837Mb)

Frederick M. Holmes The Novelist as Magus: John Fowles and the Function of Narrative It is difficult to trap John Fowles the writer under conceptual nets. Having announced his intention not "to walk into the cage labelled 'novelist,' " 1 he has published, in addition to his best-selling novels, a volume of poems, a philosophical tract, and discursive prose on such subjects as Stonehenge, the Scilly Isles, trees, cricket, and Thomas Hardy. When we restrict our attention to his fiction, he is equally hard to classify unambiguously. His aesthetic has been called "conservative and traditional,''2 and yet John Barth includes Fowles, along with himself, in a group of avant-garde novelists who have been tagged postmodernist.J On the one hand, Fowles has championed realism, 4 repudiated art which exalts technique and style at the expense of human content,5 endorsed the ancient dictum that the function of art is to entertain and instruct, 6 and announced a didactic intention to "improve society at large."7 To some extent, his novels do realize these traditional aims. They usually create an intense illusion that real human dramas are being played out before the reader's eyes. Each of these dramas is a didactic exemplum of Fowles's belief in the value of freedom. 8 On the other hand, though, Fowles has affirmed the reality of the crisis often said to have made the contemporary novel prob lematic.9 This awareness has rendered his fictions self-referential in ways that cast doubt upon their mimetic capacity. His narratives frequently expose themselves as arbitrary, decentred, and inconclusive structures of words cut loose from any legitimating origin or trans cendent authority. -

Glossary of Literary Terms

Glossary of Critical Terms for Prose Adapted from “LitWeb,” The Norton Introduction to Literature Study Space http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/litweb10/glossary/C.aspx Action Any event or series of events depicted in a literary work; an event may be verbal as well as physical, so that speaking or telling a story within the story may be an event. Allusion A brief, often implicit and indirect reference within a literary text to something outside the text, whether another text (e.g. the Bible, a myth, another literary work, a painting, or a piece of music) or any imaginary or historical person, place, or thing. Ambiguity When we are involved in interpretation—figuring out what different elements in a story “mean”—we are responding to a work’s ambiguity. This means that the work is open to several simultaneous interpretations. Language, especially when manipulated artistically, can communicate more than one meaning, encouraging our interpretations. Antagonist A character or a nonhuman force that opposes, or is in conflict with, the protagonist. Anticlimax An event or series of events usually at the end of a narrative that contrast with the tension building up before. Antihero A protagonist who is in one way or another the very opposite of a traditional hero. Instead of being courageous and determined, for instance, an antihero might be timid, hypersensitive, and indecisive to the point of paralysis. Antiheroes are especially common in modern literary works. Archetype A character, ritual, symbol, or plot pattern that recurs in the myth and literature of many cultures; examples include the scapegoat or trickster (character type), the rite of passage (ritual), and the quest or descent into the underworld (plot pattern). -

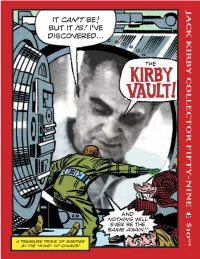

J a C K Kirb Y C Olle C T Or F If T Y- Nine $ 10

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FIFTY-NINE $10 FIFTY-NINE COLLECTOR KIRBY JACK IT CAN’T BE! BUT IT IS! I’VE DISCOVERED... ...THE AND NOTHING WILL EVER BE THE SAME AGAIN!! 95 A TREASURE TROVE OF RARITIES BY THE “KING” OF COMICS! Contents THE OLD(?) The Kirby Vault! OPENING SHOT . .2 (is a boycott right for you?) KIRBY OBSCURA . .4 (Barry Forshaw’s alarmed) ISSUE #59, SUMMER 2012 C o l l e c t o r JACK F.A.Q.s . .7 (Mark Evanier on inkers and THE WONDER YEARS) AUTEUR THEORY OF COMICS . .11 (Arlen Schumer on who and what makes a comic book) KIRBY KINETICS . .27 (Norris Burroughs’ new column is anything but marginal) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .30 (the shape of shields to come) FOUNDATIONS . .32 (ever seen these Kirby covers?) INFLUENCEES . .38 (Don Glut shows us a possible devil in the details) INNERVIEW . .40 (Scott Fresina tells us what really went on in the Kirby household) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .42 (Adam McGovern & an occult fave) CUT-UPS . .45 (Steven Brower on Jack’s collages) GALLERY 1 . .49 (Kirby collages in FULL-COLOR) UNEARTHED . .54 (bootleg Kirby album covers) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . .55 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) GALLERY 2 . .56 (unused DC artwork) TRIBUTE . .64 (the 2011 Kirby Tribute Panel) GALLERY 3 . .78 (a go-go girl from SOUL LOVE) UNEARTHED . .88 (Kirby’s Someday Funnies) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .90 PARTING SHOT . .100 Front cover inks: JOE SINNOTT Back cover inks: DON HECK Back cover colors: JACK KIRBY (an unused 1966 promotional piece, courtesy of Heritage Auctions) This issue would not have been If you’re viewing a Digital possible without the help of the JACK Edition of this publication, KIRBY MUSEUM & RESEARCH CENTER (www.kirbymuseum.org) and PLEASE READ THIS: www.whatifkirby.com—thanks! This is copyrighted material, NOT intended for downloading anywhere except our The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol.