Pre-Darwinian Thinking, the Voyage of the Beagle, and the Origin of Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

The First Geological Map of Patagonia

Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina 64 (1): 55 - 59 (2009) 55 THE FIRST GEOLOGICAL MAP OF PATAGONIA Eduardo O. ZAPPETTINI and José MENDÍA Servicio Geológico Minero Argentino (SEGEMAR) - Av. Julio A. Roca 651 (1322) Buenos Aires Emails: [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT This contribution analyses the first geological map of Patagonia drawn by Darwin around 1840, and colour-painted by Darwin himself. It had remained unpublished and only a small version in black and white had been printed before. The different units mapped by Darwin are analysed from a modern perspective, and his ability to show a synthesis of the complex geological structure of Patagonia is stressed. Keywords: Geological map, Patagonia, Patagonian Shingle, Darwin geologist. RESUMEN: El primer mapa geológico de la Patagonia. La presente contribución analiza el primer mapa geológico de la Patagonia reali- zado por Darwin cerca de 1840, pintado en colores por el mismo Darwin, que ha permanecido inédito y del que sólo se cono- cía una versión de tamaño reducido en blanco y negro. Se analizan las diferentes unidades mapeadas por Darwin desde una perspectiva actual, destacándose su habilidad para mostrar en esa síntesis la compleja estructura de la Patagonia. Palabras clave: Mapa geológico, Patagonia, Rodados Patagónicos, Darwin geólogo. DARWIN AND THE VOYAGE OF HMS BEAGLE At the time Charles Darwin set sail on board HMS Beagle on a journey that was to last two years and ended up lasting five, he was not more than an amateur naturalist that had quitted his medical courses and after that abandoned his in- tention of applying for a position in the Church of England, just to embrace the study of natural history. -

Staying Optimistic: the Trials and Tribulations of Leibnizian Optimism

Strickland, Lloyd 2019 Staying Optimistic: The Trials and Tribulations of Leibnizian Optimism. Journal of Modern Philosophy, 1(1): 3, pp. 1–21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.32881/jomp.3 RESEARCH Staying Optimistic: The Trials and Tribulations of Leibnizian Optimism Lloyd Strickland Manchester Metropolitan University, GB [email protected] The oft-told story of Leibniz’s doctrine of the best world, or optimism, is that it enjoyed a great deal of popularity in the eighteenth century until the massive earthquake that struck Lisbon on 1 November 1755 destroyed its support. Despite its long history, this story is nothing more than a commentators’ fiction that has become accepted wisdom not through sheer weight of evidence but through sheer frequency of repetition. In this paper we shall examine the reception of Leibniz’s doctrine of the best world in the eighteenth century in order to get a clearer understanding of what its fate really was. As we shall see, while Leibniz’s doctrine did win a good number of adherents in the 1720s and 1730s, especially in Germany, support for it had largely dried up by the mid-1740s; moreover, while opponents of Leibniz’s doctrine were few and far between in the 1710s and 1720s, they became increasing vocal in the 1730s and afterwards, between them producing an array of objections that served to make Leibnizian optimism both philosophically and theologically toxic years before the Lisbon earthquake struck. Keywords: Leibniz; Optimism; Best world; Lisbon earthquake; Evil; Wolff The oft-told story of Leibniz’s doctrine of the best world, or optimism, is that it enjoyed a great deal of popularity in the eighteenth century until the massive earthquake that struck Lisbon on 1 November 1755 destroyed its support. -

Pre-Darwinian Thinking, the Voyage of the Beagle, and the Origin of Species

Pre-Darwinian thinking, the voyage of the Beagle, and the Origin of Species How did life originate? What is responsible for the spectacular diversity that we see now? These are questions that have occupied numerous people for all of recorded history. Indeed, many independent mythological traditions have stories that discuss origins, and some of those are rather creative. For example, in Norse mythology the world was created out of the body of a frost giant! Some early attempts at scientific or philosophical discussion of life were apparent in Greece. For example, Thales (the earliest of the identified Greek philosophers) argued that everything stemmed ultimately from water. He therefore had a somewhat vague idea that descent with modification was possible, since things had to diversify from a common origin. Aristotle suggested that in every thing is a desire to move from lower to higher forms, and ultimately to the divine. Anaximander might have come closest to our modern conception: he proposed that humans originated from other animals, based on the observation that babies need care for such a long time that if the first humans had started like that, they would not have survived. Against this, however, is the observation that in nature, over human-scale observation times, very little seems to change about life as we can see it with our unaided eyes. Sure, the offspring of an individual animal aren’t identical to it, but puppies grow up to be dogs, not cats. Even animals that have very short generational times appear not to change sub- stantially: one fruit fly is as good as another. -

1 Charles Darwin's Notebooks from the Voyage of the `Beagle`. Transcribed, Edited and Introduced by Gordon Chancellor and John

Charles Darwin’s Notebooks from the Voyage of the `Beagle`. Transcribed, edited and introduced by Gordon Chancellor and John van Wythe. xxxiii + 615 pp. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2009. $ 150 (cloth). Until now, it has not been possible to read in book form the immediate notes that Darwin himself had written during his 1832-1836 voyage of H.M.S. Beagle. Darwin’s Beagle records comprised five different kinds: field notebooks, personal diary, geological and zoological diaries, and specimen catalogues. Unlike the many other documents that Darwin created during the voyage, the field notebooks are not confined to any one subject. They contain notes and observations on geology, zoology, botany, ecology, weather notes, barometer and thermometer readings, ethnography, archaeology, and linguistics as well as maps, drawings, financial records, shopping lists, reading notes, and personal entries. The editors described the notebooks as the most difficult and complex of all of Darwin’s manuscripts. They were for the most part written in pencil which was often faint or smeared. They were generally not written while sitting at a desk but held in one hand, on mule or horseback or on the deck of the Beagle. Furthermore the lines were very short and much was not written in complete sentences. Added to this, they were full of Darwin’s chaotic spelling of foreign names so the handwriting was sometimes very difficult to decipher. Alternative readings were often possible. Darwin did not number the pages of the notebooks, and often wrote in them at different times from opposite ends. Most of the notebook space was devoted to geological descriptions and drawings, a reflection of Darwin’s interest in the works of Charles Lyell and his previous fieldwork with Adam Sedgwick. -

Alexis Claude Clairaut

Alexis Claude Clairaut Born: 7 May 1713 in Paris, France Died: 17 May 1765 in Paris, France Alexis Clairaut's father, Jean-Baptiste Clairaut, taught mathematics in Paris and showed his quality by being elected to the Berlin Academy. Alexis's mother, Catherine Petit, had twenty children although only Alexis survived to adulthood. Jean-Baptiste Clairaut educated his son at home and set unbelievably high standards. Alexis used Euclid's Elements while learning to read and by the age of nine he had mastered the excellent mathematics textbook of Guisnée Application de l'algèbre à la géométrie which provided a good introduction to the differential and integral calculus as well as analytical geometry. In the following year, Clairaut went on to study de L'Hôpital's books, in particular his famous text Analyse des infiniment petits pour l'intelligence des lignes courbes. Few people have read their first paper to an academy at the age of 13, but this was the incredible achievement of Clairaut's in 1726 when he read his paper Quatre problèmes sur de nouvelles courbes to the Paris Academy. Although we have already noted that Clairaut was the only one of twenty children of his parents to reach adulthood, he did have a younger brother who, at the age of 14, read a mathematics paper to the Academy in 1730. This younger brother died in 1732 at the age of 16. Clairaut began to undertake research on double curvature curves which he completed in 1729. As a result of this work he was proposed for membership of the Paris Academy on 4 September 1729 but the king did not confirm his election until 1731. -

Resources on Charles Darwin, Evolution, and the Galapagos Islands: a Selected Bibliography

Library and Information Services Division Current References 2009-1 The Year of Darwin 2009 Discovering Darwin at NOAA Central Library: Resources on Charles Darwin, Evolution, and the Galapagos Islands: A Selected Bibliography Prepared by Anna Fiolek and Kathleen A. Kelly U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service National Oceanographic Data Center NOAA Central Library October 2009 http://www.lib.noaa.gov/researchtools/subjectguides/darwinbib.pdf Contents: Preface …………………………………………………………………. p. 3 Acknowledgment ………………………………………………………. p. 4 I. Darwin Chronology ………………………………………………….. p. 5-6 II. Monographic Publications By or About Charles Darwin ………... p. 7-13 in the NOAA Central Library Network Catalog (NOAALINC) III. Internet Resources Related to Charles Darwin ……. ……………. p. 14-17 And His Science (Including online images and videos) IV. Darwin Science-related Journals in the NOAA Libraries’………. p. 17-18 Network 2 Preface This Bibliography has been prepared to support NOAA Central Library (NCL) outreach activities during the Year of Darwin 2009, including a “Discovering Darwin at NOAA Central Library” Exhibit. The Year of Darwin 2009 has been observed worldwide by libraries, museums, academic institutions and scientific publishers, to honor the 150th anniversary of On the Origin of Species and the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birth. This Bibliography reflects the library’s unique print and online resources on Charles Darwin, Evolution, and the Galapagos Islands. It includes citations organized “by title” from NOAALINC, the library’s online catalog, and from the library’s historical collections. The data and listings are comprehensive from the 19th century to the present. The formats represented in this resource include printed monographs, serial publications, graphical materials, videos, online full-text documents, a related journal list, and Web resources. -

Charles Darwin and the Voyage of the Beagle

Charles Darwin And the Voyage of the Beagle Darwin interior proof.indd 1 10/8/19 12:19 PM To Ernie —R. A. Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHING COMPANY INC. 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2009 by Ruth Ashby Charles Darwin First trade paperback edition published in 2020 And the Voyage of the Beagle All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the pub- lisher. Book design and composition by Adela Pons Printed in October 2019 in the United States of America by RR Donnelley & Sons in Harrisonburg, Ruth Ashby Virginia 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 (hardcover) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 (trade paperback) HC ISBN: 978-1-56145-478-5 PB ISBN: 978-1-68263-127-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ashby, Ruth. Young Charles Darwin and the voyage of the Beagle / written by Ruth Ashby.—1st ed. p. cm. ISBN 13: 978-1-56145-478-5 / ISBN 10: 1-56145-478-8 1. Darwin, Charles, 1809-1882.—Juvenile literature. 2. Beagle Expedition (1831-1836)— Juvenile literature. 3. Naturalist—England—Biography—Juvenile literature. 4. Voyages around the world—Juvenile literature. I. Title. QH31.D2.A797 2009 910.4’1—dc22 2008036747 Darwin interior proof.indd 2-3 10/8/19 12:19 PM The Voyage of the Beagle Approximate Route, 1831–1836 B R I T I S H ISLANDS N WE EUROPE N O R T H S AMERICA ASIA NORTH CANARY ISLANDS ATLANTIC OCEAN PACIFIC CAPE VERDE ISLANDS OCEAN AFRICA INDIAN OCEAN GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS SOUTH To MADAGASCAR Tahiti AMERICA Bahia Lima Rio de Janeiro ST. -

VOYAGE of the BEAGLE (1831-1836 CE) Macquarie University Big History School: Core

READING 5.2.4 VOYAGE OF THE BEAGLE (1831-1836 CE) Macquarie University Big History School: Core Lexile® measure: 780L MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY BIG HISTORY SCHOOL: CORE - READING 5.2.4. VOYAGE OF THE BEAGLE: 1831-1836 CE - 780L 2 Below are the highlights of the 5-year voyage of the HMS Beagle. On this voyage, Charles Darwin formed his ideas around evolution by natural selection. VOYAGE OF THE BEAGLE (1831-1836 CE) By David Baker DECEMBER 27 1831: The HMS Beagle set sail from England on a journey around the world. The ship was under the command of Captain Fitzroy. Also on board was 22- year old Charles Darwin. Darwin is the ship’s naturalist. JANUARY 16 1832: The Beagle made landfall at St. Jago, Cape Verde Islands. The islands are just off the coast of West Africa. Darwin investigated the geology of the volcanic island. Darwin also collected many tropical animals. He was very interested in these creatures. He saw octopi that changed colours. There were also birds, which weren’t afraid of humans. Darwin also saw a layer of seashells in the rocky cliffs of the island. This implied that the Earth was slowly changing over time. New islands were being created and rising out of the sea. FEBRUARY 28 1832: The Beagle reached Brazil. Darwin saw slavery here, which disgusted him. The following year, the British Empire would abolish slavery. Darwin visited the lush forests and islands of Brazil. He collected more fascinating specimens. Darwin stayed for a time in Rio di Janeiro. Here, a deadly illness spread through the Beagle’s crew. -

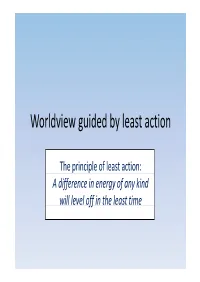

Worldview Guided by Least Action

Worldview guided by least action The principle of least action: A difference in energy of any kind will level off in the least time Pierre Louis Maupertuis (1698‐1759) Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646‐1716) The action The optimal among all conceivable changes in nature among all conceivable worlds is always at a minimum. is the actual. Maupertuis (1698‐1759) Leibniz (1646‐1716) Euler (1707‐1783)Lagrange (1736‐1813) Hamilton (1805‐1865) Open and path‐dependent processes Closed and path‐independent motions tt22 A 2Kdtpx d x U t Q dt A Ldt K U dt t tt11 The ppprinciple of least action A 2Kdtx U t Q dt t Fermat’s principle: Light takes the path of least time. Newton’s 2nd law of motion ddmdEdQp Favmdm; dt dt c22 v A bbbobymovesalong the path of resultan t force. The 2nd law of thermodynamics dQ dS;2;ln TS K S k P T B Heat flows along the path of least resistance. Any differentiable symmetry of the action of a physical system has a corresponding conservation law. Nature evolves from one state to another by consuming free energy in spontaneous symmetry breaking processes. Emmy Noether (1882‐1935) U(n) U(1) World in terms of actions The absolutely least action Neutrino SU(2) Photon U(1) World in terms of actions Electron and positron are least‐action paths wound from multiples of the most elementary action. Magnetic moment e e ; me 2 2 e Fine‐structure constant 4 oc World in terms of actions Proton (p) and neutron (n) are least‐action paths assembled from quarks and gluons wound from multiples of the most elementary action. -

A Crucible in Which to Put the Soul”: Keeping Body and Soul Together in the Moderate Enlightenment, 1740-1830

“A CRUCIBLE IN WHICH TO PUT THE SOUL”: KEEPING BODY AND SOUL TOGETHER IN THE MODERATE ENLIGHTENMENT, 1740-1830 DISSERTATION Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the doctor of philosophy degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University KARA ELIZABETH BARR, M.A. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY 2014 DISSERTATION COMMITTEE: Dale K. Van Kley, director Matthew D. Goldish, advisor Geoffrey Parker COPYRIGHT BY KARA ELIZABETH BARR 2014 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the relationship between Christianity and the Enlightenment in eighteenth-century Europe. Specifically, it explores how the Enlightenment produced the modern Western perception of the nature of the mind and its relationship to the body. While most traditional Enlightenment historiography argues that the movement was defined by radical, atheistic thinkers, like Diderot and Spinoza, who denied the existence of the traditional Christian immaterial and immortal soul, this project demonstrates that these extreme thinkers were actually a minority, confined largely to the intellectual fringes. By contrast, not only were many Enlightenment thinkers sincere Christians, but they were actually the most effective communicators of new ideas by showing how the Enlightenment supported, rather than attacked, traditional Christian beliefs. This moderate Enlightenment is responsible for developing Western ideas about how the mind and body are related, especially within the emerging fields of psychology and psychiatry in the mid-nineteenth century. This dissertation gains its focus through an examination of the work of two historiographically neglected enlightened thinkers—David Hartley in Britain, and the Abbé de Condillac in France. Both of them argued for the traditional Christian belief in an immortal soul, but used enlightened ideas to do so. -

Excerpts from Charles Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle Adapted with Permission From

Excerpts from Charles Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle Adapted with permission from www.literature.org Preface I have stated in the preface to the first Edition of this work, and in the Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle, that it was in consequence of a wish expressed by Captain Fitz Roy, of having some scientific person on board, accompanied by an offer from him of giving up part of his own accommodations, that I volunteered my services, which received, through the kindness of the hydrographer, Captain Beaufort, the sanction of the Lords of the Admiralty. As I feel that the opportunities which I enjoyed of studying the Natural History of the different countries we vis- ited, have been wholly due to Captain Fitz Roy, I hope I may here be permitted to repeat my expression of gratitude to him; and to add that, during the five years we were together, I received from him the most cordial friendship and steady assistance. Both to Captain Fitz Roy and to all the Officers of the Beagle.1 I shall ever feel most thankful for the undeviating kind- ness with which I was treated during our long voyage…. Devonport, England: 50°N, 4°W December, 27, 1831 After having been twice driven back by heavy southwestern gales, Her Majesty's ship Beagle, a ten-gun brig, under the command of Captain Fitz Roy, R.N., sailed from Devonport on the 27th of December, 1831. The object of the expedition was to complete the survey of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, commenced under Captain King in 1826 to 1830 -- to survey the shores of Chile, Peru, and of some islands in the Pacific -- and to carry a chain of chronometrical meas- urements round the World.