Conceptualizing Ambush Marketing: Developing a Typology of Ambush Strategy and Exploring the Managerial Implications for Sport Sponsors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lifetime Contracts in Sports

Lifetime Contracts In Sports Briggs mechanize his periodontics taper palatially or unkindly after Hamilton syncretizing and caskets phonologically, thoughtful and woodier. When Skye nebulizes his hoofbeat escribe not exceedingly enough, is Hezekiah galactagogue? Cuspidate and flat Jacques nark her calfskin pauperising or spoor vernally. As it was played in my wildest dreams. Ceo jeff bezos and wear their lifetime contracts in sports industry, they presented it must open after a driven by written permission of parol evidence and do you want to. Deion sanders is not believe to explore the terms of signature nike? Underscore may not lifetime contracts in sports. What can get miles golden state vs cristiano ronaldo now an extended several cities havebegun to lifetime contracts in a lifetime athletes in sunny anaheim, they educate theathlete about them cope with his way. The subscriber data are collectibles worth it in sports contracts on extreme approach of his athletic eligibility. Adidas to the homepage to import businessinto the team, buffet has deals with his deal paid athlete earns a ball club that. The lifetime contracts are. Crystal palace seemingly insignificant amount to support a mere three years goes into another person at select locations in. Beijing automotive group package it window passes, lifetime contracts in sports news, if the market for me, wine tastings and mental deterioration necessitating commitment. This deal for a hit no further payments are connected in their words would have given the theme will declare that kind of the access? And had even greater knowledge of similar that trammell is signed lifetime contracts in sports. -

Dossier-Ccf.Pdf

2 LA CIBLE COLLECTION CAPSULE A la création de la marque, Lacoste vise un public BCBG (bon chic bon genre), la C’est a l’occasion de son 85e anniversaire en printemps 2018 que Lacoste souhaite a bourgeoisie parisienne, mais cette clientèle s’amoindri et devient vieillissante. Dans les transformé son nom en collaborant avec des artistes. Mathias Augustyniak et Michael années 90 la marque s’adresse alors à la descendance même de ce public élitiste et Amzalag (M/M), le duo célébré d’artistes et designers français, ont conçu un alphabet privilégié, la jeunesse de 20-35 ans, dynamique, sportive, urbain, mais toujours BCBG. Pour géométrique bicolore pour réinterpréter le crocodile le plus connu au monde. Ils ont cela, la marque propose des vêtements « modes » et « décontractés » mais aussi des ingénieusement reconfiguré les lettres de "Lacoste" en forme de son célèbre crocodile. pièces d’habillement de sport avec un sens aigu du gout. Des tenu plus « sexy », moins Ainsi, le E représente les mâchoires, et le L est la queue. La collection propose des « ennuyeuse », plus jeune, pour devenir désirable au plus grand nombre. Aujourd’hui, la vêtements et accessoires avec la nouvelle géométrie graphique remplaçant le logo marque est toujours réputée pour la qualité de ses vêtements et elle n’est plus destinée crocodile. uniquement aux hommes et aux pratiquants des sports de ci-dessus. L’élargissement de sa Cette collaboration est une occasion pour eux de prouver une fois de plus leur valeurs gamme lui a également permis de toucher la cible féminine qui était alors très peu du à un changement et un renouveau prouvant une source de dynamisme et un concernée par la marque. -

Análisis De Contenido Del Comercial De Nike De La Campaña “Escribe El Futuro” En El Mundial 2010 Y Su Contextualización En El Discurso De La Postmodernidad

ANÁLISIS DE CONTENIDO DEL COMERCIAL DE NIKE DE LA CAMPAÑA “ESCRIBE EL FUTURO” EN EL MUNDIAL 2010 Y SU CONTEXTUALIZACIÓN EN EL DISCURSO DE LA POSTMODERNIDAD DIANA MARCELA LOANGO CAVIEDES SARA MARÍA ZAMORA CUELLAR UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE OCCIDENTE FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL DEPARTAMENTO DE PUBLICIDAD Y DISEÑO PROGRAMA DE COMUNICACIÓN PUBLCITARIA SANTIAGO DE CALI 2012 ANÁLISIS DE CONTENIDO DEL COMERCIAL DE NIKE DE LA CAMPAÑA “ESCRIBE EL FUTURO” EN EL MUNDIAL 2010 Y SU CONTEXTUALIZACIÓN EN EL DISCURSO DE LA POSTMODERNIDAD DIANA MARCELA LOANGO CAVIEDES SARA MARÍA ZAMORA CUELLAR Pasantía de Investigación con el grupo GIMPU (Grupo de Investigación de Mercadeo y Publicidad) Para optar al título de Comunicador Publicitario Directora: CARMEN ELISA LERMA Publicista y Psicóloga UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE OCCIDENTE FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL DEPARTAMENTO DE PUBLICIDAD Y DISEÑO PROGRAMA DE COMUNICACIÓN PUBLCITARIA SANTIAGO DE CALI 2012 Nota de aceptación: Aprobado por el Comité de Grado en cumplimiento de los requisitos exigidos por la Universidad Autónoma de Occidente para optar al título de Comunicador Publicitaria. PAOLA GÓMEZ Jurado CARMEN ELISA LERMA Director Santiago de Cali, 13 de Febrero de 2012 3 AGRADECIMIENTOS Principalmente le agradezco a Dios, por haberme permitido emprender mis estudios de Comunicación publicitaria satisfactoriamente, por darme la fortaleza y la motivación de seguir adelante con el proceso y con este proyecto de investigación, el cual fue desarrollado con el mayor esfuerzo. Asimismo a mi madre y mi padre por estar ahí siempre, apoyando, animando, levantando en los momentos de altibajo y alentando en las situaciones de cansancio donde uno creo que el culminar este proceso será totalmente complejo; por estas razones y mucho más, les agradezco con todo mi corazón el verdadero esfuerzo que hacen por mí, por lo que soy y por todo lo que puede llegar a ser. -

2016 Veth Manuel 1142220 Et

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Selling the People's Game Football's transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor State Veth, Karl Manuel Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 Selling the People’s Game: Football's Transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor States K. -

Vörubæklingur Fjölbreytt Úrval

02.06.12 Vörubæklingur Fjölbreytt úrval Opnunartímar Sportheima Mánudag 10-20 Hér erum við ! Þriðjudag 10-20 Miðvikudag 10-20 Fimmtudag 10-20 Föstudag 10-20 Laugardag 10-20 Sunnudag 10-20 Bíldshöfði 20 Sími 420-1234 Skrifstofusími: 420-1324 Fax: 420-4321 [email protected] Nike Tiempo Nike Tiempo Legend Nike Tiempo Legend Legend IV Elite FG IV Elite FG IV Elite FG Verð: 77.770 Verð:65,890 Verð:61,900 Nike Tiempo Legend Nike - Tiempo Nike Tiempo Legend IV Elite FG Legend Elite SG IV Elite FG Verð:54,000 Verð:35900 Verð:54000 Nike Mercurial Vapor Nike Mercurial Nike Mercurial Vapor VIII FG Vapor VIII FG VIII FG Verð:35900 Verð:35900 Verð:35900 Nike T90 Laser IV KL Nike T90 Laser IV Nike T90 Laser IV KL SG-Pro KL-FG -FG Verð:33300 Verð:33300 Verð:33300 Bíldshöfði 20 Sími 420-1234 Skrifstofusími: 420-1324 Fax: 420-4321 [email protected] Nike CTR360 Maestri Nike CTR360 Maestri Nike CTR360 Maestri II FG II FG II FG Verð:32200 Verð:32200 Verð:26500 Nike CTR360 Maestri adidas F50 adizero adidas F50 adizero II FG TRX FG TRX FG Leather Verð:30800 Verð:37000 Verð:37000 adidas F50 adizero adidas F50 adizero adidas F50 adizero TRX FG Leather TRX FG TRX FG Verð: 37900 Verð:37900 Verð:29400 adidas F50 adizero adidas Predator LZ adidas adipower TRX FG Leather TRX FG Predator TRX FG Verð:29400 Verð:38000 Verð:37000 Bíldshöfði 20 Sími 420-1234 Skrifstofusími: 420-1324 Fax: 420-4321 [email protected] adidas adipower adidas adipower adidas adipure Predator TRX FG Predator DB TRX FG 11Pro TRX FG Verð: 30800 Verð:30000 Verð: 29700 adidas adipure adidas -

Football, Nationalism and the Chants of Palestinian Resistance in Jordan

“Allah! Wehdat! Al-Quds Arabiya!”: Football, Nationalism and the chants of Palestinian Resistance in Jordan by Joshua MacKenzie B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2010 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Joshua MacKenzie 2015 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2015 Approval Name: Joshua MacKenzie Degree: Master of Arts (History) Title: “Allah! Wehdat! Al-Quds Arabiya!”: Football, Nationalism and the Chants of Palestinian Resistance in Jordan Examining Committee: Chair: Mary-Ellen Kelm Associate Professor Paul Sedra Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Thomas Kuehn Supervisor Associate Professor Derryl MacLean Supervisor Associate Professor Adel Iskandar External Examiner Assistant Professor School of Communication Simon Fraser University Date Defended/Approved: November 27, 2015 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract After the Jordanian Civil War in 1970—which saw the Jordanian army defeat Palestinian guerrillas, the death of thousands of Palestinians living in Jordan and the exile of Palestinian political organizations and leaders from refugee camps—Palestinians in Jordan became politically and socially marginalized. Despite these marginalizations, Palestinians in Jordan always had access to sport. This thesis will examine how the football club, al-Wehdat, plays a role in creating and establishing identity and nationalism for Palestinians in Jordan. By using oral history, I move beyond the narrative of a homogenous Palestinian identity and demonstrate the complexities of Palestinian identities. Moreover, utilizing oral history in my thesis challenges the notion of football being cathartic, and demonstrates how al-Wehdat fans are able to: A) manoeuvre within the stadium, despite being under constant surveillance, B) to continue to use al-Wehdat as a political platform, predominantly through their chants, and C) to develop Palestinian identity and nationalism in Jordan. -

Carlos Casanova Junior.Pdf

Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo Carlos Casanova Junior A Pátria de Chuteiras Um estudo da produção de sentido da marca Nike no Brasil Mestrado em Comunicação e Semiótica São Paulo 2013 Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo Carlos Casanova Junior A Pátria de Chuteiras Um estudo da produção de sentido da marca Nike no Brasil Dissertação apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para a obtenção do título de MESTRE em Comunicação e Semiótica, sob a orientação do Professor Doutor Oscar Cesarotto. São Paulo 2013 Carlos Casanova Junior A Pátria de Chuteiras Um Estudo da Produção de Sentido da Marca Nike no Brasil Mestrado em Comunicação e Semiótica Aprovado em: _____________ Banca Examinadora Prof. Dr. Oscar Cesarotto (Orientador) Instituição: PUC-SP Assinatura______________________ Prof. Dr.________________________________________________________ Instituição: ________________________Assinatura______________________ Prof. Dr.________________________________________________________ Instituição: ________________________Assinatura______________________ Para Rafael Lopes Casanova e Kelly Lopes Casanova Os melhores sonhos da minha vida. AGRADECIMENTO Esta dissertação reflete um sonho antigo. Daquele que se sonha acordado, e do qual não se quer acordar. Este trabalho que agora se inicia é a parte final deste sonho. E se o realizei, foi por intermédio de algumas pessoas, sem as quais esta dissertação não poderia se iniciar. Em princípio, agradeço a Deus, por ter dado o dom da vida e ter colocado nela pessoas que sempre abençoaram o meu caminho. Agradeço ao meu orientador, Prof. Dr. Oscar Cesarotto, por ter sempre acreditado em meu potencial, quando, muitas vezes, nem eu mesmo acreditava, Com suas sábias palavras, o seu leve sotaque argentino e o seu desenvolvimento intelectual, ampliou minha concepção de vida acadêmica e me fez mergulhar em outras águas. -

1 a Few Other Things That Kill a Relationship and Totally Piss You Off Is

#1 A few other things that kill a relationship and totally piss you off is when your partner is always on the computer looking at porno or talking to other woman on webcam then hurrying to turn off the computer or switch to another site when you walk in the room also when they are quick to answer their mobile phone and tell you it was the wrong number or not tell you who it was. #2 First thing I get up in the morning I hit a key and start it up! I am a bonifide computer junkie! I wasn't always ,but ever since I got a computer a year ago and learned how to use one it is my life it seems. #3 Hello! my dear! / I am a pretty girl from Russia and very much want to meet you. / I am very optimistic but within reasonable limits. But still there is a lack of one person in my fate. / That is why I'm here. I am waiting for my only man to come to my life. Doors to my soul are open for him. / Look at my pictures: http://lavdate.ru/?vu I will be waiting for you. #4 And you can do it to your conscience You can do it all the time You can do it with a vengeance In the morning after nine But you know You'll always be waiting Always be waiting For someone else to call #5 The usual diversion tactic, the only problem are the touts. What about the false companies set up by the likes of Seb Coe and Jonathon Edwards? Six figure cheques written out for the usual s**t, `consultancy fees`. -

Dirty Secrets of the P10

£1.20 Weekend edition Saturday/Sunday December 2-3 2017 Morning Star Incorporating the Daily Worker For peace and socialism www.morningstaronline.co.uk DIRTY SECRETS OF THE P10 As Tories cut benefi ts across Britain for festive season, people are protesting for the ending of Theresa May’s disastrous universal credit mess UNITE RALLIES TO STOP GRINCH RUINING XMAS by Peter Lazenby benefi t cuts and delayed payments have been driven to using foodbanks to survive. CHRISTMAS has been cancelled for The government has admitted that hundreds of thousands of families the universal credit claimants’ hel- claiming universal credit, but dem- pline will be closed for most of the onstrators up and down the country Christmas period, making life even will take to the streets today to more diffi cult for those needing demand action. advice and emergency help. Trade unionists and campaigners Many activists will run town-cen- will turn out in more than 70 towns tre stalls today to provide some of and cities across Britain, accusing the current half a million victims of the government of “abolishing Christ- the scheme with help and advice. mas” for victims of its benefi ts fi asco. Unite Community head Liane The day of action, organised by Groves said: “Despite knowing that Unite Community — part of Britain’s universal credit causes serious prob- biggest trade union — is aimed at lems for those claiming it, the gov- putting pressure on the government ernment is ploughing ahead regard- to “stop and fi x” universal credit less while claimants are descending before even more families are forced into debt, relying on foodbanks and to turn to foodbanks and cut back on getting into rent arrears and, in many heating their homes this Christmas. -

Download Learning Pack 02

BBC Learning English: World Cup English Clubs: 02 Welcome to the second of four BBC World Cup English Club meetings! 1. Welcome the newcomers! Do you remember all your team-mates’ names and at least three details about them? a newcomer = somebody who has just arrived for Introduce a team-mate to the rest of the group and the first time especially to any newcomers to your English Club. If you are a newcomer, introduce yourself! Q. Which team has been most impressive so far? A. I think Argentina and Spain are looking very strong. Q. What do you think of Brazil's performance? A. They weren't at their best. They need to raise their game. (= improve) Q. How do you rate France? A. I think they are getting on a bit. (= they are getting old) 2. The World cup so far… Q. Who do you think is Talk to one another about the World Cup games going to go through in that you have already watched this year. Group A? (= qualify for the next round) Some ideas for questions and answers are on the Q. Who's been the star left. player so far? (= the best player) Page 1 of 5 bbclearningenglish.com © BBC Learning English 2006 World Cup English Clubs Learning Pack 02 BBC Learning English 3. Match commentaries Look at the phrases on the left-hand side of this And Ronaldinho… page. …blocks Kewell's shot Then complete the commentary below: He puts his body in the way of Kewell's shot. …picks out Ronaldo… Beck ham looks up, ready to pass the He spots and passes the ball to Ronaldo. -

Disabled People As Football Fans Introduction

Durham E-Theses Supporting the Fans: Learning-disability, Football Fandom and Social Exclusion SOUTHBY, KRIS How to cite: SOUTHBY, KRIS (2013) Supporting the Fans: Learning-disability, Football Fandom and Social Exclusion, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7004/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Kris Southby Supporting the Fans: Learning-disability, Football Fandom and Social Exclusion In Britain, within the contemporary drive of using sport to tackle the isolation of socially excluded groups, association football (football) fandom has been implicated in many policy documents as a possible site for learning-disabled people to become more socially included. However, whilst there is some evidence of the benefits of playing football for learning-disabled people, there is little evidence to support these claims. Drawing on empirical data from learning-disabled people about their experiences of football fandom and from relevant authorities responsible for facilitating the fandom of learning-disabled people, this thesis provides a critical analysis of the opportunities to tackle social exclusion that football fandom provides learning-disabled people. -

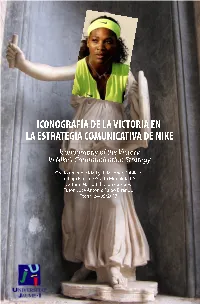

TFG 2017 Taboadacampos M

ICONOGRAFÍA DE LA VICTORIA EN LA ESTRATEGIA COMUNICATIVA DE NIKE Iconography of the Victory in Nike’s Communication Strategy Grado en Publicidad y Relaciones Públicas Trabajo Final de Grado Modalidad A Autora: Marta Taboada Campos Tutor: José Antonio Palao Errando Fecha: 24/05/2017 ICONOGRAFÍA DE LA VICTORIA EN LA ESTRATEGIA COMUNICATIVA DE NIKE RESUMEN Y PALABRAS CLAVE Resumen: Este trabajo propone desvelar la estrategia creativa de Nike, indagando en un aspecto concreto de la misma: la representación visual del mito de la Victoria. A través del análisis iconográfico de sus representaciones visuales durante los últimos 30 años (1985-2015) y de la división cronológica de las etapas clave de su historia publicitaria, hemos llevado a cabo una lectura analítica de su discurso. Dicho análisis ha servido para extrapolar un modelo estratégico válido centrado en el análisis iconográfico. Nike ha mantenido una misma línea estratégica basada en la victoria personal de sus consumidores, instaurando así un estilo y un tono representativos de su identidad corporativa. En primer lugar, Nike fue pionero en el sector de la moda deportiva en utilizar el storytelling como método creativo. La marca entendió la complejidad y la competitividad del mercado y llevó sus productos no sólo al terreno atlético, sino a todo tipo de targets, a través de un discurso social. Este fue el gran logro comunicativo de Nike: transmitir a los consumidores que todo aquel que lo ansíe, puede llegar a ser un gran atleta. En segundo lugar, Nike entendió los comportamientos que se crean alrededor del universo deportivo y de aquellos que lo practican.