Synthetic Conversion of Leaf Chloroplasts Into Carotenoid-Rich Plastids Reveals Mechanistic Basis of Natural Chromoplast Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daylily Genetics Part 3 Variegated Or Broken Flower Colors: Jumping Genes?

~1~ Summer 11 DJ Science ‘Pink Stripes’ (Derrow, 2006) ‘Peppermint Ice’ (Lovell, 2004) — Photo courtesy of the hybridizer The unabridged version — Kyle Billadeau photo Daylily Genetics Part 3 Variegated or broken flower colors: Jumping genes? clonal and non-clonal patterns may be genet- some compound which affects pigmentation ic involving a change in DNA sequence or diffuses between cells By Maurice A. Dow, Ph.D. non-genetic. However, non-clonal patterns Region 4, Ontario, Canada are somewhat more likely to be environmen- Patterns help to identify possible causes Any characteristic can be variegated but tal or non-genetic. By looking at the patterns of pigmentation usually we think of variegated leaves or flow- Clonal sectors (see glossary) can provide in individual cells we can get general clues ers and of differences in color. However, var- some information about when during devel- about the causes of the variegation. For iegation can be present in both plants and opment the event occurred. Large sectors example a pattern on the upper epidermis of animals and in any tissue and affect any char- indicate the event occurred early during a variegated flower or leaf which is repeated acteristic. Variegation does not need to be development of the tissue or organ. Small and very similar to a pattern on its lower epi- obvious to the unaided human eye. It can be sectors indicate that the event occurred late dermis is unlikely to be genetic2. defined as any visible differences in the during development1. Few sectors indicate appearance or phenotype of the cells in a tis- that the event is infrequent or rare. -

The Biosynthesis of Carotenoids

THE BIOSYNTHESIS OF CAROTENOIDS C. 0. CHICHESTER Department of Food Science and Technology, University of a4fornia, Davis, Galjf 95616, U.S.A. INTRODUCTION Considerable progress has been made in the field of carotenoid bio- chemistry in the last ten to fifteen years. Prior to that very little, if anything, was known about the units which formed the intermediates of the coloured 40—carbon pigments, or the structures of those that were proposed as intermediates. Like all fields of biochemistry, as knowledge is accumulated specific problems are crystallized. These generally concern key areas, which until an understanding is achieved can substantially hinder the unification of a field or problem. The biochemistry of the carotenoids has arrived at this point. INTERMEDIATE COMPOUNDS IN CAROTENOID BIOSYNTHESIS There is general consensus as to the identity of the intermediate com- pounds which form the building blocks of the carotenoids. Studies in Phycornyces blakesleeanus, tomatoes, corn, carrots, Mucor hiemalis, spinach leaves, and bean leaves all coincide to indicate that the common building block of carotenoids is mevalonic acid'—7. Some experiments concerned with carotenoids, and many with sterols, have shown that /3-methyl-/3- hydroxyglutarate-CoA, and/or acetoacetic-CoA, are the normal sources of inevalonic acid" 8 In Phycomyces blalcesleeanus, as well as tomatoes, it has been shown rather unequivocally that the first steps in the conversion of meva- lonic acid to the C—40's are identical to those postulated for the formation of sterols911. The mevalonic acid is converted via the 5-phosphomevalonic acid to the 5-pyrophosphoryl mevalonic acid'2. This compound is then decarboxylated to form the z3-isopentenol pyrophosphate. -

Research Advances on Leaf and Wood Anatomy of Woody Species

rch: O ea pe es n A R t c s c Rodriguez et al., Forest Res 2016, 5:3 e e r s o s Forest Research F DOI: 10.4172/2168-9776.1000183 Open Access ISSN: 2168-9776 Research Article Open Access Research Advances on Leaf and Wood Anatomy of Woody Species of a Tamaulipan Thorn Scrub Forest and its Significance in Taxonomy and Drought Resistance Rodriguez HG1*, Maiti R1 and Kumari A2 1Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Carr. Nac. No. 85 Km. 45, Linares, Nuevo León 67700, México 2Plant Physiology, Agricultural College, Professor Jaya Shankar Telangana State Agricultural University, Polasa, Jagtial, Karimnagar, Telangana, India Abstract The present paper make a synthesis of a comparative leaf anatomy including leaf surface, leaf lamina, petiole and venation as well as wood anatomy of 30 woody species of a Tamaulipan Thorn Scrub, Northeastern Mexico. The results showed a large variability in anatomical traits of both leaf and wood anatomy. The variations of these anatomical traits could be effectively used in taxonomic delimitation of the species and adaptation of the species to xeric environments. For example the absence or low frequency of stomata on leaf surface, the presence of long palisade cells, and presence of narrow xylem vessels in the wood could be related to adaptation of the species to drought. Besides the species with dense venation and petiole with thick collenchyma and sclerenchyma and large vascular bundle could be well adapted to xeric environments. It is suggested that a comprehensive consideration of leaf anatomy (leaf surface, lamina, petiole and venation) and wood anatomy should be used as a basis of taxonomy and drought resistance. -

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

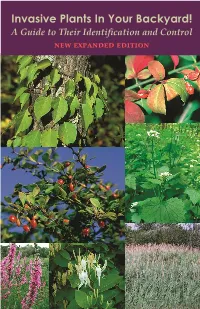

Invasive Plants in Your Backyard!

Invasive Plants In Your Backyard! A Guide to Their Identification and Control new expanded edition Do you know what plants are growing in your yard? Chances are very good that along with your favorite flowers and shrubs, there are non‐native invasives on your property. Non‐native invasives are aggressive exotic plants introduced intentionally for their ornamental value, or accidentally by hitchhiking with people or products. They thrive in our growing conditions, and with no natural enemies have nothing to check their rapid spread. The environmental costs of invasives are great – they crowd out native vegetation and reduce biological diversity, can change how entire ecosystems function, and pose a threat Invasive Morrow’s honeysuckle (S. Leicht, to endangered species. University of Connecticut, bugwood.org) Several organizations in Connecticut are hard at work preventing the spread of invasives, including the Invasive Plant Council, the Invasive Plant Working Group, and the Invasive Plant Atlas of New England. They maintain an official list of invasive and potentially invasive plants, promote invasives eradication, and have helped establish legislation restricting the sale of invasives. Should I be concerned about invasives on my property? Invasive plants can be a major nuisance right in your own backyard. They can kill your favorite trees, show up in your gardens, and overrun your lawn. And, because it can be costly to remove them, they can even lower the value of your property. What’s more, invasive plants can escape to nearby parks, open spaces and natural areas. What should I do if there are invasives on my property? If you find invasive plants on your property they should be removed before the infestation worsens. -

Genetic Modification of Tomato with the Tobacco Lycopene Β-Cyclase Gene Produces High Β-Carotene and Lycopene Fruit

Z. Naturforsch. 2016; 71(9-10)c: 295–301 Louise Ralley, Wolfgang Schucha, Paul D. Fraser and Peter M. Bramley* Genetic modification of tomato with the tobacco lycopene β-cyclase gene produces high β-carotene and lycopene fruit DOI 10.1515/znc-2016-0102 and alleviation of vitamin A deficiency by β-carotene, Received May 18, 2016; revised July 4, 2016; accepted July 6, 2016 which is pro-vitamin A [4]. Deficiency of vitamin A causes xerophthalmia, blindness and premature death, espe- Abstract: Transgenic Solanum lycopersicum plants cially in children aged 1–4 [5]. Since humans cannot expressing an additional copy of the lycopene β-cyclase synthesise carotenoids de novo, these health-promoting gene (LCYB) from Nicotiana tabacum, under the control compounds must be taken in sufficient quantities in the of the Arabidopsis polyubiquitin promoter (UBQ3), have diet. Consequently, increasing their levels in fruit and been generated. Expression of LCYB was increased some vegetables is beneficial to health. Tomato products are 10-fold in ripening fruit compared to vegetative tissues. the most common source of dietary lycopene. Although The ripe fruit showed an orange pigmentation, due to ripe tomato fruit contains β-carotene, the amount is rela- increased levels (up to 5-fold) of β-carotene, with negli- tively low [1]. Therefore, approaches to elevate β-carotene gible changes to other carotenoids, including lycopene. levels, with no reduction in lycopene, are a goal of Phenotypic changes in carotenoids were found in vegeta- plant breeders. One strategy that has been employed to tive tissues, but levels of biosynthetically related isopre- increase levels of health promoting carotenoids in fruits noids such as tocopherols, ubiquinone and plastoquinone and vegetables for human and animal consumption is were barely altered. -

Identification and Isolation of Genetic Elements Conferring Increased

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Intercollege Graduate Degree Program in Plant Physiology IDENTIFICATION AND ISOLATION OF GENETIC ELEMENTS CONFERRING INCREASED TOMATO FRUIT LYCOPENE CONTENT A Dissertation in Plant Physiology by Matthew Kinkade © 2010 Matthew Kinkade Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 The dissertation of Matthew Kinkade was reviewed and approved* by the following: Majid R. Foolad Professor of Plant Genetics Dissertation Advisor and Chair of Committee David M. Braun Associate Professor of Biological Sciences University of Missouri-Columbia John E. Carlson Professor of Molecular Genetics David R. Huff Associate Professor of Turfgrass Breeding and Genetics Yinong Yang Associate Professor of Plant Pathology Teh-hui Kao Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Program Chair, Intercollege Graduate Degree Program in Plant Biology *Signatures on file at the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT The cultivated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) is a vegetable crop produced and consumed around the world, and is a model system for the study of carotenoid accumulation. The dominant carotenoid in tomato is trans-lycopene, a powerful antioxidant that has been postulated to confer health benefits to humans and is responsible for the red appearance of ripe tomato fruits. Increasing lycopene content in tomato fruits represents an opportunity to increase market value for tomato crops, elevate the nutritional content of tomato for consumers, and to increase scientific understanding of carotenogenesis in plants. However, very few tomato alleles that cause increased lycopene accumulation in ripe fruits and are immediately useful for breeding purposes have been described in the literature. Given that little genetic variation exists within the cultivated tomato germplasm, wild Solanum species provide a unique opportunity to transfer new alleles into the cultigen. -

The Structure and Function of Grana-Free Thylakoid Membranes in Gerontoplasts of Senescent Leaves of Vicia Faba L

The Structure and Function of Grana-Free Thylakoid Membranes in Gerontoplasts of Senescent Leaves of Vicia faba L. H. Oskar Schmidt Zentralinstitut für Genetik und Kulturpflanzenforschung der AdW der DDR, 4325 Gatersleben Z. Naturforsch. 43c, 149-154 (1988); received March 11/September 7, 1987 Senescence, Chloroplast, Gerontoplast, Thylakoid Membrane Proteins, Electronmicroscopy, Photosynthesis In the course of yellowing (senescence) the leaves of Vicia faba L. lose 95% of their chlorophyll. Gerontoplasts develop from chloroplasts and aggregate with the pycnotic mitochon- dria and the cell nucleus in the senescent cells (organelle aggregation). The gerontoplasts contain only a few, unstacked thylakoid membranes but a large number of carotinoid-containing plasto- globuli, which after the degration of chlorophyll presumably assume the light protection of the cells. The thylakoid membranes of the gerontoplasts were isolated by means of a flotation method. Their polypeptide composition is characterized by a high proportion of light-harvesting complex. Evidence of relatively high photochemical activity shows that functional thylakoid mem- branes are present in the premortal senescence state of leaves and this suggests that there is functional compartmentation of the hydrolytic processes in this stage of the leaves' development. Introduction sequently degradation of the thylakoid membranes During the senescence (yellowing) of leaves, and of chlorophyll commences. Lipids and Caroti- genetically programmed hydrolytic processes reg- noids released in the process collect, at least to some ulated by hormones take place. These lead to the extent, in globulare osmiophilic droplets designated degradation of the cell organelles and chloroplasts as plastoglobuli according to Lichtenthaler and Sprey and finally to lysis of the cells [1,2]. -

Novel Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase Catalyzes the First Dedicated Step in Saffron Crocin Biosynthesis

Novel carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase catalyzes the first dedicated step in saffron crocin biosynthesis Sarah Frusciantea,b, Gianfranco Direttoa, Mark Brunoc, Paola Ferrantea, Marco Pietrellaa, Alfonso Prado-Cabrerod, Angela Rubio-Moragae, Peter Beyerc, Lourdes Gomez-Gomeze, Salim Al-Babilic,d, and Giovanni Giulianoa,1 aItalian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy, and Sustainable Development, Casaccia Research Centre, 00123 Rome, Italy; bSapienza, University of Rome, 00185 Rome, Italy; cFaculty of Biology, University of Freiburg, D-79104 Freiburg, Germany; dCenter for Desert Agriculture, Division of Biological and Environmental Science and Engineering, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Thuwal 23955-6900, Saudi Arabia; and eInstituto Botánico, Facultad de Farmacia, Universidad de Castilla–La Mancha, 02071 Albacete, Spain Edited by Rodney B. Croteau, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, and approved July 3, 2014 (received for review March 16, 2014) Crocus sativus stigmas are the source of the saffron spice and responsible for the synthesis of crocins have been characterized accumulate the apocarotenoids crocetin, crocins, picrocrocin, and in saffron and in Gardenia (5, 6). safranal, responsible for its color, taste, and aroma. Through deep Plant CCDs can be classified in five subfamilies according to transcriptome sequencing, we identified a novel dioxygenase, ca- the cleavage position and/or their substrate preference: CCD1, rotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 2 (CCD2), expressed early during CCD4, CCD7, CCD8, and nine-cis-epoxy-carotenoid dioxygen- stigma development and closely related to, but distinct from, the ases (NCEDs) (7–9). NCEDs solely cleave the 11,12 double CCD1 dioxygenase family. CCD2 is the only identified member of bond of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoids to produce the ABA precursor a novel CCD clade, presents the structural features of a bona fide xanthoxin. -

Direct Regulation of Phytoene Synthase Gene Expression and Carotenoid Biosynthesis by Phytochrome-Interacting Factors

Direct regulation of phytoene synthase gene expression and carotenoid biosynthesis by phytochrome-interacting factors Gabriela Toledo-Ortiza, Enamul Huqb, and Manuel Rodríguez-Concepcióna,1 aCentre for Research in Agricultural Genomics, CSIC-IRTA-UAB, 08034 Barcelona, Spain; and bSection of Molecular Cell and Developmental Biology and Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712 Edited* by Peter H. Quail, University of California, Albany, CA, and approved May 14, 2010 (received for review December 15, 2009) Carotenoids are key for plants to optimize carbon fixing using the known about the specific factors involved in this coordinated energy of sunlight. They contribute to light harvesting but also control, however. channel energy away from chlorophylls to protect the photosyn- Although the main pathway for carotenoid biosynthesis in plants thetic apparatus from excess light. Phytochrome-mediated light has been elucidated (9, 10), we still lack fundamental knowledge of signals are major cues regulating carotenoid biosynthesis in plants, the regulation of carotenogenesis in plant cells (11). In fact, to date but we still lack fundamental knowledge on the components of this no regulatory genes directly controlling carotenoid biosynthetic signaling pathway. Here we show that phytochrome-interacting gene expression have been isolated. Nonetheless, it is known that factor 1 (PIF1) and other transcription factors of the phytochrome- a major driving force for carotenoid production in different plant interacting factor (PIF) family down-regulate the accumulation of species is the transcriptional regulation of genes encoding phy- carotenoids by specifically repressing the gene encoding phytoene toene synthase (PSY), the first and main rate-determining enzyme synthase (PSY), the main rate-determining enzyme of the pathway. -

Tree Identification Guide

2048 OPAL guide to deciduous trees_Invertebrates 592 x 210 copy 17/04/2015 18:39 Page 1 Tree Rowan Elder Beech Whitebeam Cherry Willow Identification Guide Sorbus aucuparia Sambucus nigra Fagus sylvatica Sorbus aria Prunus species Salix species This guide can be used for the OPAL Tree Health Survey and OPAL Air Survey Oak Ash Quercus species Fraxinus excelsior Maple Hawthorn Hornbeam Crab apple Birch Poplar Acer species Crataegus monogyna Carpinus betulus Malus sylvatica Betula species Populus species Horse chestnut Sycamore Aesculus hippocastanum Acer pseudoplatanus London Plane Sweet chestnut Hazel Lime Elm Alder Platanus x acerifolia Castanea sativa Corylus avellana Tilia species Ulmus species Alnus species 2048 OPAL guide to deciduous trees_Invertebrates 592 x 210 copy 17/04/2015 18:39 Page 1 Tree Rowan Elder Beech Whitebeam Cherry Willow Identification Guide Sorbus aucuparia Sambucus nigra Fagus sylvatica Sorbus aria Prunus species Salix species This guide can be used for the OPAL Tree Health Survey and OPAL Air Survey Oak Ash Quercus species Fraxinus excelsior Maple Hawthorn Hornbeam Crab apple Birch Poplar Acer species Crataegus montana Carpinus betulus Malus sylvatica Betula species Populus species Horse chestnut Sycamore Aesculus hippocastanum Acer pseudoplatanus London Plane Sweet chestnut Hazel Lime Elm Alder Platanus x acerifolia Castanea sativa Corylus avellana Tilia species Ulmus species Alnus species 2048 OPAL guide to deciduous trees_Invertebrates 592 x 210 copy 17/04/2015 18:39 Page 2 ‹ ‹ Start here Is the leaf at least -

Microscope Studies on the Morphogenesis of Plastids V

Bot. Mag. Tokyo 84: 123-136 (March 25, 1971) Electron Microscope Studies on the Morphogenesis of Plastids V. Concerning One-dimensional Metamorphosis of the Plastids in Cryptomeriac Leaves* by Susumu TOYAMA** and Kazuo FUNAZAKIS** Received November 25, 1970 Abstract To know about the mechanism of interconversion of plastids, electron micro- scopic observations were made on Cryptomeria leaves which aquire a reddish brown color in winter and recover their green color in coming spring to summer. In normal green leaves, two different kinds of plastids have been observed, viz, the chloroplasts having well organized grana structure in mesophyll cells and those completely lacking grana lamellae in bundle sheath cells. General feature of plastids in reddish brown leaves, may be summarized as follows : (1) The presence of red granules of rhodoxanthin (a carotenoid), and a well developed lamellar system involving grana- and intergrana-lamellae. (2) The plastoglobules, osmio- philic granules in plastids, increase in number and size as compared with the chloroplasts in normal green leaves. (3) Shrinkage which is one of the character- istic features of senescent plastids is not observed. (4) RNA content in plastid stroma is almost unchanged throughout an entire leaf stage ranging from normal green to subsequent regreening. Basic structure of the plastids in regreened leaves is quite similar to that in winter leaves, except for some increase of thylakoid membrane and decrease of osmiophilic granules. Accordingly, it is presumed that the plastids appearing in reddish brown leaves are not mere chro- moplasts but those having an incipient nature of the chloroplast, since real chromoplasts can not be converted into the chloroplasts.