LESSON 5: LEAVES and TREES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant Terminology

PLANT TERMINOLOGY Plant terminology for the identification of plants is a necessary evil in order to be more exact, to cut down on lengthy descriptions, and of course to use the more professional texts. I have tried to keep the terminology in the database fairly simple but there is no choice in using many descriptive terms. The following slides deal with the most commonly used terms (more specialized terms are given in family descriptions where needed). Professional texts vary from fairly friendly to down-right difficult in their use of terminology. Do not be dismayed if a plant or plant part does not seem to fit any given term, or that some terms seem to be vague or have more than one definition – that’s life. In addition this subject has deep historical roots and plant terminology has evolved with the science although some authors have not. There are many texts that define and illustrate plant terminology – I use Plant Identification Terminology, An illustrated Glossary by Harris and Harris (see CREDITS) and others. Most plant books have at least some terms defined. To really begin to appreciate the diversity of plants, a good text on plant systematics or Classification is a necessity. PLANT TERMS - Typical Plant - Introduction [V. Max Brown] Plant Shoot System of Plant – stem, leaves and flowers. This is the photosynthetic part of the plant using CO2 (from the air) and light to produce food which is used by the plant and stored in the Root System. The shoot system is also the reproductive part of the plant forming flowers (highly modified leaves); however some plants also have forms of asexual reproduction The stem is composed of Nodes (points of origin for leaves and branches) and Internodes Root System of Plant – supports the plant, stores food and uptakes water and minerals used in the shoot System PLANT TERMS - Typical Perfect Flower [V. -

Transcript Profiling of a Novel Plant Meristem, the Monocot Cambium

Journal of Integrative JIPB Plant Biology Transcript profiling of a novel plant meristem, the monocot cambiumFA Matthew Zinkgraf1,2, Suzanne Gerttula1 and Andrew Groover1,3* 1. US Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Davis, California, USA 2. Department of Computer Science, University of California, Davis, USA 3. Department of Plant Biology, University of California, Davis, USA Article *Correspondence: Andrew Groover ([email protected]) doi: 10.1111/jipb.12538 Abstract While monocots lack the ability to produce a xylem tissues of two forest tree species, Populus Research vascular cambium or woody growth, some monocot trichocarpa and Eucalyptus grandis. Monocot cambium lineages evolved a novel lateral meristem, the monocot transcript levels showed that there are extensive overlaps cambium, which supports secondary radial growth of between the regulation of monocot cambia and vascular stems. In contrast to the vascular cambium found in woody cambia. Candidate regulatory genes that vary between the angiosperm and gymnosperm species, the monocot monocot and vascular cambia were also identified, and cambium produces secondary vascular bundles, which included members of the KANADI and CLE families involved have an amphivasal organization of tracheids encircling a in polarity and cell-cell signaling, respectively. We suggest central strand of phloem. Currently there is no information that the monocot cambium may have evolved in part concerning the molecular genetic basis of the develop- through reactivation of genetic mechanisms involved in ment or evolution of the monocot cambium. Here we vascular cambium regulation. report high-quality transcriptomes for monocot cambium Edited by: Chun-Ming Liu, Institute of Crop Science, CAAS, China and early derivative tissues in two monocot genera, Yucca Received Feb. -

Synthetic Conversion of Leaf Chloroplasts Into Carotenoid-Rich Plastids Reveals Mechanistic Basis of Natural Chromoplast Development

Synthetic conversion of leaf chloroplasts into carotenoid-rich plastids reveals mechanistic basis of natural chromoplast development Briardo Llorentea,b,c,1, Salvador Torres-Montillaa, Luca Morellia, Igor Florez-Sarasaa, José Tomás Matusa,d, Miguel Ezquerroa, Lucio D’Andreaa,e, Fakhreddine Houhouf, Eszter Majerf, Belén Picóg, Jaime Cebollag, Adrian Troncosoh, Alisdair R. Ferniee, José-Antonio Daròsf, and Manuel Rodriguez-Concepciona,f,1 aCentre for Research in Agricultural Genomics (CRAG) CSIC-IRTA-UAB-UB, Campus UAB Bellaterra, 08193 Barcelona, Spain; bARC Center of Excellence in Synthetic Biology, Department of Molecular Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney NSW 2109, Australia; cCSIRO Synthetic Biology Future Science Platform, Sydney NSW 2109, Australia; dInstitute for Integrative Systems Biology (I2SysBio), Universitat de Valencia-CSIC, 46908 Paterna, Valencia, Spain; eMax-Planck-Institut für Molekulare Pflanzenphysiologie, 14476 Potsdam-Golm, Germany; fInstituto de Biología Molecular y Celular de Plantas, CSIC-Universitat Politècnica de València, 46022 Valencia, Spain; gInstituto de Conservación y Mejora de la Agrodiversidad, Universitat Politècnica de València, 46022 Valencia, Spain; and hSorbonne Universités, Université de Technologie de Compiègne, Génie Enzymatique et Cellulaire, UMR-CNRS 7025, CS 60319, 60203 Compiègne Cedex, France Edited by Krishna K. Niyogi, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved July 29, 2020 (received for review March 9, 2020) Plastids, the defining organelles of plant cells, undergo physiological chromoplasts but into a completely different type of plastids and morphological changes to fulfill distinct biological functions. In named gerontoplasts (1, 2). particular, the differentiation of chloroplasts into chromoplasts The most prominent changes during chloroplast-to-chromo- results in an enhanced storage capacity for carotenoids with indus- plast differentiation are the reorganization of the internal plastid trial and nutritional value such as beta-carotene (provitamin A). -

Tansley Review Evolution of Development of Vascular Cambia and Secondary Growth

New Phytologist Review Tansley review Evolution of development of vascular cambia and secondary growth Author for correspondence: Rachel Spicer1 and Andrew Groover2 Andrew Groover 1The Rowland Institute at Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA; 2Institute of Forest Genetics, Pacific Tel: +1 530 759 1738 Email: [email protected] Southwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Davis, CA, USA Received: 29 December 2009 Accepted: 14 February 2010 Contents Summary 577 V. Evolution of development approaches for the study 587 of secondary vascular growth I. Introduction 577 VI. Conclusions 589 II. Generalized function of vascular cambia and their 578 developmental and evolutionary origins Acknowledgements 589 III. Variation in secondary vascular growth in angiosperms 581 References 589 IV. Genes and mechanisms regulating secondary vascular 584 growth and their evolutionary origins Summary New Phytologist (2010) 186: 577–592 Secondary growth from vascular cambia results in radial, woody growth of stems. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03236.x The innovation of secondary vascular development during plant evolution allowed the production of novel plant forms ranging from massive forest trees to flexible, Key words: forest trees, genomics, Populus, woody lianas. We present examples of the extensive phylogenetic variation in sec- wood anatomy, wood formation. ondary vascular growth and discuss current knowledge of genes that regulate the development of vascular cambia and woody tissues. From these foundations, we propose strategies for genomics-based research in the evolution of development, which is a next logical step in the study of secondary growth. I. Introduction this pattern characterizes most extant forest trees, significant variation exists among taxa, ranging from extinct woody Secondary vascular growth provides a means of radially lycopods and horsetails with unifacial cambia (Cichan & thickening and strengthening plant axes initiated during Taylor, 1990; Willis & McElwain, 2002), to angiosperms primary, or apical growth. -

Non-Destructive Estimation of Root Pressure Using Sap Flow, Stem

Annals of Botany 111: 271–282, 2013 doi:10.1093/aob/mcs249, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org Non-destructive estimation of root pressure using sap flow, stem diameter measurements and mechanistic modelling Tom De Swaef*, Jochen Hanssens, Annelies Cornelis and Kathy Steppe Faculty of Bioscience Engineering, Department of Applied Ecology and Environmental Biology, Laboratory of Plant Ecology, Ghent University, Coupure links 653, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium * For correspondence. E-mail [email protected] Received: 20 August 2012 Returned for revision: 24 September 2012 Accepted: 8 October 2012 Published electronically: 4 December 2012 † Background Upward water movement in plants via the xylem is generally attributed to the cohesion–tension theory, as a response to transpiration. Under certain environmental conditions, root pressure can also contribute Downloaded from to upward xylem water flow. Although the occurrence of root pressure is widely recognized, ambiguity exists about the exact mechanism behind root pressure, the main influencing factors and the consequences of root pres- sure. In horticultural crops, such as tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), root pressure is thought to cause cells to burst, and to have an important impact on the marketable yield. Despite the challenges of root pressure research, progress in this area is limited, probably because of difficulties with direct measurement of root pressure, prompt- ing the need for indirect and non-destructive measurement techniques. http://aob.oxfordjournals.org/ † Methods A new approach to allow non-destructive and non-invasive estimation of root pressure is presented, using continuous measurements of sap flow and stem diameter variation in tomato combined with a mechanistic flow and storage model, based on cohesion–tension principles. -

Research Advances on Leaf and Wood Anatomy of Woody Species

rch: O ea pe es n A R t c s c Rodriguez et al., Forest Res 2016, 5:3 e e r s o s Forest Research F DOI: 10.4172/2168-9776.1000183 Open Access ISSN: 2168-9776 Research Article Open Access Research Advances on Leaf and Wood Anatomy of Woody Species of a Tamaulipan Thorn Scrub Forest and its Significance in Taxonomy and Drought Resistance Rodriguez HG1*, Maiti R1 and Kumari A2 1Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Carr. Nac. No. 85 Km. 45, Linares, Nuevo León 67700, México 2Plant Physiology, Agricultural College, Professor Jaya Shankar Telangana State Agricultural University, Polasa, Jagtial, Karimnagar, Telangana, India Abstract The present paper make a synthesis of a comparative leaf anatomy including leaf surface, leaf lamina, petiole and venation as well as wood anatomy of 30 woody species of a Tamaulipan Thorn Scrub, Northeastern Mexico. The results showed a large variability in anatomical traits of both leaf and wood anatomy. The variations of these anatomical traits could be effectively used in taxonomic delimitation of the species and adaptation of the species to xeric environments. For example the absence or low frequency of stomata on leaf surface, the presence of long palisade cells, and presence of narrow xylem vessels in the wood could be related to adaptation of the species to drought. Besides the species with dense venation and petiole with thick collenchyma and sclerenchyma and large vascular bundle could be well adapted to xeric environments. It is suggested that a comprehensive consideration of leaf anatomy (leaf surface, lamina, petiole and venation) and wood anatomy should be used as a basis of taxonomy and drought resistance. -

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

Mechanical Properties of Blueberry Stems

Vol. 64, 2018 (4): 202–208 Res. Agr. Eng. https://doi.org/10.17221/90/2017-RAE Mechanical properties of blueberry stems Margus Arak1, Kaarel Soots1*, Marge Starast2, Jüri Olt1 1Institute of Technology, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Tartu, Estonia 2Institute of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Tartu, Estonia *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Arak M., Soots K., Starast M., Olt J. (2018): Mechanical properties of blueberry stems. Res. Agr. Eng., 64: 202–208. In order to model and optimise the structural parameters of the working parts of agricultural machines, including har- vesting machines, the mechanical properties of the culture harvested must be known. The purpose of this article is to determine the mechanical properties of the blueberry plant’s stem; more precisely the tensile strength and consequent elastic modulus E. In order to achieve this goal, the measuring instrument Instron 5969L2610 was used and accompany- ing software BlueHill 3 was used for analysing the test results. The tested blueberry plant’s stems were collected from the blueberry plantation of the Farm Marjasoo. The diameters of the stems were measured, test units were prepared, tensile tests were performed, tensile strength was determined and the elastic modulus was obtained. Average value of the elastic modulus of the blueberry (Northblue) plant’s stem remained in the range of 1268.27–1297.73 MPa. Keywords: agricultural engineering; blueberry; harvesting; mechanical properties; elastic modulus Lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium abandoned peat fields because of soils with high Ait.) is a native naturally occurring plant in North organic matter content and low pH (Yakovlev et America. -

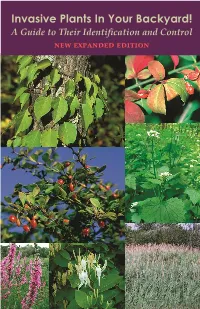

Invasive Plants in Your Backyard!

Invasive Plants In Your Backyard! A Guide to Their Identification and Control new expanded edition Do you know what plants are growing in your yard? Chances are very good that along with your favorite flowers and shrubs, there are non‐native invasives on your property. Non‐native invasives are aggressive exotic plants introduced intentionally for their ornamental value, or accidentally by hitchhiking with people or products. They thrive in our growing conditions, and with no natural enemies have nothing to check their rapid spread. The environmental costs of invasives are great – they crowd out native vegetation and reduce biological diversity, can change how entire ecosystems function, and pose a threat Invasive Morrow’s honeysuckle (S. Leicht, to endangered species. University of Connecticut, bugwood.org) Several organizations in Connecticut are hard at work preventing the spread of invasives, including the Invasive Plant Council, the Invasive Plant Working Group, and the Invasive Plant Atlas of New England. They maintain an official list of invasive and potentially invasive plants, promote invasives eradication, and have helped establish legislation restricting the sale of invasives. Should I be concerned about invasives on my property? Invasive plants can be a major nuisance right in your own backyard. They can kill your favorite trees, show up in your gardens, and overrun your lawn. And, because it can be costly to remove them, they can even lower the value of your property. What’s more, invasive plants can escape to nearby parks, open spaces and natural areas. What should I do if there are invasives on my property? If you find invasive plants on your property they should be removed before the infestation worsens. -

The Genomics of Wood Formation in Angiosperm Trees

The Genomics of Wood Formation in Angiosperm Trees Xinqiang He and Andrew T. Groover Abstract Advances in genomic science have enabled comparative approaches that can evaluate the evolution of genes and mechanisms underlying phenotypic traits relevant to angiosperm forest trees. Wood formation is an excellent subject for com- parative genomics, as it is an ancestral trait for angiosperms and has undergone significant modification in different angiosperm lineages. This chapter discusses some of the traits associated with wood formation, what is currently known about the genes and mechanisms regulating these traits, and how comparative evolution- ary genomic studies can be undertaken to provide more comprehensive views of the evolution and development of wood formation in angiosperms. Keywords Wood formation • Wood development • Wood evolution • Transcriptional regulation • Epigenetics • Comparative genomics Genomic Perspectives on the Evolutionary Origins and Variation in Angiosperm Wood Introduction The evolutionary and developmental biology of wood are fundamental to under- standing the amazing diversification of angiosperms. While flower morphology and reproductive characters associated with angiosperms have been the focus of numer- ous genetic and genomic evo-devo studies, wood development is a relatively neglected trait of angiosperm evolution and development that is now tractable for comparative and evolutionary genomic studies. The ability to produce wood from a X. He School of Life Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China A.T. Groover (*) Pacific Southwest Research Station, US Forest Service, Davis, 95618 CA, USA Department of Plant Biology, University of California Davis, Davis, 95618 CA, USA e-mail: [email protected] © Springer International Publishing AG 2017 205 A.T. Groover and Q.C.B. -

Tree Identification Guide

2048 OPAL guide to deciduous trees_Invertebrates 592 x 210 copy 17/04/2015 18:39 Page 1 Tree Rowan Elder Beech Whitebeam Cherry Willow Identification Guide Sorbus aucuparia Sambucus nigra Fagus sylvatica Sorbus aria Prunus species Salix species This guide can be used for the OPAL Tree Health Survey and OPAL Air Survey Oak Ash Quercus species Fraxinus excelsior Maple Hawthorn Hornbeam Crab apple Birch Poplar Acer species Crataegus monogyna Carpinus betulus Malus sylvatica Betula species Populus species Horse chestnut Sycamore Aesculus hippocastanum Acer pseudoplatanus London Plane Sweet chestnut Hazel Lime Elm Alder Platanus x acerifolia Castanea sativa Corylus avellana Tilia species Ulmus species Alnus species 2048 OPAL guide to deciduous trees_Invertebrates 592 x 210 copy 17/04/2015 18:39 Page 1 Tree Rowan Elder Beech Whitebeam Cherry Willow Identification Guide Sorbus aucuparia Sambucus nigra Fagus sylvatica Sorbus aria Prunus species Salix species This guide can be used for the OPAL Tree Health Survey and OPAL Air Survey Oak Ash Quercus species Fraxinus excelsior Maple Hawthorn Hornbeam Crab apple Birch Poplar Acer species Crataegus montana Carpinus betulus Malus sylvatica Betula species Populus species Horse chestnut Sycamore Aesculus hippocastanum Acer pseudoplatanus London Plane Sweet chestnut Hazel Lime Elm Alder Platanus x acerifolia Castanea sativa Corylus avellana Tilia species Ulmus species Alnus species 2048 OPAL guide to deciduous trees_Invertebrates 592 x 210 copy 17/04/2015 18:39 Page 2 ‹ ‹ Start here Is the leaf at least -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

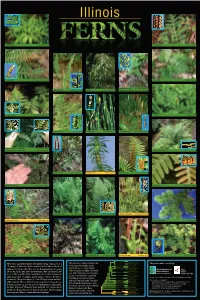

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants.