Masters Title Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWS RELEASE for Immediate Release Ministry of Tourism, Sport and the Arts 2006TSA0018-000597 May 16, 2006

NEWS RELEASE For Immediate Release Ministry of Tourism, Sport and the Arts 2006TSA0018-000597 May 16, 2006 TV PRODUCTIONS DOUBLE OVER LAST MAY VANCOUVER – The number of television productions currently underway in B.C. is double that of last year, Tourism, Sport and the Arts Minister Olga Ilich announced today. Currently, there are 13 series and five movies-of-the-week in production. In May 2005, six series, one mini-series, one pilot and one movie-of-the-week were in production. “Globally, we are seeing an increased interest in dramatic television series – and today’s numbers give us reason to be optimistic that 2006 will be a strong year for us as well,” said Ilich. “This is testament to our skilled crews, world-class facilities and innovative measures taken by government and industry to ensure B.C. remains competitive.” “Our creative economy is only as strong as the talent pool within it,” said Ilich. “The film and television industry is a very fluid sector and B.C.’s creative pool is experienced and nimble enough to adjust to new conditions and seize new opportunities.” B.C.’s film and television industry experienced a major turnaround in 2005, reaching $1.233 billion, up from $801 million in 2004. Television production in 2005 included 31 television series, 37 movies-of-the-week, 15 television pilots and five mini-series. Television series currently shooting in B.C. include: Stargate SG-1, Battlestar Galactica, The 440, Masters of Horror and Robson Arms. New series this year include: Blade, Eureka, Kyle XY, Psych, Saved and Three Moons Over Milford. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Kinotayo-2010

PROGRAMME - PROGRAMME - PROGRAMME - PROGRAMME - 20 Nov 11 Déc 2010 5eme FESTIVAL DU FILM JAPONAIS CONTEMPORAIN Mascotte de Kinotayo 2010 140 projectionsAvec la participation d'Écrans - d'asie 25 villes Kinotayo2010 Yoshi OIDA, l’Acteur flottant, président du Festival Kinotayo 2010 Pour le festival Kinotayo, c’est un immense honneur que d’avoir pour président ce comédien, acteur, metteur en scène et écrivain insaisissable, animé par l’omniprésente énergie de la vie, sur scène et en dehors. Yoshi Oida est un acteur hors du commun. Né à Kobe en 1933, il a dédié sa vie aux théâtres du monde entier, en ayant pour seule ligne de conduite de renoncer à la facilité. Son apprentissage commence au Japon : il est initié au théâtre Nô par les plus grands maîtres de l’école Okura. De cette expérience, il retirera l’importance de l’harmonie entre tous les éléments qui constituent l’outil principal du comédien : son corps. Puis en 1968 Yoshi Oida est invité à Paris par Jean-Louis Barrault pour travailler avec Peter Brook. Il fonde avec ce dernier le Centre International de Recherche Théâtrale (CIRT). Au contact du « magicien du théâtre européen », il apprend que le comédien doit être « un vent léger, qui devenant de plus en plus fort, doit allumer une flamme et la faire grandir ». Aux côtés du maître, il apprend également la mise en scène, métier qui l’occupe énormément aujourd’hui. Il sillonne alors le monde à la recherche de la maîtrise théâtrale la plus complète, apprenant les jeux Africains, Indien, Persan. Il s’interroge sur la frontière entre la scène et la vie de tous les jours : « Qu’ai-je appris sur la scène qui pourrait m’aider à vivre ma vie d’homme ordinaire ? ». -

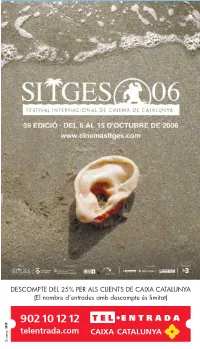

¥PDF Programa De Ma 06.Fh9

Disseny: IMF DESCOMPTE DEL25%PERALS CLIENTSDECAIXACATALUNYA (El nombred’entradesambdescompte éslimitat) PROGRAMACIÓ * Les sessions que porten un asterisc compten amb la presència de part de l’equip artístic i/o tècnic. DIVENDRES 6 9.15h. Casino Prado. The Last Circus (curt) + Blood Tea and Red Strings (Anima’t) 11h. Casino Prado. Black Moon (Europa Imaginària) 11.15h. El Retiro. Seance (Orient Express – Casa Asia) 13h. El Retiro. Eye of the Spider (Orient Express – Kurosawa) 13.15h. Casino Prado. La Sabina (Europa Imaginària) 13.45h. Auditori. Ils (Secció Oficial Fantàstic) 15h. El Retiro. Taxidermia (Secció Oficial Fantàstic) 15h. Casino Prado. Ulisse (Europa Imaginària) 15.15h. Auditori. Broken (S.O.Méliès) 17h. El Retiro. Duelist (Orient Express – Casa Asia) * 17h. Casino Prado. Blue Velvet (Sitges Clàssics – Lynch) 18h. Auditori. Gala Inauguració Sitges 2006: For(r)est in the Des(s)ert (curt) + El Laberinto del Fauno * 19.15h. El Retiro. La Hora Fría (Secció Oficial Fantàstic) 19.15h. Casino Prado. Fantastic Voyage (Sitges Clàssics - Fleischer) 20.50h. Auditori. El Laberinto del Fauno (Passi privat Tel-Entrada Caixa Catalunya) 21.15h. El Retiro. Avida (S.O. Noves Visions) 21.15h. Casino Prado. The Last Circus (curt) + Blood Tea and Red Strings (Anima’t) 23h. Auditori. Ils (Secció Oficial Fantàstic) * 23h. El Retiro. The Pulse (Secció Oficial Première) 23h. Casino Prado. Soylent Green (Sitges Clàssics - Fleischer) 00.45h. Auditori. Broken (S.O. Méliès) 1h. El Retiro. Masters of Horror (I) (Midnight X-Treme) 1h. Casino Prado. Mondo Macabro (I): The Warrior + Devil’s Sword (Midnight X-Treme) DISSABTE 7 9h. El Retiro. Edmond (S.O. -

Title Call # Category

Title Call # Category 2LDK 42429 Thriller 30 seconds of sisterhood 42159 Documentary A 42455 Documentary A2 42620 Documentary Ai to kibo no machi = Town of love & hope 41124 Documentary Akage = Red lion 42424 Action Akahige = Red beard 34501 Drama Akai hashi no shita no nerui mizu = Warm water under bridge 36299 Comedy Akai tenshi = Red angel 45323 Drama Akarui mirai = Bright future 39767 Drama Akibiyori = Late autumn 47240 Akira 31919 Action Ako-Jo danzetsu = Swords of vengeance 42426 Adventure Akumu tantei = Nightmare detective 48023 Alive 46580 Action All about Lily Chou-Chou 39770 Always zoku san-chôme no yûhi 47161 Drama Anazahevun = Another heaven 37895 Crime Ankokugai no bijo = Underworld beauty 37011 Crime Antonio Gaudí 48050 Aragami = Raging god of battle 46563 Fantasy Arakimentari 42885 Documentary Astro boy (6 separate discs) 46711 Fantasy Atarashii kamisama 41105 Comedy Avatar, the last airbender = Jiang shi shen tong 45457 Adventure Bakuretsu toshi = Burst city 42646 Sci-fi Bakushū = Early summer 38189 Drama Bakuto gaijin butai = Sympathy for the underdog 39728 Crime Banshun = Late spring 43631 Drama Barefoot Gen = Hadashi no Gen 31326, 42410 Drama Batoru rowaiaru = Battle royale 39654, 43107 Action Battle of Okinawa 47785 War Bijitâ Q = Visitor Q 35443 Comedy Biruma no tategoto = Burmese harp 44665 War Blind beast 45334 Blind swordsman 44914 Documentary Blind woman's curse = Kaidan nobori ryu 46186 Blood : Last vampire 33560 Blood, Last vampire 33560 Animation Blue seed = Aokushimitama blue seed 41681-41684 Fantasy Blue submarine -

Film Reviews

Page 117 FILM REVIEWS Year of the Remake: The Omen 666 and The Wicker Man Jenny McDonnell The current trend for remakes of 1970s horror movies continued throughout 2006, with the release on 6 June of John Moore’s The Omen 666 (a sceneforscene reconstruction of Richard Donner’s 1976 The Omen) and the release on 1 September of Neil LaBute’s The Wicker Man (a reimagining of Robin Hardy’s 1973 film of the same name). In addition, audiences were treated to remakes of The Hills Have Eyes, Black Christmas (due Christmas 2006) and When a Stranger Calls (a film that had previously been ‘remade’ as the opening sequence of Scream). Finally, there was Pulse, a remake of the Japanese film Kairo, and another addition to the body of remakes of nonEnglish language horror films such as The Ring, The Grudge and Dark Water. Unsurprisingly, this slew of remakes has raised eyebrows and questions alike about Hollywood’s apparent inability to produce innovative material. As the remakes have mounted in recent years, from Planet of the Apes to King Kong, the cries have grown ever louder: Hollywood, it would appear, has run out of fresh ideas and has contributed to its evergrowing bank balance by quarrying the classics. Amid these accusations of Hollywood’s imaginative and moral bankruptcy to commercial ends in tampering with the films on which generations of cinephiles have been reared, it can prove difficult to keep a level head when viewing films like The Omen 666 and The Wicker Man. -

Synopsis Cast & Crew

SYNOPSIS CAST & CREW Yuko is back in Japan after being freed as a hostage in the Middle Yuko: Fusako URABE written & directed by Masahiro KOBAYASHI East. her father: Ryuzo TANAKA music: Hiroshi HAYASHI But six months after, her return is proving to be much more of her lover: Takayuki KATO cinematography: Koichi SAITOH an ordeal. It seems the whole of Japanese society is against her the father’s boss: Kikujiro HONDA first assistant director/production manager: Junya KAWASE Monkey Town Productions present after being embarrassed and horrified at the international attention the hotel owner: Teruyuki KAGAWA first assistant camera: Sachi KAGAMI she received. Yuko is «bashed» every day by insults in the street, the stepmother: Nene OTSUKA lighting: Yasushi HANAMURA anonymous phone calls and even physical violence. sound design: Tatsuo YOKOYAMA Fired from her job, her isolation from the outside world deepens editor: Naoki KANEKO along with her despair. location superviser: Yukari HATANO After losing her only supporter – her father - she begins to think the producers: Masahiro KOBAYASHI & Naoko OKAMURA unthinkable: to return to the only place where the expressions on people’s faces aren’t cold or filled with anger, to the only place she BASHING has ever felt needed. While buying Japanese sweets for the Middle Eastern children she allows herself a secret little smile. Masahiro Kobayashi world sales: CELLULOID DREAMS distributrion france: OCEAN IN PARIS IN PARIS 2 Rue Turgot, 75009 Paris, France 40 avenue Marceau, 75008 Paris, France Yuko rentre au Japon après s’être fait prendre en otage au Moyen- T: +33 1 49 70 03 70 T: +33 1 56 62 30 30 Orient. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Audition How Does the 1999 Film Relate to the Issues That Japanese Men and Women Face in Relation to Romantic Pairing?

University of Roskilde Audition How does the 1999 film relate to the issues that Japanese men and women face in relation to romantic pairing? Supervisor: Björn Hakon Lingner Group members: Student number: Anna Klis 62507 Avin Mesbah 61779 Dejan Omerbasic 55201 Mads F. B. Hansen 64518 In-depth project Characters: 148,702 Fall 2018 University of Roskilde Table of content Problem Area ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Problem Formulation .............................................................................................................................. 9 Motivation ............................................................................................................................................... 9 Delimitation ........................................................................................................................................... 10 Method .................................................................................................................................................. 11 Theory .................................................................................................................................................... 12 Literature review ............................................................................................................................... 12 Social Exchange Theory .................................................................................................................... -

Filmography of Case Study Films (In Chronological Order of Release)

FILMOGRAPHY OF CASE STUDY FILMS (IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER OF RELEASE) Kairo / Pulse 118 mins, col. Released: 2001 (Japan) Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa Screenplay: Kiyoshi Kurosawa Cinematography: Junichiro Hayashi Editing: Junichi Kikuchi Sound: Makio Ika Original Music: Takefumi Haketa Producers: Ken Inoue, Seiji Okuda, Shun Shimizu, Atsuyuki Shimoda, Yasuyoshi Tokuma, and Hiroshi Yamamoto Main Cast: Haruhiko Kato, Kumiko Aso, Koyuki, Kurume Arisaka, Kenji Mizuhashi, and Masatoshi Matsuyo Production Companies: Daiei Eiga, Hakuhodo, Imagica, and Nippon Television Network Corporation (NTV) Doruzu / Dolls 114 mins, col. Released: 2002 (Japan) Director: Takeshi Kitano Screenplay: Takeshi Kitano Cinematography: Katsumi Yanagijima © The Author(s) 2016 217 A. Dorman, Paradoxical Japaneseness, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-55160-3 218 FILMOGRAPHY OF CASE STUDY FILMS… Editing: Takeshi Kitano Sound: Senji Horiuchi Original Music: Joe Hisaishi Producers: Masayuki Mori and Takio Yoshida Main Cast: Hidetoshi Nishijima, Miho Kanno, Tatsuya Mihashi, Chieko Matsubara, Tsutomu Takeshige, and Kyoko Fukuda Production Companies: Bandai Visual Company, Offi ce Kitano, Tokyo FM Broadcasting Company, and TV Tokyo Sukiyaki uesutan jango / Sukiyaki Western Django 121 mins, col. Released: 2007 (Japan) Director: Takashi Miike Screenplay: Takashi Miike and Masa Nakamura Cinematography: Toyomichi Kurita Editing: Yasushi Shimamura Sound: Jun Nakamura Original Music: Koji Endo Producers: Nobuyuki Tohya, Masao Owaki, and Toshiaki Nakazawa Main Cast: Hideaki Ito, Yusuke Iseya, Koichi Sato, Kaori Momoi, Teruyuki Kagawa, Yoshino Kimura, Masanobu Ando, Shun Oguri, and Quentin Tarantino Production Companies: A-Team, Dentsu, Geneon Entertainment, Nagoya Broadcasting Network (NBN), Sedic International, Shogakukan, Sony Pictures Entertainment (Japan), Sukiyaki Western Django Film Partners, Toei Company, Tokyu Recreation, and TV Asahi Okuribito / Departures 130 mins, col. -

Marie-José Nat JFM2020:Mise En Page 1 19/12/19 18:19 Page 2

JFM2020:Mise en page 1 19/12/19 18:19 Page 1 Cinémathèque de Corse Janvier Février Mars 2020 Stan & Ollie • Jon S. Baird Marie-José Nat JFM2020:Mise en page 1 19/12/19 18:19 Page 2 Sommaire Hommage à Marie-José Nat.............................................................................................................................2 Les dimanches de la Cinémathèque ................................................................................................................5 Pour l’amour de l’Art .......................................................................................................................................10 Cycle Yakuzas ................................................................................................................................................11 Les années Shimkus ......................................................................................................................................14 Amnesty international .....................................................................................................................................16 Viril.e.s............................................................................................................................................................17 Cinéma Littérature ..........................................................................................................................................18 Des courts en hiver.........................................................................................................................................19 -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films,