Carolingian Uncial: a Context for the Lothar Psalter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Kufic Script in Islamic Calligraphy and Its Relevance To

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 A study of Kufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century Enis Timuçin Tan University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Tan, Enis Timuçin, A study of Kufic crs ipt in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/1749 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. A Study ofKufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century. DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ENiS TIMUgiN TAN, GRAD DIP, MCA FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1999 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, expect where due reference has been made in the text. Enis Timucin Tan December 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge with appreciation Dr. Diana Wood Conroy, who acted not only as my supervisor, but was also a good friend to me. I acknowledge all staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, specially Olena Cullen, Liz Jeneid and Associate Professor Stephen Ingham for the variety of help they have given to me. -

The Elements of Abbreviation in Medieval Latin Paleography

The elements of abbreviation in medieval Latin paleography BY ADRIANO CAPPELLI Translated by David Heimann and Richard Kay UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES, 1982 University of Kansas Publications Library Series, 47 The elements of abbreviation in medieval Latin paleography BY ADRIANO CAPPELLI Translated by David Heimann and Richard Kay UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES, 1982 Printed in Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A. by the University of Kansas Printing Service PREFACE Take a foreign language, write it in an unfamiliar script, abbreviating every third word, and you have the compound puzzle that is the medieval Latin manuscript. For over two generations, paleographers have taken as their vade mecum in the decipherment of this abbreviated Latin the Lexicon abbreviaturarum compiled by Adriano Cappelli for the series "Manuali Hoepli" in 1899. The perennial value of this work undoubtedly lies in the alphabetic list of some 14,000 abbreviated forms that comprises the bulk of the work, but all too often the beginner slavishly looks up in this dictionary every abbreviation he encounters, when in nine cases out of ten he could ascertain the meaning by applying a few simple rules. That he does not do so is simply a matter of practical convenience, for the entries in the Lexicon are intelligible to all who read Latin, while the general principles of Latin abbreviation are less easily accessible for rapid consultation, at least for the American student. No doubt somewhere in his notes there is an out line of these rules derived from lectures or reading, but even if the notes are at hand they are apt to be sketchy; for reference he would rather rely on the lengthier accounts available in manuals of paleography, but more often than not he has only Cappelli's dictionary at his elbow. -

Early Medieval Europe

Early Medieval Europe 1 Early Medieval Sites in Europe 2 Figure 16-2 Pair of Merovingian looped fibulae, from Jouy-le-Comte, France, mid-sixth century. Silver gilt worked in filigree, with inlays of garnets and other stones, 4” high. Musée d’Archéologie nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye. 3 Heraldic Motifs Figure 16-3 Purse cover, from the Sutton Hoo ship burial in Suffolk, England, ca. 625. Gold, glass, and cloisonné garnets, 7 1/2” long. British Museum, London. 4 5 Figure 16-4 Animal-head post, from the Viking ship burial, Oseberg, Norway, ca. 825. Wood, head 5” high. University Museum of National Antiquities, Oslo. 6 Figure 16-5 Wooden portal of the stave church at Urnes, Norway, ca. 1050–1070. 7 Figure 16-6 Man (symbol of Saint Matthew), folio 21 verso of the Book of Durrow, possibly from Iona, Scotland, ca. 660–680. Ink and tempera on parchment, 9 5/8” X 6 1/8”. Trinity College Library, Dublin. 8 Figure 16-1 Cross-inscribed carpet page, folio 26 verso of the Lindisfarne Gospels, from Northumbria, England, ca. 698–721. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1 1/2” X 9 1/4”. British Library, London. 9 Figure 16-7 Saint Matthew, folio 25 verso of the Lindisfarne Gospels, from Northumbria, England, ca. 698–721. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1 1/2” X 9 1/4”. British Library, London. 10 Figure 16-8 Chi-rho-iota (XPI) page, folio 34 recto of the Book of Kells, probably from Iona, Scotland, late eighth or early ninth century. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1” X 9 1/2”. -

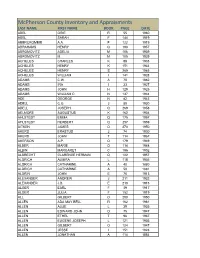

Mcpherson County Inventory and Appraisments LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ABEL ORIE R 55 1960 ABEL SARAH F 144 1919 ABERCROMBIE A.A

McPherson County Inventory and Appraisments LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ABEL ORIE R 55 1960 ABEL SARAH F 144 1919 ABERCROMBIE A.A. F 122 1919 ABRAHAMS HENRY Q 193 1957 ABROMOVITZ ADELIA M 106 1939 ABROMOVITZ M. M 105 1939 ACHILLES CHARLES K 88 1933 ACHILLES HENRY K 151 1934 ACHILLES HENRY S 289 1965 ACHILLES WILLIAM I 141 1928 ADAMS C.W. A 70 1882 ADAMS IRA I 33 1927 ADAMS JOHN H 129 1925 ADAMS WILLIAM C. N 147 1944 ADE GEORGE N 82 1943 ADELL C.G. J 80 1930 ADELL JOSEPH Q 269 1958 AELMORE AUGUSTUS K 162 1934 AHLSTEDT EMMA Q 175 1957 AHLSTEDT HERBERT Q 297 1959 AITKEN JAMES O 270 1950 AKERS ERASTUS J 74 1930 AKERS JOHN T 114 1967 AKERSON A.P. O 179 1949 ALBER MARIE O 114 1948 ALBIN MARGARET C 196 1902 ALBRECHT CLARENCE HERMAN Q 122 1957 ALDRICH ALMIRA L 118 1936 ALDRICH CATHARINE A 40 1880 ALDRICH CATHARINE A 50 1881 ALDRIN JOHN E 76 1913 ALEXANDER ANDREW J 211 1932 ALEXANDER J.B. E 210 1915 ALGER EARL F 39 1917 ALGER JULIA F 152 1919 ALL GILBERT O 290 1950 ALLEN ADA MAY BELL R 162 1961 ALLEN ALLIE L 39 1935 ALLEN EDWARD JOHN O 75 1947 ALLEN ETHEL T 96 1967 ALLEN EUGENE JOSEPH L 121 1936 ALLEN GILBERT O 124 1947 ALLEN JESSE I 151 1928 ALLEN JONATHAN A 114 1884 LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ALLEN LURA ELLEN Q 267 1958 ALLEN MARTHA C 174 1902 ALLEN NORMAN A 7 1878 ALLEN O.D. -

Old Cyrillic in Unicode*

Old Cyrillic in Unicode* Ivan A Derzhanski Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences [email protected] The current version of the Unicode Standard acknowledges the existence of a pre- modern version of the Cyrillic script, but its support thereof is limited to assigning code points to several obsolete letters. Meanwhile mediæval Cyrillic manuscripts and some early printed books feature a plethora of letter shapes, ligatures, diacritic and punctuation marks that want proper representation. (In addition, contemporary editions of mediæval texts employ a variety of annotation signs.) As generally with scripts that predate printing, an obvious problem is the abundance of functional, chronological, regional and decorative variant shapes, the precise details of whose distribution are often unknown. The present contents of the block will need to be interpreted with Old Cyrillic in mind, and decisions to be made as to which remaining characters should be implemented via Unicode’s mechanism of variation selection, as ligatures in the typeface, or as code points in the Private space or the standard Cyrillic block. I discuss the initial stage of this work. The Unicode Standard (Unicode 4.0.1) makes a controversial statement: The historical form of the Cyrillic alphabet is treated as a font style variation of modern Cyrillic because the historical forms are relatively close to the modern appearance, and because some of them are still in modern use in languages other than Russian (for example, U+0406 “I” CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER I is used in modern Ukrainian and Byelorussian). Some of the letters in this range were used in modern typefaces in Russian and Bulgarian. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Web Typography │ 2 Table of Content

Imprint Published in January 2011 Smashing Media GmbH, Freiburg, Germany Cover Design: Ricardo Gimenes Editing: Manuela Müller Proofreading: Brian Goessling Concept: Sven Lennartz, Vitaly Friedman Founded in September 2006, Smashing Magazine delivers useful and innovative information to Web designers and developers. Smashing Magazine is a well-respected international online publication for professional Web designers and developers. Our main goal is to support the Web design community with useful and valuable articles and resources, written and created by experienced designers and developers. ISBN: 978-3-943075-07-6 Version: March 29, 2011 Smashing eBook #6│Getting the Hang of Web Typography │ 2 Table of Content Preface The Ails Of Typographic Anti-Aliasing 10 Principles For Readable Web Typography 5 Principles and Ideas of Setting Type on the Web Lessons From Swiss Style Graphic Design 8 Simple Ways to Improve Typography in Your Designs Typographic Design Patterns and Best Practices The Typography Dress Code: Principles of Choosing and Using Typefaces Best Practices of Combining Typefaces Guide to CSS Font Stacks: Techniques and Resources New Typographic Possibilities with CSS 3 Good Old @Font-Face Rule Revisted The Current Web Font Formats Review of Popular Web Font Embedding Services How to Embed Web Fonts from your Server Web Typography – Work-arounds, Tips and Tricks 10 Useful Typography Tools Glossary The Authors Smashing eBook #6│Getting the Hang of Web Typography │ 3 Preface Script is one of the oldest cultural assets. The first attempts at written expressions date back more than 5,000 years ago. From the Sumerians cuneiform writing to the invention of the Gutenberg printing press in Medieval Germany up to today՚s modern desktop publishing it՚s been a long way that has left its impact on the current use and practice of typography. -

JAF Herb Specimen © Just Another Foundry, 2010 Page 1 of 9

JAF Herb specimen © Just Another Foundry, 2010 Page 1 of 9 Designer: Tim Ahrens Format: Cross platform OpenType Styles & weights: Regular, Bold, Condensed & Bold Condensed Purchase options : OpenType complete family €79 Single font €29 JAF Herb Webfont subscription €19 per year Tradition ist die Weitergabe des Feuers und nicht die Anbetung der Asche. Gustav Mahler www.justanotherfoundry.com JAF Herb specimen © Just Another Foundry, 2010 Page 2 of 9 Making of Herb Herb is based on 16th century cursive broken Introducing qualities of blackletter into scripts and printing types. Originally designed roman typefaces has become popular in by Tim Ahrens in the MA Typeface Design recent years. The sources of inspiration range course at the University of Reading, it was from rotunda to textura and fraktur. In order further refined and extended in 2010. to achieve a unique style, other kinds of The idea for Herb was to develop a typeface blackletter were used as a source for Herb. that has the positive properties of blackletter One class of broken script that has never but does not evoke the same negative been implemented as printing fonts is the connotations – a type that has the complex, gothic cursive. Since fraktur type hardly ever humane character of fraktur without looking has an ‘italic’ companion like roman types few conservative, aggressive or intolerant. people even know that cursive blackletter As Rudolf Koch illustrated, roman type exists. The only type of cursive broken script appears as timeless, noble and sophisticated. that has gained a certain awareness level is Fraktur, on the other hand, has different civilité, which was a popular printing type in qualities: it is displayed as unpretentious, the 16th century, especially in the Netherlands. -

A Collection of Mildly Interesting Facts About the Little Symbols We Communicate With

Ty p o g raph i c Factettes A collection of mildly interesting facts about the little symbols we communicate with. Helvetica The horizontal bars of a letter are almost always thinner than the vertical bars. Minion The font size is approximately the measurement from the lowest appearance of any letter to the highest. Most of the time. Seventy-two points equals one inch. Fridge256 point Cochin most of 50the point Zaphino time Letters with rounded bottoms don’t sit on the baseline, but slightly below it. Visually, they would appear too high if they rested on the same base as the squared letters. liceAdobe Caslon Bold UNITED KINGDOM UNITED STATES LOLITA LOLITA In Ancient Rome, scribes would abbreviate et (the latin word for and) into one letter. We still use that abbreviation, called the ampersand. The et is still very visible in some italic ampersands. The word ampersand comes from and-per-se-and. Strange. Adobe Garamond Regular Adobe Garamond Italic Trump Mediaval Italic Helvetica Light hat two letters ss w it cam gue e f can rom u . I Yo t h d. as n b ha e rt en ho a s ro n u e n t d it r fo w r s h a u n w ) d r e e m d a s n o r f e y t e t a e r b s , a b s u d t e d e e n m t i a ( n l d o b s o m a y r S e - d t w A i e t h h t t , h d e n a a s d r v e e p n t m a o f e e h m t e a k i i l . -

Charlemagne's Heir

Charlemagne's Heir New Perspectives on the Reign of Louis the Pious (814-840) EDITED BY PETER' GOD MAN AND ROGER COLLINS CLARENDON PRESS . OXFORD 1990 5 Bonds of Power and Bonds of Association in the Court Circle of Louis the Pious STUART AIRLIE I TAKE my text from Thegan, from the well-known moment in his Life of Louis the Pious when the exasperated chorepiscopus of Trier rounds upon the wretched Ebbo, archbishop of Reims: 'The king made you free, not noble, since that would be impossible." I am not concerned with what Thegan's text tells us about concepts of nobility in the Carolingian world. That question has already been well handled by many other scholars, including JaneMartindale and Hans-Werner Goetz.! Rather, I intend to consider what Thegan's text, and others like it, can tell us about power in the reign of Louis the Pious. For while Ebbo remained, in Thegan's eyes, unable to transcend his origins, a fact that his treacherous behaviour clearly demonstrated, politically (and cultur- ally, one might add) Ebbo towered above his acid-tongued opponent. He was enabled to do this through his possession of the archbishopric of Reims and he had gained this through the largess of Louis the Pious. If neither Louis nor Charlemagne, who had freed Ebbo, could make him noble they could, thanks to the resources of patronage at their disposal, make him powerful, one of the potentes. It was this mis-use, as he saw it, of royal patronage that worried Thegan and it worried him because he thought that the rise of Ebbo was not a unique case. -

Destination--Oskaloosa Kjell Nordqvist

Swedish American Genealogist Volume 8 | Number 2 Article 2 6-1-1988 Destination--Oskaloosa Kjell Nordqvist Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nordqvist, Kjell (1988) "Destination--Oskaloosa," Swedish American Genealogist: Vol. 8 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag/vol8/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swedish American Genealogist by an authorized editor of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Destination - Oskaloosa Kjell N ordqvist * During the 19th century many Swedish immigrants participated in and helped develop America's infrastructure as railroad workers and bridge builders. Quite a few labored in the coal mines to produce the fuel for the heavy locomotives which thundered along America's newly constructed railroads. Some of these miners are the main characters in this presentation. On an April day in 1879 the steamship Rollo l,eft the pier in Goteborg to begin its journey across the North Sea to Hull in England. Most of the passengers were emigrants, who from Hull would continue the journey via railway to Liverpool and from there board an Atlantic vessel, destined for America. One of these passengers was Victor Petersson, a 20-year-old son of a furnace foreman living in Brickegarden in Karlskoga. He was accompanied by his 12-year-old sister, Maria. They had informed the emigrant agent that their destination in the new land was Oskaloosa. -

Handwriting Toward a Minuscule Alphabet, It Is Written Upright and Is Considered a Majuscule Form

There is much to say about the history of writing. To encapsulate the highlights in an essay by this short essay, it is important to note that the dialectic between formal and informal Jerri-Jo Idarius styles of writing led to periods of degeneration and periods of reform and also to the differentiation between what we refer to as caps and small letters, known technically as majuscules and minuscules. The Roman formal majuscule scripts follow: Although the ascenders and descenders of the half-uncial represent the movement Handwriting toward a minuscule alphabet, it is written upright and is considered a majuscule form. is a craft in which everyone participates, After the fall of Rome, various regional styles developed in Europe but in the 8th yet few people know much about its tradition century King Charlemagne instituted one script throughout the monasteries of Europe or evolution. From the view of a calligrapher* to help unite his empire. This style, known as Carolingian, related to the Roman who has studied and mastered tradi- half uncial and Roman cursive, is the first truly minuscule alphabet. Its beauti- tional forms of handwriting, this lack of ful letters can be written straight or at an angle. A simply drawn form of caps called education is a sign of cultural loss. Most versals appeared in manuscripts of this era. elementary school teachers feel inadequate to teach penmanship, and cannot explain the relationship between the cursive Roman Square Caps (Capitalis Quadrata) handwriting they have to teach and the printed letters they see in books. Since Rustic handwriting is so intimately connected to Uncial self-image, and since most people are (used for Bibles and sacred texts) unhappy with the results of their learning, versals it is common to hear, “I hate my writing!” Carolingian minuscule & or “I never learned to write.” They don’t Medieval scripts are popularly described as blackletter, due to the predomi- know what to do about it.