District 9 (2009), the Process Is Perceived As a Grotesque Calamity, While in James Cameron’S Avatar (2009), It Is Experienced As a Redemptive Empowerment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALL Code Sheets

Name: _________________________ Code Name: _________________________ Alien Nation® Cursive Alphabet In the science fiction movie “Alien Nation” the Tenctonese people have an alphabet that corresponds to our alphabet. They even have print and cursive versions of their language. The cursive letters should be connected when spelling a word. Use the alphabet to spell 10 of your spelling words. The word “SPELLING” is done for you as an example. LIST WORD WRITTEN IN CODE EX. S P E L L I N G 1. ___________________ __________________________________________ 2. ___________________ __________________________________________ 3. ___________________ __________________________________________ 4. ___________________ __________________________________________ 5. ___________________ __________________________________________ 6. ___________________ __________________________________________ 7. ___________________ __________________________________________ 8. ___________________ __________________________________________ 9. ___________________ __________________________________________ 10. __________________ __________________________________________ Created by K. S. Spencer Name: _________________________ Code Name: _________________________ Alien Nation® Print Alphabet In the science fiction movie “Alien Nation” the Tenctonese people have an alphabet that corresponds to our alphabet. They even have print and cursive versions of their language. Use the alphabet to spell 10 of your spelling words. The word “SPELLING” is done for you as an example. LIST WORD -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents PART I. Introduction 5 A. Overview 5 B. Historical Background 6 PART II. The Study 16 A. Background 16 B. Independence 18 C. The Scope of the Monitoring 19 D. Methodology 23 1. Rationale and Definitions of Violence 23 2. The Monitoring Process 25 3. The Weekly Meetings 26 4. Criteria 27 E. Operating Premises and Stipulations 32 PART III. Findings in Broadcast Network Television 39 A. Prime Time Series 40 1. Programs with Frequent Issues 41 2. Programs with Occasional Issues 49 3. Interesting Violence Issues in Prime Time Series 54 4. Programs that Deal with Violence Well 58 B. Made for Television Movies and Mini-Series 61 1. Leading Examples of MOWs and Mini-Series that Raised Concerns 62 2. Other Titles Raising Concerns about Violence 67 3. Issues Raised by Made-for-Television Movies and Mini-Series 68 C. Theatrical Motion Pictures on Broadcast Network Television 71 1. Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 74 2. Additional Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 80 3. Issues Arising out of Theatrical Films on Television 81 D. On-Air Promotions, Previews, Recaps, Teasers and Advertisements 84 E. Children’s Television on the Broadcast Networks 94 PART IV. Findings in Other Television Media 102 A. Local Independent Television Programming and Syndication 104 B. Public Television 111 C. Cable Television 114 1. Home Box Office (HBO) 116 2. Showtime 119 3. The Disney Channel 123 4. Nickelodeon 124 5. Music Television (MTV) 125 6. TBS (The Atlanta Superstation) 126 7. The USA Network 129 8. Turner Network Television (TNT) 130 D. -

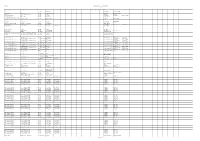

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

Elysium & Avatar

DOI: 10.32001/sinecine.741686 • Araştırma Makalesi | Research Article BETWEEN GREEN PARADISE AND BLEAK CALAMITY: ELYSIUM & AVATAR Cenk Tan Abstract Literary utopias and dystopias reflect a wide variety of concerns, from class and gender issues to the environment. These works not only reflect current social matters but also provide a glimpse of possible futures and a warning of perils to come. This article analyzes two science fiction films that have been in the spotlight during the last decade: Elysium (Neill Blomkamp, 2013) and Avatar (James Cameron, 2009). The two films depict disparate, dystopian visions of humanity’s future, yet both center on the themes of colonialism and the exploitation of the natural environment and offer ambiguous, open-ended conclusions. Focusing on these themes, this study applies postcolonial ecocriticism to expose the relationship between colonialism and ecocriticism and to show that the subtexts of both films deliver messages about the irrevocable destruction of the natural environment as an unconditional result of colonialism, impressing upon viewers the urgent need to adopt and implement an ecocentric mentality that will lead humanity to a peaceful and sustainable future. Keywords: Elysium, Avatar, Utopian/Dystopian fiction, film studies, postcolonial ecocriticism. Geliş Tarihi | Received: 23.05.2020 • Kabul Tarihi | Accepted: 14.09.2020 30 Eylül 2020 Tarihinde Online Olarak Yayınlanmıştır. Öğr. Gör. Dr., Pamukkale Üniversitesi Yabancı Diller Yüksekokulu ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2451-3612 • E-Posta: [email protected] Tan, C. (2020). Between Green Paradise and Bleak Calamity: Elysium & Avatar. sinecine, 11(2), 301-323. YEŞIL CENNETLE KASVETLI FELAKET ARASINDA: ELYSIUM & AVATAR Öz Ütopya/distopya yazını sınıf mücadelesinden, cinsiyet ve çevre sorunlarına kadar sosyal konuları ele almaktadır. -

Ground Into Sky: the Topology of Interstellar

The Avery Review Fred scharmen – Ground into Sky: The Topology of Interstellar Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar was nominated for five Oscars. The Citation: Fred Scharmen, “Ground Into Sky: The Topology of Interstellar,” in The Avery Review, no. 6 movie won the Oscar for Best Visual Effects, many of which were created with (March 2015), http://averyreview.com/issues/6/ analog camera techniques. It has been controversial for its use of emotional ground-into-sky. themes, and its scientific accuracy. The physics in the film is either shockingly sloppy, or accurate enough to generate new peer-reviewed research, depend- ing on which review you read. [1] [2] But the best and most curious thing about [1] Phil Plait, “Interstellar Science: What the movie gets wrong and really wrong about black Interstellar is its topology. holes, relativity, plot, and dialogue,” Slate, http:// Again and again, in different ways, we see the ground lifting up to www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/ space_20/2014/11/interstellar_science_review_ become the sky. The first appearance of this effect is early in the movie—the the_movie_s_black_holes_wormholes_relativity.html, horizon-obliterating dust storms that sweep across the American Midwest. accessed February 24, 2015. Cooper (the main character) and his family are at a baseball game when a dust [2]: Adam Rogers, “Wrinkles in Spacetime: The Warped Astrophysics of Interstellar,” Wired, http:// storm rises, looming like a growing mountain. Drought and blight have killed the www.wired.com/2014/10/astrophysics-interstellar- plant life that binds the soil, the near-future world of the movie has become a black-hole/, accessed February 24, 2015. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

April 2010 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle April 2010 The Next NASFA Meeting is 17 April 2010 at the Regular Time and Location Con†Stellation XXIX ConCom Meeting 3P, 17 April 2010 at Renasant Bank (right before the club meeting) COOKOUT/PICNIC IN MAY d Oyez, Oyez d The More-or-Less-Annual NASFA Cookout/Picnic will be in May at Peggy Patrick’s house on the regular club meeting day. It’s The next NASFA Meeting is Saturday 17 April 2010 at the expected to start at about 2P, though stay tuned. This will affect regular time (6P) and the regular location. Meetings are at the concom meeting, normally scheduled for 3P that same day. the Renasant Bank’s Community Room, 4245 Balmoral Drive SHUTTLE TRANSITION—REDUX in south Huntsville. Exit the Parkway at Airport Road; head Once again production of the Shuttle is undergoing a transi- east one short block to Balmoral Drive; turn left (north) for less tion—this time forced by the death of one computer and the than a block. The bank is on the right, just past Logan’s Road- acquisition of its replacement. Things may be uneven for a house restaurant. Enter at the front door of the bank; turn right while; please bear with us. to the end of a short hallway. NASFA CALENDAR ONLINE MARCH PROGRAM NASFA has an online calendar on Google. Interested parties The April program will be “Darrell Osborn Talks about Crea- can check the calendar online, but you can also subscribe to the tivity.” calendar and have your Outlook, iCal, BlackBerry, or other ATMMs calendar automatically updated as events (Club Meetings, Con- The April After-The-Meeting Meeting will be at Sue Thorn’s com Meetings, local sf/f events) are added or changed. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin J

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement Justin J. Grandinetti James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Rhetoric Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grandinetti, Justin J., "Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement" (2015). Masters Theses. 43. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/43 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Occupy the Future: A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin Grandinetti A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communication May 2015 Dedication Page This thesis is dedicated to the world’s revolutionaries and all the individuals working to make the planet a better place for future generations. ii Acknowledgements I’d like to thank a number of people for their assistance and support with this thesis project. First, a heartfelt thank you to my thesis chair, Dr. Jim Zimmerman, for always being there to make suggestions about my drafts, talk about ideas, and keep me on schedule. -

Slayage, Number 20: Blasingame

Katrina Blasingame “I Can’t Believe I’m Saying It Twice in the Same Century. but ‘Duh . .’”1 The Evolution of Buffy the Vampire Slayer Sub-Culture Language through the Medium of Fanfiction [1] I became interested in the evolution of fan language due to the story from which the title of this article derives, Chocolaty Goodness by Mad Poetess. Mad Poetess appropriates canonical language constructions from the Buffy mythos, changes them into something completely her own yet still recognizably from Buffy. Reading Mad Poetess led me to speculate that fanfiction writers are internalizing Buffy’s language and style for their own ends, their fanfiction, and especially for characterization within their fanfictional worlds. As a fanfiction writer, I find myself applying the playfulness I witnessed in Buffy, and later Angel and Firefly, to non-Whedon texts like Stargate: Atlantis.2 I also find other writers, whether familiar with Whedon-texts or not, who use language with a Whedonesque flair. Fanfiction is copious on the Internet, so I have chosen to illustrate the Buffy influence on fanfiction language from a small and admittedly personal selection. Though not a comprehensive reading of fanfiction language, this article is an introduction, a place to start that can be applied to all Buffy fanfiction and, potentially, further afield and applied to other fanfiction appropriated universes, perhaps even further, in the course of history, to mainstream English. [2] The idea of an evolving fan language is a bit confounding. Admittedly, language constructions in fanfiction are difficult to track from fanfiction’s modern origins in series like Star Trek, Star Wars, and Blake’s 7, to current fan creations related to series like Stargate: SG-1, Andromeda, X-Files, or Buffy the Vampire Slayer. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Alien Nation M2

ALIEN NATION "Body and Soul" Diane Frolov & Andrew Schneider Draft No. - Unknown Draft Date - Unknown - '90 ACT ONE FADE IN: EXT. LITTLE TENCTON - NIGHT Deserted. Murky broken by the intermittent pools of light from the street lamps. POUNDING FOOTSTEPS -- SHOUTS! A huge shadow of a running man looms against the wall of a tenement. A NEWCOMER GIANT fully seven feet tall, cradles a Newcomer infant GIRL as he runs. His eyes, full of fear, are the eyes of the hunted. HIS PURSUER are two men -- one a human, JONES; the other a Newcomer, PENN. TWO NEWCOMER TRANSIENTS male and female, stagger from CLANCY'S MILK BAR. They look up startled as the giant lurches toward them. GIANT {Help me...! Help me...!} The male backs away. The woman stares with demented glee, CACKLING. The giant runs from building to building, POUNDING on the doors. GIANT {Help me...!} Windows fly open -- Newcomers appear at them, calling out: HEY, GET AWAY FROM THERE! KEEP IT QUIET! I'M CALLING THE POLICE! The giant lumbers on, coming to: AN OVERPASS spanning a four-lane road. The giant pounds onto the overpass. Reaching the middle, he stops, staring fearfully at: ANOTHER NEWCOMER - HUDSON RIVER Who blocks his path. River holds a syringe. RIVER {No one's going to hurt you...} Terrified, the giant, starts backing away, but he's trapped by the other pursuers approaching from behind. RIVER Come with us... we won't hurt you. In the distance, a SIREN wails. River and his men close in. The giant sets the infant down. Grabbing the newcomer Penn, he hurls him at River. -

Elite Rhetoric, Target Group Positioning, and Policymaking: Immigrant Women and Project 100% in San Diego County

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CGU Theses & Dissertations CGU Student Scholarship Spring 2021 Elite Rhetoric, Target Group Positioning, and Policymaking: Immigrant Women and Project 100% in San Diego County Amy Nantkes Claremont Graduate University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd Recommended Citation Nantkes, Amy. (2021). Elite Rhetoric, Target Group Positioning, and Policymaking: Immigrant Women and Project 100% in San Diego County. CGU Theses & Dissertations, 219. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/ cgu_etd/219. doi: 10.5642/cguetd/219 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the CGU Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in CGU Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elite Rhetoric, Target Group Positioning, and Policymaking: Immigrant Women and Project 100% in San Diego County By Amy Nantkes Claremont Graduate University 2021 © Copyright Amy Nantkes, 2021. All rights reserved Approval of the Dissertation Committee This dissertation has been duly read, reviewed, and critiqued by the Committee listed below, which hereby approves the manuscript of Amy Nantkes as fulfilling the scope and quality requirements for meriting the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science. Dr. Melissa Rogers, Chair Associate Professor of International Studies Claremont Graduate University Dr. Jean Schroedel Professor Emerita of Political Science Claremont Graduate University Dr. Heather Campbell Professor, Department of Politics and Government Claremont Graduate University Abstract Elite Rhetoric, Target Group Positioning, and Policymaking: Immigrant Women and Project 100% in San Diego County By Amy Nantkes Claremont Graduate University: 2021 Thousands of Mexicans are crossing the U.S.