Fiscal Federalism and the Dependency of Atlantic Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why the Battle for IKEA's New Atlantic Canada Store Was Over Before It

BUSINESS ATTRACTION The Big Deal Why the battle for IKEA’s new Atlantic Canada store was over before it started By Stephen Kimber atlanticbusinessmagazine.com | Atlantic Business Magazine 119 Date:16-04-20 Page: 119.p1.pdf consumers in the Halifax area, but it’s also in the crosshairs of a web of major highways that lead to and from every populated nook and cranny in Nova Scotia, not to forget New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, making it a potential shopping destination for close to two million Maritimers. No wonder its 500-acre site already boasts 1.3 million square feet of shopaholic heaven with over 100 retailers and services, including five of those anchor-type destinations: Walmart, Home Depot, Costco, Canadian Tire and Cineplex Cinemas. Glenn Munro was apologetic. I’d been All it needed was an IKEA. calling and emailing him to follow up on January’s announcement that IKEA — the iconic Swedish furniture retailer with 370 stores and $46.6 billion in sales worldwide y now, the IKEA creation last year — would build a gigantic (for us story has morphed into myth: Bin 1947, Ingvar Kamprad, at least) $100-million, 328,000-square- an eccentric, dyslexic 17-year-old foot retail store in Dartmouth Crossing. He Swedish farm boy, launched a mail-order company called IKEA. hadn’t responded. He’d invented the name using his initials and his home district. Soon after, he also invented the “flat I wanted to know how and why pack” to more efficiently package IKEA had settled on Halifax and and ship his modernist build-it- not, say, Moncton as the site for 328,000 yourself furniture. -

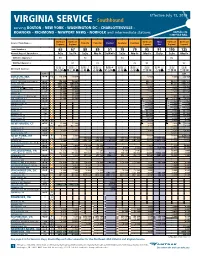

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Atlantic Maritimes Explorer by Rail | Montreal to Halifax

ATLANTIC MARITIMES EXPLORER BY RAIL | MONTREAL TO HALIFAX Atlantic Maritimes Explorer by Rail | Montreal to Halifax Eastern Canada Rail Vacation 8 Days / 7 Nights Montreal to Halifax Priced at USD $2,853 per person Prices are per person and include all taxes. Child age 10 yrs & under INTRODUCTION Experience the best of Montreal, Quebec City, Prince Edward Island in just over a week on this Atlantic Maritimes Explorer Train Trip. Discover Canada as you've never seen it before on a trip with VIA Rail through the Atlantic and Maritime provinces. Witness the dynamic landscapes change from cosmopolitan cities to quirky towns and enjoy your choice of tours in Montreal and Charlottetown. From wandering the local food market on foot to cruising for lobster by boat, each moment is as adventurous as the next. Itinerary at a Glance DAY 1 Arrive Montreal DAY 2 Montreal | Day Tour to Quebec City & Montmorency Falls DAY 3 Montreal | Freedom of Choice - Choose 1 of 3 Excursions Montreal to Charlottetown| VIA Rail Option 1. Montreal Half Day Sightseeing Tour Option 2 Walking Tour of Old Montreal Option 3 Beyond the Market Food Walking Tour DAY 4 Arrive Charlottetown | VIA Rail + Private Transfer DAY 5 Charlottetown | Island Drives & Anne of Green Gables Tour DAY 6 Charlottetown | Freedom of Choice - Choose 1 of 2 Excursions Option 1. Morning Lobster Cruise Option 2. Morning Charlottetown Highlights Tour Charlottetown to Halifax| Private Transfer Start planning your vacation in Canada by contacting our Canada specialists Call 1 800 217 0973 Monday - Friday 8am - 5pm Saturday 8.30am - 4pm Sunday 9am - 5:30pm (Pacific Standard Time) Email [email protected] Web canadabydesign.com Suite 1200, 675 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, BC, V6B 1N2, Canada 2021/06/14 Page 1 of 6 ATLANTIC MARITIMES EXPLORER BY RAIL | MONTREAL TO HALIFAX DAY 7 Halifax | Freedom of Choice - Choose 1 of 4 Excursions Option 1. -

Replacing Amtrak: Privatization, Regionalization, and Liquidation

P o l i c y S t u d y N o . 2 3 5 , O c t o b e r 1 9 9 7 RReeppllaacciinngg AAmmttrraakk:: A Blueprint for Sustainable Passenger Rail Service by Joseph Vranich EXECUTIVE SUMMARY mtrak is a failed national experiment. By its own admission, Amtrak is headed for bankruptcy unless Washington provides another multi-billion-dollar bail-out. Another federal rescue is A unjustified considering that federal and state subsidies to Amtrak since its inception in 1971 are nearing $22.5 billion, an amount out of proportion to Amtrak’s usefulness in most of the nation. The federal government does not run a national airline. It doesn’t operate a national bus company. There’s no justification for a national railroad passenger operation. America needs passenger trains in selected areas, but doesn’t need Amtrak’s antiquated route system, poor service, unreasonable operating deficits, and capital investment program with low rates of return. Amtrak’s failures result in part because it is a public monopoly—the very type of organization least able to innovate. This study reveals an Amtrak credibility crisis in the way it reports ridership figures, glosses over dwindling market share, understates subsidies, issues misleading cost-recovery claims, offers doubtful promises regarding high-speed rail, lacks proper authority for the freight business it recently launched, and misrepresents privatization as its applies to Amtrak. It’s time to liquidate Amtrak, privatize and regionalize parts of it, permit alternative operators to transform some long-distance trains into land-cruise trains, and stop service on hopeless routes. -

Regional Rail

STATION LOCATIONS CONNECTING SERVICES * SATURDAYS, SUNDAYS and MAJOR HOLIDAYS PHILADELPHIA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TERMINALS E and F 37, 108, 115 )DUH 6HUYLFHV 7UDLQ1XPEHU AIRPORT INFORMATION AIRPORT TERMINALS C and D 37, 108, 115 =RQH Ê*Ë6WDWLRQV $0 $0 $0 $0 $0 $0 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 $0 D $LUSRUW7HUPLQDOV( ) TERMINAL A - EAST and WEST AIRPORT TERMINAL B 37, 108, 115 REGIONAL RAIL AIRPORT $LUSRUW7HUPLQDOV& ' D American Airlines International & Caribbean AIRPORT TERMINAL A EAST 37, 108, 115 D $LUSRUW7HUPLQDO% British Airways AIRPORT TERMINAL A WEST 37, 108, 115 D $LUSRUW7HUPLQDO$ LINE EASTWICK (DVWZLFN Qatar Airways 37, 68, 108, 115 To/From Center City Philadelphia D 8511 Bartram Ave & D 3HQQ0HGLFLQH6WDWLRQ Eastern Airlines PENN MEDICINE STATION & DDWK6WUHHW6WDWLRQ ' TERMINAL B 3149 Convention Blvd 40, LUCY & DD6XEXUEDQ6WDWLRQ ' 215-580-6565 Effective September 5, 2021 & DD-HIIHUVRQ6WDWLRQ ' American Airlines Domestic & Canadian service MFL, 9, 10, 11, 13, 30, 31, 34, 36, 30th STREET STATION & D7HPSOH8QLYHUVLW\ The Philadelphia Marketplace 44, 49, 62, 78, 124, 125, LUCY, 30th & Market Sts Amtrak, NJT Atlantic City Rail Line • Airport Terminals E and F D :D\QH-XQFWLRQ ² ²² ²² ²² ² ² ² Airport Marriott Hotel SUBURBAN STATION MFL, BSL, 2, 4, 10, 11, 13, 16, 17, DD)HUQ5RFN7& ² 27, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 38, 44, 48, 62, • Airport Terminals C and D 16th St -

30 Halifax-Montreal.Pdf

Effective October 16, 2019 / En vigueur à compter du 16 octobre 2019 Atlantic Canada Available in the service car. / OffertAvailable dans la in voiture-services. the Service car. HALIFAX MONTRÉAL TRAIN 15 7 14 7 DAYS / JOURS 1234567 1234567 / OCEAN / OCEAN / NAME NOM OCÉAN OCÉAN Halifax, NS AT / HA DP 13:00 AR 17:51 Truro 14:31 16:22 Springhill Jct. ★ 15:43 15:03 Amherst, NS 16:08 14:42 Sackville, NB 16:25 14:26 AR 17:17 DP 13:38 Moncton DP 17:32 7 AR 13:23 6 Rogersville ★ 18:43 5 12:15 4 JOUR 1 JOUR 3 Miramichi 19:37 / 11:23 Bathurst 21:28 12 09:37 DAY 7 Petit Rocher ★ 21:49 09:10 6 5 4 Jacquet River ★ 22:12 08:47 2 JOUR / 23 Charlo ★ 22:36 08:23 1 Campbellton, NB AT / HA 23:18 07:48 DAY Matapédia, QC ET / HE 22:52 06:10 Causapscal ★ 23:40 05:23 Amqui 00:02 05:03 Sayabec ★ 00:22 04:40 Mont-Joli 01:26 03:39 Rimouski 02:01 03:01 Trois-Pistoles ★ 03:04 01:55 Rivière-du-Loup 03:53 01:13 7 6 La Pocatière 04:36 5 00:28 4 JOUR 2 JOUR Montmagny ★ 05:10 / 23:40 23 AR 06:13 1 DP 22:49 Sainte-Foy* DAY 7 DP 06:28 AR 22:34 6 5 4 Drummondville 08:36 20:47 1 JOUR 3 / Saint-Hyacinthe 09:15 19:58 12 Saint-Lambert 09:50 19:25 DAY Montréal, QC ET / HE AR 10:03 DP 19:00 ★ Stops on request when traveller is seen by train staff. -

Source Atlantic Company Contacts Sheet

Company Contacts HEAD OFFICE NEW BRUNSWICK Saint John Halifax Millennium Welding Supply BetterBaths Source Atlantic Bathurst 11 McIlvenn Drive 3630 Strawberry Hill 331 Chesley Drive Power Transmission Saint John, NB E2J 4Y6 P.O. Box 9499, Station A P.O. Box 967 1967 Miramichi Avenue Tel: 506.696.7018 Halifax, NS B3K 5S3 Bathurst, NB E2A 1Y7 Fax: 506.696.3221 Tel: 902.494.5266 Saint John, NB E2L 4E4 Tel: 506.548.4411 Fax: 902.494.5281 Tel: 506.632.1000 Fax: 506.546.8481 Sussex www.betterbaths.ca Fax: 506.633.1000 Power Transmission Moncton Mt. Uniacke Toll Free: 1.888.846.7637 7 Turner Court Thornes Sussex, NB E4E 2S1 Mobile Valve After Hours: 506.632.1000 320 Edinburgh Drive Tel: 506.432.2910 140-142 Old Windsor Hwy. www.sourceatlantic.ca Moncton, NB E1E 2L1 Fax: 506.432.2911 P.O. Box 90 Tel: 506.859.5377 Mt. Uniacke, NS B0N 1Z0 Fax: 506.859.5379 Tracy Tel: 902.866.0719 Toll Free: 1.800.563.3336 Mobile Valve Fax: 902.866.1091 Saint John 16 Mast Road Toll Free: 1.877.825.8776 P.O. Box 147 Source Atlantic Tracy, NB E5L 2W1 N.L. Eldridge 331 Chesley Drive Tel: 506.368.7311 140-142 Old Windsor Hwy. P.O. Box 967 Fax: 506.368.7845 Saint John, NB E2L 4E4 P.O. Box 90 Toll Free: 1.877.825.8776 Tel: 506.632.1000 Mt. Uniacke, NS B0N 1Z0 Fax: 506.633.1000 NOVA SCOTIA Tel: 902.866.0719 Toll Free: 1.888.846.7637 Fax: 902.866.1091 Toll Free: 1.800.567.1965 Hydraulics, Rigging & Rubber Dartmouth 331 Chesley Drive Source Atlantic Sydney P.O. -

1 Atlantic Immigration Pilot Designated Employer List: The

Atlantic Immigration Pilot Designated Employer List: The following is a list of employers designated in New Brunswick through the Atlantic Immigration Pilot. This list does not indicate that these employers are hiring. To find current job vacancies got to www.nbjobs.ca. Liste des employeurs désignés Voici la liste des employeurs désignés sous le Projet pilote en matière d’immigration au Canada atlantique. Cette liste ne signifie pas que ces employeurs recrutent présentement.ss Pour les offres d’emploi, visitez le www.emploisnb.ca. Employer Name 3D Property Management 670807 NB Inc (Dépaneur Needs Caraquet & Shippagan) 693666 NB Inc. A & J Hanna Construction Ltd (Fredericton) A&W Miramichi (630883 NB Inc) A.C. Sharkey's Pub & Grill (Florenceville-Bristol) A.N.D. Communications A.R.Rietzel Landscaping Ltd Acadia Pizza Donair / Korean Restaurant (Dieppe) Acadia Veterinary Hospital Accor Hotels Global Reservation Centre Acorn Restaurant / Mads Truckstop (Lake George) Admiral's Quay B&B (Yang Developments Ltd.) Adorable Chocolat Inc Adrice Cormier Ltd Agence Résidentielle Restigouche Airport General Store (649459 NB Ltd) Airport Inn AirVM Albert's Draperies Alexandru & Camelia Trucking All Needs Special Care Inc. Allen, Paquet & Arseneau Allen's Petro Canada & Grocery (Allen's Enterprise Inc.) AL-Pack Amsterdam Inn & Suites Sussex (deWinter Brothers Ltd.) Andrei Chartovich 1 Employer Name Andrei Master Tailors Ltd Apex Industries Inc Appcast Armour Transport Inc Arom Chinese Cuisine Fredericton (655749 N.B. Ltd.) Asian Garden Indian Restaurant Moncton (Bhatia Brothers Ltd) Aspen University Association Multiculturelle du Restigouche Assurion Canada Inc Asurion Atelier Gérard Beaulieu Atlantic Ballet of Canada Atlantic Controls (Division of Laurentide Controls) Atlantic Home Improvement (656637 NB Inc) Atlantic Lottery Corporation Atlantic Pacific Transport Ltd. -

2014 Maine State Rail Plan

Maine State Rail Plan TABLE OF CONTENTSview Chapter 1 Framework of the Maine State Rail Plan 1.1 Purpose of the State Rail Plan 1.1 1.2 Visions, Goals, Objectives of the Maine State Rail Plan 1.3 1.3 Transportation and Rail Planning in Maine 1.6 . Figure 1-1: MaineDOT Organizational Chart 1.7 . Figure 1-2: Maine’s MPO Areas 1.10 . Figure 1-3: Regional Planning and Development Councils 1.11 1.4 Public and Stakeholder Involvement 1.12 1.5 Review of Freight and Passenger Rail Planning Studies 1.17 1.6 Evaluation Criteria 1.18 Chapter 2 Freight Rail System 2.1 Overview 2.1 . Figure 2-1: North American Class I Rail Connections 2.2 . Figure 2-2: Map of MM&A Abandonment 2.6 . Figure 2-3: State of Maine Owned Rail Status 2.10 2.2 Freight Rail Industry Development 2.10 2.3 Maine’s Freight Railroad Facilities 2.12 2.4 International, National and Regional Context 2.21 . Figure 2-4: Canadian Class I Connections to Maine System 2.21 . Figure 2-5: Northeast U.S. Rail Freight System 2.22 . Figure 2-6: NS, CP, PAS and PAR Corridors 2.23 . Figure 2-7: Railroad Return on Investment and Cost of Capital 2.24 2.5 Freight Rail Issues and System Constraints 2.24 . Figure 2-8: Estimated National Highway System Peak-Period Congestion 2.25 . Figure 2-9: Estimated Rail Freight Service Levels, 2035 2.25 . Figure 2-10: Rail Clearance and Weight Constraints 2.28 . -

Robert J. Keach V. Canadian Pacific Railway

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF MAINE In re: Chapter 11 MONTREAL MAINE & ATLANTIC Case No. 13-10670 RAILWAY, LTD. Debtor ROBERT J. KEACH, solely in his capacity as the estate representative of the post-effective date estate of MONTREAL MAINE & ATLANTIC RAILWAY, LTD. Adv. Proc. No. 14-1001 Plaintiff v. CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILWAY COMPANY and SOO LINE RAILROAD COMPANY Defendants ORDER ON PLAINTIFF’S MOTION FOR A PROTECTIVE ORDER Plaintiff Robert J. Keach, solely in his capacity as the estate representative of the post-effective date estate of Montreal Maine & Atlantic Railway, Ltd., moved this court for the entry of a protective order and an award of fees and costs in regard to the deposition notice served on the estate representative under Fed. R. Civ. P. 30(b)(6) by defendants Canadian Pacific Railway Company and Soo Line Railroad Company (Docket Entry 1 “D.E.” 461).1 After due consideration of the motion, the defendants’ opposition, the estate representative’s reply, and the arguments of counsel at the October 8, 2019 hearing, the court denies the relief sought by the estate representative for the reasons set forth below. Background The estate representative, as the plaintiff in this case, seeks damages from the defendants of more than $50,000,000 (Third Amended Complaint dated August 8, 2016, at D.E. 230, ¶¶ 17, 18, 106, 110, and 118). By a notice of deposition dated August 9, 2019 a copy of which is attached as Exhibit A to the September 24, 2019, Affidavit of Mr. Keach (D.E. 461-1), the defendants indicated their intent to depose the “plaintiff” of this adversary proceeding pursuant to Rule 30(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. -

National Closing Ceremony Information Atlantic Region

Please join us on “Walk Day”, Sunday, May 31st for our virtual ceremonies. You can find out if your region/walk is hosting an opening ceremony below and learn more about our National Closing Ceremony as well. NATIONAL CLOSING CEREMONY INFORMATION Please feel free to join our National Closing Ceremonies for a word from our CEO, Kelly Grover on our CF Canada Facebook page at 4pm EDT/ 3pm CDT/ 1pm PDT/ 5pm ADT ATLANTIC REGION: VIRTUAL OPENING CEREMONY INFORMATION Walk Location: All Atlantic Walk Locations Time: 10:30 a.m. ADT Overview: Although not physically together, our Walks have joined forces to create a virtual Regional Opening Ceremonies for the 2020 Walk! The video will premiere on both our YouTube channel and Atlantic Region Facebook Page and will feature some amazing people within the CF community! We will be highlighting an amazing CF warrior, acknowledging some awesome people, listening to some music and much more - so we hope to see you there. Learn more: Details will be sent via email to all registered walkers on Saturday May 30, posted on our Regional Facebook page, as well as included on all the Atlantic Walk pages listed on the CF Canada community event pages. QUEBEC: VIRTUAL OPENING CEREMONY INFORMATION Walk Location: All Quebec Walk locations Time: 10:00am EST, 10 h Overview: Let’s bring together the whole province to celebrate this different, but incredible Walk. We will take the time to talk to some of our volunteers and walk participant and finally reveal the amount raised in Quebec. Learn more: Fibrose kystique Canada – Division Québec Facebook page BC/YUKON: VIRTUAL OPENING CEREMONY INFORMATION Walk Location: All BC/Yukon Walk Locations Time: 12:30 PM PST Overview: hear from our Walk coordinators, announcement of totals raised, message from our regional manager and fund development associate.