Alien Rumination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Small Island

We're a Small Island: The Greening of Intolerance by Sarah Sexton, Nicholas Hildyard and Larry Lohmann, The Corner House, UK presentation at Friends of the Earth (England and Wales), 7th April 2005 Introduction (by Sarah Sexton) For those of you who remember your school days, or if you have 16-year-olds among your family and friends, you'll know that April/May is nearly GCSE exam time, 1 a time of revision, panic and ... set books. One on this year's syllabus is A Tale of Two Cities . (If you were expecting me to say Bill Bryson's Notes From A Small Island , or even better, Andrea Levy's Small Island , they're for next year. 2) Charles Dickens's story about London and Paris is set at the time of the French Revolution, 1789 onwards, a time when the English hero—I won't tell you what happens at the end just in case you haven't seen the film—didn't need an official British passport to travel to another country, although British sovereigns had long issued documents requesting "safe passage or pass" to anyone in Britain who wanted to travel abroad. It was in 1858, some 70 years later, that the UK passport became available only to United Kingdom nationals, and thus in effect became a national identity document as well as an aid to travel. 3 A Tale of Two Cities was published one year later in 1859. These days, students are encouraged to do more field work than when I was at school. -

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

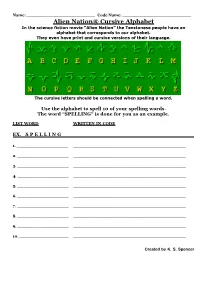

ALL Code Sheets

Name: _________________________ Code Name: _________________________ Alien Nation® Cursive Alphabet In the science fiction movie “Alien Nation” the Tenctonese people have an alphabet that corresponds to our alphabet. They even have print and cursive versions of their language. The cursive letters should be connected when spelling a word. Use the alphabet to spell 10 of your spelling words. The word “SPELLING” is done for you as an example. LIST WORD WRITTEN IN CODE EX. S P E L L I N G 1. ___________________ __________________________________________ 2. ___________________ __________________________________________ 3. ___________________ __________________________________________ 4. ___________________ __________________________________________ 5. ___________________ __________________________________________ 6. ___________________ __________________________________________ 7. ___________________ __________________________________________ 8. ___________________ __________________________________________ 9. ___________________ __________________________________________ 10. __________________ __________________________________________ Created by K. S. Spencer Name: _________________________ Code Name: _________________________ Alien Nation® Print Alphabet In the science fiction movie “Alien Nation” the Tenctonese people have an alphabet that corresponds to our alphabet. They even have print and cursive versions of their language. Use the alphabet to spell 10 of your spelling words. The word “SPELLING” is done for you as an example. LIST WORD -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents PART I. Introduction 5 A. Overview 5 B. Historical Background 6 PART II. The Study 16 A. Background 16 B. Independence 18 C. The Scope of the Monitoring 19 D. Methodology 23 1. Rationale and Definitions of Violence 23 2. The Monitoring Process 25 3. The Weekly Meetings 26 4. Criteria 27 E. Operating Premises and Stipulations 32 PART III. Findings in Broadcast Network Television 39 A. Prime Time Series 40 1. Programs with Frequent Issues 41 2. Programs with Occasional Issues 49 3. Interesting Violence Issues in Prime Time Series 54 4. Programs that Deal with Violence Well 58 B. Made for Television Movies and Mini-Series 61 1. Leading Examples of MOWs and Mini-Series that Raised Concerns 62 2. Other Titles Raising Concerns about Violence 67 3. Issues Raised by Made-for-Television Movies and Mini-Series 68 C. Theatrical Motion Pictures on Broadcast Network Television 71 1. Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 74 2. Additional Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 80 3. Issues Arising out of Theatrical Films on Television 81 D. On-Air Promotions, Previews, Recaps, Teasers and Advertisements 84 E. Children’s Television on the Broadcast Networks 94 PART IV. Findings in Other Television Media 102 A. Local Independent Television Programming and Syndication 104 B. Public Television 111 C. Cable Television 114 1. Home Box Office (HBO) 116 2. Showtime 119 3. The Disney Channel 123 4. Nickelodeon 124 5. Music Television (MTV) 125 6. TBS (The Atlanta Superstation) 126 7. The USA Network 129 8. Turner Network Television (TNT) 130 D. -

Ethnic Lobbying and Diaspora Politics in the US the Case of the Pro

Title: Ethnic Lobbying and Diaspora Politics in the U.S. The Case of the Pro-Palestinian Movement Author: Michelle M. Dekker, 3001245 Billitonkade 74, 3531 TK, Utrecht The Netherlands Email: [email protected] Course Information: Universiteit Utrecht MA Internationale Betrekkingen in historisch perspectief (International Relations in an historical perspective) 200400645 Ges-Thesis Hand-in date : May 25, 2010 Ethnic Lobbying and Diaspora Politics in the U.S. The Case of the Pro-Palestinian Movement M.M. Dekker - 3001245 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter One .................................................................................................................................................... 10 Ethnic Lobbying in the US ..................................................................................................................... 12 Influential Ethnic Lobbies in the US .................................................................................................. 15 Ethnic Lobbying Strategies ................................................................................................................... 20 Electoral Power .................................................................................................................................... 20 Financial Resources ........................................................................................................................... -

871 References Noted Herein + 354 Christian Scripture & Early Churchmen Quotes, + 59 Hebrew Chapter 1

A 1,284 source quotes (871 references noted herein + 354 Christian scripture & early churchmen quotes, + 59 Hebrew bible/ deuterocanonical references “Ibid.” = in its place in noted section) Chapter 1 1: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religulous 2: English poet John Milton in Areopagitica 1644 3: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Emperor’s_New_Clothes 4: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Orwell Chapter 2 1: See chapter 1’s reference 2: Relativism: Lecture on CD by Chris Stefanick; ©2013 Lighthouse Catholic Media, NFP 3: https://www.conservapedia.com/Dunning-Kruger_effect OR Why Incompetent People Think They’re Amazing (video): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pOLmD_WVY-E 4~ https://listverse.com/2013/06/16/10-reasons-why-democracy-doesnt-work/ 5: Video: Non-college Educated Does Not Mean Dumb https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cnDej56K56A&t=3 OR www.freedomain.blogspot.com/2017/03/dont-go-to-college.html 6~Ibid. 7~www.churchofsatan.com 8~ https://www.amazon.com/American-Grace-Religion-Divides-Unites/dp/1416566732 9~ 2011 New York Times Almanac (Penguin Reference) p. 605 10: www.answering-islam.org/Authors/Arlandson/contrast.htm Chapter 3 1: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_energy 2: ‘Decoding the Most Complex Structure in the Universe’: NPR www.npr.org 3: https://www.wired.com/2008/01/mapping-the-most-complex-structure-in-the-universe-your-brain/ 4~ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occam’s_razor 5: https://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/newtlaws/Lesson-1/Newton-s-First-Law 6: https://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/newtlaws/Lesson-4/Newton-s-Third-Law 7: From Webster’s Third New International Dictionary Unabridged; p. -

From Ethnomathematics to Ethnocomputing

1 Bill Babbitt, Dan Lyles, and Ron Eglash. “From Ethnomathematics to Ethnocomputing: indigenous algorithms in traditional context and contemporary simulation.” 205-220 in Alternative forms of knowing in mathematics: Celebrations of Diversity of Mathematical Practices, ed Swapna Mukhopadhyay and Wolff- Michael Roth, Rotterdam: Sense Publishers 2012. From Ethnomathematics to Ethnocomputing: indigenous algorithms in traditional context and contemporary simulation 1. Introduction Ethnomathematics faces two challenges: first, it must investigate the mathematical ideas in cultural practices that are often assumed to be unrelated to math. Second, even if we are successful in finding this previously unrecognized mathematics, applying this to children’s education may be difficult. In this essay, we will describe the use of computational media to help address both of these challenges. We refer to this approach as “ethnocomputing.” As noted by Rosa and Orey (2010), modeling is an essential tool for ethnomathematics. But when we create a model for a cultural artifact or practice, it is hard to know if we are capturing the right aspects; whether the model is accurately reflecting the mathematical ideas or practices of the artisan who made it, or imposing mathematical content external to the indigenous cognitive repertoire. If I find a village in which there is a chain hanging from posts, I can model that chain as a catenary curve. But I cannot attribute the knowledge of the catenary equation to the people who live in the village, just on the basis of that chain. Computational models are useful not only because they can simulate patterns, but also because they can provide insight into this crucial question of epistemological status. -

Slayage, Number 20: Blasingame

Katrina Blasingame “I Can’t Believe I’m Saying It Twice in the Same Century. but ‘Duh . .’”1 The Evolution of Buffy the Vampire Slayer Sub-Culture Language through the Medium of Fanfiction [1] I became interested in the evolution of fan language due to the story from which the title of this article derives, Chocolaty Goodness by Mad Poetess. Mad Poetess appropriates canonical language constructions from the Buffy mythos, changes them into something completely her own yet still recognizably from Buffy. Reading Mad Poetess led me to speculate that fanfiction writers are internalizing Buffy’s language and style for their own ends, their fanfiction, and especially for characterization within their fanfictional worlds. As a fanfiction writer, I find myself applying the playfulness I witnessed in Buffy, and later Angel and Firefly, to non-Whedon texts like Stargate: Atlantis.2 I also find other writers, whether familiar with Whedon-texts or not, who use language with a Whedonesque flair. Fanfiction is copious on the Internet, so I have chosen to illustrate the Buffy influence on fanfiction language from a small and admittedly personal selection. Though not a comprehensive reading of fanfiction language, this article is an introduction, a place to start that can be applied to all Buffy fanfiction and, potentially, further afield and applied to other fanfiction appropriated universes, perhaps even further, in the course of history, to mainstream English. [2] The idea of an evolving fan language is a bit confounding. Admittedly, language constructions in fanfiction are difficult to track from fanfiction’s modern origins in series like Star Trek, Star Wars, and Blake’s 7, to current fan creations related to series like Stargate: SG-1, Andromeda, X-Files, or Buffy the Vampire Slayer. -

The Health Goths Are Really Feeling Zip Ties RN for Some Reason

The Health Goths Are Really Feeling Zip Ties RN For Some Reason Memes: Joelle Bouchard, @namaste.at.home.dad Text: James Payne Fashion has an eye for what is up-to-date, wherever it moves in the thickets of long ago; it's a tiger's leap into the past. Only it takes place in an arena in which the ruling classes are in control. - Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History, XIV I thought Dylann Roof was in Iceage. - James Payne Health Goth is a youth culture aesthetic formulated by the Portland trio of Chris Cantino, Mike Grabarek, and Jeremy Scott. Cantino is a video artist, while Grabarek and Scott make music as Magic Fades. In 2013, the three started a Facebook page dedicated to building the syncretic vision of Health Goth, which, as they say in an interview on Vice's i-D, centers on "sportswear, fetishization of clothing and cleanliness, body enhancement technology, rendered environments, and dystopian advertisements." A February 17th, 2017 post on the same Health Goth Facebook page is composed of three photos of black clad police officers holding zip ties used to hand-cuff protestors. In one of the three pictures, a protestor is being held to the pavement awaiting arrest. The cops surrounding him are wearing Under Armour gloves with prominently displayed logos. Coincidentally, the FB avatar for Health Goth's page is the Under Armour logo, but with smoke coming out of it, so one can tell it's countercultural, not corporate. It would be bad, after all, for Health Goth to be confused with Under Armour, whose CEO Kevin Plank has praised President Trump by saying, "To have such a pro-business president is something that is a real asset for the country. -

Alien Nation M2

ALIEN NATION "Body and Soul" Diane Frolov & Andrew Schneider Draft No. - Unknown Draft Date - Unknown - '90 ACT ONE FADE IN: EXT. LITTLE TENCTON - NIGHT Deserted. Murky broken by the intermittent pools of light from the street lamps. POUNDING FOOTSTEPS -- SHOUTS! A huge shadow of a running man looms against the wall of a tenement. A NEWCOMER GIANT fully seven feet tall, cradles a Newcomer infant GIRL as he runs. His eyes, full of fear, are the eyes of the hunted. HIS PURSUER are two men -- one a human, JONES; the other a Newcomer, PENN. TWO NEWCOMER TRANSIENTS male and female, stagger from CLANCY'S MILK BAR. They look up startled as the giant lurches toward them. GIANT {Help me...! Help me...!} The male backs away. The woman stares with demented glee, CACKLING. The giant runs from building to building, POUNDING on the doors. GIANT {Help me...!} Windows fly open -- Newcomers appear at them, calling out: HEY, GET AWAY FROM THERE! KEEP IT QUIET! I'M CALLING THE POLICE! The giant lumbers on, coming to: AN OVERPASS spanning a four-lane road. The giant pounds onto the overpass. Reaching the middle, he stops, staring fearfully at: ANOTHER NEWCOMER - HUDSON RIVER Who blocks his path. River holds a syringe. RIVER {No one's going to hurt you...} Terrified, the giant, starts backing away, but he's trapped by the other pursuers approaching from behind. RIVER Come with us... we won't hurt you. In the distance, a SIREN wails. River and his men close in. The giant sets the infant down. Grabbing the newcomer Penn, he hurls him at River. -

Elite Rhetoric, Target Group Positioning, and Policymaking: Immigrant Women and Project 100% in San Diego County

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CGU Theses & Dissertations CGU Student Scholarship Spring 2021 Elite Rhetoric, Target Group Positioning, and Policymaking: Immigrant Women and Project 100% in San Diego County Amy Nantkes Claremont Graduate University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd Recommended Citation Nantkes, Amy. (2021). Elite Rhetoric, Target Group Positioning, and Policymaking: Immigrant Women and Project 100% in San Diego County. CGU Theses & Dissertations, 219. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/ cgu_etd/219. doi: 10.5642/cguetd/219 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the CGU Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in CGU Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elite Rhetoric, Target Group Positioning, and Policymaking: Immigrant Women and Project 100% in San Diego County By Amy Nantkes Claremont Graduate University 2021 © Copyright Amy Nantkes, 2021. All rights reserved Approval of the Dissertation Committee This dissertation has been duly read, reviewed, and critiqued by the Committee listed below, which hereby approves the manuscript of Amy Nantkes as fulfilling the scope and quality requirements for meriting the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science. Dr. Melissa Rogers, Chair Associate Professor of International Studies Claremont Graduate University Dr. Jean Schroedel Professor Emerita of Political Science Claremont Graduate University Dr. Heather Campbell Professor, Department of Politics and Government Claremont Graduate University Abstract Elite Rhetoric, Target Group Positioning, and Policymaking: Immigrant Women and Project 100% in San Diego County By Amy Nantkes Claremont Graduate University: 2021 Thousands of Mexicans are crossing the U.S. -

229 INDEX © in This Web Service Cambridge

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05246-8 - The Cambridge Companion to: American Science Fiction Edited by Eric Carl Link and Gerry Canavan Index More information INDEX Aarseth, Espen, 139 agency panic, 49 Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (fi lm, Agents of SHIELD (television, 2013–), 55 1948), 113 Alas, Babylon (Frank, 1959), 184 Abbott, Carl, 173 Aldiss, Brian, 32 Abrams, J.J., 48 , 119 Alexie, Sherman, 55 Abyss, The (fi lm, Cameron 1989), 113 Alias (television, 2001–06, 48 Acker, Kathy, 103 Alien (fi lm, Scott 1979), 116 , 175 , 198 Ackerman, Forrest J., 21 alien encounters Adam Strange (comic book), 131 abduction by aliens, 36 Adams, Neal, 132 , 133 Afrofuturism and, 60 Adventures of Superman, The (radio alien abduction narratives, 184 broadcast, 1946), 130 alien invasion narratives, 45–50 , 115 , 184 African American science fi ction. assimilation of human bodies, 115 , 184 See also Afrofuturism ; race assimilation/estrangement dialectic African American utopianism, 59 , 88–90 and, 176 black agency in Hollywood SF, 116 global consciousness and, 1 black genius fi gure in, 59 , 60 , 62 , 64 , indigenous futurism and, 177 65 , 67 internal “Aliens R US” motif, 119 blackness as allegorical SF subtext, 120 natural disasters and, 47 blaxploitation fi lms, 117 post-9/11 reformulation of, 45 1970s revolutionary themes, 118 reverse colonization narratives, 45 , 174 nineteenth century SF and, 60 in space operas, 23 sexuality and, 60 Superman as alien, 128 , 129 Afrofuturism. See also African American sympathetic treatment of aliens, 38 , 39 , science fi ction ; race 50 , 60 overview, 58 War of the Worlds and, 1 , 3 , 143 , 172 , 174 African American utopianism, 59 , 88–90 wars with alien races, 3 , 7 , 23 , 39 , 40 Afrodiasporic magic in, 65 Alien Nation (fi lm, Baker 1988), 119 black racial superiority in, 61 Alien Nation (television, 1989–1990), 120 future race war theme, 62 , 64 , 89 , 95n17 Alien Trespass (fi lm, 2009), 46 near-future focus in, 61 Alien vs.