Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning with Anne: Jason Nolan � 8/14/09 4:13 PM Deleted: Chapter Seven Early Childhood Education Looks at New Media for Young Girls

Learning with Anne: Jason Nolan ! 8/14/09 4:13 PM Deleted: Chapter Seven Early Childhood Education Looks at New Media for Young Girls Forthcoming in: Gammel, I. and Lefebvre, B. (Eds.) Anne of Green Gables: New Directions at 100. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Jason Nolan, PhD School of Early Childhood Education Ryerson University Here, too, the ethical responsibility of the school on the social side must be interpreted in the broadest and freest spirit; it is equivalent to that training of the child which will give him such possession of himself that he may take charge of himself; may not only adapt himself to the changes that are going on, but have power to shape and direct them. -- John Dewey1 In L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Avonlea (1909), sixteen-year-old Anne Shirley articulates a progressive pedagogical attitude that seems to coincide with Dewey’s Moral Principles in Education, published the same year: ‘No, if I can’t get along without whipping I shall not try to teach school. There are better ways of managing. I shall try to win my pupils’ affections and then they will want to do what I tell them.’2 Drawing from her own childhood experience depicted in Anne of Green Gables, fledgling teacher Anne describes a schooling experience that would treat the student as she once wished to be treated. As a child, Anne embodied the model of a self-directed learner who actively engaged with her physical and social environment, making meaning and constructing her own identity and understanding of the world, indeed creating a world in which she could live. -

A Third Wave Feminist Re-Reading of Anne of Green Gables Maria Virokannas University of Tampere English

The Complex Anne-Grrrl: A Third Wave Feminist Re-reading of Anne of Green Gables Maria Virokannas University of Tampere English Philology School of Modern Languages and Translation Studies Tampereen yliopisto Englantilainen filologia Kieli- ja käännöstieteenlaitos Virokannas, Maria: The Complex Anne-Grrrl: A Third Wave Feminist Re-reading of Anne of Green Gables Pro gradu -tutkielma, 66 sivua + lähdeluettelo Syksy 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Tämän pro gradu -tutkielman tavoitteena oli selvittää voidaanko Lucy Maud Montgomeryn 1908 ilmestyneestä romaanista Anne of Green Gables löytää kolmannen aallon feminismin piirteitä. Erityisesti tutkin löytyykö romaanista piirteitä ristiriitaisuudesta ja sen omaksumisesta ja individualismin ideologiasta, feministisestä ja positiivisesta äitiydestä sekä konventionaalisen naisellisuuden etuoikeuttamisesta. Tutkielmani teoreettinen kehys muodostuu feministisestä kirjallisuuden tutkimuksesta, painottuen kolmannen aallon feministiseen teoriaan. Erityisesti feminististä äitiyttä tutkittaessa tutkielman kulmakivenä on Adrienne Richin teoria äitiydestä, jota Andrea O'Reilly on kehittänyt. Tämän teorian mukaan äitiys on toisaalta miesten määrittelemä ja kontrolloima, naista alistava instituutio patriarkaalisessa yhteiskunnassa, toisaalta naisten määrittelemä ja naiskeskeinen positiivinen elämys, joka potentiaalisesti voimauttaa naisia. Kolmannen aallon feminismi korostaa eroja naisten välillä ja naisissa itsessään, -

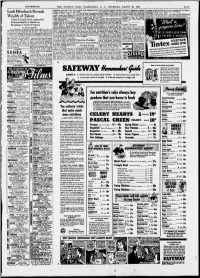

SAFEWAY Timmalm-(Juuu

tecehnique made light of the for- the latter works following the Pro- bussy’s ‘‘Reverie,’* Campos’ "Gloria” disclosed In Schumann's “Quintet" by Lvovsky, as well as works by the is an a cappella choir and sings en- midable passage work of the first kofleff. and Sarasate's ‘‘Navarra,” the last a fine understanding of his respon- outstanding choral writers, F. Melius tirely from memory. Leah Effenbach Reveals The performance of the three Don Jesus Fi- sibilities towards the strings and Christiansen, Noble Cain, Allan movement which gldSved with symphony arranged by was one of those rewarding in- gueroa, head of the family and how to blend and to atune the piano Murray, Mortan Luvaas, Hall John- Uncle Sam ran nse this newspaper healthy vitality in her brilliant de- stances when the very essence of conductor and composer In his own to them. All five young men show son and others. The Concert Choir when you’ve finished reading it. livery. in the second movement a Wealth of Talent the work is brought out with ex- right. musicanship and an excellent warm tone and rich musical singing ceptional Insight. Built up emo- It was rather unusual that the schooling. A good size audience, feeling were disclosed. Gifted Young Pianist Applauded tionally in gripping fashion. Dr. playing of the group was free from hearing their local debut, was The Prokofiefl concerto is an Kindler’s reading was beautifully blemishes, often Inevitable in family responsive. Enthusiastically as Soloist on amazing work both in its pianistic varied in nuance and color. The groups where the less capable or demands and in its revelation of gay overture, the amusing excerpt advanced are made to fit into the Varied another angle of the composer’s from Shostakovich’s “The Golden picture. -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Friday the 13Th Part II by Simon Hawke Friday the 13Th Part 2 Review

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Friday the 13th Part II by Simon Hawke Friday the 13th part 2 review. Vickie didnt want to disturb Jeff and Sandra. She had heard the vigorous sounds coming from their bedroom, and knew they must be lying exhausted in each others arms by now. But she had to see them. She had to warn them what was happening here at Crystal Lake, as thunder crashed and lightning flashed. Timidly she opened the bedroom door and looked inside. The sheets were pulled over two figures lying on the bed. Sandra, Vickie whispered. Then the sheet was thrown back, and a hooded figure sat up. and Vickie screamed and screamed and screamed. Dr. Wolfula- "Friday the 13th Part 2" Review. User Reviews. Check out what Sophie had to say about the corresponding Freddy pic here! With Mrs. Voorhees with no head and a cliffhanger of an ending, writer Ron Kurz and director Steve Miner had a few roads to travel in unraveling more of the slasher franchise. The camp slasher foundation continues its build, but the introduction of a soon to be iconic killer makes the film feel fresh and exciting with a surprising attention to detail. Alice Hardy has survived the attacks of crazy Mrs. Voorhees and decides to gain back her normalcy in a summer vacation home. The dream of a decomposed young Jason still haunt her, as does the head of Pamela flying from her neck. Forgot your password? Don't have an account? Sign up here. By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and Fandango. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

THE DARK PAGES the Newsletter for Film Noir Lovers Vol

THE DARK PAGES The Newsletter for Film Noir Lovers Vol. 6, Number 1 SPECIAL SUPER-SIZED ISSUE!! January/February 2010 From Sheet to Celluloid: The Maltese Falcon by Karen Burroughs Hannsberry s I read The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiell Hammett, I decide on who will be the “fall guy” for the murders of Thursby Aactually found myself flipping more than once to check and Archer. As in the book, the film depicts Gutman giving Spade the copyright, certain that the book couldn’t have preceded the an envelope containing 10 one-thousand dollar bills as a payment 1941 film, so closely did the screenplay follow the words I was for the black bird, and Spade hands it over to Brigid for safe reading. But, to be sure, the Hammett novel was written in 1930, keeping. But when Brigid heads for the kitchen to make coffee and the 1941 film was the third of three features based on the and Gutman suggests that she leave the cash-filled envelope, he book. (The first, released in 1931, starred Ricardo Cortez and announces that it now only contains $900. Spade immediately Bebe Daniels, and the second, the 1936 film, Satan Met a Lady, deduces that Gutman palmed one of the bills and threatens to was a light comedy with Warren William and Bette Davis.) “frisk” him until the fat man admits that Spade is correct. But For my money, and for most noirists, the 94 version is the a far different scene played out in the book where, when the definitive adaptation. missing bill is announced, Spade ushers Brigid The 1941 film starred Humphrey Bogart into the bathroom and orders her to strip naked as private detective Sam Spade, along with to prove her innocence. -

A History of Looking.’

GETTING IN ON THE ACT ‘A History of Looking.’ Volume 1. Nichola Cecelia Bird Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD University of Leeds Department of Fine Art September 1998 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. Abstract My research has been a form of retrieval with the starting point often being an original or ‘found’ photograph. I am interested in how ‘documentary’ photography, whether by accident or design, catches and preserves the peripheral. I have been working with a series of ‘historical’ photographs, in which an unidentified individual or group who are ‘peripheral’ to the main point of the photograph, have been ‘caught’ within its frame. The retrieval is in using those ‘unassumed’ parts of the ‘found’ photograph, so they become another source of meaning. The theme of ‘the periphery’ has become the basis for my research, resulting in both artworks and writings. For example, the installation The Fitting and the text A History of Looking are based on a little known photograph of Marilyn Monroe watched by a group of unidentified women. Both outcomes are different kinds of ‘close readings’ of the original image. While the installation is concerned with image, viewer and space, the text investigates the process of memory and speculation; how ‘photography’, 'autobiography’ and ‘history’ are also embroiled with aspects of femininity, consumption and nostalgia. An investigation of an original photograph can take two routes: one in which the camera documents the process or journey – collecting evidence of possible traces of places or people. -

Representation of Lesbian Images in Films

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2003 Women in the dark: representation of lesbian images in films Hye-Jin Lee Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Lee, Hye-Jin, "Women in the dark: representation of lesbian images in films" (2003). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 19470. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/19470 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. women in the dark: Representation of lesbian images in films by Hye-Jin Lee A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Program of Study Committee: Tracey Owens Patton, Major Professor Jill Bystydzienski Cindy Christen Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2003 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Hye-Jin Lee has met the thesis requirement of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: REVIEW OF LITERATURE The Importance of Studying Films 4 Homosexuality and -

Doherty, Thomas, Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, Mccarthyism

doherty_FM 8/21/03 3:20 PM Page i COLD WAR, COOL MEDIUM TELEVISION, McCARTHYISM, AND AMERICAN CULTURE doherty_FM 8/21/03 3:20 PM Page ii Film and Culture A series of Columbia University Press Edited by John Belton What Made Pistachio Nuts? Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic Henry Jenkins Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition of Spectacle Martin Rubin Projections of War: Hollywood, American Culture, and World War II Thomas Doherty Laughing Screaming: Modern Hollywood Horror and Comedy William Paul Laughing Hysterically: American Screen Comedy of the 1950s Ed Sikov Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography, and Contemporary Chinese Cinema Rey Chow The Cinema of Max Ophuls: Magisterial Vision and the Figure of Woman Susan M. White Black Women as Cultural Readers Jacqueline Bobo Picturing Japaneseness: Monumental Style, National Identity, Japanese Film Darrell William Davis Attack of the Leading Ladies: Gender, Sexuality, and Spectatorship in Classic Horror Cinema Rhona J. Berenstein This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in the Jazz Age Gaylyn Studlar Sexual Politics and Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond Robin Wood The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music Jeff Smith Orson Welles, Shakespeare, and Popular Culture Michael Anderegg Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, ‒ Thomas Doherty Sound Technology and the American Cinema: Perception, Representation, Modernity James Lastra Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts Ben Singer -

NBC Presents Kristin Chenoweth's

July 13 - 19, 2018 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad A M F S A Y P Y K A O R B S A 2 x 3" ad Q U S L W N U E A S T P E C K Your Key A R J L A V I N I A C D I O I To Buying G D A Y O M E J H D W A Y N E 2 x 3.5" ad V E K N W U B T A T R G X W N and Selling! U R T N A L E O L K M O V A H B O Y E R W S N Y T Z S E N Y L I W G O M H L C A H T U N I A I R N G W E O W V N O S E P F J E C V B P C L Y W T R L D I H O A J S H K A S M E S B O C X Y S Q U E P V R Y H M A E V F D C H O R F I W O V A D R A N W A M Y D R A X S L Y I R H P E H A I R L E S S E S O Z “Trial and Error” on NBC Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Lavinia (Peck-Foster) (Kristin) Chenoweth (New York) Lawyer Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Josh (Segal) (Nicholas) D’Agosto (Bizarre) Murder ad in the Waxahachie Daily Merchandise High-End Dwayne (Reed) (Steven) Boyer East Peck 2 x 3" ad Light, Midlothian1 x Mirror 4" ad and Deal Merchandise Carol (Anne Keane) (Jayma) Mays Flamboyant (Outfits) Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search Anne (Flatch) (Sherri) Shepherd Hairless (Cat) Call (972) 937-3310 NBC presents Run a single item Run a single item © Zap2it priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week Kristin Chenoweth’s 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light, 3.5" ad Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post Kristin Chenoweth stars in Season 2 of “Trial & Error,” and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid.