Ground Into Sky: the Topology of Interstellar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galaktika Group: Orbital City «EFIR» «Ethereal Dwelling» Space Colony Concept by Tsiolkovsky

Galaktika group: Orbital city «EFIR» «ethereal dwelling» space colony concept by tsiolkovsky BASIC PRINCIPLES OF CONSTRUCTING A SPACE COLONY UPON THE CONCEPT BY K.E. TSIOLKOVSKY: IN-SPACE ASSEMBLING MANKIND WILL NOT FOREVER REMAIN ON EARTH, BUT IN THE PURSUIT OF LIGHT AND SPACE WILL FIRST USING MATERIALS FROM PLANETS AND ASTEROIDS TIMIDLY EMERGE FROM THE BOUNDS OF THE ATMOSPHERE, AND THEN ADVANCE UNTIL HE HAS CONQUERED THE WHOLE ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY OF CIRCUMSOLAR SPACE. PLANTS CULTIVATION HE PRESENTED HIS RESEARCHES IN THE BOOKS: BEYOND THE PLANET EARTH, BIOLOGICAL LIFE IN COSMOS, ETHEREAL ISLAND, ETC. COLONY CONCEPTS [SHORT] REVIEW BERNAL'S SPHERE, STANFORD TORUS, O’NEILL’S CYLINDER BERNAL’S SPHERE STANFORD TORUS O’NEILL’S CYLINDER JOHN DESMOND BERNAL 1929 POPULATION: STUDENTS OF THE STANFORD UNIVERSITY 1975 GERARD K. O'NEILL, 1979 POPULATION: 20 MLN. 20—30 THOUSAND INHABITANTS DIAMETER POPULATION: 10 THND. AND MORE INHABITANTS INHABITANTS DIAMETER OF CYLINDERS: 6.4 KM ABOUT 16 KM DIAMETER1.8KM AND MORE LENGTH OF CYLINDERS: 32 KM ORBITAL CITY «EFIR» scheme and characteristics TOP VIEW residential torus ASSEMBLY DOCK radiators electric power station elevator 10,000 INHABITANTS DIAMETER OF TORUS – 2 KILOMETRES variable gravity module MASS OF ORBITAL CITY – 25 MLN. TONS RESIDENTIAL AREA DESCRIPTION OF THE INTERIOR AREA RESIDENTIAL AREA CHARACTERISTICS DIAMETER OF TORUS - 2 KILOMETRES ROTATION PERIOD - ONE FULL-CIRCLE TURN PER 63 SECONDS RESIDENTIAL AREA WIDTH - 300 METERS RESIDENTIAL AREA HEIGHT - 150 METERS AREA OF RESIDENTIAL ZONE - 200 HA MAXIMUM POPULATION - 10-40 THOUSAND DESIGNED POPULATION DENSITY IS 50 PEOPLE/HA TO 200 PEOPLE/HA RESIDENTIAL AREA DESCRIPTION OF THE INTERIOR AREA LOGISTICS transport plans for passengers and cargoes ORBITAL CITY AT THE LAGRANGIAN POINT INTERPLANETARY 25 MLN. -

General Issue

Journal of the British Interplanetary Society VOLUME 72 NO.5 MAY 2019 General issue A REACTION DRIVE Powered by External Dynamic Pressure Jeffrey K. Greason DOCKING WITH ROTATING SPACE SYSTEMS Mark Hempsell MARTIAN DUST: the Formation, Composition, Toxicology, Astronaut Exposure Health Risks and Measures to Mitigate Exposure John Cain THE CONCEPT OF A LOW COST SPACE MISSION to Measure “Big G” Roger Longstaff www.bis-space.com ISSN 0007-084X PUBLICATION DATE: 26 JULY 2019 Submitting papers International Advisory Board to JBIS JBIS welcomes the submission of technical Rachel Armstrong, Newcastle University, UK papers for publication dealing with technical Peter Bainum, Howard University, USA reviews, research, technology and engineering in astronautics and related fields. Stephen Baxter, Science & Science Fiction Writer, UK James Benford, Microwave Sciences, California, USA Text should be: James Biggs, The University of Strathclyde, UK ■ As concise as the content allows – typically 5,000 to 6,000 words. Shorter papers (Technical Notes) Anu Bowman, Foundation for Enterprise Development, California, USA will also be considered; longer papers will only Gerald Cleaver, Baylor University, USA be considered in exceptional circumstances – for Charles Cockell, University of Edinburgh, UK example, in the case of a major subject review. Ian A. Crawford, Birkbeck College London, UK ■ Source references should be inserted in the text in square brackets – [1] – and then listed at the Adam Crowl, Icarus Interstellar, Australia end of the paper. Eric W. Davis, Institute for Advanced Studies at Austin, USA ■ Illustration references should be cited in Kathryn Denning, York University, Toronto, Canada numerical order in the text; those not cited in the Martyn Fogg, Probability Research Group, UK text risk omission. -

Thematic, Moral and Ethical Connections Between the Matrix and Inception

Thematic, Moral and Ethical Connections Between the Matrix and Inception. Modern Day science and technology has been crucial in the development of the modern film industry. In the past, directors have been confined by unwieldy, primitive cameras and the most basic of special effects. The contemporary possibilities now available has enabled modern film to become more dynamic and versatile, whilst also being able to better capture the performance of actors, and better display scenes and settings using special effects. As the prevalence of technology in society increases, film makers have used their medium to express thematic, moral and ethical concerns of technology in human life. The films I will be looking at: The Matrix, directed by the Wachowskis, and Inception, directed by Christopher Nolan, both explore strong themes of technology. The theme of technology is expanded upon as the directors of both films explore the use of augmented reality and its effects on the human condition. Through the use of camera angles, costuming and lighting, the Witkowski brothers represent the idea that technology is dangerous. During the sequence where neo is unplugged from the Matrix, the directors have cleverly combines lighting, visual and special effects to craft an ominous and unpleasant setting in which the technology is present. Upon Neo’s confrontation with the spider drone, the use of camera angles to establishes the dominance of technology. The low-angle shot of the drone places the viewer in a subordinate position, making the drone appear powerful. The dingy lighting and poor mis-en-scene in the set further reinforces the idea that technology is dangerous. -

Tailored Force Fields for Space-Based Construction: Key to a Space-Based Economy Phase 1 Final Report

Tailored Force Fields for Space-Based Construction: Key to a Space-Based Economy Phase 1 Final Report NIAC-CP-01-02, USRA Subcontract 07600-091 Narayanan Komerath Sam Wanis, Balakrishnan Ganesh, Joseph Czechowski, Waqar Zaidi, Joshua Hardy, Priya Gopalakrishnan School of Aerospace Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta GA 30332-0150 [email protected] November 2002 Contents 1. Abstract Page 3 2.Introduction to Tailored Force Fields 4 Forces in steady and unsteady potential fields Time line / Application Roadmap 3.Theory connecting acoustic, optical, microwave and radio regimes. 7 4. Task Report: Acoustic Shaping 12 Prior results Inverse-design Shape Generation Software 5. Task Report: Intermediate Term: Architecture for Radiation Shield Project Near Earth 16 Shield-Building Architecture. Launcher and boxcar considerations Deployment of the Outer Grid of the Radiation Shield “Shepherd” Rendezvous-Guidance-Delivery Vehicles. 6. Task Report: Exploration of cost and architecture models for a Space-Based 24 Economy 7. Task Report: Exploration of large-scale construction using Asteroids and Radio 34 Waves Parameter space and design point Power and material requirements Technology status 8. Opportunities& Outreach related to this project 45 SEM Expt. Preparation GAS Expt. Preparation Papers, presentations, discussions Media coverage & public interest “NASA Means Business” program synergy 9. Summary of Issues Identified 49 Metal production and hydrogen recycling Resonator / waveguide technology Cost linkage to comprehensive plan Microwave demonstrator experiment 10. Conclusions 51 11. Acknowledgements 53 12. References 54 2 1. Abstract Before humans can venture to live for extended periods in Space, the problem of building radiation shields must be solved. All current concepts for permanent radiation shields involve very large mass, and expensive and hazardous construction methods. -

An Asymptote of Reality: an Analysis of Nolan's "Inception" Carson Ratliff Grand Valley State University

Cinesthesia Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 4 12-1-2012 An Asymptote of Reality: An Analysis of Nolan's "Inception" Carson Ratliff Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ratliff, Carson (2012) "An Asymptote of Reality: An Analysis of Nolan's "Inception"," Cinesthesia: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine/vol1/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cinesthesia by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ratliff: An Asymptote of Reality An Asymptote of Reality: An Analysis of Nolan’s Inception In the first act of Inception (Christopher Nolan, 2010), dream invaders Thomas Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Ariadne (Ellen Page) are walking through the world of a dream. This being her first time in the alternate reality, Ariadne is in awe of the realism of the world. Cobb explains to her that it will be her job, as a dream architect, to design the dream world to make it accurately reflect real life. Ariadne seems intrigued by this challenge and inquires, “…What happens when you start messing with the physics of it all?” At this, the pair stop in their tracks as Ariadne starts to reshape the world of the dream, folding the horizon up into the sky until it comes to rest upside down, one hundred yards above the two protagonists’ heads. -

The Performance and Materiality of the Processes, Spaces and Labor of VFX Production

Sarah Atkinson Interactive ‘making-of’ machines: The performance and materiality of the processes, spaces and labor of VFX production Abstract This article analyzes and interrogates two interactive museum installations designed to reveal behind-the-scenes visual effects (VFX) materials from Inception (2010) and Gravity (2013). The multi-screen, interactive, and immersive installations were both created in direct collaboration with the VFX supervisors who were responsible for pioneering the new and innovative creative solutions in each of the films. The installations translate these processes for a wider audience and as such they not only provide rich sites for textual analysis as new ancillary forms of paratextual access, but they also provide insights into the way that VFX sector presents itself, situated within the wider context of the current global VFX industry. The article draws together critical production studies, textual analysis, and reflections from the industry which, combined, provide new understandings of these interactive forms of ancillary film “making-of ” content, their performative dimensions, and the labor processes that they reveal. Context their conception and presentation within the wider context of the current global VFX industry. This article analyzes and interrogates two interactive The decadent displays of VFX excess and access museum installations that were designed to reveal presented in both installations are representative of behind-the-scenes materials from Inception (2010) the currently flourishing VFX industry within the and Gravity (2013) in order to showcase the UK which has been boosted in recent years, by a acclaimed, breakthrough visual effects (VFX) of system of tax incentives which have been in place 3 each of the films. -

Allianz Global Insurance Report 2020: Skyfall

stock.adobe.com - © Davies Stephen ALLIANZ INSURANCE REPORT 2020 SKYFALL 01 July 2020 02 Looking back: License to insure 10 Coronomics: Tomorrow never dies 16 Money? Penny? Outlook for the coming decade 22 No time to die: ESG as the next business frontier in insurance Allianz Research The global insurance industry entered 2020 in good shape: In 2019, premiums increa- sed by +4.4%, the strongest growth since 2015. The increase was driven by the life seg- EXECUTIVE ment, where growth sharply increased over 2018 to +4.4% as China overcame its tem- porary, regulatory-induced setback and mature markets finally came to grips with low interest rates. P&C clocked the same rate of growth (+4.3%), down from +5.4% in 2018. SUMMARY Global premium income totaled EUR3,906bn in 2019 (life: EUR2,399bn, P&C: EUR1,507bn). Then, Covid-19 hit the world economy like a meteorite. The sudden stop of economic activity around the globe will batter insurance demand, too: Global premium income is expected to shrink by -3.8% in 2020 (life: -4.4%, P&C: -2.9%), three times the pace wit- nessed during the Global Financial Crisis. Compared to the pre-Covid-19 growth trend, the pandemic will shave around EUR358bn from the global premium pool (life: Michaela Grimm, Senior Economist EUR249bn, P&C: EUR109bn). [email protected] In line with our U-shaped scenario for the world economy, premium growth will re- bound in 2021 to +5.6% and total premium income should return to the pre-crisis level. The losses against the trend, however, may never be recouped: although long-term growth until 2030 may reach +4.4% (life: 4.4%, P&C: 4.5%), this will be slightly below previous projections. -

Inception and Ibn 'Arabi Oludamini Ogunnaike Harvard University, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 17 Article 10 Issue 2 October 2013 10-2-2013 Inception and Ibn 'Arabi Oludamini Ogunnaike Harvard University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Ogunnaike, Oludamini (2013) "Inception and Ibn 'Arabi," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol17/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Inception and Ibn 'Arabi Abstract Many philosophers, playwrights, artists, sages, and scholars throughout the ages have entertained and developed the concept of life being a "but a dream." Few works, however, have explored this topic with as much depth and subtlety as the 13thC Andalusian Muslim mystic, Ibn 'Arabi. Similarly, few works of art explore this theme as thoroughly and engagingly as Chistopher Nolan's 2010 film Inception. This paper presents the writings of Ibn 'Arabi and Nolan's film as a pair of mirrors, in which one can contemplate the other. As such, the present work is equally a commentary on the film based on Ibn 'Arabi's philosophy, and a commentary on Ibn 'Arabi's work based on the film. The ap per explores several points of philosophical significance shared by the film and the work of the Sufi as ge, and their relevance to contemporary conversations in philosophy, religion, and art. Keywords Ibn 'Arabi, Sufism, ma'rifah, world as a dream, metaphysics, Inception, dream within a dream, mysticism, Christopher Nolan Author Notes Oludamini Ogunnaike is a PhD candidate at Harvard University in the Dept. -

California State University, Northridge Low Earth Orbit

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE LOW EARTH ORBIT BUSINESS CENTER A Project submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering by Dallas Gene Bienhoff May 1985 The Proj'ectof Dallas Gene Bienhoff is approved: Dr. B. J. Bluth Professor T1mothy Wm. Fox - Chair California State University, Northridge ii iii ACKNOWLEDGEHENTS I wish to express my gratitude to those who have helped me over the years to complete this thesis by providing encouragement, prodding and understanding: my advisor, Tim Fox, Chair of Mechanical and Chemical Engineering; Dr. B. J. Bluth for her excellent comments on human factors; Dr. B. J. Campbell for improving the clarity; Richard Swaim, design engineer at Rocketdyne Division of Rockwell International for providing excellent engineering drawings of LEOBC; Mike Morrow, of the Advanced Engineering Department at Rockwell International who provided the Low Earth Orbit Business Center panel figures; Bob Bovill, a commercial artist, who did all the artistic drawings because of his interest in space commercialization; Linda Martin for her word processing skills; my wife, Yolanda, for egging me on without nagging; and finally Erik and Danielle for putting up with the excuse, "I have to v10rk on my paper," for too many years. iv 0 ' PREFACE The Low Earth Orbit Business Center (LEOBC) was initially conceived as a modular structure to be launched aboard the Space Shuttle, it evolved to its present configuration as a result of research, discussions and the desire to increase the efficiency of space utilization. Although the idea of placing space stations into Earth orbit is not new, as is discussed in the first chapter, and the configuration offers nothing new, LEOBC is unique in its application. -

Representations and Caricatures of Spanish Fascism in the Films El Espiritú De La Colmena, Cría Cueros and El Laberinto Del Fauno

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Winter 12-15-2014 Making Fun of Franco: Representations and Caricatures of Spanish Fascism in the films El espiritú de la colmena, Cría cueros and El laberinto del fauno Elizabeth Pruchnicki Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Other Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Pruchnicki, Elizabeth, "Making Fun of Franco: Representations and Caricatures of Spanish Fascism in the films El espiritú de la colmena, Cría cueros and El laberinto del fauno" (2014). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 866. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/866 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Making Fun of Franco: Representations and Caricatures of Spanish Fascism in the Films El espiritú de la colmena, Cría cueros and El laberinto del fauno A Capstone Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Renée Crown University Honors Program at Syracuse University Elizabeth Pruchnicki Candidate for Bachelor of Arts and Renée Crown University Honors May 2015 Honors Capstone Project in Spanish Capstone Project Advisor: Catherine M. Nock Capstone Project Reader: Kathryn Everly Honors Director: Stephen Kuusisto, Director Date: December 12, 2014 Making Fun of Franco: Representations and Caricatures of Spanish Fascism in the Films El espiritú de la colmena, Cría cueros and El laberinto del fauno. -

Elysium & Avatar

DOI: 10.32001/sinecine.741686 • Araştırma Makalesi | Research Article BETWEEN GREEN PARADISE AND BLEAK CALAMITY: ELYSIUM & AVATAR Cenk Tan Abstract Literary utopias and dystopias reflect a wide variety of concerns, from class and gender issues to the environment. These works not only reflect current social matters but also provide a glimpse of possible futures and a warning of perils to come. This article analyzes two science fiction films that have been in the spotlight during the last decade: Elysium (Neill Blomkamp, 2013) and Avatar (James Cameron, 2009). The two films depict disparate, dystopian visions of humanity’s future, yet both center on the themes of colonialism and the exploitation of the natural environment and offer ambiguous, open-ended conclusions. Focusing on these themes, this study applies postcolonial ecocriticism to expose the relationship between colonialism and ecocriticism and to show that the subtexts of both films deliver messages about the irrevocable destruction of the natural environment as an unconditional result of colonialism, impressing upon viewers the urgent need to adopt and implement an ecocentric mentality that will lead humanity to a peaceful and sustainable future. Keywords: Elysium, Avatar, Utopian/Dystopian fiction, film studies, postcolonial ecocriticism. Geliş Tarihi | Received: 23.05.2020 • Kabul Tarihi | Accepted: 14.09.2020 30 Eylül 2020 Tarihinde Online Olarak Yayınlanmıştır. Öğr. Gör. Dr., Pamukkale Üniversitesi Yabancı Diller Yüksekokulu ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2451-3612 • E-Posta: [email protected] Tan, C. (2020). Between Green Paradise and Bleak Calamity: Elysium & Avatar. sinecine, 11(2), 301-323. YEŞIL CENNETLE KASVETLI FELAKET ARASINDA: ELYSIUM & AVATAR Öz Ütopya/distopya yazını sınıf mücadelesinden, cinsiyet ve çevre sorunlarına kadar sosyal konuları ele almaktadır. -

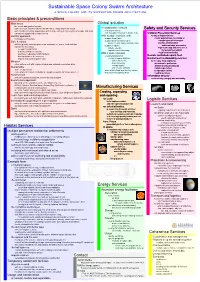

Sustainable Space Colony Swarm Architecture

Sustainable Space Colony Swarm Architecture A SPACE COLONY AND ITS SUPPORTING SWARM ARCHITECTURE Basic principles & preconditions Main focus Global solution the needs and goals of people sufficient room and the natural habitat that our body and mind needs A collaborative network Safety and Security Services with a sufficiently large population, with a large variety in ages, types of people and skills of a space colony extensively supported on many levels and its supporting swarm architecture Collision Prevention Services Holistic approach With multiple habitats, with for object impact defense, multi-layer architecture support from Earth mostly autonomous, consisting of Safe & robust support from celestial bodies: multiple types of telescopes Moon, Venus, Mars and Asteroids distributed information artificial gravity, radiation protection, atmosphere, water, food and light support in space: and knowledge processing robustness by default: safety, energy, flight vector adjustment services, compartmentalization, logistics, manufacturing by autonomous unit(s) distributed implementation, cloud overblow facility multilayer redundancy with fallback, With a space armada backup facilities & resources at Lagrangian points: Remote controlled repairs fleet impact and collision prevention clouds of space stations, Environment sustainability services with settlements, Mindset for humans, flora and fauna manufacturing, either safe or not, with regular internal and external evacuation drills air and water purification energy supply artificial gravity provisioning