No. 10 HELGA DICKOW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Introduction Abdel Ghaffar M. Ahmed and Hassan A. Abdel Ati Human Adaptation in East African Drylands:The Dilemma of Concepts and Approaches Leif Manger From Adaptation to Marginalization:The Political Ecology of Subsistence Crisis Among the Hadendawa Pastoralists of Eastern Sudan Omer Abdalla Egeimi External Pressures on Indigenous Resource Management Systems: A Case from the Red Sea Area, Eastern Sudan Hassan A. Abdel Ati Agriculture and Pastoralism in Karamoja: Competing or Complementary Forms of Resource Use? Frank Emmanuel Muhereza Management of Aridity:Water Conservation and Procurement in Dar Hamar, Western Sudan Mustafa Babiker Subsistence Economy, Environmental Awareness and Resource Management in Um Kaddada Province, Northern Darfur State Munzoul Abdalla Munzoul Economic Strategies of Diversification Among the Sedentary 'afar of Wahdes, North Eastern Ethiopia Assefa Tewodros Management of Scarce Resources: Dryland Pastoralism Among the Zaghawa of Chad and the Crisis of the Eighties Sharif Harir Resource Management in the Eritrean Drylands: Case Studies From the Central Highlands and the Eastern Lowlands Mohamed Kheir, Adugna Haile and Wolde-Amlak Araia Survival Strategies in the Ethiopian Drylands: The Case of the Afar Pastoralists of the Awash Valley Ali Said Yesuf State Policy and Pastoral Production Systems: The Integrated Land Use Plan of Rawashda Forest, Eastern Sudan Salah El Shazali Ibrahim The Importance of Forest Resource Management in Eastern Sudan: The Case of El Rawashda and Wad Kabo Forest Reserves -

Chad – Towards Democratisation Or Petro-Dictatorship?

DISCUSSION PAPER 29 Hans Eriksson and Björn Hagströmer CHAD – TOWARDS DEMOCRATISATION OR PETRO-DICTATORSHIP? Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, Uppsala 2005 Indexing terms Democratisation Petroleum extraction Governance Political development Economic and social development Chad The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Nordiska Afrikainstitutet Language checking: Elaine Almén ISSN 1104-8417 ISBN printed version 91-7106-549-0 ISBN electronic version 91-7106-550-4 © the authors and Nordiska Afrikainstitutet Printed in Sweden by Intellecta Docusys AB, Västra Frölunda 2005 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................5 2. Conceptual framework ...................................................................................7 2.1 Rebuilding state authorities, respect for state institutions and rule of law in collapsed states..................................................................7 2.2 Managing oil wealth for development and poverty reduction................11 2.3 External influence in natural resource rich states...................................19 3. State and politics in Africa: Chad’s democratisation process ..........................25 3.1 Historical background ..........................................................................25 3.2 Political development and democratisation...........................................26 3.3 Struggle for a real and lasting peace ......................................................37 -

Prosecuting Hissene Habre: Establishing a Factual Background of the Rise, Rule and Fall of Hissene Habre

PROSECUTING HISSENE HABRE: ESTABLISHING A FACTUAL BACKGROUND OF THE RISE, RULE AND FALL OF HISSENE HABRE Bridget Rhinehart* Nearly 25 years after the fall of Hissène Habré and his regime, the fear, oppression and widespread violations of human rights endured by Chadians from 1982 to 1990 may now come to light. This paper contextualizes the judicial proceedings against Hissène Habré through the pre- and post-colonial landscape that shaped to Habré’s rise to power and by establishing a relevant factual background of the events that took place and alleged crimes committed from 1982 to 1990 under the Hissène Habré regime. 1. Chad – a Country Overview Chad is a landlocked central African nation home to just over 11 million people.1 The capital of Chad, N’Djamena, is located in Central to Southwest Chad and is home to more than one million people, leaving the remainder of Chad largely rural.2 The official * Program Manager in humanitarian response at Save the Children USA, Washington, D.C. (U.S.A.). This paper was written during a research assistantship at the Arcadia Center for East African Studies in Arusha (United Republic of Tanzania) in 2011 and recently updated for the purpose of this publication. 1 United Nations, “World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision,” Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat (http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/index.htm). 2 United Nations, “Chad,” United Nations Statistics Division Country Profiles (http://data.un.org/CountryProfile.aspx?crName=CHAD). A.A. YUSUF (ed.), African Yearbook of International Law, 343-374. -

THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC and Small Arms Survey by Eric G

SMALL ARMS: A REGIONAL TINDERBOX A REGIONAL ARMS: SMALL AND REPUBLIC AFRICAN THE CENTRAL Small Arms Survey By Eric G. Berman with Louisa N. Lombard Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland p +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 e [email protected] w www.smallarmssurvey.org THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND SMALL ARMS A REGIONAL TINDERBOX ‘ The Central African Republic and Small Arms is the most thorough and carefully researched G. Eric By Berman with Louisa N. Lombard report on the volume, origins, and distribution of small arms in any African state. But it goes beyond the focus on small arms. It also provides a much-needed backdrop to the complicated political convulsions that have transformed CAR into a regional tinderbox. There is no better source for anyone interested in putting the ongoing crisis in its proper context.’ —Dr René Lemarchand Emeritus Professor, University of Florida and author of The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa ’The Central African Republic, surrounded by warring parties in Sudan, Chad, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, lies on the fault line between the international community’s commitment to disarmament and the tendency for African conflicts to draw in their neighbours. The Central African Republic and Small Arms unlocks the secrets of the breakdown of state capacity in a little-known but pivotal state in the heart of Africa. It also offers important new insight to options for policy-makers and concerned organizations to promote peace in complex situations.’ —Professor William Reno Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University Photo: A mutineer during the military unrest of May 1996. -

Tcd Str Hno2017 Fr 20161216.Pdf

APERÇU DES 2017 BESOINS HUMANITAIRES PERSONNES DANS LE BESOIN 4,7M NOV 2016 TCHAD OCHA/Naomi Frerotte Ce document est élaboré au nom de l'Equipe Humanitaire Pays et de ses partenaires. Ce document présente la vision des crises partagée par l'Equipe Humanitaire Pays, y compris les besoins humanitaires les plus pressants et le nombre estimé de personnes ayant besoin d'assistance. Il constitue une base factuelle consolidée et contribue à informer la planification stratégique conjointe de réponse. Les appellations employées dans le rapport et la présentation des différents supports n'impliquent pas d'opinion quelconque de la part du Secrétariat de l'Organisation des Nations Unies concernant le statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni de la délimitation de ses frontières ou limites géographiques. www.unocha.org/tchad www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/chad @OCHAChad PARTIE I : PARTIE I : RÉSUMÉ Besoins humanitaires et chiffres clés Impact de la crise Personnes dans le besoin Sévérité des besoins 03 PERSONNESPARTIE DANS LEI : BESOIN Personnes dans le besoin par Sites et Camps de déplacement catégorie (en milliers) M Site de retournés 4,7 Population Camp de réfugiés Ressortissants locale de pays tiers Sites/lieux de déplacement interne EGYPTE Personnes xx déplacées Réfugiés MAS supérieur à 2% internes Retournés Phases du Cadre Harmonisé (période projetée, juin-août 2017) LIBYE Minimale (phase 1) Sous pression (phase 2) Crise (phase 3) TIBESTI 13 NIGER ENNEDI OUEST 35 ENNEDI EST BORKOU 82 04 -

Report of the Joint Human Rights Promotion Mission To

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Commission Africaine des Droits de l’Homme & des African Commission on Human & Peoples’ Peuples Rights No. 31 Bijilo Annex Lay-out, Kombo North District, Western Region, P. O. Box 673, Banjul, The Gambia Tel: (220) 441 05 05 /441 05 06, Fax: (220) 441 05 04 E-mail: [email protected]; Web www.achpr.org REPORT OF THE JOINT HUMAN RIGHTS PROMOTION MISSION TO THE REPUBLIC OF CHAD 11 - 19 MARCH 2013 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the Commission) is grateful to the Government of the Republic of Chad for kindly hosting, from 11 to 19 March 2013, a joint human rights promotion mission undertaken by a delegation of the Commission. The Commission expresses its sincere gratitude to the country’s highest authorities for providing the delegation with the necessary facilities and personnel for the smooth conduct of the mission. The Commission expresses its appreciation to Ms Amina Kodjiyana, Minister for Human Rights and the Promotion of Fundamental Freedoms, and her advisers for their key role in organising the various meetings and for ensuring the success of the mission. 2 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AfDB : African Development Bank APRM : African Peer Review Mechanism AU : African Union BEPC : Secondary School Leaving Certificate CENI : Independent National Electoral Commission CNARR : National Commission for the Reception and Reintegration of Refugees and Returnees COBAC : Central African Banking Commission CSO : Civil Society Organisation DSG : Deputy Secretary-General -

Consolidated Appeal Mid-Year Review 2013+

CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ A tree provides shelter for a meeting with a community of returnees in Borota, Ouaddai Region. Pierre Peron / OCHA CHAD Consolidated Appeal Mid-Year Review 2013+ CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ Participants in 2013 Consolidated Appeal A AFFAIDS, ACTED, Action Contre la Faim, Avocats sans Frontières, C CARE International, Catholic Relief Services, COOPI, NGO Coordination Committee in Chad, CSSI E ESMS F Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations I International Medical Corps UK, Intermon Oxfam, International Organization for Migration, INTERSOS, International Aid Services J Jesuit Relief Services, JEDM, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS M MERLIN O Oxfam Great Britain, Organisation Humanitaire et Développement P Première Urgence – Aide Médicale Internationale S Solidarités International U United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, United Nations Development Programme, UNAD, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations Children’s Fund W World Food Programme, World Health Organization. Please note that appeals are revised regularly. The latest version of this document is available on http://unocha.org/cap. Full project details, continually updated, can be viewed, downloaded and printed from http://fts.unocha.org. CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ TABLE OF CONTENTS REFERENCE MAP ................................................................................................................................ -

Jeremy Mcmaster Rich

Jeremy McMaster Rich Associate Professor, Department of Social Sciences Marywood University 2300 Adams Avenue, Scranton, PA 18509 570-348-6211 extension 2617 [email protected] EDUCATION Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. Ph.D., History, June 2002 Thesis: “Eating Disorders: A Social History of Food Supply and Consumption in Colonial Libreville, 1840-1960.” Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Phyllis Martin Major Field: African history. Minor Fields: Modern West European history, African Studies Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. M.A., History, December 1994 University of Chicago, Chicago, IL. B.A. with Honors, History, June 1993 Dean’s List 1990-1991, 1992-1993 TEACHING Marywood University, Scranton, PA. Associate Professor, Dept. of Social Sciences, 2011- Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN. Associate Professor, Dept. of History, 2007-2011 Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN. Assistant Professor, Dept. of History, 2006-2007 University of Maine at Machias, Machias, ME. Assistant Professor, Dept. of History, 2005-2006 Cabrini College, Radnor, PA. Assistant Professor (term contract), Dept. of History, 2002-2004 Colby College, Waterville, ME. Visiting Instructor, Dept. of History, 2001-2002 CLASSES TAUGHT African History survey, African-American History survey (2 semesters), Atlantic Slave Trade, Christianity in Modern Africa (online and on-site), College Success, Contemporary Africa, France and the Middle East, Gender in Modern Africa, Global Environmental History in the Twentieth Century, Historical Methods (graduate course only), Historiography, Modern Middle East History, US History survey to 1877 and 1877-present (2 semesters), Women in Modern Africa (online and on-site courses), Twentieth Century Global History, World History survey to 1500 and 1500 to present (2 semesters, distance and on-site courses) BOOKS With Douglas Yates. -

Régions De Logone Occidental Et Logone Oriental

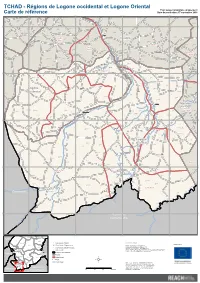

TCHAD - Régions de Logone occidental et Logone Oriental Pour usage humanitaire uniquement Carte de référence Date de production: 07 septembre 2018 15°30'0"E 16°0'0"E 16°30'0"E 17°0'0"E Gounou Koré Marba Kakrao Ambasglao Boudourr Oroungou Gounaye Djouman Goubou Gabrigué Tagal I Drai Mala Djoumane Disou Kom Tombouo Landou Marba Gogor Birem Dikna Goundo Nongom Goumga Zaba I Sadiki Ninga Pari N N " Baktchoro Narégé " 0 0 ' Pian Bordo ' 0 0 3 Bérem Domo Doumba 3 ° ° 9 Brem 9 Tchiré Gogor Toguior Horey Almi Zabba Djéra Kolobaye Kouma Tchindaï Poum Mbassa Kahouina Mogoy Gadigui Lassé Fégué Kidjagué Kabbia Gounougalé Bagaye Bourmaye Dougssigui Gounou Ndolo Aguia Tchilang Kouroumla Kombou Nergué Kolon Laï Batouba Monogoy Darbé Bélé Zamré Dongor Djouni Koubno Bémaye Koli Banga Ngété Tandjile Goun Nanguéré Tandjilé Dimedou Gélgou Bongor Madbo Ouest Nangom Dar Gandil Dogou Dogo Damdou Ngolo Tchapadjigué Semaïndi Layane Béré Delim Kélo Dombala Tchoua Doromo Pont-Carol Dar Manga Beyssoa Manaï I Baguidja Bormane Koussaki Berdé Tandjilé Est Guidari Tandjilé Guessa Birboti Tchagra Moussoum Gabri Ngolo Kabladé Kasélem Centre Koukwala Toki Béro Manga Barmin Marbelem Koumabodan Ter Kokro Mouroum Dono-Manga Dono Manga Nantissa Touloum Kalité Bayam Kaga Palpaye Mandoul Dalé Langué Delbian Oriental Tchagra Belimdi Kariadeboum Dilati Lao Nongara Manga Dongo Bitikim Kangnéra Tchaouen Bédélé Kakerti Kordo Nangasou Bir Madang Kemkono Moni Bébala I Malaré Bologo Bélé Koro Garmaoa Alala Bissigri Dotomadi Karangoye Dadjilé Saar-Gogne Bala Kaye Mossoum Ngambo Mossoum -

Myr 2010 Chad.Pdf

ORGANIZATIONS PARTICIPATING IN CONSOLIDATED APPEAL CHAD ACF CSSI IRD UNDP ACTED EIRENE Islamic Relief Worldwide UNDSS ADRA FAO JRS UNESCO Africare Feed the Children The Johanniter UNFPA AIRSERV FEWSNET LWF/ACT UNHCR APLFT FTP Mercy Corps UNICEF Architectes de l’Urgence GOAL NRC URD ASF GTZ/PRODABO OCHA WFP AVSI Handicap International OHCHR WHO BASE HELP OXFAM World Concern Development Organization CARE HIAS OXFAM Intermon World Concern International CARITAS/SECADEV IMC Première Urgence World Vision International CCO IMMAP Save the Children Observers: CONCERN Worldwide INTERNEWS Sauver les Enfants de la Rue International Committee of COOPI INTERSOS the Red Cross (ICRC) Solidarités CORD IOM Médecins Sans Frontières UNAIDS CRS IRC (MSF) – CH, F, NL, Lux TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................. 1 Table I: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by cluster) ................................................... 3 Table II: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by appealing organization).......................... 4 Table III: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by priority)................................................... 5 2. CHANGES IN THE CONTEXT, HUMANITARIAN NEEDS AND RESPONSE ........................................... 6 3. PROGRESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES AND SECTORAL TARGETS .......... 9 3.1 STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................ -

Chad: a New Conflict Resolution Framework

CHAD: A NEW CONFLICT RESOLUTION FRAMEWORK Africa Report N°144 – 24 September 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................I I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. A CRISIS OF THE STATE ........................................................................................... 2 A. 1990-2000: MISSED OPPORTUNITIES FOR RECONCILIATION......................................................2 B. OIL, CLIENTELISM AND CORRUPTION........................................................................................3 1. Clientelism and generalised corruption ..............................................................................3 2. The oil curse .......................................................................................................................4 C. MILITARISATION OF THE ADMINISTRATION AND POPULATION ..................................................5 D. NATIONAL AND RELIGIOUS DIVIDES .........................................................................................6 III. THE ACTORS IN THE CRISIS................................................................................... 8 A. THE POLITICAL OPPOSITION .....................................................................................................8 1. Repression and co-option ...................................................................................................8 2. The political platform of -

Chad: the Victims of Hissène Habré Still Awaiting Justice

Human Rights Watch July 2005 Vol. 17, No. 10(A) Chad: The Victims of Hissène Habré Still Awaiting Justice Summary......................................................................................................................................... 1 Principal Recommendations to the Chadian Government..................................................... 2 Historical Background.................................................................................................................. 3 The War against Libya and Internal Conflicts in Chad....................................................... 3 The Regime of Hissène Habré................................................................................................ 4 The Documentation and Security Directorate (DDS) ........................................................ 5 The Crimes of Hissène Habré’s Regime ............................................................................... 8 The Fall of Hissène Habré and the Truth Commission’s Report ................................... 14 The Chadian Association of Victims of Political Repression and Crime....................... 16 Victim Rehabilitation.............................................................................................................. 17 The Prosecution of Hissène Habré...................................................................................... 18 The Victims of Hissène Habré Still Awaiting Justice in Chad .............................................22 Hissène Habré’s Accomplices Still in Positions