I Gede Wahyu Wicaksana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AKAL DAN WAHYU DALAM PEMIKIRAN M. QURAISH SHIHAB Yuhaswita*

AKAL DAN WAHYU DALAM PEMIKIRAN M. QURAISH SHIHAB Yuhaswita* Abstract Reason according to M. Quraish Shihab sense is the thinking power contained in man and is a manipation of the human soul. Reason is not understood materially but reason is understood in the abstract so that sense is interpreted a thinking power contained in the human soul, with this power man is able to gain knowledge and be able to distinguish between good and evil. Revelation according to M. Quraish Shihab, is the delivery of God’s Word to His chosen people to be passed on to human beings to be the guidance of life. God’s revelation contains issues of aqidah, law, morals, and history. Furthermore, M. Quraish Shihab reveals that human reason is very limited in understanding the content of Allah’s revelation, because in Allah’s revelation there are things unseen like doomsday problems, death and so forth. The function of revelation provides information to the sense that God is not only reachable by reason but also heart. Kata Kunci: problematika, nikah siri, rumah tangga Pendahuluan M. Quraish Shihab adalah seorang yang tidak baik untuk dikerjakan oleh ulama dan juga pemikir dalam ilmu al Qur’an manusia. dan tafsir, M. Quraish Shihab termasuk Ketika M. Quraish Shihab seorang pemikir yang aktif melahirkan karya- membahas tentang wahyu, sebagai seorang karya yang bernuansa religious, disamping itu mufasir tentunya tidak sembarangan M. Quraish Shihab juga aktif berkarya di memberikan menafsirkan ayat-ayat al berbagai media massa baik media cetak Qur’an yang dibacanya, Wahyu adalah kalam maupun elektronik, M.Quraish Shihab sering Allah yang berisikan anjuran dan larangan tampil di televise Metro TV memberikan yang harus dipatuhi oleh hamba-hamba-Nya. -

Correlation Between Career Ladder, Continuing Professional Development and Nurse Satisfaction: a Case Study in Indonesia

International Journal of Caring Sciences September-December 2017 Volume 10 | Issue 3| Page 1490 Original Article Correlation between Career Ladder, Continuing Professional Development and Nurse Satisfaction: A Case Study in Indonesia Rr. Tutik Sri Hariyati, Dr.,SKp, MARS Associate Professor, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia Kumiko Igarashi, RN, PhD Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Government of Japan, Japan Tokyo, Kasumigaseki, Chiyodaka, Japan Yuma Fujinami, Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) Tokyo, Japan Dr.F.Sri Susilaningsih, SKp Pajajaran University, Faculty of Nursing Bandung, West Java, Indonesia Dr. Prayenti, SKp., M.Kes Politeknik Kesehatan Kemenkes Jakarta III, Ministry of health Jakarta, Indonesia Corespondence: Rr. Tutik Sri Hariyati, Dr.,SKp, MARS, Associate Professor, Faculty of Nursing, Kampus Fakultas Ilmu Keperawatan, Universitas Indonesia, Depok 16424 Indonesia E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract In general, the majority of health professions in hospitals are occupied by nurses; thus, nurses play crucial roles in health services and hold the responsibility of delivering a care to patients professionally and safely. Therefore, the ability to prevent and minimizing errors they may make also is imperative. The purpose of this research is to identify nurse’s perception of the Career Ladder System (CLS), Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for nurses and correlation between perception and nurse’s job satisfaction. A descriptive, non-experimental survey method was used for this study. Survey was conducted at eight hospitals. The answerers were selected by proportional sampling and sample size was 1487 nurses. Data was analyzed by using Descriptive and Correlation Spearmen and The Mines Job Satisfaction Scale (MNPJSS). -

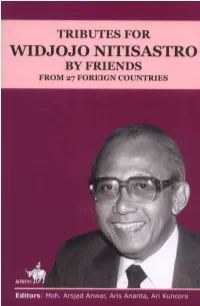

Tributes1.Pdf

Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, January 2007 Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Published by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, January 2007 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70007006 Editor: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editor: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. -

Failure of Bilateral Diplomacy on Irian Barat (Papua) Dispute (1950-1954)

FAILURE OF BILATERAL DIPLOMACY ON IRIAN BARAT (PAPUA) DISPUTE (1950-1954) Siswanto Center for Political Studies, The Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Jakarta E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Fundamentally, Irian Barat (Papua) dispute between The Netherlands –Indonesia was a territorial conflict or an overlapping claim. The Netherlands as the former colonialist did not want to leave Irian Barat (Papua) or remained still in the region, meanwhile Indonesia as the former colony denied the Netherlands status quo policy in Irian Barat (Papua). Potential dispute of the Irian Barat (Papua) was begun in the Round Table Conference (RTC) 1949. There was a point of agreement in RTC which regulates status quo on Irian Barat (Papua) and it was approved by Head of Indonesia Delegation, Mohammad Hatta and Van Maarseven, Head of the Netherlands Delegation. As a mandate of the RTC in 1950s there was a diplomacy on Irian Barat (Papua) in Jakarta and Den Haag. Upon the diplomacy, there were two negotiations held by diplomats of both countries, yet it never reached a result. As a consequence, in 1954 Indonesia Government decided to stop the negotiation and searched for other ways as a solution for the dispute. At the present time, Jakarta-Papua relationship is relatively better and it is based on a special autonomy, which gives great authority to the Local Government of Papua. Keywords: the Netherlands, Indonesia, status quo, Irian Barat (Papua), diplomacy Abstrak Pada dasarnya perselisihan Irian Barat (Papua) antara Belanda –Indonesia adalah konflik teritorial atau tumpang tindih klaim. Belanda sebagai mantan penjajah tidak ingin meninggalkan Irian Barat (Papua) atau masih ingin menduduki kawasan itu, di sisi lain Indonesia sebagai bekas bangsa terjajah menolak kebijakan status quo Belanda di Irian Barat (Papua). -

Management of Communism Issues in the Soekarno Era (1959-1966)

57-67REVIEW OF INTERNATIONAL GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION ISSN: 2146-0353 ● © RIGEO ● 11(5), SPRING, 2021 www.rigeo.org Research Article Management of Communism Issues in The Soekarno Era (1959-1966) Abie Besman1 Dian Wardiana Sjuchro2 Faculty of Communication Science, Universitas Faculty of Communication Science, Universitas Padjadjaran Padjadjaran [email protected] Abstract The focus of this research is on the handling of the problem of communism in the Nasakom ideology through the policies and patterns of political communication of President Soekarno's government. The Nasakom ideology was used by the Soekarno government since the Presidential Decree in 1959. Soekarno's middle way solution to stop the chaos of the liberal democracy period opened up new conflicts and feuds between the PKI and the Indonesian National Army. The compromise management style is used to reduce conflicts between interests. The method used in this research is the historical method. The results showed that the approach adopted by President Soekarno failed. Soekarno tried to unite all the ideologies that developed at that time, but did not take into account the political competition between factions. This conflict even culminated in the events of September 30 and the emergence of a new order. This research is part of a broader study to examine the management of the issue of communism in each political regime in Indonesia. Keywords Nasakom; Soekarno; Issue Management; Communism; Literature Study To cite this article: Besman, A.; and Sj uchro, D, W. (2021) Management of Communism Issues in The Soekarno Era (1959-1966). Review of International Geographical Education (RIGEO), 11(5), 48-56. -

Female Circumcision: Between Myth and Legitimate Doctrinal Islam

Jurnal Syariah, Jil. 18, Bil. 1 (2010) 229-246 Shariah Journal, Vol. 18, No. 1 (2010) 229-246 FEMALE CIRCUMCISION: BETWEEN MYTH AND LEGITIMATE DOCTRINAL ISLAM Mesraini* ABSTRACT Circumcision on female has sociologically been practiced since long time ago. It is believed to be done for certain purposes. One of the intentions is that it is as an evidence of sacrifice of the circumcised person to get close to God. In the last decades, the demand for ignoring this practice on female by various circles often springs. Reason being is that the practice is accused of inflicting female herself. Moreover, it is regarded as a practice that destroys the rights of female reproduction and that of female sexual enjoyment and satisfaction. Commonly, female circumcision is done by cutting clitoris and throwing the minor and major labia. This practice of circumcision continues based on the myths that spread so commonly among people. This article aims to conduct a research on female circumcision in the perspective of Islamic law. According to Islamic doctrine, female circumcision is legal by Islamic law. By adopting the methodology of syar‘a man qablana (the law before us) and theory of maqasid al-syari‘ah (the purposes of Islamic law) and some other legitimate Quranic verses, circumcision becomes an important practice. Again, the famous female circumcision practice is evidently not parallel with the way recommended by Islam. Keywords: circumcision, female, Islamic law, tradition * Lecturer, State Islamic University Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, mesraini@yahoo. com 229 Jurnal Syariah, Jil. 18, Bil. 1 (2010) 229-246 INTRODUCTION Circumcision practice is a tradition, known worldwide and admitted by monotheistic religions members especially the Jewish, Muslim and some of the Christians. -

Indonesia Steps up Global Health Diplomacy

Indonesia Steps Up Global Health Diplomacy Bolsters Role in Addressing International Medical Challenges AUTHOR JULY 2013 Murray Hiebert A Report of the CSIS Global Health Policy Center Indonesia Steps Up Global Health Diplomacy Bolsters Role in Addressing International Medical Challenges Murray Hiebert July 2013 About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars are developing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full- time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. Former U.S. senator Sam Nunn has chaired the CSIS Board of Trustees since 1999. Former deputy secretary of defense John J. Hamre became the Center’s president and chief executive officer in April 2000. CSIS does not take specific policy positions; accordingly, all views expressed herein should be understood to be solely those of the author(s). -

INDONESIA's FOREIGN POLICY and BANTAN NUGROHO Dalhousie

INDONESIA'S FOREIGN POLICY AND ASEAN BANTAN NUGROHO Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia September, 1996 O Copyright by Bantan Nugroho, 1996 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibbgraphic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Lïbraiy of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous papa or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fïim, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substautid extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. DEDICATION To my beloved Parents, my dear fie, Amiza, and my Son, Panji Bharata, who came into this world in the winter of '96. They have been my source of strength ail through the year of my studies. May aii this intellectual experience have meaning for hem in the friture. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents v List of Illustrations vi Abstract vii List of Abbreviations viii Acknowledgments xi Chapter One : Introduction Chapter Two : indonesian Foreign Policy A. -

Adam Malik (Deppen) in MEMORIAM: ADAM MALIK A917-1984)

144 Adam Malik (Deppen) IN MEMORIAM: ADAM MALIK a917-1984) Ruth T. McVey The great survivor is dead. Though Adam Malik was by no means the only politician to hold high office under both Guided Democracy and the New Order, he was by far the most distinguished and successful. Others were political hacks with no true political coloring, or representatives of specialized con stituencies not involved directly in the conflict between Sukarno and the army; but Malik had been a central figure in the formulation of Guided Democracy and a close counsellor of Sukarno. Moreover, having chosen against that leader in the crisis following the coup of October 1965, he was not thereby completely discredited in the eyes of his former colleagues. For many of his old leftist associates he remained a patron: a leader who would still receive and could occasionally aid them, who could still speak their language, if only in private, and who still—in spite of his evident wealth, Western admirers, and service to a counter-revolutionary regime—seemed to embody what remained of the Generation of ’45, the fading memories of a radical and optimistic youth. To survive so successfully, a man must either be most simple and consistent, or quite the opposite. No one could accuse Adam Malik of transparency, yet there was a consistency about the image he cultivated. From early youth he appeared as a radical nationalist, a man of the left; and however unsympathetic the regime to that viewpoint he never allowed the pursuit of ambition completely to cloud that picture. -

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: a Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: John O. Haley, Chair Michael E. Townsend Beth E. Rivin Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Law © Copyright 2015 Yu Un Oppusunggu ii University of Washington Abstract Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor John O. Haley School of Law A sweeping proviso that protects basic or fundamental interests of a legal system is known in various names – ordre public, public policy, public order, government’s interest or Vorbehaltklausel. This study focuses on the concept of Indonesian public order in private international law. It argues that Indonesia has extraordinary layers of pluralism with respect to its people, statehood and law. Indonesian history is filled with the pursuit of nationhood while protecting diversity. The legal system has been the unifying instrument for the nation. However the selected cases on public order show that the legal system still lacks in coherence. Indonesian courts have treated public order argument inconsistently. A prima facie observation may find Indonesian public order unintelligible, and the courts have gained notoriety for it. This study proposes a different perspective. It sees public order in light of Indonesia’s legal pluralism and the stages of legal development. -

Pekerja Migran Indonesia Opini

Daftar Isi EDISI NO.11/TH.XII/NOVEMBER 2018 39 SELINGAN 78 Profil Taman Makam Pahlawan Agun Gunandjar 10 BERITA UTAMA Pengantar Redaksi ...................................................... 04 Pekerja Migran Indonesia Opini ................................................................................... 06 Persoalan pekerja migran sesungguhnya adalah persoalan Kolom ................................................................................... 08 serius. Banyaknya persoalan yang dihadapi pekerja migran Indonesia menunjukkan ketidakseriusan dan ketidakmampuan Bicara Buku ...................................................................... 38 negara memberikan perlindungan kepada pekerja migran. Aspirasi Masyarakat ..................................................... 47 Debat Majelis ............................................................... 48 Varia MPR ......................................................................... 71 Wawancara ..................................................... 72 Figur .................................................................................... 74 Ragam ................................................................................ 76 Catatan Tepi .................................................................... 82 18 Nasional Press Gathering Wartawan Parlemen: Kita Perlu Demokrasi Ala Indonesia COVER 54 Sosialisasi Zulkifli Hasan : Berpesan Agar Tetap Menjaga Persatuan Edisi No.11/TH.XII/November 2018 Kreatif: Jonni Yasrul - Foto: Istimewa EDISI NO.11/TH.XII/NOVEMBER 2018 3 -

Oleh: FLORENTINUS RECKYADO

PRINSIP-PRINSIP KEMANUSIAAN RERUM NOVARUM DALAM PERPEKTIF PANCASILA SKRIPSI SARJANA STRATA SATU (S-1) Oleh: FLORENTINUS RECKYADO 142805 SEKOLAH TINGGI KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN WIDYA YUWANA MADIUN 2021 PRINSIP-PRINSIP KEMANUSIAAN RERUM NOVARUM DALAM PERPEKTIF PANCASILA SKRIPSI Diajukan kepada Sekolah Tinggi Keguruan Dan Ilmu Pendidikan Widya Yuwana Madiun untuk memenuhi sebagian persyaratan memperoleh gelar Sarjana Strata Satu (S-1) Oleh: FLORENTINUS RECKYADO 142805 SEKOLAH TINGGI KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN WIDYA YUWANA MADIUN 2021 PERNYATAAN TIDAK PLAGIAT Saya yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini: Nama : Florentinus ReckYado NPM :142805 Programstudi : Ilmu Pendidikan Teologi Jenjang Studi : Strata Satu Judul skripsi : Prinsip-Prirsip Kemanusiaan Rerum Novarum ' Dalam Perpektif Pancasila Dengan ini saya menyatakan bahwa: 1. Skripsi ini adalah mumi merupakan gagasan, mmusan dan penelitian saya sendiri tanpa ada bantuan pihak lain kecuali bimbingan dan arahan dosen pembimbing. 2. Skripsi ini belum pemah diajukan untuk mendapat gelat akademik apapun di STKIP Widya Yuwana Madiun maupun di perguruan tinggi lain- 3. Dalam skripsi ini tidak terdapat karya atau pendapat yang ditulis atau dipublikasikan orang lain kecuali secara tertulis dengan mencantumkan sebagai acuan dalam naskah dengan menyebutkan nama pengamng dan mencantumkan dalam daftar pust*a. Demikianlah pemyataan ini saya buat dengan sesungguhnya dan apabila dikemudian hari terbukti pemyataan ini tidak benar, maka saya bersedia menerima sanksi akademik berupa pencbutan gelar yang telah diberikan melalui karya tulis ini se(a sanksi lainnya sesuai dengan norma yang berlaku di perguruan tinggi ini. Madi !.fl... hs :!.t.1:'. t 74Y\ lvtETERAl TEMPEL DAJX198738966 Florentinus Reckyado 142805 HALAMAN PERSETUJUAN Skripsi dengan judul "Prinsip-Prinsip Kemanusiaan Rerum Novarum Dalam Perpektif Pancasila", yang ditulis oleh Florentinus Reckyado telah diterima dan disetujui untuk diqji pada tanggal tA 3u\i eo3\ Oleh: Pembimbing Dr.