Disabled People As Football Fans Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Veth Manuel 1142220 Et

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Selling the People's Game Football's transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor State Veth, Karl Manuel Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 Selling the People’s Game: Football's Transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor States K. -

Football, Nationalism and the Chants of Palestinian Resistance in Jordan

“Allah! Wehdat! Al-Quds Arabiya!”: Football, Nationalism and the chants of Palestinian Resistance in Jordan by Joshua MacKenzie B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2010 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Joshua MacKenzie 2015 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2015 Approval Name: Joshua MacKenzie Degree: Master of Arts (History) Title: “Allah! Wehdat! Al-Quds Arabiya!”: Football, Nationalism and the Chants of Palestinian Resistance in Jordan Examining Committee: Chair: Mary-Ellen Kelm Associate Professor Paul Sedra Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Thomas Kuehn Supervisor Associate Professor Derryl MacLean Supervisor Associate Professor Adel Iskandar External Examiner Assistant Professor School of Communication Simon Fraser University Date Defended/Approved: November 27, 2015 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract After the Jordanian Civil War in 1970—which saw the Jordanian army defeat Palestinian guerrillas, the death of thousands of Palestinians living in Jordan and the exile of Palestinian political organizations and leaders from refugee camps—Palestinians in Jordan became politically and socially marginalized. Despite these marginalizations, Palestinians in Jordan always had access to sport. This thesis will examine how the football club, al-Wehdat, plays a role in creating and establishing identity and nationalism for Palestinians in Jordan. By using oral history, I move beyond the narrative of a homogenous Palestinian identity and demonstrate the complexities of Palestinian identities. Moreover, utilizing oral history in my thesis challenges the notion of football being cathartic, and demonstrates how al-Wehdat fans are able to: A) manoeuvre within the stadium, despite being under constant surveillance, B) to continue to use al-Wehdat as a political platform, predominantly through their chants, and C) to develop Palestinian identity and nationalism in Jordan. -

Distribution List Page - 1

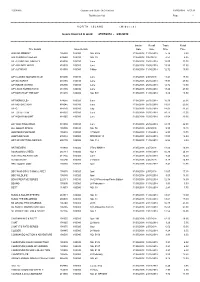

R56891A Gordon and Gotch (NZ) Limited 29/05/2018 8:57:12 Distribution List Page - 1 =========================================================================================================================================================== N O R T H I S L A N D ( M i d w e e k ) Issues invoiced in week 27/05/2018 - 2/06/2018 =========================================================================================================================================================== Invoice Recall Trade Retail Title Details Issue Details Date Date Price Price 2000 AD WEEKLY 105030 100080 NO. 2075 31/05/2018 11/06/2018 5.74 8.80 500 SUDOKU PUZZLES 239580 100010 NO. 39 31/05/2018 9/07/2018 4.53 6.95 A/F AEROPLANE MNTHLY 818005 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 15.00 23.00 A/F AIRLINER WRLD 818020 100020 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 15.59 23.90 A/F AUTOCAR 818030 100080 9 May 31/05/2018 11/06/2018 12.72 19.50 A/F CLASSIC MOTORCYCLE 915600 100010 June 31/05/2018 2/07/2018 11.41 17.50 A/F GUITARIST 818155 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 17.93 27.50 A/F INSIDE UNITED 896390 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 12.72 19.50 A/F LINUX FORMAT DVD 818185 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 18.20 27.90 A/F MATCH OF THE DAY 818215 100080 NO. 504 31/05/2018 11/06/2018 8.80 13.50 A/F MONOCLE> 874655 100020 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 16.30 25.00 A/F MOTORSPORT 818245 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 13.63 20.90 A/F Q 818270 100010 July 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 14.02 21.50 A/F TOTAL FILM 818335 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 10.11 15.50 A/F WOMAN&HOME 818365 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 13.04 20.00 A/F YACHTING WRLD 818380 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 14.35 22.00 ALL ABOUT SPACE 105505 100010 NO. -

ABC Consumer Magazine Concurrent Release - Dec 2007 This Page Is Intentionally Blank Section 1

December 2007 Industry agreed measurement CONSUMER MAGAZINES CONCURRENT RELEASE This page is intentionally blank Contents Section Contents Page No 01 ABC Top 100 Actively Purchased Magazines (UK/RoI) 05 02 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 09 03 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution (UK/RoI) 13 04 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Circulation/Distribution Increases/Decreases (UK/RoI) 17 05 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Actively Purchased Increases/Decreases (UK/RoI) 21 06 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Newstrade and Single Copy Sales (UK/RoI) 25 07 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Single Copy Subscription Sales (UK/RoI) 29 08 ABC Market Sectors - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 33 09 ABC Market Sectors - Percentage Change 37 10 ABC Trend Data - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution by title within Market Sector 41 11 ABC Market Sector Circulation/Distribution Analysis 61 12 ABC Publishers and their Publications 93 13 ABC Alphabetical Title Listing 115 14 ABC Group Certificates Ranked by Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 131 15 ABC Group Certificates and their Components 133 16 ABC Debut Titles 139 17 ABC Issue Variance Report 143 Notes Magazines Included in this Report Inclusion in this report is optional and includes those magazines which have submitted their circulation/distribution figures by the deadline. Circulation/Distribution In this report no distinction is made between Circulation and Distribution in tables which include a Total Average Net figure. Where the Monitored Free Distribution element of a title’s claimed certified copies is more than 80% of the Total Average Net, a Certificate of Distribution has been issued. -

1 a Few Other Things That Kill a Relationship and Totally Piss You Off Is

#1 A few other things that kill a relationship and totally piss you off is when your partner is always on the computer looking at porno or talking to other woman on webcam then hurrying to turn off the computer or switch to another site when you walk in the room also when they are quick to answer their mobile phone and tell you it was the wrong number or not tell you who it was. #2 First thing I get up in the morning I hit a key and start it up! I am a bonifide computer junkie! I wasn't always ,but ever since I got a computer a year ago and learned how to use one it is my life it seems. #3 Hello! my dear! / I am a pretty girl from Russia and very much want to meet you. / I am very optimistic but within reasonable limits. But still there is a lack of one person in my fate. / That is why I'm here. I am waiting for my only man to come to my life. Doors to my soul are open for him. / Look at my pictures: http://lavdate.ru/?vu I will be waiting for you. #4 And you can do it to your conscience You can do it all the time You can do it with a vengeance In the morning after nine But you know You'll always be waiting Always be waiting For someone else to call #5 The usual diversion tactic, the only problem are the touts. What about the false companies set up by the likes of Seb Coe and Jonathon Edwards? Six figure cheques written out for the usual s**t, `consultancy fees`. -

Dirty Secrets of the P10

£1.20 Weekend edition Saturday/Sunday December 2-3 2017 Morning Star Incorporating the Daily Worker For peace and socialism www.morningstaronline.co.uk DIRTY SECRETS OF THE P10 As Tories cut benefi ts across Britain for festive season, people are protesting for the ending of Theresa May’s disastrous universal credit mess UNITE RALLIES TO STOP GRINCH RUINING XMAS by Peter Lazenby benefi t cuts and delayed payments have been driven to using foodbanks to survive. CHRISTMAS has been cancelled for The government has admitted that hundreds of thousands of families the universal credit claimants’ hel- claiming universal credit, but dem- pline will be closed for most of the onstrators up and down the country Christmas period, making life even will take to the streets today to more diffi cult for those needing demand action. advice and emergency help. Trade unionists and campaigners Many activists will run town-cen- will turn out in more than 70 towns tre stalls today to provide some of and cities across Britain, accusing the current half a million victims of the government of “abolishing Christ- the scheme with help and advice. mas” for victims of its benefi ts fi asco. Unite Community head Liane The day of action, organised by Groves said: “Despite knowing that Unite Community — part of Britain’s universal credit causes serious prob- biggest trade union — is aimed at lems for those claiming it, the gov- putting pressure on the government ernment is ploughing ahead regard- to “stop and fi x” universal credit less while claimants are descending before even more families are forced into debt, relying on foodbanks and to turn to foodbanks and cut back on getting into rent arrears and, in many heating their homes this Christmas. -

Download Learning Pack 02

BBC Learning English: World Cup English Clubs: 02 Welcome to the second of four BBC World Cup English Club meetings! 1. Welcome the newcomers! Do you remember all your team-mates’ names and at least three details about them? a newcomer = somebody who has just arrived for Introduce a team-mate to the rest of the group and the first time especially to any newcomers to your English Club. If you are a newcomer, introduce yourself! Q. Which team has been most impressive so far? A. I think Argentina and Spain are looking very strong. Q. What do you think of Brazil's performance? A. They weren't at their best. They need to raise their game. (= improve) Q. How do you rate France? A. I think they are getting on a bit. (= they are getting old) 2. The World cup so far… Q. Who do you think is Talk to one another about the World Cup games going to go through in that you have already watched this year. Group A? (= qualify for the next round) Some ideas for questions and answers are on the Q. Who's been the star left. player so far? (= the best player) Page 1 of 5 bbclearningenglish.com © BBC Learning English 2006 World Cup English Clubs Learning Pack 02 BBC Learning English 3. Match commentaries Look at the phrases on the left-hand side of this And Ronaldinho… page. …blocks Kewell's shot Then complete the commentary below: He puts his body in the way of Kewell's shot. …picks out Ronaldo… Beck ham looks up, ready to pass the He spots and passes the ball to Ronaldo. -

Developments in Federal Search and Seizure Law

FEDERAL PUBLIC DEFENDER DISTRICT OF OREGON LISA C. HAY Federal Public Defender Oliver W. Loewy STEPHEN R. SADY 101 SW Main Street, Suite 1700 Elizabeth G. Daily Chief Deputy Defender Portland, OR 97204 Conor Huseby Gerald M. Needham Robert Hamilton Thomas J. Hester 503-326-2123 / Fax: 503-326-5524 Bryan Francesconi Ruben L. Iñiguez Ryan Costello Anthony D. Bornstein Branch Offices: Irina Hughes▲ Susan Russell Kurt D. Hermansen▲ Francesca Freccero 859 Willamette Street 15 Newtown Street Devin Huseby + C. Renée Manes Suite 200 Medford, OR 97501 Kimberly-Claire E. Seymour▲ Nell Brown Eugene, OR 97401 541-776-3630 Jessica Snyder Kristina Hellman 541-465-6937 Fax: 541-776-3624 Cassidy R. Rice Fidel Cassino-DuCloux Fax: 541-465-6975 Alison M. Clark In Memoriam Brian Butler + Nancy Bergeson Thomas E. Price 1951 – 2009 Michelle Sweet Mark Ahlemeyer ▲ Eugene Office Susan Wilk + Medford Office Research /Writing Attorney DEVELOPMENTS IN FEDERAL SEARCH AND SEIZURE LAW Stephen R. Sady Chief Deputy Federal Public Defender October 2020 Update Madeleine Rogers Law Clerk TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 B. What Constitutes A Search? ............................................................................................ 3 C. What Constitutes A Seizure? ......................................................................................... 14 D. Reasonable Expectation of Privacy .............................................................................. -

03 Prenumerata 2010.Indd

Ośrodek Szkoleniowo -Integracyjny Kolportera w Smardzewicach nad Zalewem Sulejowskim Ośrodek Szkoleniowo-Integracyjny Kolportera w Smardzewicach k/Tomaszowa Mazowieckiego, nad Zalewem Sulejowskim to idealne miejsce do przeprowadzenia wszelkiego rodzaju szkoleń, konferencji, seminariów, imprez integracyjnych, wczasów i rodzinnych imprez okolicznościowych. nasze atuty Dysponujemy zapleczem szkoleniowym i komfortową bazą hotelową. Naszym głównym atutem jest niepowtarzalna, domowa kuchnia! Pobyt naszym gościom umila profesjonalna obsługa. wspaniała okolica Malownicze jezioro, sosnowe lasy, cisza, krystalicznie czyste powietrze, tworzą znakomite warunki do nauki i wypoczynku. dogodna lokalizacja - Tomaszów Mazowiecki 7 km - Łódź – 57 km - Warszawa – 117 km - Katowice – 170 km 97-213 Smardzewice, ul. Klonowa 14 Zapraszamy tel. (+4844) 710 86 81, 510 031 715 e-mail: [email protected] Szanowni Państwo! Historia Kolportera zaczęła się przed 20 laty – w maju 1990 r., od powstania Przedsiębiorstwa Wielobranżowego – Zakładu Kolportażu Książki i Prasy „Kolporter”. W ciągu kilku lat stworzyliśmy jedną z najbardziej dynamicznych organizacji gospodarczych w Polsce – grupę kapitałową, która dzięki profilowi działalności wchodzących w jej skład spółek zapewnia kompleksową obsługę nie tylko dużych firm i sieci handlowych, lecz także pojedynczych punktów sprzedaży detalicznej. W skład Grupy Kapitałowej Kolporter wchodzą: Kolporter DP – największy i najbardziej dynamiczny dystrybutor prasy i książek, posiada 17 oddziałów terenowych zlokalizowanych w największych miastach wojewódzkich i powiatowych. Firma obsługuje ponad 49% rynku dystrybucji prasy, rozprowadza około 5000 tytułów polskich i zagranicznych do ponad 27 tysięcy punktów sprzedaży detalicznej i 12.000 prenumeratorów – firm, banków, urzędów, przedsiębiorstw, instytucji państwowych i samorządowych. Grzegorz Fibakiewicz Firma kurierska K-EX (dawniej Kolporter Express) świadczy usługi kurierskie Prezes Zarządu Kolportera DP Sp. z o.o. dla firm i instytucji. -

The Cultural Practice of Localising Mediated Sports Music

Kaj Ahlsved THE CULTURAL PRACTICE OF LOCALISING MEDIateD SPORts MUSIC The crowd gathers. Hellos with friends and familiar faces are exchanged before I make my way to my familiar seat. The latest news is discussed with those sit- ting next to me: who is injured, who is going to win the game for us, and do we have a good referee today? Someone is munching on a grilled sausage; another is saving it for half time. A third sips his coffee while children happily eat their ice cream. The friend to my left wears long johns in July, the friend to my right usually arrives late carrying his lunch, a plate of kebab. A popular song plays in the background, flags are waving in the wind, and the sun shines over the local sporting event. Suddenly, a march blares from the PA system and in the blink of an eye the focus of the crowd shifts towards the pitch. The crowd claps along to the instrumental German military march Alte Kameraden while the home and away teams walk on to the pitch. The supporter group announces its presence by bursting into one of their familiar chants. It’s game time in Jakobstad/Pietarsaari. The above example describes my personal routine of going to an FF Jaro1 football game at Keskuskenttä in Pietarsaari, Finland. This routine is repeated nearly once a week during football season, only the weather differs from game to game. From a cultural and musicological standpoint, what is interesting about this scenario is the fact that a German instrumental military march, written by 1 From now on simply Jaro. -

Sons of the Mother

SONS OF THE MOTHER Synopsis Two brothers are tied up in the garage by their father to help them kick a deadly habit; but the drug they call 'the mother' is stronger than love. Cast List Andy } Brothers in their twenties Darren } Dad Mum (Dead) 1 SONS OF THE MOTHER Act One Two brothers are tied up in a shed or garage. Depending on budget, this loving restraint could be elaborate steampunk machinery or wooden chairs with rope bindings. The boys are fixed in one position to begin but, as the play unfolds, this ‘apparatus of cruel kindness’ is upgraded, allowing them to sit/stand and lie down. They may eventually be able to swing, slide and see-saw around the equipment; while still bound hand and foot to it. They are suffering the ‘fluey symptoms’ of drug withdrawal. (Some of their dialogue is stylised to sound like moans and groans.) Darkness. ANDY and DARREN: Born. Born. Lights up. ANDY: When were you born? DARREN: 28th February, 1988. ANDY: Bonnie. Blithe. It was a Sunday. Where were you born? DARREN: Canterbury: where the tale begins. No, Glastonbury: where the story starts. Hang on. Was it Stonehenge, or Penge? Olympia or Mount Olympus? Where does it look like I come from? ANDY: You must remember exactly. We need to know if we’re dealing with comedy or tragedy. Morecambe, Bognor, Torquay; born there and you’ll be laughing. Dunblane, Hungerford, Enniskillen; it’s going to end in tears. DARREN: Penge. It began here. ANDY: Actually, it’s Annerley, isn’t it? Where Puff the magic dragon lives. -

Seven Nation Army Med Ett Riff Som Sjungs Till Fotboll

Seven Nation Army Med ett riff som sjungs till fotboll Patrik Sandgren Fotboll och musik kan på samma gång uppfat- med den spridda och i åtminstone europe- tas som en lek (jfr Huizinga 1945).1 På mot- iska supportersammanhang numera klassiska svarande sätt leker i någon mån musikerna i ”Triumfmarschen”, ur italienska nationalope- ett band eller sångarna i en kör. Ibland befin- ran Aida av Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) med ner de sig på olika kunskapsnivå och agerar premiär i Kairo 1871.3 Följaktligen använder därför på skilda sätt utifrån regler och norm- fotbollspubliken musik som delar liknande givande mönster. Under sådana betingelser formspråk och funktioner som nämnda hyll- kan också det musikaliskt impulsiva hända ningssånger. och utvecklas. Supportrarnas sånger kan antingen trallas Sambanden mellan fotboll och musik är utan ord, eller sjungas tillsammans med nya intressanta att studera, inte minst för att äm- eller modifierade texter. Själva melodierna net utifrån musikvetenskapliga och musiket- kännetecknas ofta av tonupprepningar, litet nologiska perspektiv är tämligen marginellt tonomfång som sällan överstiger en kvint, genomgånget, också beträffande svenska för- och små terssprång (Kopiez 1990:360ff; hållanden. Säkert kan de musikaliska uttryck 1992:227f). Reinhard Kopiez, som särskilt som förknippas med fotboll många gånger undersökt vad tyska supportrar sjunger, me- uppfattas som efterhärmade, fragmentariska nar att melodistrukturerna likväl är ordnade och inte konstfärdiga nog att undersökas efter ”archaischen Melodiebildungsprinzi- närmare. Insatt i en kontext med hänsyn till pien” (1990:362). Sångkören på läktarna kan samhällsrelevans och historiska förlopp torde uppstå närmast spontant och sången utföras emellertid temat erbjuda mer att utforska. mer eller mindre unisont.