2016 Veth Manuel 1142220 Et

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theory of the Beautiful Game: the Unification of European Football

Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 54, No. 3, July 2007 r 2007 The Author Journal compilation r 2007 Scottish Economic Society. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main St, Malden, MA, 02148, USA THEORY OF THE BEAUTIFUL GAME: THE UNIFICATION OF EUROPEAN FOOTBALL John Vroomann Abstract European football is in a spiral of intra-league and inter-league polarization of talent and wealth. The invariance proposition is revisited with adaptations for win- maximizing sportsman owners facing an uncertain Champions League prize. Sportsman and champion effects have driven European football clubs to the edge of insolvency and polarized competition throughout Europe. Revenue revolutions and financial crises of the Big Five leagues are examined and estimates of competitive balance are compared. The European Super League completes the open-market solution after Bosman. A 30-team Super League is proposed based on the National Football League. In football everything is complicated by the presence of the opposite team. FSartre I Introduction The beauty of the world’s game of football lies in the dynamic balance of symbiotic competition. Since the English Premier League (EPL) broke away from the Football League in 1992, the EPL has effectively lost its competitive balance. The rebellion of the EPL coincided with a deeper media revolution as digital and pay-per-view technologies were delivered by satellite platform into the commercial television vacuum created by public television monopolies throughout Europe. EPL broadcast revenues have exploded 40-fold from h22 million in 1992 to h862 million in 2005 (33% CAGR). -

People's Anti-Violence Rallies Foiled Enemies' Plot

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 16 Pages Price 40,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 39th year No.13540 Thursday NOVEMBER 28, 2019 Azar 7, 1398 Rabi’ Al thani 1, 1441 Rouhani promises Iran believes IFFHS Awards: IIDCYA CEO warns to help quake-hit in a strong Faghani best Asian about rise in imported people 2 neighborhood 2 referee of 2019 15 children’s literature 16 Domestic production to save Iran $10b in 2 years People’s anti-violence TEHRAN — Iranian Industry, Mining munications equipment, and $400 million and Trade Minister Reza Rahmani said via indigenizing production of car parts, that relying on domestic production will of which $300 million has been already save $10 billion for the country in the next achieved. two years, IRIB reported. “Today, all available potentials and Speaking in a ceremony on indigeniz- capacities in the country are being used rallies foiled enemies’ plot ing production of telecommunications to materialize the target of domestic equipment on Tuesday, the minister said production and the Ministry of Indus- that of the mentioned $10 billion, some try, Mining and Trade will spare no See page 2 $500 million is predicted to be earned effort in this due”, Rahmani further through domestic production of telecom- emphasized. 4 731 banks, 70 gas stations destroyed in recent unrest: minister TEHRAN — Interior Minister Abdolreza religious centers and burned 307 auto- Rahmani Fazli says 731 banks and 70 gas mobiles and 1076 motorcycles,” he added. -

Match Press Kits

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - 2015/16 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Arena Khimki - Khimki Wednesday 21 October 2015 20.45CET (21.45 local time) PFC CSKA Moskva Group B - Matchday 3 Manchester United FC Last updated 22/02/2016 16:11CET UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE OFFICIAL SPONSORS Previous meetings 2 Match background 4 Squad list 6 Head coach 8 Match officials 9 Fixtures and results 11 Match-by-match lineups 15 Group Standings 17 Team facts 19 Legend 22 1 PFC CSKA Moskva - Manchester United FC Wednesday 21 October 2015 - 20.45CET (21.45 local time) Match press kit Arena Khimki, Khimki Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Owen 29, Scholes 84, Manchester United FC - PFC A. Valencia 90+2; 03/11/2009 GS 3-3 Manchester CSKA Moskva Dzagoev 25, Krasić 31, V. Berezutski 47 PFC CSKA Moskva - Manchester 21/10/2009 GS 0-1 Moscow A. Valencia 86 United FC Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA PFC CSKA Moskva 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 1 3 4 Manchester United FC 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 1 1 0 4 3 PFC CSKA Moskva - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Manchester City FC - PFC CSKA Touré 8; Doumbia 2, 05/11/2014 GS 1-2 Manchester Moskva 34 Doumbia 65, Natcho PFC CSKA Moskva - Manchester 21/10/2014 GS 2-2 Khimki 86 (P); Agüero 29, City FC Milner 38 UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Agüero 3 (P), 20, Manchester City FC - PFC CSKA Negredo 30, 51, 05/11/2013 GS 5-2 Manchester Moskva -

Uefa Europa League

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE - 2018/19 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Sarpsborg Stadium - Sarpsborg Thursday 29 November 2018 21.00CET (21.00 local time) Sarpsborg 08 FF Group I - Matchday 5 Beşiktaş JK Last updated 28/11/2018 04:44CET Match background 2 Legend 4 1 Sarpsborg 08 FF - Beşiktaş JK Thursday 29 November 2018 - 21.00CET (21.00 local time) Match press kit Sarpsborg Stadium, Sarpsborg Match background European colts Sarpsborg are in the thick of the race for qualification from Group I and will eliminate continental thoroughbreds Beşiktaş with victory in Norway on matchday five. • Newcomers to Europe this season, Sarpsborg have already played 12 games in this UEFA Europa League campaign. Having gained their first group stage win at home to Genk on matchday two (3-1), they drew both Scandinavian derbies with Malmö 1-1 and are level on points (and goal difference) with the Swedish side – two behind the front-runners from Belgium. • Beşiktaş currently prop up the group table with four points, having collected just one from their past three fixtures – in a 1-1 draw on matchday four away to Genk, who had beaten them 4-2 in Istanbul a fortnight earlier, inflicting a second successive loss after they had gone down 2-0 at Malmö. A further defeat in Norway will knock out Beşiktaş. Previous meetings • Beşiktaş beat Sarpsborg 3-1 in Istanbul on the visitors' group stage bow, Dutchmen Ryan Babel and Jeremain Lens both finding the net. There had been no previous matches between the two clubs, nor between Sarpsborg and any other Turkish team. -

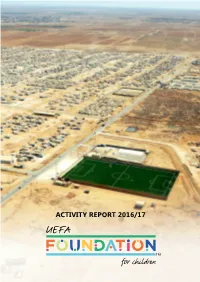

UEFA Foundation for Children Activity Report for 2016/17

ACTIVITY REPORT 2016/17 4 SOMMAIRE THE HEART OF THE FOUNDATION ÉDITORIAUX 6 2016 CALL FOR PROJECTS 12 2017 UEFA FOUNDATION FOR CHILDREN AWARD le besoin, celui de convertir les valeurs Après une année de travail assidu EDITORIAL Tania Baima, Laure N’Singui-Lubanzadio, Cyril Pellevat, Pascal Torres 14 fondamentales de la civilisation euro- et d’objectifs ambitieux, un grand PHOTOS REFUGEES AND DISPLACED PEOPLE American Near East Refugee Aid péenne – la dignité humaine, la solidarité nombre de programmes humanitaires 03 20 27 Armenian Football Federation Barbara Čeferin EDITORIAL CAIS Associação de Solidariedade Social et l’espoir – en occasions d’améliorer et de développement sont aujourd’hui 20 Cancer Fund for Children Éditoriaux Billets de matches Chiffres clés Concordia la vie des enfants. menés par la Fondation dans le monde PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT Coopération Internationale pour les Équilibres Locaux Croatian Football Federation Diogenes entier. Nous continuerons à mobiliser Education for the Children 24 European Football for Development Network FC Barcelona Foundation L’UEFA, dont la Fondation est indépen- l’ensemble de la famille du football – les DISABILITY RESEARCH FedEx Football Federation of Ukraine dante, s’est engagée à lui verser une clubs, les associations nationales et les EDUCATION Football For All in Vietnam Football Union of Russia Another successful year of activities has come In May, the foundation’s board of trustees FundLife International to a close. It wascontribution a highly productive 12 monthsannuelle jusqu’en 2025. sponsorswelcomed four – new dans members, ce therebybut. inUn- simple ballon Icehearts of Finland for the UEFA Foundation for Children, a time creasing its representative nature and plu- 26 IMBEWU Instituto Fazer Acontecer in which we wereEn able outre, to continue des and capitaux de- importants ont peutrality. -

Parliamentary Coalition Collapses

INSIDE:• Profile: Oleksii Ivchenko, chair of Naftohaz — page 3. • Donetsk teen among winners of ballet competition — page 9. • A conversation with historian Roman Serbyn — page 13. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXIVTHE UKRAINIANNo. 28 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JULY 9,W 2006 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine World Cup soccer action Parliamentary coalition collapses Moroz and Azarov are candidates for Rada chair unites people of Ukraine by Zenon Zawada The Our Ukraine bloc had refused to Kyiv Press Bureau give the Socialists the Parliament chair- manship, which it wanted Mr. KYIV – Just two weeks after signing a Poroshenko to occupy in order to coun- parliamentary coalition pact with the Our terbalance Ms. Tymoshenko’s influence Ukraine and Yulia Tymoshenko blocs, as prime minister. Socialist Party of Ukraine leader Eventually, Mr. Moroz publicly relin- Oleksander Moroz betrayed his Orange quished his claim to the post. Revolution partners and formed a de His July 6 turnaround caused a schism facto union with the Party of the Regions within the ranks of his own party as and the Communist Party. National Deputy Yosyp Vinskyi Recognizing that he lacked enough announced he was resigning as the first votes, Our Ukraine National Deputy secretary of the party’s political council. Petro Poroshenko withdrew his candida- Mr. Moroz’s betrayal ruins the demo- cy for the Verkhovna Rada chair during cratic coalition and reveals his intention the Parliament’s July 6 session. to unite with the Party of the Regions, The Socialists then nominated Mr. Mr. Vinskyi alleged. -

Uefa Europa League

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE - 2020/21 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Old Trafford - Manchester Thursday 11 March 2021 18.55CET (17.55 local time) Manchester United FC Round of 16, First leg AC Milan Last updated 09/03/2021 18:11CET Match background 2 Legend 4 1 Manchester United FC - AC Milan Thursday 11 March 2021 - 18.55CET (17.55 local time) Match press kit Old Trafford, Manchester Match background Two former European champions meet in a heavyweight UEFA Europa League contest as Manchester United go head to head with AC Milan in the round of 16. • United competed in the UEFA Champions League during the autumn, but defeats in their final two Group H fixtures left them in third place on nine points behind Paris Saint-Germain and RB Leipzig. They subsequently maintained their perfect record in the UEFA Europa League round of 32 by eliminating Real Sociedad, a 4-0 win in Budapest's Puskás Aréna followed by a goalless draw at Old Trafford. • Milan, who kicked off their European campaign in the UEFA Europa League second qualifying round, qualified for the knockout phase from a tough group comprising LOSC Lille, Sparta Praha and Celtic, leapfrogging the French side on Matchday 6 to take top spot with 13 points. They then knocked out Crvena zvezda in the round of 32 (2-2 a, 1-1 h), an own goal, two penalties and the away goals rule carrying them through. Previous meetings • This is the clubs' first UEFA encounter for 11 years, although they have been drawn against each other five times previously, on every occasion in the European Cup/UEFA Champions League knockout phase. -

Italy Record Biggest Opening Win of European Championships After Own Goal, Immobile and Insigne Down Sloppy Turks

SATURDAY • 12th JUNE 2021 Italy’s forward Lorenzo Insigne (top) and teammates celebrate an own goal by Turkey defender Merih Demiral during today’s EURO 2020 Group A match at the Olympic Stadium in Rome. – AFPPIX Statement of intent Italy record biggest opening win of European Championships after own goal, Immobile and Insigne down sloppy Turks ‘Devils are WAG OF THE DAY Wales hope Euro 2020 fixtures, great even Jessica Melena to emulate results and whiout boys of 2016 standings De Bruyne page 3 page 4 page 7 page 8 2 SATURDAY 12th JUNE 2021 LET THE GAMES BEGIN … A fireworks display is triggered over the Olympic stadium today in Rome as part of the Euro 2020 opening ceremony, prior to the Turkey vs Italy match. – AFPPIX Impressive Azzurri Hosts sends out statement across Europe in tournament’s first game “We played a good match, even in the first and Immobile nodded a cross wide as the hosts TALY kicked off the European half without being able to score. A great team. stretched the Turkish defence. Championship with a convincing 3-0 There was a lot of help from the crowd.” Insigne curled a shot straight at Cakir from victory over Turkey in Group A at Rome’s Goalscorer Insigne added: “Our strength is the edge of the box and Immobile fired into the Stadio Olimpico this morning with Ciro the group; the coach has created a great group keeper’s arms as Italy headed in at the break IImmobile and Lorenzo Insigne on target. in which there are no starters and bench players with 14 attempts to none from Turkey. -

3. All-Time Records 1955-2019

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE STATISTICS HANDBOOK 2019/20 3. ALL-TIME RECORDS 1955-2019 PAGE EUROPEAN CHAMPION CLUBS’ CUP/UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE ALL-TIME CLUB RANKING 1 EUROPEAN CHAMPION CLUBS’ CUP/UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE ALL-TIME TOP PLAYER APPEARANCES 5 EUROPEAN CHAMPION CLUBS’ CUP/UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE ALL-TIME TOP GOALSCORERS 8 NB All statistics in this chapter include qualifying and play-off matches. Pos Club Country Part Titles Pld W D L F A Pts GD ALL-TIME CLUB RANKING 58 FC Salzburg AUT 15 0 62 26 16 20 91 71 68 20 59 SV Werder Bremen GER 9 0 66 27 14 25 109 107 68 2 60 RC Deportivo La Coruña ESP 5 0 62 25 17 20 78 79 67 -1 Pos Club Country Part Titles Pld W D L F A Pts GD 61 FK Austria Wien AUT 19 0 73 25 16 32 100 110 66 -10 1 Real Madrid CF ESP 50 13 437 262 76 99 971 476 600 495 62 HJK Helsinki FIN 20 0 72 26 12 34 91 112 64 -21 2 FC Bayern München GER 36 5 347 201 72 74 705 347 474 358 63 Tottenham Hotspur ENG 6 0 53 25 10 18 108 79 60 29 3 FC Barcelona ESP 30 5 316 187 72 57 629 302 446 327 64 R. Standard de Liège BEL 14 0 58 25 10 23 87 73 60 14 4 Manchester United FC ENG 28 3 279 154 66 59 506 264 374 242 65 Sevilla FC ESP 7 0 52 24 12 16 86 73 60 13 5 Juventus ITA 34 2 277 140 69 68 439 268 349 171 66 SSC Napoli ITA 9 0 50 22 14 14 78 61 58 17 6 AC Milan ITA 28 7 249 125 64 60 416 231 314 185 67 FC Girondins de Bordeaux FRA 7 0 50 21 16 13 54 54 58 0 7 Liverpool FC ENG 24 6 215 121 47 47 406 192 289 214 68 FC Sheriff Tiraspol MDA 17 0 68 22 14 32 66 74 58 -8 8 SL Benfica POR 39 2 258 114 59 85 416 299 287 117 69 FC Dinamo 1948 ROU -

Uefa Europa League

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE - 2016/17 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Şükrü Saracoğlu - Istanbul Thursday 3 November 2016 19.00CET (21.00 local time) Fenerbahçe SK Group A - Matchday 4 Manchester United FC Last updated 08/08/2019 23:36CET Previous meetings 2 Match background 5 Team facts 7 Squad list 9 Fixtures and results 11 Match-by-match lineups 12 Match officials 14 Legend 15 1 Fenerbahçe SK - Manchester United FC Thursday 3 November 2016 - 19.00CET (21.00 local time) Match press kit Şükrü Saracoğlu, Istanbul Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA Europa League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Pogba 31 (P), 45+1, Manchester United FC - 20/10/2016 GS 4-1 Manchester Martial 34 (P), Lingard Fenerbahçe SK 48; Van Persie 83 UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Fenerbahçe SK - Manchester Tuncay Şanlı 47, 62, 08/12/2004 GS 3-0 Istanbul United FC 90+1 Giggs 7, Rooney 17, 28, 54, Van Nistelrooy Manchester United FC - 28/09/2004 GS 6-2 Manchester 78, Bellion 81; Mert Fenerbahçe SK Nobre 46, Tuncay Şanlı 59 UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Manchester United FC - 30/10/1996 GS 0-1 Manchester Bolić 79 Fenerbahçe SK Fenerbahçe SK - Manchester Beckham 55, Cantona 16/10/1996 GS 0-2 Istanbul United FC 60 Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA Fenerbahçe SK 2 1 0 1 3 1 0 2 0 0 0 0 5 2 0 3 7 12 Manchester United FC 3 2 0 1 2 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 5 3 0 2 12 7 Fenerbahçe SK - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers 2-0 -

European Qualifiers

EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS - 2014/16 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Ernst-Happel-Stadion - Vienna Saturday 15 November 2014 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Austria Group G - Matchday -9 Russia Last updated 12/07/2021 15:38CET Official Partners of UEFA EURO 2020 Previous meetings 2 Match background 3 Squad list 4 Head coach 6 Match officials 7 Competition facts 8 Match-by-match lineups 9 Team facts 11 Legend 13 1 Austria - Russia Saturday 15 November 2014 - 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Match press kit Ernst-Happel-Stadion, Vienna Previous meetings Head to Head FIFA World Cup Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached 06/09/1989 QR (GS) Austria - USSR 0-0 Vienna Mykhailychenko 47, 19/10/1988 QR (GS) USSR - Austria 2-0 Kyiv Zavarov 68 1968 UEFA European Championship Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Austria - USSR Football 15/10/1967 PR (GS) 1-0 Vienna Grausam 50 Federation Malofeev 25, Byshovets 36, USSR Football Federation - 11/06/1967 PR (GS) 4-3 Moscow Chislenko 43, Austria Streltsov 80; Hof 38, Wolny 54, Siber 71 FIFA World Cup Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached 11/06/1958 GS-FT USSR - Austria 2-0 Boras Ilyin 15, Ivanov 63 Final Qualifying Total tournament Home Away Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA EURO Austria 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 - - - - 2 1 0 1 4 4 Russia 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 - - - - 2 1 0 1 4 4 FIFA* Austria 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 3 0 1 2 0 4 Russia 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 3 2 1 0 4 0 Friendlies Austria - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 3 3 5 9 14 Russia - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 5 3 3 14 9 Total Austria 2 1 1 0 2 0 0 2 1 0 0 1 16 4 4 8 13 22 Russia 2 2 0 0 2 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 16 8 4 4 22 13 * FIFA World Cup/FIFA Confederations Cup 2 Austria - Russia Saturday 15 November 2014 - 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Match press kit Ernst-Happel-Stadion, Vienna Match background Austria are taking on Russia for the first time since the end of the Soviet Union in UEFA EURO 2016 qualifying Group G, having failed to score in two previous friendly encounters. -

First Division Clubs in Europe 2014/15

CONTENTS | TABLE DES MATIÈRES | INHALTSVERZEICHNIS UEFA CLUB COMPETITIONS Calendar – 2014/15 UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE 3 Calendar – 2014/15 UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE 4 UEFA MEMBER ASSOCIATIONS Albania | Albanie | Albanien 5 Andorra | Andorre | Andorra 7 Armenia | Arménie | Armenien 9 Austria | Autriche | Österreich 11 Azerbaijan | Azerbaïdjan | Aserbaidschan 13 Belarus | Belarus | Belarus 15 Belgium | Belgique | Belgien 17 Bosnia and Herzegovina | Bosnie-Herzégovine | Bosnien-Herzegowina 19 Bulgaria | Bulgarie | Bulgarien 21 Croatia | Croatie | Kroatien 23 Cyprus | Chypre | Zypern 25 Czech Republic | République tchèque | Tschechische Republik 27 Denmark | Danemark | Dänemark 29 England | Angleterre | England 31 Estonia | Estonie | Estland 33 Faroe Islands | Îles Féroé | Färöer-Inseln 35 Finland | Finlande | Finnland 37 France | France | Frankreich 39 Georgia | Géorgie | Georgien 41 Germany | Allemagne | Deutschland 43 Gibraltar / Gibraltar / Gibraltar 45 Greece | Grèce | Griechenland 47 Hungary | Hongrie | Ungarn 49 Iceland | Islande | Island 51 Israel | Israël | Israel 53 Italy | Italie | Italien 55 Kazakhstan | Kazakhstan | Kasachstan 57 Latvia | Lettonie | Lettland 59 Liechtenstein | Liechtenstein | Liechtenstein 61 Lithuania | Lituanie | Litauen 63 Luxembourg | Luxembourg | Luxemburg 65 Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia | ARY de Macédoine | EJR Mazedonien 67 Malta | Malte | Malta 69 Moldova | Moldavie | Moldawien 71 Montenegro | Monténégro | Montenegro 73 Netherlands | Pays-Bas | Niederlande 75 Northern Ireland | Irlande du Nord | Nordirland