Replacing Amtrak: Privatization, Regionalization, and Liquidation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why the Battle for IKEA's New Atlantic Canada Store Was Over Before It

BUSINESS ATTRACTION The Big Deal Why the battle for IKEA’s new Atlantic Canada store was over before it started By Stephen Kimber atlanticbusinessmagazine.com | Atlantic Business Magazine 119 Date:16-04-20 Page: 119.p1.pdf consumers in the Halifax area, but it’s also in the crosshairs of a web of major highways that lead to and from every populated nook and cranny in Nova Scotia, not to forget New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, making it a potential shopping destination for close to two million Maritimers. No wonder its 500-acre site already boasts 1.3 million square feet of shopaholic heaven with over 100 retailers and services, including five of those anchor-type destinations: Walmart, Home Depot, Costco, Canadian Tire and Cineplex Cinemas. Glenn Munro was apologetic. I’d been All it needed was an IKEA. calling and emailing him to follow up on January’s announcement that IKEA — the iconic Swedish furniture retailer with 370 stores and $46.6 billion in sales worldwide y now, the IKEA creation last year — would build a gigantic (for us story has morphed into myth: Bin 1947, Ingvar Kamprad, at least) $100-million, 328,000-square- an eccentric, dyslexic 17-year-old foot retail store in Dartmouth Crossing. He Swedish farm boy, launched a mail-order company called IKEA. hadn’t responded. He’d invented the name using his initials and his home district. Soon after, he also invented the “flat I wanted to know how and why pack” to more efficiently package IKEA had settled on Halifax and and ship his modernist build-it- not, say, Moncton as the site for 328,000 yourself furniture. -

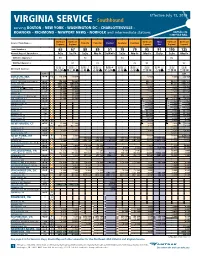

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

On the Brink: 2021 Outlook for the Intercity Bus Industry in the United States

On the Brink: 2021 Outlook for the Intercity Bus Industry in the United States BY JOSEPH SCHWIETERMAN, BRIAN ANTOLIN & CRYSTAL BELL JANUARY 30, 2021 CHADDICK INSTITUTE FOR METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT AT DEPAUL UNIVERSITY | POLICY SERIES THE STUDY TEAM AUTHORS BRIAN ANTOLIN, JOSEPH P. SCHWIETERMAN AND CRYSTAL BELL CARTOGRAPHY ALL TOGETHER STUDIO AND GRAPHICS ASSISTING MICHAEL R. WEINMAN AND PATRICIA CHEMKA SPERANZA OF PTSI TRANSPORTATION CONTRIBUTORS DATA KIMBERLY FAIR AND MITCH HIRST TEAM COVER BOTTOM CENTER: ANNA SHVETS; BOTTOM LEFT: SEE CAPTION ON PAGE 1; PHOTOGRAPHY TOP AND BOTTOM RIGHT: CHADDICK INSTITUTE The Chaddick Insttute does not receive funding from intercity bus lines or suppliers of bus operators. This report was paid for using general operatng funds. For further informaton, author bios, disclaimers, and cover image captons, see page 20. JOIN THE STUDY TEAM FOR A WEBINAR ON THIS STUDY: Friday, February 19, 2021 from noon to 1 pm CT (10 am PT) | Free Email [email protected] to register or for more info CHADDICK INSTITUTE FOR METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT AT DEPAUL UNIVERSITY CONTACT: JOSEPH SCHWIETERMAN, PH.D. | PHONE: 312.362.5732 | EMAIL: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The prognosis for the intercity bus industry remains uncertain due to the weakened financial condition of most scheduled operators and the unanswerable questions about the pace of a post-pandemic recovery. This year’s Outlook for the Intercity Bus Industry report draws attention to some of the industry’s changing fundamentals while also looking at notable developments anticipated this year and beyond. Our analysis evaluates the industry in six areas: i) The status of bus travel booking through January 2021; ii) Notable marketing and service developments of 2020; iii) The decline of the national bus network sold on greyhound.com that is relied upon by travelers on thousands of routes across the U.S. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Atlantic Maritimes Explorer by Rail | Montreal to Halifax

ATLANTIC MARITIMES EXPLORER BY RAIL | MONTREAL TO HALIFAX Atlantic Maritimes Explorer by Rail | Montreal to Halifax Eastern Canada Rail Vacation 8 Days / 7 Nights Montreal to Halifax Priced at USD $2,853 per person Prices are per person and include all taxes. Child age 10 yrs & under INTRODUCTION Experience the best of Montreal, Quebec City, Prince Edward Island in just over a week on this Atlantic Maritimes Explorer Train Trip. Discover Canada as you've never seen it before on a trip with VIA Rail through the Atlantic and Maritime provinces. Witness the dynamic landscapes change from cosmopolitan cities to quirky towns and enjoy your choice of tours in Montreal and Charlottetown. From wandering the local food market on foot to cruising for lobster by boat, each moment is as adventurous as the next. Itinerary at a Glance DAY 1 Arrive Montreal DAY 2 Montreal | Day Tour to Quebec City & Montmorency Falls DAY 3 Montreal | Freedom of Choice - Choose 1 of 3 Excursions Montreal to Charlottetown| VIA Rail Option 1. Montreal Half Day Sightseeing Tour Option 2 Walking Tour of Old Montreal Option 3 Beyond the Market Food Walking Tour DAY 4 Arrive Charlottetown | VIA Rail + Private Transfer DAY 5 Charlottetown | Island Drives & Anne of Green Gables Tour DAY 6 Charlottetown | Freedom of Choice - Choose 1 of 2 Excursions Option 1. Morning Lobster Cruise Option 2. Morning Charlottetown Highlights Tour Charlottetown to Halifax| Private Transfer Start planning your vacation in Canada by contacting our Canada specialists Call 1 800 217 0973 Monday - Friday 8am - 5pm Saturday 8.30am - 4pm Sunday 9am - 5:30pm (Pacific Standard Time) Email [email protected] Web canadabydesign.com Suite 1200, 675 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, BC, V6B 1N2, Canada 2021/06/14 Page 1 of 6 ATLANTIC MARITIMES EXPLORER BY RAIL | MONTREAL TO HALIFAX DAY 7 Halifax | Freedom of Choice - Choose 1 of 4 Excursions Option 1. -

Argentina Page 1 of 21

2008 Human Rights Reports: Argentina Page 1 of 21 2008 Human Rights Reports: Argentina BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2008 Country Report on Human Rights Practices February 25, 2009 Argentina is a federal constitutional republic with a population of approximately 40.1 million. In October 2007 the country held national presidential and legislative elections, and voters elected President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner in generally free and fair multiparty elections. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces. While the government generally respected the human rights of its citizens, the following human rights problems were reported: killings and use of excessive force by police or security forces; police and prison guard abuse and alleged torture of suspects and prisoners; overcrowded, substandard, and life-threatening prison and jail conditions; occasional arbitrary arrest and detention; prolonged pretrial detention; continued weak judicial independence; official corruption; domestic violence against women; trafficking in persons for sexual and labor exploitation, primarily within the country; and child labor. During the year, the government convicted several perpetrators of human rights abuses committed during the 1976 83 military dictatorship and continued trials that were suspended in 1989 90 when the government pardoned such perpetrators. RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life While the government or its agents did not commit any politically motivated killings, there were reports that police committed killings involving unwarranted or excessive force. Generally, officers accused of wrongdoing were administratively suspended until completion of an investigation. Authorities investigated and in some cases detained, prosecuted, and convicted the officers involved. -

2-Stroke Diesels on Britain's Rail Network

2-Stroke Diesels on Britain’s Rail Network Rodger Bradley Back in the 1950s, when British Railways was beginning work on the “Modernisation & Re-Equipment Programme” – effectively the changeover from steam to diesel and electric traction – the focus in the diesel world was mainly between high and medium speed engines. On top of which, there was a practical argument to support hydraulic versus electric transmission technology – for main line use, mechanical transmission was never a serious contender. The first main line diesels had appeared in the very last days before nationalisation, and the choice of prime mover was shaped to a great extent by the experience of private industry, and English Electric in particular. The railway workshops had little or no experience in The prototype main-line 2-stroke powered loco for the field, and the better known steam locomotive express passenger service on BR was never repeated. builders had had some less than successful attempts to Photo: Thomas's Pics CC BY 2.0, offer examples of the new diesel locomotives. That https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50662416 said, some of the smaller companies, who had worked with the railways pre-WW2 to supply small shunting Pilot Scheme & Modernisation In the first flush of enthusiasm for the new technology, British Railways announced three types of diesel locomotive to be trialled for main line use; diesel shunters had already been in use for a number of years. The shunting types were a mix of electric and mechanical transmission, paired with 4-stroke diesel engines, and not surprisingly the first main line designs included electric transmission and 4-stroke, medium speed engines. -

British Rail Maintenance Limited: Sale of Maintenance Depots

NATIONAL AUDIT OFFICE REPORT BY THE COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR GENERAL British Rail Maintenance Limited: Sale of Maintenance Depots ORDERED BY THE HOUSE OF COMMONS TO BE PRINTED 15 JULY 1996 LONDON:HMSO HC583 Session1995-96 Published19 July1996 29.70 BRITISHML WNTENWCE UMITED: S~E OF WNTEN~CE DEPOTS This report has been prepared under Section 6 of the National Audit Act, 1983 for presentation to the House of Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the Act. John Bourn National Audit Office Comptroller and Auditor General 8 Jtiy 1996 The Comptroller and Auditor General is the head of the National Audit Office employing some 750 staff. He, and the NAO,are totaUy independent of Government. He certifies the accounts of au Government departments and a wide range of other puhhc sector bodies; and he has statutory authori@ to report to Parliament on the economy, efficiency and effectiveness with which departments and other bodies have used their resources. BRITISH ML WINTENANCE LIMITED: SALE OF WNTENANCE DEPOTS Contents Page Introduction, summary and principal conclusions 1 Part 1: Privatisation as soou as possible h a competitive process 8 Timetable 8 Sales process 10 - Generating interest 10 - Maintaining price tension 10 - Information available to bidders 15 Part 2: Mtitatimg safety, reducing costs and improving efficiency 17 tithin a competitive entionment Safety 18 Restructuring 18 Intellectual property 19 WorMoad contracts 21 Bidding framework 21 Part 3: Obtaining the best possfile market price, taking account of 23 sale costs, habfities, staff iuterests Best possible market price 23 - Sale structure 23 - Valuation 32 - Property clawback 33 Selection of adtisers and costs 34 Indemnities and warranties 35 Staff interests 36 - Assistance to management buy-out teams 36 - Employees’ terms and conditions 36 Part 4 The classification of docmnents as “Not for NAO eyes” 38 Glossary 42 Appendices 1. -

The Nominees for Management Change

The Nominees for Management Change February 6, 2012 Pershing Square Capital Management, L.P. Disclaimer and Forward Looking Statements The information contained in this presentation (“Information”) is based on publicly available information about Canadian Pacific Railway Limited (“CP” or the “Company”), which has not been independently verified by Pershing Square Capital Management, L.P. ("Pershing Square"). Pershing Square recognizes that there may be confidential or otherwise non-public information in the possession of CP or others that could lead CP or others to disagree with Pershing Square’s conclusions. This presentation and the Information is not a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any securities. The analyses provided may include certain forward-looking statements, estimates and projections prepared with respect to, among other things, general economic and market conditions, changes in management, changes in Board composition, actions of CP and its subsidiaries or competitors, the ability to implement business strategies and plans and pursue business opportunities and conditions in the railway and transportation industries. Such forward-looking statements, estimates, and projections reflect various assumptions by Pershing Square concerning anticipated results that are inherently subject to significant uncertainties and contingencies and have been included solely for illustrative purposes, including those risks and uncertainties detailed in the continuous disclosure and other filings of CP and its subsidiary Canadian Pacific Railway Company with applicable Canadian securities commissions, copies of which are available on the System for Electronic Document Analysis and Retrieval ("SEDAR") at www.sedar.com. No representations, express or implied, are made as to the accuracy or completeness of such forward-looking statements, estimates or projections or with respect to any other materials herein. -

Delay Attribution Board Members and Representation

OFFICIAL Delay Attribution Board Members and Representation Franchised Passenger Class Band 1 DAB Representative Abellio ScotRail Veronica Bolton Avanti West Coast Trains Govia Thameslink Railway Franchised Passenger Class Band 2 Abellio East Anglia London & South Eastern Railway Phil Starling Arriva Rail North London North Eastern Railway First Great Western Ltd West Midlands Trains First MTR South Western Railway Franchised Passenger Class Band 3 Arriva Rail London Merseyrail Electrics Steve Longmore Chiltern Railway Company MTR Crossrail Cross Country Trains Serco Caledonian Sleepers East Midlands Trains Trenitalia C2C First TransPennine Express Keolis Amey Wales Non-Franchised Passenger Class Chinnor and Princes Risborough Nexus Tyne and Wear Jonathan Seagar East Coast Trains North Yorkshire Moors Railway Eurostar International Peak Rail Ffestiniog Railway Rail Express Systems Grand Central Railway Company Vintage Trains Heathrow Express West Coast Railway Company Hull Trains Company Yorkshire Supertram Locomotive Services Limited Non-Passenger Class companies - Band 1 DB Cargo Nigel Oatway Freightliner Non-Passenger Class companies - Band 2 Amey Rail Ltd GB Railfreight Mike Byrne Babcock Rail Harsco Rail Balfour Beatty Plant Rail Express Systems COLAS Rail Ltd Rail Operations Group Devon and Cornwall Railways Victa Railfreight Direct Rail Services VolkerRail Freightliner Heavy Haul Network Rail Alex Kenney Andrew Rowe Georgina Collinge Scott Provan Paul Harris Anna Langford Non-Voting Members Chairman: Richard Morris Secretary: Richard Ashley April 2021 . -

Railway-Age-Railroader-Of-The-Year

Railway Age’s Railroader of the Year Award The Railroader of the Year Award was started by Modern Railroads magazine in 1964 as the “Man of the Year” award. Railway Age acquired Modern Railroads in 1991 and has presented the award annually since 1992. Recipients under Modern Railroads 1964: D. W. Brosnan, Southern Railway System 1965: Stuart T. Saunders, Pennsylvania Railroad Co. 1966: Stuart T. Saunders, Pennsylvania Railroad Co. 1967: Louis W. Menk, Northern Pacific Railway 1968: William B. Johnson, Illinois Central Railroad 1969: John W. Barriger, Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad 1970: John S. Reed, Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway 1971: Jervis Langdon, Jr., Penn Central Transportation Co. 1972: Charles Luna, United Transportation Union 1973: James B. Germany, Southern Pacific Transportation Co. 1974: L. Stanley Crane, Southern Railway System 1975: Frank E. Barnett, Union Pacific Railroad 1976: Dr. William J. Harris, Jr., Association of American Railroads 1977: Edward G. Jordan, Conrail 1978: Robert M. Brown, Union Pacific Railroad 1979: Theodore C. Lutz, Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority 1980: John G. German, Missouri Pacific Railroad Co. 1981: Lawrence Cena, Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway 1982: A. Paul Funkhouser, Family Lines Rail System 1983: L. Stanley Crane, Conrail 1984: Hays T. Watkins, CSX Corp. 1985: John L. Cann, Canadian National 1986: Raymond C. Burton, Jr., Trailer Train Co. 1987: Willis B. Kyle, Kyle Railways 1988: Darius W. Gaskins, Jr., Burlington Northern 1989: W. Graham Claytor, Jr., Amtrak 1990: Arnold B. McKinnon, Norfolk Southern Corp. 1991: Mike Walsh, Union Pacific Railroad Recipients under Railway Age 1992: William H. Dempsey, Association of American Railroads 1993: Raymond C. -

September 28, 2007

Vol. 65, No. 39 Publishedished inin thethe interinterest of Division West, First Army and Fort Carson community Sept. 28, 2007 Visit the Fort Carson Web site at www.carson.army.mill Building the team 2nd BCT trains at AF Academy Story and photos by Cpl. Rodney Foliente 2nd Brigade Combat Team Public Affairs Office, 4th Infantry Division Soldiers from 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, conducted team-building training in Jacks Valley at the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs Sept. 7. Leaders from Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 2nd BCT, coor- dinated the event and opened the training up to their Soldiers and Soldiers from Company A, 204th Brigade Support Battalion, cooks from the Warhorse Dining Facility and medics from 1st Squadron, 10th Cavalry Regiment. “Overall, the Jacks Valley event was geared to provide a different training setting as well as to promote team spirit and team accomplishment,” said Sgt. 1st Class Erin Langes, training Soldiers from Company A, 204th Brigade Support Battalion, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, noncommissioned officer-in-charge, dig their way beneath an electrical fence at the Air Force Academy’s Leadership Reaction Course Sept. 7. HHC, 2nd BCT. He said Soldiers had a lot of fun and learned quite a bit. the day and saw the event as a “hugely their destinations. Soldiers had to accomplish their missions with limited “It was a chance for (Soldiers) to beneficial team-building exercise.” locate each point and then use that supplies, limited time and a whole get out, see a different part of Colorado Soldiers separated into squads, spot as reference to finding the next lot of teamwork.