Control Marks on Hellenistic Royal Coinages: Use, and Evolution Toward Simplification ?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion

2019-3337-AJHIS-HIS 1 Alexander the Great and Hephaestion: 2 Censorship and Bisexual Erasure in Post-Macedonian 3 Society 4 5 6 Same-sex relations were common in ancient Greece and having both male and female 7 physical relationships was a cultural norm. However, Alexander the Great is almost 8 always portrayed in modern depictions as heterosexual, and the disappearance of his 9 life-partner Hephaestion is all but complete in ancient literature. Five full primary 10 source biographies of Alexander have survived from antiquity, making it possible to 11 observe the way scholars, popular writers and filmmakers from the Victorian era 12 forward have interpreted this evidence. This research borrows an approach from 13 gender studies, using the phenomenon of bisexual erasure to contribute a new 14 understanding for missing information regarding the relationship between Alexander 15 and his life-partner Hephaestion. In Greek and Macedonian society, pederasty was the 16 norm, and boys and men did not have relations with others of the same age because 17 there was almost always a financial and power difference. Hephaestion was taller and 18 more handsome than Alexander, so it might have appeared that he held the power in 19 their relationship. The hypothesis put forward here suggests that writers have erased 20 the sexual partnership between Alexander and Hephaestion because their relationship 21 did not fit the norm of acceptable pederasty as practiced in Greek and Macedonian 22 culture or was no longer socially acceptable in the Roman contexts of the ancient 23 historians. Ancient biographers may have conducted censorship to conceal any 24 implication of femininity or submissiveness in this relationship. -

The Coinage System of Cleopatra Vii, Marc Antony and Augustus in Cyprus

1 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS By Matthew Kreuzer 2 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS By Matthew Kreuzer Second Edition Springfield, Mass. Copyright Matthew Kreuzer 2000-2009. 3 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS Contents Summary 5 Historical Background 9 Coins Circulating in Cleopatra’s Cyprus 51-30 BC 10 What Were the Denominations in Cleopatra’s Cyprus? 12 The Tetradrachm 13 The Drachm 28 The Full-Unit 29 The Half-Unit 35 The Quarter-Unit 39 The Eighth-Unit 41 The Tiny Sixteenth-Unit 45 Other Small Late Ptolemaic Bronzes 48 Archeological Context – A Late Ptolemaic Bronze Mint 50 Making Small Change 53 Relationship Between the Denominations 55 Circulating Earlier Ptolemaic and Foreign Coinage 56 Cypriot Bronze of Cleopatra, After Actium 58 Silver denarii of Marc Antony, 37-30 BC 61 Cypriot Coinage Under Augustus, 30-22 BC 69 Cypriot Bronze of Augustus, CA coinage 70 Non-Export Obols and Quadrans 75 Silver Quinarii and Denarii of Augustus, 28-22 BC 78 Cyprus as a Senatorial Province under Augustus, 22 BC to 14 AD 87 Cypriot Coinage under Tiberius and Later, After 14 AD 92 Table of Suggested Attribution Changes 102 Appendix I - Analysis of Declining Obol Weight Standard 121 Appendix II - Octavia or Cleopatra? Credits and Bibliography 139 4 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS "If the nose of Cleopatra had been a little shorter, the whole face of the world would have been changed." Blaise Pascal 5 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS Summary During the late reign of Cleopatra VII a cornucopia of coinage circulated in Cyprus. -

Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics Title The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xh6g8nn Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics, 2(1) ISSN 2373-7115 Author Gavryushkina, Marina Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gavryushkina 1 The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013 Abstract: Hellenistic coinage is a popular topic in art historical research as it is an invaluable resource of information about the political relationship between Greek rulers and their subjects. However, most scholars have focused on the wealthier and more famous dynasties of the Ptolemies and the Seleucids. Thus, there have been considerably fewer studies done on the artistic styles of the coins of the smaller outlying Hellenistic kingdoms. This paper analyzes the numismatic portraiture of the kings of Pontus, a peripheral kingdom located in northern Anatolia along the shores of the Black Sea. In order to evaluate the degree of similarity or difference in the Pontic kings’ modes of representation in relation to the traditional royal Hellenistic style, their coinage is compared to the numismatic depictions of Alexander the Great of Macedon. A careful art historical analysis reveals that Pontic portrait styles correlate with the individual political motivations and historical circumstances of each king. Pontic rulers actively choose to diverge from or emulate the royal Hellenistic portrait style with the intention of either gaining support from their Anatolian and Persian subjects or being accepted as legitimate Greek sovereigns within the context of international politics. -

Seleucid Coinage and the Legend of the Horned Bucephalas

Seleucid coinage and the legend of the horned Bucephalas Autor(en): Miller, Richard P. / Walters, Kenneth R. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische numismatische Rundschau = Revue suisse de numismatique = Rivista svizzera di numismatica Band (Jahr): 83 (2004) PDF erstellt am: 04.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-175883 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch RICHARD P. MILLER AND KENNETH R.WALTERS SELEUCID COINAGE AND THE LEGEND OF THE HORNED BUCEPHALAS* Plate 8 [21] Balaxian est provincia quedam, gentes cuius Macometi legem observant et per se loquelam habent. Magnum quidem regnum est. Per successionem hereditariam regitur, quae progenies a rege Alexandra descendit et a filia regis Darii Magni Persarum... -

Keltoi and Hellenes: a Study of the Celts in the Hellenistic World

KELTOI AND THE HELLENES A STUDY OF THE CELTS IN THE HELLENISTIC WoRU) PATRICK EGAN In the third century B.C. a large body ofCeltic tribes thrust themselves violently into the turbulent world of the Diadochoi,’ immediately instilling fear, engendering anger and finally, commanding respect from the peoples with whom they came into contact. Their warlike nature, extreme hubris and vigorous energy resembled Greece’s own Homeric past, but represented a culture, language and way of life totally alien to that of the Greeks and Macedonians in this period. In the years that followed, the Celts would go on to ravage Macedonia, sack Delphi, settle their own “kingdom” and ifil the ranks of the Successors’ armies. They would leave indelible marks on the Hellenistic World, first as plundering barbaroi and finally, as adapted, integral elements and members ofthe greatermulti-ethnic society that was taking shape around them. This paper will explore the roles played by the Celts by examining their infamous incursions into Macedonia and Greece, their phase of settlement and occupation ofwhat was to be called Galatia, their role as mercenaries, and finally their transition and adaptation, most noticeably on the individual level, to the demands of the world around them. This paper will also seek to challenge some of the traditionally hostile views held by Greek historians regarding the role, achievements, and the place the Celts occupied as members, not simply predators, of the Hellenistic World.2 19 THE DAWN OF THE CELTS IN THE HELLENISTIC WORLD The Celts were not unknown to all Greeks in the years preceding the Deiphic incursion of February, 279. -

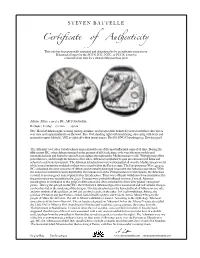

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Two Late Fifth Century B.C. Hoards from South Italy

Two late fifth century B.C. Hoards from south Italy Autor(en): Kraay, Colin M. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische numismatische Rundschau = Revue suisse de numismatique = Rivista svizzera di numismatica Band (Jahr): 49 (1970) PDF erstellt am: 08.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-173963 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch COLIN M. KRAAY TWO LATE FIFTH CENTURY B.C. HOARDS FROM SOUTH ITALY Although the first of the hoards here described was found long ago and dispersed immediately after discovery, it still seems possible to extract from the surviving account more detailed information about its contents than has yet been done. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

A Literary Sources

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Index More Information Index A Literary sources Livy XXVI.24.7–15: 77 (a); XXIX.12.11–16: 80; XXXI.44.2–9: 11 Aeschines III.132–4: 82; XXXIII.38: 195; XXXVII.40–1: Appian, Syrian Wars 52–5, 57–8, 62–3: 203; XXXVIII.34: 87; 57 XXXIX.24.1–4: 89; XLI.20: 209 (b); ‘Aristeas to Philocrates’ I.9–11 and XLII.29–30.7: 92; XLII.51: 94; 261 V.35–40: XLV.29.3–30 and 32.1–7: 96 15 [Aristotle] Oeconomica II.2.33: I Maccabees 1.1–9: 24; 1.10–25 and 5 7 Arrian, Alexander I.17: ; II.14: ; 41–56: 217; 15.1–9: 221 8 9 III.1.5–2.2: (a); III.3–4: ; II Maccabees 3.1–3: 216 12 13 IV.10.5–12.5: ; V.28–29.1: ; Memnon, FGrH 434 F 11 §§5.7–11: 159 14 20 V1.27.3–5: ; VII.1.1–4: ; Menander, The Sicyonian lines 3–15: 104 17 18 VII.4.4–5: ; VII.8–9 and 11: Menecles of Barca FGrHist 270F9:322 26 Arrian, FGrH 156 F 1, §§1–8: (a); F 9, Pausanias I.7: 254; I.9.4: 254; I.9.5–10: 30 §§34–8: 56; I.25.3–6: 28; VII.16.7–17.1: Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae V.201b–f, 100 258 43 202f–203e: ; VI.253b–f: Plutarch, Agis 5–6.1 and 7.5–8: 69 23 Augustine, City of God 4.4: Alexander 10.6–11: 3 (a); 15: 4 (a); Demetrius of Phalerum, FGrH 228 F 39: 26.3–10: 8 (b); 68.3: cf. -

Hasmonean” Family Tree

THE “HASMONEAN” FAMILY TREE Hasmoneus │ Simeon │ John │ Mattathias ┌──────────────┬─────────────────────┼─────────────────┬─────────┐ John Simon Judas Maccabee Eleazar Jonathan Murdered: Murdered: KIA: KIA: Murdered: 160/159 BC 134 BC 160 BC 162 BC 143 BC ┌────────┬────┴────┐ Judas John Hyrcanus Murdered: Murdered: Died: 134 BC 135 BC 104 BC ├──────────────────────┬─────────────┐ Aristobulus ═ Salome Alexander Antigonus Alexander ═══════ Salome Alexander Declared Himself “King”: Murdered: Declared “King”: Declared “Regent”: 104 BC 103 BC 103 BC 76 BC Died: Died: 103 BC 76 BC ┌──────┴──────┐ Hyrcanus II Aristobulus II Declared High Priest: 76 BC 1 THE “HASMONEAN” DYNASTY OF SIMON THE HIGH PRIEST 142 BC Simon, the last of the sons of Mattathias, was declared High Priest & “Ethnarch” (ruler of one’s own ethnic group) of the Jews by Demetrius II, King of the Seleucid Empire. 138 BC After Demetrius II was captured by the Parthians, his brother, Antiochus VII, affirmed Simon’s High Priesthood & requested assistance in dealing with Trypho, a usurper of the Seleucid throne. “King Antiochus to Simon the high priest and ethnarch and to the nation of the Jews, greetings. “Whereas certain scoundrels have gained control of the kingdom of our ancestors, and I intend to lay claim to the kingdom so that I may restore it as it formerly was, and have recruited a host of mercenary troops and have equipped warships, and intend to make a landing in the country so that I may proceed against those who have destroyed our country and those who have devastated many cities in my kingdom, now therefore I confirm to you all the tax remissions that the kings before me have granted you, and a release from all the other payments from which they have released you. -

Royal Correspondence in the Hellenistic Period : a Study in Greek

TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE vii LIST OF WORKS CITED BY ABBREVIATED TITLE ... xvü COMPARATIVE TABLE OF EDITIONS xxix INTRODUCTION. I. THE USE OF LETTERS IN HELLENISTIC DIPLO- MACY XXXVÜ IL COMPOSITION AND STYLE OF THE LETTERS. xK III. THE LANGUAGE OF THE LETTERS. 1. PALEOGRAPHY. A. The Alphabet xlvi B. Arrangement of the Text liii C. Punctuation and Diacritical Marks liii D. Abbreviation liv E. Syllable Division Uv F. Engravers* Mistakes Iv 2. SOUNDS. A. Vowels. a) Dialectic Differences Iv b) Elidon lix e) Crasis lix B. Consonants. a) Dialectic Differences Ix b) Assimilation Ixii c) Nu Movable Ixiii 3. INFLECTIONS. A. Declension Ixiv B. Conjugation ^ ......... Ixvi OONIENIS 4. SYNTAX. A. Case 'IzñS B. Number hâ C. PZOOOUDS ............. w....... 3ñK D. Tlie Aitide ; In £. NnmeralB btx F. TheVob. •) Tense kz b) Fbàtt Moodt hzi cj Voice im 4) Tlie Infinitive faczñ $) The Particqde bom G. Pri^xisitioiis. èssô ., :...., , • hou fee bimi lEopd , .-...., boEm OUI ,...,.,,...,....,.,,,., bcñv feuS boiv peni bodv ÜW bsv Ar . ', bŒv dç Ixm JfQoç .-.•.... bacvñ wnd ,,., .,...-... boLviH bó . .*. •. .. .. .. .,,•-.. .. , bcDZ met . , . lux MQ hopá BUÇ ....,.,,.....,.,,.,,..,, booo fannrao ...,.......,....,,,,,, |ir^^ H. Conjunctions. Iwo . fasxñ 5AOç -...•......-.«,....... !••••" Antitheses ....1....... I^niîî I. Paurtídes .,........,,...•,,,., 1TíTI?IFH Negatives .-.., , buuîv ¿ Word Order boaav 5. VOCABULARY . bow 6. SUMMARY. A. &OQie Elenients ...........:,,..,' xcm CONTENTS îtiîî B Elements Derived from the Old Dialects, 1. ^onic xcvii 2. Attic .... i . xcviii 3. AeoUc or Doric xcviU C. Barbarisms xcvîii TEXTS.1 1. Letter of Anfígónus to Scepsis. 311 B. C 3 2. Letter of Antigonus to Eresus. About 306 B. C 12 3/4. Letters of Antigonus to Teos. -

Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult

ΑΡΣΙΝΟΗ ΕΥΠΛΟΙΑ Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult Carlos Francis Robinson Bachelor of Arts (Hons. 1) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 Historical and Philosophical Inquiry Abstract Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult By the early Hellenistic period a trend was emerging in which royal women were deified as Aphrodite. In a unique innovation, Queen Arsinoë II of Egypt (c. 316 – 270 BC) was deified as the maritime Aphrodite, and was associated with the cult titles Euploia, Akraia, and Galenaië. It was the important study of Robert (1966) which identified that the poets Posidippus and Callimachus were honouring Arsinoë II as the maritime Aphrodite. This thesis examines how this new third-century BC cult of ‘Arsinoë Aphrodite’ adopted aspects of Greek cults of the maritime Aphrodite, creating a new derivative cult. The main historical sources for this cult are the epigrams of Posidippus and Callimachus, including a relatively new epigram (Posidippus AB 39) published in 2001. This thesis demonstrates that the new cult of Arsinoë Aphrodite utilised existing traditions, such as: Aphrodite’s role as patron of fleets, the practice of dedications to Aphrodite by admirals, the use of invocations before sailing, and the practice of marine dedications such as shells. In this way the Ptolemies incorporated existing religious traditions into a new form of ruler cult. This study is the first attempt to trace the direct relationship between Ptolemaic ruler cult and existing traditions of the maritime Aphrodite, and deepens our understanding of the strategies of ruler cult adopted in the early Hellenistic period.