Takashi Miike's Dead Or Alive Trilogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

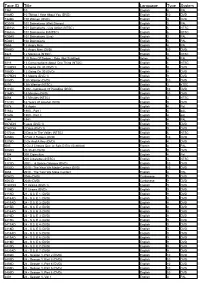

Title Call # Category

Title Call # Category 2LDK 42429 Thriller 30 seconds of sisterhood 42159 Documentary A 42455 Documentary A2 42620 Documentary Ai to kibo no machi = Town of love & hope 41124 Documentary Akage = Red lion 42424 Action Akahige = Red beard 34501 Drama Akai hashi no shita no nerui mizu = Warm water under bridge 36299 Comedy Akai tenshi = Red angel 45323 Drama Akarui mirai = Bright future 39767 Drama Akibiyori = Late autumn 47240 Akira 31919 Action Ako-Jo danzetsu = Swords of vengeance 42426 Adventure Akumu tantei = Nightmare detective 48023 Alive 46580 Action All about Lily Chou-Chou 39770 Always zoku san-chôme no yûhi 47161 Drama Anazahevun = Another heaven 37895 Crime Ankokugai no bijo = Underworld beauty 37011 Crime Antonio Gaudí 48050 Aragami = Raging god of battle 46563 Fantasy Arakimentari 42885 Documentary Astro boy (6 separate discs) 46711 Fantasy Atarashii kamisama 41105 Comedy Avatar, the last airbender = Jiang shi shen tong 45457 Adventure Bakuretsu toshi = Burst city 42646 Sci-fi Bakushū = Early summer 38189 Drama Bakuto gaijin butai = Sympathy for the underdog 39728 Crime Banshun = Late spring 43631 Drama Barefoot Gen = Hadashi no Gen 31326, 42410 Drama Batoru rowaiaru = Battle royale 39654, 43107 Action Battle of Okinawa 47785 War Bijitâ Q = Visitor Q 35443 Comedy Biruma no tategoto = Burmese harp 44665 War Blind beast 45334 Blind swordsman 44914 Documentary Blind woman's curse = Kaidan nobori ryu 46186 Blood : Last vampire 33560 Blood, Last vampire 33560 Animation Blue seed = Aokushimitama blue seed 41681-41684 Fantasy Blue submarine -

Masters Title Page

MULTICULTURALISM AND ALIENATION IN CONTEMPORARY JAPANESE SOCIETY AS SEEN IN THE FILMS OF TAKASHI MIIKE Steven A. Balsomico A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Ronald E. Shields, Advisor Walter Grunden ii ABSTRACT Ronald E. Shields, Advisor Through his films, Takashi Miike reminds audiences of the diverse populations within Japan. He criticizes elements of the Japanese sociological structures that alienate minorities and outcasts. Through the socialization process, Japanese youth learn the importance of “fitting in” and attending to the needs of the group. Clear distinctions of who are “inside” and “outside” are made early on and that which is “outside” is characterized as outcast and forbidden. In three of his films, "Blues Harp," "Dead or Alive," and "Deadly Outlaw: Rekka," Miike includes individuals who have been situated as outsiders. In "Blues Harp," Chuji, due to his obvious heritage, cannot find a place in society, and thus exists on the fringes. In "Dead or Alive," Ryuichi has felt that the country in which he lives has placed him in a disadvantaged status: therefore, he must strike out on his own, attempting to achieve happiness through criminal means. In "Deadly Outlaw: Rekka," Kunisada, an outsider by blood and incarceration, cannot relate to his peers in the world. As a result, he lashes out against the world in violence, becoming an individual who is portrayed as a wild beast. When these outsiders attempt to form their own groups, they often face eventual failure. -

Audition How Does the 1999 Film Relate to the Issues That Japanese Men and Women Face in Relation to Romantic Pairing?

University of Roskilde Audition How does the 1999 film relate to the issues that Japanese men and women face in relation to romantic pairing? Supervisor: Björn Hakon Lingner Group members: Student number: Anna Klis 62507 Avin Mesbah 61779 Dejan Omerbasic 55201 Mads F. B. Hansen 64518 In-depth project Characters: 148,702 Fall 2018 University of Roskilde Table of content Problem Area ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Problem Formulation .............................................................................................................................. 9 Motivation ............................................................................................................................................... 9 Delimitation ........................................................................................................................................... 10 Method .................................................................................................................................................. 11 Theory .................................................................................................................................................... 12 Literature review ............................................................................................................................... 12 Social Exchange Theory .................................................................................................................... -

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Japanese Cinema at the Digital Turn Laura Lee, Florida State University

1 Between Frames: Japanese Cinema at the Digital Turn Laura Lee, Florida State University Abstract: This article explores how the appearance of composite media arrangements and the prominence of the cinematic mechanism in Japanese film are connected to a nostalgic preoccupation with the materiality of the filmic image, and to a new critical function for film-based cinema in the digital age. Many popular Japanese films from the early 2000s layer perceptually distinct media forms within the image. Manipulation of the interval between film frames—for example with stop-motion, slow-motion and time-lapse techniques—often overlays the insisted-upon interval between separate media forms at these sites of media layering. Exploiting cinema’s temporal interval in this way not only foregrounds the filmic mechanism, but it in effect stages the cinematic apparatus, displaying it at a medial remove as a spectacular site of difference. In other words, cinema itself becomes refracted through these hybrid media combinations, which paradoxically facilitate a renewed encounter with cinema by reawakening a sensuous attachment to it at the very instant that it appears to be under threat. This particular response to developments in digital technologies suggests how we might more generally conceive of cinema finding itself anew in the contemporary media landscape. The advent of digital media and the perceived danger it has implied for the status of cinema have resulted in an inevitable nostalgia for the unique properties of the latter. In many Japanese films at the digital turn this manifests itself as a staging of the cinematic apparatus, in 1 which cinema is refracted through composite media arrangements. -

Filmography of Case Study Films (In Chronological Order of Release)

FILMOGRAPHY OF CASE STUDY FILMS (IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER OF RELEASE) Kairo / Pulse 118 mins, col. Released: 2001 (Japan) Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa Screenplay: Kiyoshi Kurosawa Cinematography: Junichiro Hayashi Editing: Junichi Kikuchi Sound: Makio Ika Original Music: Takefumi Haketa Producers: Ken Inoue, Seiji Okuda, Shun Shimizu, Atsuyuki Shimoda, Yasuyoshi Tokuma, and Hiroshi Yamamoto Main Cast: Haruhiko Kato, Kumiko Aso, Koyuki, Kurume Arisaka, Kenji Mizuhashi, and Masatoshi Matsuyo Production Companies: Daiei Eiga, Hakuhodo, Imagica, and Nippon Television Network Corporation (NTV) Doruzu / Dolls 114 mins, col. Released: 2002 (Japan) Director: Takeshi Kitano Screenplay: Takeshi Kitano Cinematography: Katsumi Yanagijima © The Author(s) 2016 217 A. Dorman, Paradoxical Japaneseness, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-55160-3 218 FILMOGRAPHY OF CASE STUDY FILMS… Editing: Takeshi Kitano Sound: Senji Horiuchi Original Music: Joe Hisaishi Producers: Masayuki Mori and Takio Yoshida Main Cast: Hidetoshi Nishijima, Miho Kanno, Tatsuya Mihashi, Chieko Matsubara, Tsutomu Takeshige, and Kyoko Fukuda Production Companies: Bandai Visual Company, Offi ce Kitano, Tokyo FM Broadcasting Company, and TV Tokyo Sukiyaki uesutan jango / Sukiyaki Western Django 121 mins, col. Released: 2007 (Japan) Director: Takashi Miike Screenplay: Takashi Miike and Masa Nakamura Cinematography: Toyomichi Kurita Editing: Yasushi Shimamura Sound: Jun Nakamura Original Music: Koji Endo Producers: Nobuyuki Tohya, Masao Owaki, and Toshiaki Nakazawa Main Cast: Hideaki Ito, Yusuke Iseya, Koichi Sato, Kaori Momoi, Teruyuki Kagawa, Yoshino Kimura, Masanobu Ando, Shun Oguri, and Quentin Tarantino Production Companies: A-Team, Dentsu, Geneon Entertainment, Nagoya Broadcasting Network (NBN), Sedic International, Shogakukan, Sony Pictures Entertainment (Japan), Sukiyaki Western Django Film Partners, Toei Company, Tokyu Recreation, and TV Asahi Okuribito / Departures 130 mins, col. -

Newsletter 09/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 09/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 206 - April 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 09/07 (Nr. 206) April 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, und Fach. Wie versprochen gibt es dar- diesem Editorial auch gar nicht weiter liebe Filmfreunde! in unsere Reportage vom Widescreen aufhalten. Viel Spaß und bis zum näch- Es hat mal wieder ein paar Tage länger Weekend in Bradford. Also Lesestoff sten Mal! gedauert, aber nun haben wir Ausgabe satt. Und damit Sie auch gleich damit 206 unseres Newsletters unter Dach beginnen können, wollen wir Sie mit Ihr LASER HOTLINE Team LASER HOTLINE Seite 2 Newsletter 09/07 (Nr. 206) April 2007 US-Debüt der umtriebigen Pang-Brüder, die alle Register ihres Könnens ziehen, um im Stil von „Amityville Horror“ ein mit einem Fluch belegtes Haus zu Leben zu erwecken. Inhalt Roy und Denise Solomon ziehen mit ihrer Teenager-Tochter Jess und ihrem kleinen Sohn Ben in ein entlegenes Farmhaus in einem Sonnenblumenfeld in North Dakota. Dass sich dort womöglich übernatürliche Dinge abspielen könnten, bleibt von den Erwachsenen unbemerkt. Aber Ben und kurz darauf Jess spüren bald, dass nicht alles mit rechten Dingen zugeht. Weil ihr die Eltern nicht glauben wollen, recherchiert Jess auf eigene Faust und erfährt, dass sich in ihrem neuen Zuhause sechs Jahre zuvor ein bestialischer Mord abgespielt hat. Kritik Für sein amerikanisches Debüt hat sich das umtriebige Brüderpaar Danny und Oxide Pang („The Eye“) eine Variante von „Amityville Horror“ ausgesucht, um eine amerikanische Durchschnittsfamilie nach allen Regeln der Kunst mit übernatürlichem Terror zu überziehen. -

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes K-19 : the widowmaker 45205 Kaajal 36701 Family/Musical Ka-annanā ʻishrūn mustaḥīl = Like 20 impossibles 41819 Ara Kaante 36702 Crime Hin Kabhi kabhie 33803 Drama/Musical Hin Kabhi khushi kabhie gham-- 36203 Drama/Musical Hin Kabot Thāo Sīsudāčhan = The king maker 43141 Kabul transit 47824 Documentary Kabuliwala 35724 Drama/Musical Hin Kadının adı yok 34302 Turk/VCD Kadosh =The sacred 30209 Heb Kaenmaŭl = Seaside village 37973 Kor Kagemusha = Shadow warrior 40289 Drama Jpn Kagerōza 42414 Fantasy Jpn Kaidan nobori ryu = Blind woman's curse 46186 Thriller Jpn Kaiju big battel 36973 Kairo = Pulse 42539 Horror Jpn Kaitei gunkan = Atragon 42425 Adventure Jpn Kākka... kākka... 37057 Tamil Kakushi ken oni no tsume = The hidden blade 43744 Romance Jpn Kakushi toride no san akunin = Hidden fortress 33161 Adventure Jpn Kal aaj aur kal 39597 Romance/Musical Hin Kal ho naa ho 41312, 42386 Romance Hin Kalyug 36119 Drama Hin Kama Sutra 45480 Kamata koshin-kyoku = Fall guy 39766 Comedy Jpn Kān Klūai 45239 Kantana Animation Thai Kanak Attack 41817 Drama Region 2 Kanal = Canal 36907, 40541 Pol Kandahar : Safar e Ghandehar 35473 Farsi Kangwŏn-do ŭi him = The power of Kangwon province 38158 Kor Kannathil muthamittal = Peck on the cheek 45098 Tamil Kansas City 46053 Kansas City confidential 36761 Kanto mushuku = Kanto warrior 36879 Crime Jpn Kanzo sensei = Dr. Akagi 35201 Comedy Jpn Kao = Face 41449 Drama Jpn Kaos 47213 Ita Kaosu = Chaos 36900 Mystery Jpn Karakkaze yarô = Afraid to die 45336 Crime Jpn Karakter = Character -

Divx Na Cd Strona 1

Divx na cd 0000 0000 Original title/Tytul oryginalny 0000 Polish CD//Subt/Nap title/Tytul polski isy 10ThingsIHateAboutYou(1999) Zakochana zlosnica 1/pl 1492: Conquest of Paradise (AKA 1492: Odkrycie raju / 1492: Christophe1492:Wyprawa Colomb do / raju1492: La conquête du paradis / 1492: La conquista del paraíso) (1992) 2 Fast 2 Furious (2003) Za szybcy za wsciekli 1/pl 2046(2004) 2046 . 2/pl 21Grams (2003) 21 Gram 2/pl 25th Hour(2002) 25 godzina 2/pl 3000Miles toGraceland(2001) 3000 mil do Graceland 1/pl 50FirstDates(2004) 50 pierwszych randek 1/pl 54(1998) Klub 54 AboutSchmidt(2002) About Schmidt 2/pl Abrelosojos(AKA Open Your Eyes) (1997) Otworz oczy 1/pl Adaptation (2002) Adaptacja 2/pl Alfie(2004) Alfie 2/pl Ali(2001) Ali Alien3 (1992) Obcy 3 AlienResurrection (1997) 4 Obcy 4 – Przebudzenie Obcy 2 – Decydujace Aliens (1986) 2 starcie Alienvs. Predator(AKA Alienversus Predator/ AvP) (2004) Obcy Kontra Predator Amelia/ Fabuleux destin d'Amélie Poulain, Le (AKA Amelie from AmeliaMontmartre / Amelie of Montmartre / Fabelhafte Welt der Amelie, Die / Fabulous Destiny of Amelie Poulain / Amelie) (2001) AmericanBeauty(1999) American Beauty AmericanPsycho(2000) American Psycho Anaconda(1997) Anakonda AngelHeart (1987) Harry Angel AngerManagement(2003) Dwoch gniewnych ludzi Animal Farm (1999) Folwark zwierzecy Animatrix, The(2003) Animatrix AntwoneFisher(2002) Antwone Fisher Apocalypse Now(AKA Apocalypse Now: Redux(2001)) (1979) DirApokalipsa cut Aragami(2003) Aragami Atame(AKA Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!) (1990) Zwiaz mnie Avalanche(AKA Nature -

Zeughauskino: Kinematografie Heute: Japan

KINEMATOGRAFIE HEUTE: JAPAN Seit Jahren eine der größten Filmproduktionen der Welt ist dem japanischen Kino eine einzigartige Vielfalt und Kraft eigen: ein Reichtum fiktionaler Formen, der aus der Geschichte des japani- schen Films wie auch aus den gesellschaftlichen Verwerfungen der Gegenwart schöpft; eine lebendige Dokumentarfilmkultur, die klas- sischen Anliegen und Arbeitsweisen folgen kann, die aber auch moderne und hybride Formen kennt, und schließlich natürlich ein Kino des animierten Films, das weltweit einzigartig ist. In mancher Hinsicht dem europäischen oder westlichen Kino ähnlich, hat das japanische Filmschaffen auch Filmsprachen und Bilderwelten her- vorgebracht, die hierzulande nicht entstehen: Die Vorführung eines japanischen Films kann zu einem atemberaubenden Erlebnis werden. Die Filmreihe KINEMATOGRAFIE HEUTE: JAPAN, die das zeitgenössi- sche japanische Kino der letzten vier Jahre vorstellt, ermöglicht eine Vielzahl dieser Erlebnisse. Eine Filmreihe anlässlich des Jubiläums »150 Jahre Japan – Deutsch- land«, mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Botschaft von Japan. Kūki Ningyō Air Doll J 2009, R: Hirokazu Koreeda, D: Doona Bae, Arata, Itsuji Itao, Jō Odagiri, 125’ | 35 mm, OmeU Das Kino kann beschrieben werden als eine Apparatur, die tote, erstarrte Bilder durch Bewegung dynamisiert und zum Leben erweckt. Vielleicht sind auch deshalb Erzählungen über künstliches Leben seit jeher ein privilegier- tes Sujet des Mediums. Hirokazu Koreeda schließt an diese Tradition an, bedient sich insbesondere bei Ernst Lubitschs Stummfilmklassiker Die Pup- pe und fügt ihr eine eigenwillige Variante hinzu: Zum Leben erweckt wird hier eine Sexpuppe. Koreeda nimmt diese absurde Prämisse wortwörtlich, ohne dass Air Doll deswegen zum Exploitationfilm werden würde. Statt des- sen erzählt der Film die Subjektkonstitution eines sich seiner eigenen Funk- tion bewussten Sexspielzeugs als modernes Märchen. -

JAPAN CUTS: Festival of New Japanese Film Announces Full Slate of NY Premieres

Media Contacts: Emma Myers, [email protected], 917-499-3339 Shannon Jowett, [email protected], 212-715-1205 Asako Sugiyama, [email protected], 212-715-1249 JAPAN CUTS: Festival of New Japanese Film Announces Full Slate of NY Premieres Dynamic 10th Edition Bursting with Nearly 30 Features, Over 20 Shorts, Special Sections, Industry Panel and Unprecedented Number of Special Guests July 14-24, 2016, at Japan Society "No other film showcase on Earth can compete with its culture-specific authority—or the quality of its titles." –Time Out New York “[A] cinematic cornucopia.” "Interest clearly lies with the idiosyncratic, the eccentric, the experimental and the weird, a taste that Japan rewards as richly as any country, even the United States." –The New York Times “JAPAN CUTS stands apart from film festivals that pander to contemporary trends, encouraging attendees to revisit the past through an eclectic slate of both new and repertory titles.” –The Village Voice New York, NY — JAPAN CUTS, North America’s largest festival of new Japanese film, returns for its 10th anniversary edition July 14-24, offering eleven days of impossible-to- see-anywhere-else screenings of the best new movies made in and around Japan, with special guest filmmakers and stars, post-screening Q&As, parties, giveaways and much more. This year’s expansive and eclectic slate of never before seen in NYC titles boasts 29 features (1 World Premiere, 1 International, 14 North American, 2 U.S., 6 New York, 1 NYC, and 1 Special Sneak Preview), 21 shorts (4 International Premieres, 9 North American, 1 U.S., 1 East Coast, 6 New York, plus a World Premiere of approximately 12 works produced in our Animation Film Workshop), and over 20 special guests—the most in the festival’s history. -

Newsletter 19/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 19/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 190 - September 2006 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 19/06 (Nr. 190) September 2006 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, sein, mit der man alle Fans, die bereits ein lich zum 22. Bond-Film wird es bestimmt liebe Filmfreunde! Vorgängermodell teuer erworben haben, wieder ein nettes Köfferchen geben. Dann Was gibt es Neues aus Deutschland, den ärgern wird. Schick verpackt in einem ed- möglicherweise ja schon in komplett hoch- USA und Japan in Sachen DVD? Der vor- len Aktenkoffer präsentiert man alle 20 auflösender Form. Zur Stunde steht für den liegende Newsletter verrät es Ihnen. Wie offiziellen Bond-Abenteuer als jeweils 2- am 13. November 2006 in den Handel ge- versprochen haben wir in der neuen Ausga- DVD-Set mit bild- und tonmäßig komplett langenden Aktenkoffer noch kein Preis be wieder alle drei Länder untergebracht. restaurierten Fassungen. In der entspre- fest. Wer sich einen solchen sichern möch- Mit dem Nachteil, dass wieder einmal für chenden Presseerklärung heisst es dazu: te, der sollte aber nicht zögern und sein Grafiken kaum Platz ist. Dieses Mal ”Zweieinhalb Jahre arbeitete das MGM- Exemplar am besten noch heute vorbestel- mussten wir sogar auf Cover-Abbildungen Team unter Leitung von Filmrestaurateur len. Und wer nur an einzelnen Titeln inter- in der BRD-Sparte verzichten. Der John Lowry und anderen Visionären von essiert ist, den wird es freuen, dass es die Newsletter mag dadurch vielleicht etwas DTS Digital Images, dem Marktführer der Bond-Filme nicht nur als Komplettpaket ”trocken” wirken, bietet aber trotzdem den digitalen Filmrestauration, an der komplet- geben wird, sondern auch gleichzeitig als von unseren Lesern geschätzten ten Bildrestauration und peppte zudem alle einzeln erhältliche 2-DVD-Sets.