Reading for Fictional Worlds in Literature and Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Exhibits Registrations

July ‘09 EXHIBITS In the Main Gallery MONDAY TUESDAY SATURDAY ART ADVISORY COUNCIL MEMBERS’ 6 14 “STREET ANGEL” (1928-101 min.). In HYPERTENSION SCREENING: Free 18 SHOW, throughout the summer. AAC MANHASSET BAY BOAT TOURS: Have “laughter-loving, careless, sordid Naples,” screening by St. Francis Hospital. 11 a.m. a look at Manhasset Bay – from the water! In the Photography Gallery a fugitive named Angela (Oscar winner to 2 p.m. A free 90-minute boat tour will explore Janet Gaynor) joins a circus and falls in Legendary Long the history and ecology of our corner of love with a vagabond painter named Gino TOPICAL TUESDAY: Islanders. What do Billy Joel, Martha Stew- Long Island Sound. Tour dates are July (Charles Farrell). Philip Klein and Henry art, Kiri Te Kanawa and astronaut Dr. Mary 18; August 8 and 29. The tour is free, but Roberts Symonds scripted, from a novel Cleave have in common? They have all you must register at the Information Desk by Monckton Hoffe, for director Frank lived on Long Island and were interviewed for the 30 available seats. Registration for Borzage. Ernest Palmer and Paul Ivano by Helene Herzig when she was feature the July 18 tour begins July 2; Registration provided the glistening cinematography. editor of North Shore Magazine. Herzig has for the August tours begins July 21. Phone Silent with orchestral score. 7:30 p.m. collected more than 70 of her interviews, registration is acceptable. Tours at 1 and written over a 20-year period. The celebri- 3 p.m. Call 883-4400, Ext. -

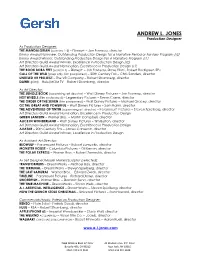

JONES-A.-RES-1.Pdf

ANDREW L. JONES Production Designer As Production Designer: THE MANDALORIAN (seasons 1-3) – Disney+ – Jon Favreau, director Emmy Award Nominee, Outstanding Production Design for a Narrative Period or Fantasy Program (s2) Emmy Award Winner, Outstanding Production Design For A Narrative Program (s1) Art Directors Guild Award Winner, Excellence in Production Design (s2) Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design (s1) THE BOOK BOBA FETT (season 1) – Disney+ – Jon Favreau, Dave Filoni, Robert Rodriguez, EPs CALL OF THE WILD (prep only, film postponed) – 20th Century Fox – Chris Sanders, director UNTITLED VR PROJECT – The VR Company – Robert Stromberg, director DAWN (pilot) – Hulu/MGM TV – Robert Stromberg, director As Art Director: THE JUNGLE BOOK (supervising art director) – Walt Disney Pictures – Jon Favreau, director HOT WHEELS (film postponed) – Legendary Pictures – Simon Crane, director THE ORDER OF THE SEVEN (film postponed) – Walt Disney Pictures – Michael Gracey, director OZ THE GREAT AND POWERFUL – Walt Disney Pictures – Sam Raimi, director THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN (supervising art director) – Paramount Pictures – Steven Spielberg, director Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design GREEN LANTERN – Warner Bros. – Martin Campbell, director ALICE IN WONDERLAND – Walt Disney Pictures – Tim Burton, director Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design AVATAR – 20th Century Fox – James Cameron, director Art Directors Guild Award Winner, Excellence in Production Design As Assistant Art Director: BEOWULF – Paramount Pictures – Robert Zemeckis, director MONSTER HOUSE – Columbia Pictures – Gil Kenan, director THE POLAR EXPRESS – Warner Bros. – Robert Zemeckis, director As Set Designer/Model Maker/Sculptor (selected): TRANSFORMERS – DreamWorks – Michael Bay, director THE TERMINAL – DreamWorks – Steven Spielberg, director THE LAST SAMURAI – Warner Bros. -

Thematic, Moral and Ethical Connections Between the Matrix and Inception

Thematic, Moral and Ethical Connections Between the Matrix and Inception. Modern Day science and technology has been crucial in the development of the modern film industry. In the past, directors have been confined by unwieldy, primitive cameras and the most basic of special effects. The contemporary possibilities now available has enabled modern film to become more dynamic and versatile, whilst also being able to better capture the performance of actors, and better display scenes and settings using special effects. As the prevalence of technology in society increases, film makers have used their medium to express thematic, moral and ethical concerns of technology in human life. The films I will be looking at: The Matrix, directed by the Wachowskis, and Inception, directed by Christopher Nolan, both explore strong themes of technology. The theme of technology is expanded upon as the directors of both films explore the use of augmented reality and its effects on the human condition. Through the use of camera angles, costuming and lighting, the Witkowski brothers represent the idea that technology is dangerous. During the sequence where neo is unplugged from the Matrix, the directors have cleverly combines lighting, visual and special effects to craft an ominous and unpleasant setting in which the technology is present. Upon Neo’s confrontation with the spider drone, the use of camera angles to establishes the dominance of technology. The low-angle shot of the drone places the viewer in a subordinate position, making the drone appear powerful. The dingy lighting and poor mis-en-scene in the set further reinforces the idea that technology is dangerous. -

Guillermo Del Toro’S Bleak House

GuillermoAt Home With Monstersdel Toro By James Balestrieri Guillermo del Toro’s Bleak House. Photo ©Josh White/ JWPictures.com. LOS ANGELES, CALIF. — The essence of “Guillermo del Toro: At Home With Monsters,” the strange and wonderful exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) through November 27, is this: Guillermo del Toro, born in 1964, is a major writer and director whose films include Cronos (1993), The Devil’s Backbone (2001), Hellboy (2004), Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), Pacific Rim (2013) and Crimson Peak (2015). He is a master who creates worlds that embrace horror, science fiction, fantasy and fairy tales. He insists that, as fantastic as they are, these worlds are located and grounded beside, beneath and in the real world, our world — a world, he might argue, that we merely imagine as real. The membrane separating these worlds is thin, porous and portal-ridden. The worlds are distorted reflections of one another. This distortion becomes the occasion for his ideas and art. Page from Notebook 2 by Guillermo del Toro. Leather-bound notebook, ink on paper, 8 by 10 by 1½ inches. Collection of Guillermo del Toro. ©Guillermo del Toro. Photo courtesy Insight Editions. Jointly organized by LACMA with the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the Art Gallery of Ontario, this first retrospective of the filmmaker’s work arrays sculpture, paintings, prints, photography, costumes, ancient artifacts, books, maquettes and film to create a complex portrait of a creative genius. Roughly 60 of the 500 objects on view are from LACMA’s collection. More belong to the artist. -

L3700 LETHAL WEAPON (USA, 1987) (Other Titles: Arma Lethale; Arme Fatale; Dodbringende Veben; Zwei Stahlharte Profis)

L3700 LETHAL WEAPON (USA, 1987) (Other titles: Arma lethale; Arme fatale; Dodbringende veben; Zwei stahlharte profis) Credits: director, Richard Donner ; writer, Shane Black. Cast: Mel Gibson, Danny Glover, Gary Busey. Summary: Police thriller set in contemporary Los Angeles. Martin Riggs (Gibson) is no ordinary cop. He is a Vietnam veteran whose killing expertise and suicidal recklessness make him a lethal weapon to anyone he works against or with. Roger Murtaugh (Glover), also a veteran, is an easy-going homicide detective with a loving family, a big house, and a pension he does not want to lose. The only thing Murtaugh and Riggs have in common is that they hate to work with partners, but their partnership becomes the key to survival when a routine murder investigation turns into an all-out war with an international heroin ring. Ansen, David. “The arts: Movies: Urban Rambo” Newsweek 109 (May 16, 1987), p. 72. [Reprinted in Film review annual 1988] “L’Arme fatale” Cine-tele-revue 31 (Jul 30, 1987), p. 16-19. Boedeker, Hal. “Lethal weapon wastes Mel Gibson” Miami herald (Mar 6, 1987), p. 5D. Canby, Vincent. “Film view: Gun movies: Big bore and small caliber” New York times 136 (May 10, 1987), sec. 2, p. 17. Carr, Jay. “‘Lethal weapon’ is high-energy bullet ballet” Boston globe (Mar 6, 1987), Arts and film, p. 36. Christensen, Johs H. “Dodbringende veben” Levende billeder 3 (Sep 1, 1987), p. 51. Cunneff, T. [Lethal weapon] People weekly 27 (Mar 23, 1987), p. 8. Darnton, Nina. “At the movies: A new hit has the industry asking why” New York times 136 (Apr 3, 1987), p. -

Editorial Necsus

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES www.necsus-ejms.org Editorial Necsus NECSUS 6 (2), Autumn 2017: 1–3 URL: https://necsus-ejms.org/editorial-necsus-autumn-2017/ Keywords: dress, editorial From the early days of film studies, costumes have been analysed as an im- portant element of the mise-en-scène and stardom, as they help shape identi- ties and define subjectivities, crafting the stars. There is no question that cos- tumes help create meaning, no less today than in the heyday of classical cin- ema. More recently, haute couture has entered film as a topic, just as fashion designers have become the subjects of biopics. In recent years, fashion films have become an interesting vehicle for large fashion brands that were able to attract prestigious auteurs (Roman Polanski, Wes Anderson, Martin Scorsese, Sofia Coppola, et al). Indeed, the whole ecosystem of fashion has been rup- tured by the effects of digital distribution, blogs, and social media. The special section of the Autumn 2017 issue of NECSUS is devoted to this key element in photographic practices and cinematic and audiovisual storytelling. #Dress investigates fashion and costume as theoretical and ana- lytical concerns in media studies, and the analyses demonstrate how dress and costume contribute to the production of meaning. #Dress also presents the many echoes of Roland Barthes’ seminal publication The Fashion System (1967) and the ‘language’ of fashion magazines as an analytical tool to address theoretical questions of identity, politics, and cultural history. Contributors to this special section include Marie Lous Baronian, Giuliana Bruno, Isabelle Freda, Šárka Gmiterková & Miroslava Papežová, and Frances Joseph. -

Executive Producer)

PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES STEVEN SODERBERGH (Executive Producer) Steven Soderbergh has produced or executive-produced a wide range of projects, most recently Gregory Jacobs' Magic Mike XXL, as well as his own series "The Knick" on Cinemax, and the current Amazon Studios series "Red Oaks." Previously, he produced or executive-produced Jacobs' films Wind Chill and Criminal; Laura Poitras' Citizenfour; Marina Zenovich's Roman Polanski: Odd Man Out, Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, and Who Is Bernard Tapie?; Lynne Ramsay's We Need to Talk About Kevin; the HBO documentary His Way, directed by Douglas McGrath; Lodge Kerrigan's Rebecca H. (Return to the Dogs) and Keane; Brian Koppelman and David Levien's Solitary Man; Todd Haynes' I'm Not There and Far From Heaven; Tony Gilroy's Michael Clayton; George Clooney's Good Night and Good Luck and Confessions of a Dangerous Mind; Scott Z. Burns' Pu-239; Richard Linklater's A Scanner Darkly; Rob Reiner's Rumor Has It...; Stephen Gaghan'sSyriana; John Maybury's The Jacket; Christopher Nolan's Insomnia; Godfrey Reggio's Naqoyqatsi; Anthony and Joseph Russo's Welcome to Collinwood; Gary Ross' Pleasantville; and Greg Mottola's The Daytrippers. LODGE KERRIGAN (Co-Creator, Executive Producer, Writer, Director) Co-Creators and Executive Producers Lodge Kerrigan and Amy Seimetz wrote and directed all 13 episodes of “The Girlfriend Experience.” Prior to “The Girlfriend Experience,” Kerrigan wrote and directed the features Rebecca H. (Return to the Dogs), Keane, Claire Dolan and Clean, Shaven. His directorial credits also include episodes of “The Killing” (AMC / Netflix), “The Americans” (FX), “Bates Motel” (A&E) and “Homeland” (Showtime). -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

Space, Vision, Power, by Sean Carter and Klaus Dodds. Wallflower, 2014, 126 Pp

Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media no. 21, 2021, pp. 228–234 DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.21.19 International Politics and Film: Space, Vision, Power, by Sean Carter and Klaus Dodds. Wallflower, 2014, 126 pp. Juneko J. Robinson Once, there were comparatively few books that focused on the relationship between international politics and film. Happily, this is no longer the case. Sean Carter and Klaus Dodd’s International Politics and Film: Space, Vision, Power is an exciting addition to the growing body of literature on the political ontology of art and aesthetics. As scholars in geopolitics and human geography, their love for film is evident, as is their command of the interdisciplinary literature. Despite its brevity, this well-argued and thought-provoking book covers an impressive 102 films from around the world, albeit some in far greater detail than others. Still, despite its compactness, it is a satisfying read that will undoubtedly attract casual readers unfamiliar with scholarship in either discipline but with enough substance to delight specialists in both film and international relations. Carter and Dodds successfully bring international relations (IR) and critical geopolitics into closer alignment with visual studies in general and film studies in particular. Their thesis is simple: first, the traditional emphasis of IR on macro-level players such as heads of state, diplomats, the intelligence community, and intergovernmental organisations such as the United Nations have created a biased perception of what constitutes the practice of international politics. Second, this bias is problematic because concepts such as the state and the homeland, amongst others, are abstract entities whose ontological statuses do not exist apart from the practices of people. -

FILMS MANK Makeup Artist Netflix Director: David Fincher SUN DOGS

KRIS EVANS Member Academy of Makeup Artist Motion Picture Arts and Sciences IATSE 706, 798 and 891 BAFTA Los Angeles [email protected] (323) 251-4013 FILMS MANK Makeup Artist Netflix Director: David Fincher SUN DOGS Makeup Department Head Fabrica De Cine Director: Jennifer Morrison Cast: Ed O’Neill, Allison Janney, Melissa Benoist, Michael Angarano FREE STATE OF JONES Key Makeup STX Entertainment Director: Gary Ross Cast: Mahershala Ali, Matthew McConaughey, GuGu Mbatha-Raw THE PERFECT GUY Key Makeup Screen Gems Director: David M Rosenthal Cast: Sanaa Lathan, Michael Ealy, Morris Chestnut NIGHTCRAWLER Key Makeup, Additional Photography Bold Films Director: Dan Gilroy HUNGER GAMES MOCKINGJAY PART 1 & 2 Background Makeup Supervisor Lionsgate Director: Francis Lawrence THE HUNGER GAMES: CATCHING FIRE Background Makeup Supervisor Lionsgate Director: Francis Lawrence THE FACE OF LOVE Assistant Department Head Mockingbird Pictures Director: Arie Posen THE RELUCTANT FUNDAMENTALIST Makeup Department Head Cine Mosaic Director: Mira Nair Cast: Riz Ahmed, Kate Hudson, Kiefer Sutherland ABRAHAM LINCOLN VAMPIRE HUNTER 2012 Special Effects Makeup Artists th 20 Century Fox Director: Timur Bekmambetov THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 2012 Makeup Artist Columbia Pictures Director: Marc Webb THE HUNGER GAMES Background Makeup Supervisor Lionsgate Director: Gary Ross THE RUM DIARY Key Makeup Warner Independent Pictures Director: Bruce Robinson Cast: Amber Heard, Giovanni Ribisi, Amaury Nolasco, Richard Jenkins 1 KRIS EVANS Member Academy of Makeup Artist -

January 2012 at BFI Southbank

PRESS RELEASE November 2011 11/77 January 2012 at BFI Southbank Dickens on Screen, Woody Allen & the first London Comedy Film Festival Major Seasons: x Dickens on Screen Charles Dickens (1812-1870) is undoubtedly the greatest-ever English novelist, and as a key contribution to the worldwide celebrations of his 200th birthday – co-ordinated by Film London and The Charles Dickens Museum in partnership with the BFI – BFI Southbank will launch this comprehensive three-month survey of his works adapted for film and television x Wise Cracks: The Comedies of Woody Allen Woody Allen has also made his fair share of serious films, but since this month sees BFI Southbank celebrate the highlights of his peerless career as a writer-director of comedy films; with the inclusion of both Zelig (1983) and the Oscar-winning Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) on Extended Run 30 December - 19 January x Extended Run: L’Atalante (Dir, Jean Vigo, 1934) 20 January – 29 February Funny, heart-rending, erotic, suspenseful, exhilaratingly inventive... Jean Vigo’s only full- length feature satisfies on so many levels, it’s no surprise it’s widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made Featured Events Highlights from our events calendar include: x LoCo presents: The London Comedy Film Festival 26 – 29 January LoCo joins forces with BFI Southbank to present the first London Comedy Film Festival, with features previews, classics, masterclasses and special guests in celebration of the genre x Plus previews of some of the best titles from the BFI London Film Festival: