African American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetics of Relationality: Mobility, Naming, and Sociability in Southeastern Senegal by Nikolas Sweet a Dissertation Submitte

The Poetics of Relationality: Mobility, Naming, and Sociability in Southeastern Senegal By Nikolas Sweet A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee Professor Judith Irvine, chair Associate Professor Michael Lempert Professor Mike McGovern Professor Barbra Meek Professor Derek Peterson Nikolas Sweet [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-3957-2888 © 2019 Nikolas Sweet This dissertation is dedicated to Doba and to the people of Taabe. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The field work conducted for this dissertation was made possible with generous support from the National Science Foundation’s Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant, the Wenner-Gren Foundation’s Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, the National Science Foundation’s Graduate Research Fellowship Program, and the University of Michigan Rackham International Research Award. Many thanks also to the financial support from the following centers and institutes at the University of Michigan: The African Studies Center, the Department of Anthropology, Rackham Graduate School, the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies, the Mellon Institute, and the International Institute. I wish to thank Senegal’s Ministère de l'Education et de la Recherche for authorizing my research in Kédougou. I am deeply grateful to the West African Research Center (WARC) for hosting me as a scholar and providing me a welcoming center in Dakar. I would like to thank Mariane Wade, in particular, for her warmth and support during my intermittent stays in Dakar. This research can be seen as a decades-long interest in West Africa that began in the Peace Corps in 2006-2009. -

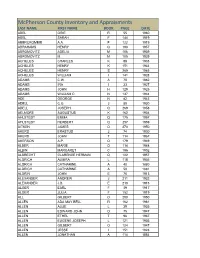

Mcpherson County Inventory and Appraisments LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ABEL ORIE R 55 1960 ABEL SARAH F 144 1919 ABERCROMBIE A.A

McPherson County Inventory and Appraisments LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ABEL ORIE R 55 1960 ABEL SARAH F 144 1919 ABERCROMBIE A.A. F 122 1919 ABRAHAMS HENRY Q 193 1957 ABROMOVITZ ADELIA M 106 1939 ABROMOVITZ M. M 105 1939 ACHILLES CHARLES K 88 1933 ACHILLES HENRY K 151 1934 ACHILLES HENRY S 289 1965 ACHILLES WILLIAM I 141 1928 ADAMS C.W. A 70 1882 ADAMS IRA I 33 1927 ADAMS JOHN H 129 1925 ADAMS WILLIAM C. N 147 1944 ADE GEORGE N 82 1943 ADELL C.G. J 80 1930 ADELL JOSEPH Q 269 1958 AELMORE AUGUSTUS K 162 1934 AHLSTEDT EMMA Q 175 1957 AHLSTEDT HERBERT Q 297 1959 AITKEN JAMES O 270 1950 AKERS ERASTUS J 74 1930 AKERS JOHN T 114 1967 AKERSON A.P. O 179 1949 ALBER MARIE O 114 1948 ALBIN MARGARET C 196 1902 ALBRECHT CLARENCE HERMAN Q 122 1957 ALDRICH ALMIRA L 118 1936 ALDRICH CATHARINE A 40 1880 ALDRICH CATHARINE A 50 1881 ALDRIN JOHN E 76 1913 ALEXANDER ANDREW J 211 1932 ALEXANDER J.B. E 210 1915 ALGER EARL F 39 1917 ALGER JULIA F 152 1919 ALL GILBERT O 290 1950 ALLEN ADA MAY BELL R 162 1961 ALLEN ALLIE L 39 1935 ALLEN EDWARD JOHN O 75 1947 ALLEN ETHEL T 96 1967 ALLEN EUGENE JOSEPH L 121 1936 ALLEN GILBERT O 124 1947 ALLEN JESSE I 151 1928 ALLEN JONATHAN A 114 1884 LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ALLEN LURA ELLEN Q 267 1958 ALLEN MARTHA C 174 1902 ALLEN NORMAN A 7 1878 ALLEN O.D. -

Carolingian Uncial: a Context for the Lothar Psalter

CAROLINGIAN UNCIAL: A CONTEXT FOR THE LOTHAR PSALTER ROSAMOND McKITTERICK IN his famous identification and dating ofthe Morgan Golden Gospels published in the Festschrift for Belle da Costa Greene, E. A. Lowe was quite explicit in his categorizing of Carolingian uncial as the 'invention of a display artist'.^ He went on to define it as an artificial script beginning to be found in manuscripts of the ninth century and even of the late eighth century. These uncials were reserved for special display purposes, for headings, titles, colophons, opening lines and, exceptionally, as in the case ofthe Morgan Gospels Lowe was discussing, for an entire codex. Lowe acknowledged that uncial had been used in these ways before the end of the eighth century, but then it was * natural' not 'artificial' uncial. One of the problems I wish to address is the degree to which Frankish uncial in the late eighth and the ninth centuries is indeed 'artificial' rather than 'natural'. Can it be regarded as a deliberate recreation of a script type, or is it a refinement and elevation in status of an existing book script? Secondly, to what degree is a particular script type used for a particular text type in the early Middle Ages? The third problem, related at least to the first, if not to the second, is whether Frankish uncial, be it natural or artificial, is sufficiently distinctive when used by a particular scriptorium to enable us to locate a manuscript or fragment to one atelier rather than another. This problem needs, of course, to be set within the context of later Carolingian book production, the notions of 'house' style as opposed to 'regional' style and the criteria for locating manuscript production to particular scriptoria in the Frankish kingdoms under the Carolingians that I have discussed elsewhere." It is also of particular importance when considering the Hofschule atehers ofthe mid-ninth century associated with the Emperor Lothar and with King Charles the Bald. -

Names in Toni Morrison's Novels: Connections

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality or this reproduction is dependent upon the quaUty or the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A. Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml48106·1346 USA 313!761·4700 8001521·0600 .. -------------------- ----- Order Number 9520522 Names in Toni Morrison's novels: Connections Clayton, Jane Burris, Ph.D. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1994 Copyright @1994 by Clayton, Jane Burris. -

Destination--Oskaloosa Kjell Nordqvist

Swedish American Genealogist Volume 8 | Number 2 Article 2 6-1-1988 Destination--Oskaloosa Kjell Nordqvist Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nordqvist, Kjell (1988) "Destination--Oskaloosa," Swedish American Genealogist: Vol. 8 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag/vol8/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swedish American Genealogist by an authorized editor of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Destination - Oskaloosa Kjell N ordqvist * During the 19th century many Swedish immigrants participated in and helped develop America's infrastructure as railroad workers and bridge builders. Quite a few labored in the coal mines to produce the fuel for the heavy locomotives which thundered along America's newly constructed railroads. Some of these miners are the main characters in this presentation. On an April day in 1879 the steamship Rollo l,eft the pier in Goteborg to begin its journey across the North Sea to Hull in England. Most of the passengers were emigrants, who from Hull would continue the journey via railway to Liverpool and from there board an Atlantic vessel, destined for America. One of these passengers was Victor Petersson, a 20-year-old son of a furnace foreman living in Brickegarden in Karlskoga. He was accompanied by his 12-year-old sister, Maria. They had informed the emigrant agent that their destination in the new land was Oskaloosa. -

Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License

As of 12:00 am on Thursday, December 14, 2017 Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License Richter Sara May Yes Yes Silver Matthew A Yes Yes Griffiths Stacy M Yes Yes Archer Haylee Nichole Yes Yes Begay Delores A Yes Yes Gray Heather E Yes Yes Pearson Brianna Lee Yes Yes Conlon Tyler Scott Yes Yes Ma Shuang Yes Yes Ott Briana Nichole Yes Yes Liang Guopeng No Yes Jung Chang Gyo Yes Yes Carns Katie M Yes Yes Brooks Alana Marie Yes Yes Richardson Andrew Yes Yes Livingston Derek B Yes Yes Benson Brightstar Yes Yes Gowanlock Michael Yes Yes Denny Racheal N No Yes Crane Beverly A No Yes Paramo Saucedo Jovanny Yes Yes Bringham Darren R Yes Yes Torresdal Jack D Yes Yes Chenoweth Gregory Lee Yes Yes Bolton Isabella Yes Yes Miller Austin W Yes Yes Enriquez Jennifer Benise Yes Yes Jeplawy Joann Rose Yes Yes Harward Callie Ruth Yes Yes Saing Jasmine D Yes Yes Valasin Christopher N Yes Yes Roegge Alissa Beth Yes Yes Tiffany Briana Jekel Yes Yes Davis Hannah Marie Yes Yes Smith Amelia LesBeth Yes Yes Petersen Cameron M Yes Yes Chaplin Jeremiah Whittier Yes Yes Sabo Samantha Yes Yes Gipson Lindsey A Yes Yes Bath-Rosenfeld Robyn J Yes Yes Delgado Alonso No Yes Lackey Rick Howard Yes Yes Brockbank Taci Ann Yes Yes Thompson Kaitlyn Elizabeth No Yes Clarke Joshua Isaiah Yes Yes Montano Gabriel Alonzo Yes Yes England Kyle N Yes Yes Wiman Charlotte Louise Yes Yes Segay Marcinda L Yes Yes Wheeler Benjamin Harold Yes Yes George Robert N Yes Yes Wong Ann Jade Yes Yes Soder Adrienne B Yes Yes Bailey Lydia Noel Yes Yes Linner Tyler Dane Yes Yes -

Shadow Kingdom: Lotharingia and the Frankish World, C.850-C.1050 1. Introduction Like Any Family, the Carolingian Dynasty Which

1 Shadow Kingdom: Lotharingia and the Frankish World, c.850-c.1050 1. Introduction Like any family, the Carolingian dynasty which ruled continental Western Europe from the mid-eighth century until the end of the ninth had its black sheep. Lothar II (855-69) was perhaps the most tragic example. A great-grandson of the famous emperor Charlemagne, he belonged to a populous generation of the family which ruled the Frankish empire after it was divided into three kingdoms – east, west and middle – by the Treaty of Verdun in 843. In 855 Lothar inherited the northern third of the Middle Kingdom, roughly comprising territories between the Meuse and the Rhine, and seemed well placed to establish himself as a father to the next generation of Carolingians. But his line was not to prosper. Early in his reign he had married a noblewoman called Theutberga in order to make an alliance with her family, but a few childless years later attempted to divorce her in order to marry a former lover called Waldrada by whom he already had a son. This was to be Lothar’s downfall, as his uncles Charles the Bald and Louis the German, kings respectively of west and east Francia, enlisted the help of Pope Nicholas I in order to keep him married and childless, and thus render his kingdom vulnerable to their ambitions. In this they were ultimately successful – by the time he died in 869, aged only 34, Lothar’s divorce had become a full-blown imperial drama played out through an exhausting cycle of litigation and posturing which dominated Frankish politics throughout the 860s.1 In the absence of a legitimate heir to take it over, his kingdom was divided between those of his uncles – and with the exception of a short period in the 890s, it never truly existed again as an independent kingdom. -

Rethinking Representations of Slave Life a Historical Plantation Museums

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Louisiana State University Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Rethinking representations of slave life a historical plantation museums: towards a commemorative museum pedagogy Julia Anne Rose Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Julia Anne, "Rethinking representations of slave life a historical plantation museums: towards a commemorative museum pedagogy" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1040. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1040 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. RETHINKING REPRESENTATIONS OF SLAVE LIFE AT HISTORICAL PLANTATION MUSEUMS: TOWARDS A COMMEMORATIVE MUSEUM PEDAGOGY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Julia Anne Rose B.A., State University of New York at Albany, 1980 M.A.T., The George Washington University, 1984 August, 2006 Dedication In memory of my loving sister, Claudia J. Liban ii Acknowledgments I was a young mother with two little boys when I first entertained the idea of pursuing a doctor of philosophy degree in education. -

Karl A. Liljeberg Alias Charles A. Greenlund

Swedish American Genealogist Volume 14 Number 1 Article 3 3-1-1994 Karl A. Liljeberg alias Charles A. Greenlund James E. Erickson C. Eldred Erickson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Erickson, James E. and Erickson, C. Eldred (1994) "Karl A. Liljeberg alias Charles A. Greenlund," Swedish American Genealogist: Vol. 14 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag/vol14/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swedish American Genealogist by an authorized editor of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Karl A. Liljeberg alias Charles A. Greenlund James E. Erickson and C. Eldred Erickson* Authors' note: What follows is ostensibly the story of Karl A. Liljeberg and his immediate family. Admittedly, it is a very ordinary story about very ordinary people. But the reader is encouraged to look beyond the narrative per se and focus instead on its evolution. The importance of this story lies in such things as the basic chronology of discovery that is outlined, the role of chance in bypassing apparent dead ends in the research process that is revealed, the manner in which the father of an illegitimate child is tentatively identified. and the way in which the basic genealogical and family history information is synthesized into a completed whole. The Mystery In the March 199 1 issue of SAG, one of us (JEE) alluded toa five-year- old boy, Karl A. -

African Names and Naming Practices: the Impact Slavery and European

African Names and Naming Practices: The Impact Slavery and European Domination had on the African Psyche, Identity and Protest THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Liseli A. Fitzpatrick, B.A. Graduate Program in African American and African Studies The Ohio State University 2012 Thesis Committee: Lupenga Mphande, Advisor Leslie Alexander Judson Jeffries Copyrighted by Liseli Anne Maria-Teresa Fitzpatrick 2012 Abstract This study on African naming practices during slavery and its aftermath examines the centrality of names and naming in creating, suppressing, retaining and reclaiming African identity and memory. Based on recent scholarly studies, it is clear that several elements of African cultural practices have survived the oppressive onslaught of slavery and European domination. However, most historical inquiries that explore African culture in the Americas have tended to focus largely on retentions that pertain to cultural forms such as religion, dance, dress, music, food, and language leaving out, perhaps, equally important aspects of cultural retentions in the African Diaspora, such as naming practices and their psychological significance. In this study, I investigate African names and naming practices on the African continent, the United States and the Caribbean, not merely as elements of cultural retention, but also as forms of resistance – and their importance to the construction of identity and memory for persons of African descent. As such, this study examines how European colonizers attacked and defiled African names and naming systems to suppress and erase African identity – since names not only aid in the construction of identity, but also concretize a people’s collective memory by recording the circumstances of their experiences. -

Balkan Saints

1 SAINTS OF THE BALKANS Edited by Mirjana Detelić and Graham Jones 2 Table of Contents Mirjana Detelić and Graham Jones, Introduction (3-5) Milena Milin, The beginnings of the cults of Christian martyrs and other saints in the Late Antique central Balkans (6-15) Aleksandar Loma, The contribution of toponomy to an historical topography of saints‟ cults among the Serbs (16-22) Tatjana Subotin-Golubović, The cult of Michael the Archangel in medieval Serbia (23- 30) Danica Popović, The eremitism of St Sava of Serbia (31-41) Branislav Cvetković, The icon in context: Its functional adaptability in medieval Serbia (42-50) Miroslav Timotijević, From saints to historical heroes: The cult of the Despots Branković in the Nineteenth Century (52-69) Jelena Dergenc, The relics of St Stefan Štiljanović (70-80) Gerda Dalipaj, Saint‟s day celebrations and animal sacrifice in the Shpati region of Albania: Reflections of local social structure and identities (81-89) Raĉko Popov, Paraskeva and her „sisters‟: Saintly personification of women‟s rest days and other themes (90-98) Manolis Varvounis, The cult of saints in Greek traditional culture (99-108) Ljupĉo Risteski, The concept and role of saints in Macedonian popular religion (109- 127) Biljana Sikimić, Saints who wind guts (128-161) Mirjam Mencej, Saints as the wolves‟ shepherd (162-184) Mirjana Detelić, Two case studies of the saints in the „twilight zone‟ of oral literature: Petka and Sisin (185-204) Contributors Branislav Cvetković, Regional Museum, Jagodina (Serbia) Gerda Dalipaj, Tirana (Albania) Jelena Dergenc, The National Museum, Belgrade (Serbia) Mirjana Detelić, The SASA Institute for Balkan Studies, Belgrade (Serbia) Aleksandar Loma, Faculty of Philosophy, Belgrade University (Serbia) Mirjam Mencej, Faculty of Philosophy, Ljubljana University (Slovenia) Milena Milin, Faculty of Philosophy, Belgrade University (Serbia) Raĉko Popov, Ethnographic Institute and Museum, Sofia (Bulgaria) Danica Popović, The SASA Institute for Balkan Studies, Belgrade (Serbia) Ljupĉo S. -

THE CONDUCTOR Network to Freedom Program Summer 2005 Issue No

National Park Service The Underground Railroad U.S. Department of the Interior Network To Freedom Program National Capital Region Washington, D.C. The official newsletter of The National Capital Region THE CONDUCTOR Network to Freedom Program Summer 2005 Issue no. 15 2 NPS Unveils New 3 National Trust 4 D.C. Profiles: 5 Mary Mauzy’s Civil War Web Site Lists UGRR Site As Charlotte Forten Nightmare.... Endangered Grimke The official NPS Civil War Web Site The National Trust for Historic Charlotte Forten Grimke (1837 - We still live with the legacy of will enable youth to connect with a Preservation has featured UGRR 1913) was an important African John Brown's Raid. Mary Mauzy, historic national crisis. "We are on this year's list of the 11 most American abolitionist. She was her Armory worker husband, and excited about this new website.... endangered sites in the USA... the granddaughter of.... their son, George, became .... New DC Area Members of the Network to Freedom Program The National Underground second is an NPS park unit Railroad (UGRR) Network to Hampton NHS (Towson, Freedom now has more than MD) which during 200 years 225 members. The Network of enslaved labor had at least to Freedom proudly 75 escapes (surely because of announces new members in the proximity of Baltimore the greater Washington and the Pennsylvania line). metropolitan area determined eligible in In southern Maryland a Indianapolis on April. In number of sites were Virginia, there was one new Coordinators pose in front of the Georgtown accepted: Jefferson Patterson National Historic Landmark in Madison, Indiana.