Oral History of Joanna Hoffman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Filling the Shoes the Organization Considers

TODAY ONLINE >> Lariat Letters: Send us responses to articles, columns and editorials at [email protected]. Baylor FRIENDS FOR LIFE pg. 3 LariatWE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE OCTOBER 22, 2015 THURSDAY BAYLORLARIAT.COM BAYLOR BLESSING SUSTAINABILITY Baylor becomes even greener RACHEL LELAND Reporter Baylor proved that it was green in more than one way when the university was recognized by e Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education for outstanding performance in sustainability. e Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education presented Baylor with the Silver award, the second highest award. Baylor was also recognized as the top performer Dane Chronister | News Editor in the categories of Coordination, DREAM COME TRUE Midway High School sophomore Kade Perry got a chance to not only meet with one of his mascot heroes, but he got to be Planning,and Governance and Bruiser. Perry walked around campus on Wednesday and greeted students with a Sic ‘em and a hug. Diversity and A ordability. Although Baylor had been awarded the Bronze award by e Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education in 2012, this was the rst year Baylor quali ed as a top performer in any of the 17 categories Filling the shoes the organization considers. “We’ve never been recognized at this higher level,” said director of sustainability, Smith Getterman. Young man from Midway gets the opportunity of a lifetime Getterman along with the Baylor Student Sustainability Advisory Board were instrumental in gathering the DANE CHRONISTER Panther. epitome of what we are supposed to be,” said data that was to be submitted to e News Editor In his journey in becoming the mascot, Wesley Perry. -

Automatic Graph Drawing Lecture 15 Early HCI @Apple/Xerox

Inf-GraphDraw: Automatic Graph Drawing Lecture 15 Early HCI @Apple/Xerox Reinhard von Hanxleden [email protected] 1 [Wikipedia] • One of the first highly successful mass- produced microcomputer products • 5–6 millions produced from 1977 to 1993 • Designed to look like a home appliance • It’s success caused IBM to build the PC • Influenced by Breakout • Visicalc, earliest spreadsheet, first ran on Apple IIe 1981: Xerox Star • Officially named Xerox 8010 Information System • First commercial system to incorporate various technologies that have since become standard in personal computers: • Bitmapped display, window-based graphical user interface • Icons, folders, mouse (two-button) • Ethernet networking, file servers, print servers, and e- mail. • Sold with software based on Lisp (early functional/AI language) and Smalltalk (early OO language) [Wikipedia, Fair Use] Xerox Star Evolution of “Document” Icon Shape [Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0] 1983: Apple Lisa [Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 2.0 fr] Apple Lisa • One of the first personal computers with a graphical user interface (GUI) • In 1982, Steve Jobs (Cofounder of Apple, with Steve Wozniak) was forced out of Lisa project, moved on into existing Macintosh project, and redefined Mac as cheaper, more usable version of Lisa • Lisa was challenged by relatively high price, insufficient SW library, unreliable floppy disks, and immediate release of Macintosh • Sold just about 10,000 units in two years • Introduced several advanced features that would not reappear on Mac or PC for many years Lisa Office -

The Identification and Division of Steve Jobs

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Scott M. Anderson for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies in Speech Communication, Speech Communication, and English presented on May 17, 2012. Title: The Identification and Division of Steve Jobs Abstract approved: Mark P. Moore On April 1, 1976, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak entered into a partnership agreement to found Apple Computer. In the decade that followed, Apple experienced remarkable growth and success, as Jobs catapulted Apple to the Fortune 500 list of top‐flight companies faster than any other company in history. Under direction of Jobs, Apple, an idea that started in a garage, transformed into a major force in the computer industry of the 1980s. Though Jobs’ leadership undoubtedly influenced Apple’s success during this time, in 1995, he was forced to resign, when conflicts mounted at the executive level. Using Kenneth Burke’s theory of identification and the dramatistic process, this thesis examines Jobs’ discourse through a series of interviews and textual artifacts. First, I provide a framework for Jobs’ acceptance and rejection of the social order at Apple, and then consider the ways in which Jobs identified with employee and consumer audiences on the basis of division. Analysis shows that Jobs identified with individual empowerment, but valued separation and exclusivity. Jobs’ preference to create identification through division, therefore, established the foundation for new identifications to emerge. The findings of this study suggest that division has significant implications for creating unity. ©Copyright by Scott M. Anderson May 17, 2012 All Rights Reserved The Identification and Division of Steve Jobs by Scott M. -

The History of Apple Inc

The History of Apple Inc. Veronica Holme-Harvey 2-4 History 12 Dale Martelli November 21st, 2018 Apple Inc is a multinational corporation that creates many different types of electronics, with a large chain of retail stores, “Apple Stores”. Their main product lines are the iPhone, iPad, and Macintosh computer. The company was founded by Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak and was created in 1977 in Cupertino, California. Apple Inc. is one of the world’s largest and most successful companies, recently being the first US company to hit a $1 trillion value. They shaped the way computers operate and look today, and, without them, numerous computer products that we know and love today would not exist. Although Apple is an extremely successful company today, they definitely did not start off this way. They have a long and complicated history, leading up to where they are now. Steve Jobs was one of the co-founders of Apple Inc. and one of first developers of the personal computer era. He was the CEO of Apple, and is what most people think of when they think ”the Apple founder”. Besides this, however, Steve Jobs was also later the chairman and majority shareholder of Pixar, and a member of The Walt Disney Company's board of directors after Pixar was bought out, and the founder, chairman, and CEO of NeXT. Jobs was born on February 24th, 1955 in San Francisco, California. He was raised by adoptive parents in Cupertino, California, located in what is now known as the Silicon Valley, and where the Apple headquarters is still located today. -

David T. Craig 941 Calle Mejia # 509, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 Home (505) 820-0358 Compuserve 71533,606

------------------------------------------------------- David T. Craig 941 Calle Mejia # 509, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 Home (505) 820-0358 CompuServe 71533,606 ------------------------------------------------------- Mr. Jef Raskin 8 Gypsy Hill Pacifica CA 94044 Re: Canon Cat and SwyftCard information Dear Mr. Raskin: Enclosed is a photocopy of the Canon Cat article that I wrote for the Historical Computer Society. The printed article is much better than the draft that you saw. Thanks for your help. Unfortunately, I was unable to obtain copies of all of your various articles concerning the Cat and Information Appliance. I did finally receive your LEAP paper from my local public library via inter-library loan, but the library could not locate your Venture Vulture paper. I received the LEAP paper after I had sent the final Cat paper for publication so was not able to correctly document LEAP's technology. In an e-mail to me from at least a month ago you said that if I sent you an envelope large enough for a SwyftCard and return postage that you would send me one. Please use the envelope that I've sent this letter in for this purpose. You should also find here self-sticking stamps for the postage and a mailing label with my mailing address. I would also very much like, if possible, to obtain a user's manual for the SwyftCard. From your comments in Microsoft's book Programmers at Work this manual seems to be very well written. There is no rush in returning this envelope so please take your time. I am slowly updating my Cat paper to add a correct description of LEAP and more information about the people behind the Cat and its hardware and software. -

Desktop Icon Era

Jason Hardware <p = class> </p> 20th Century Did you realize that computer weren’t born with a graphic user interface? It happened after over 30 years. 1962 Parts from four early computer. ORDVAC & BRLESC-I board On the first computers, with no operating system, every program needed the full hardware specification to run correctly and perform standard tasks, and its own drivers for peripheral devices like printers and punched paper card readers. Software <head> id = color, blue; </head> OSes Computer operating systems provide a set of functions needed and used by most application programs on a computer, and the links needed to control and synchronize computer hardware. Programming Language A programming language is a formal language, which comprises a set of instructions used to produce various kinds of output. Programming languages are used to create programs that implement specific algorithms. 80s Along with this revolutionary concept came other brilliant idea of using icons in computing. Sometimes, A picture says more than a thousand words. GUI- Graphic User Interface The history of the graphical user interface, understood as the use of graphic icons and a pointing device to control a computer, covers a five-decade span of incremental refinements, built on some constant core principles XEROX 8010 STAR 1981-1985 Invented by David Smith, Design by Norm Cox, it presented a square grid, simple looks, consistent style. APPLE-LISA 1983 Lisa was the first personal computer with a graphic user interface aimed at a wide audience of business customers. MACINTOSH 1 1984 Probably the most famous “art + Programming marriage” happened in 1982. -

Apple@30 1976-Apple in the Garage at the VCF 9.0

Apple@30 1976-Apple in the Garage At the VCF 9.0 Brought to you by… the DigiBarn Computer Museum the Vintage Computer Festival the Computer History Museum and a special group of Apple ’76ers Want to cook up an industry? Its easy! Just follow this convenient recipe… Apple@30 – the Ingredients Extraordinary People – some are here today… Deeply felt nerdly passions – homebrew computing …and there were many more Inspiring Places - Homestead High, HP, Atari, and of course, garages Apple@30 – the Recipe(s) Tasty recipes - TV Typewriter, 1973 Altair 8800, 1974 Homebrew club member reports, 1975 Apple@30 – the Kitchen(s) Steve Jobs parent’s garage, Crist Drive, Los Altos CA Inside the Jobs’ garage, 1976 Steve Wozniak’s workbench 1976 Apple@30 – the Chefs Master chefs Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak – then and now Apple@30 – cooking it up Apple 1 schematic, drawings - Spring 1976 Apple@30 – hot out of the oven! Apple 1 Apple@30 – out of the oven! Apple 1 in cool wooden case (Smithsonian) Apple@30 – out of the oven! Apple 1 screen, hex dump, test output Apple@30 – serving the Apple Apple’s first logo and first trade show Apple@30 – serving the Apple First ad for the Apple 1 Apple@30 – today’s feast Today’s Itinerary 1:00 Introduction of the event by host Sellam Ismail 1:05 Bruce Damer's slide show about Apple in 1976 and our panelists 1:20 Panelists weigh in on a freeform discussion of Apple… thirty years ago And in whatever order makes sense at the time: -Vince Briel shows the Apple 1 replica in operation -Linda Blum shows Jef Raskin’s original Apple -

Publications Core Magazine, 2007 Read

CA PUBLICATIONo OF THE COMPUTERre HISTORY MUSEUM ⁄⁄ SPRINg–SUMMER 2007 REMARKABLE PEOPLE R E scuE d TREAsuREs A collection saved by SAP Focus on E x TRAORdinARy i MAGEs Computers through the Robert Noyce lens of Mark Richards PUBLISHER & Ed I t o R - I n - c hie f THE BEST WAY Karen M. Tucker E X E c U t I V E E d I t o R TO SEE THE FUTURE Leonard J. Shustek M A n A GI n G E d I t o R OF COMPUTING IS Robert S. Stetson A S S o c IA t E E d I t o R TO BROWSE ITS PAST. Kirsten Tashev t E c H n I c A L E d I t o R Dag Spicer E d I t o R Laurie Putnam c o n t RIBU t o RS Leslie Berlin Chris garcia Paula Jabloner Luanne Johnson Len Shustek Dag Spicer Kirsten Tashev d E S IG n Kerry Conboy P R o d U c t I o n ma n ager Robert S. Stetson W E BSI t E M A n AGER Bob Sanguedolce W E BSI t E d ESIG n The computer. In all of human history, rarely has one invention done Dana Chrisler so much to change the world in such a short time. Ton Luong The Computer History Museum is home to the world’s largest collection computerhistory.org/core of computing artifacts and offers a variety of exhibits, programs, and © 2007 Computer History Museum. -

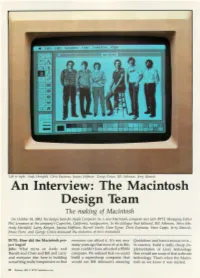

The Macintosh Design Team, February 1984, BYTE Magazine

Left to right: Andy Hertzfeld, Chris Espinosa, Joanna Hoffman , Geo rge Crowe, Bill Atkinson, Jern) Manock . An Interview: The Macintosh Design Team The making of Macintosh On October 14, 1983, the design team for Apple Computer Inc .'s new Macintosh computer met with BYTE Managing Editor Phil Lemmons at the company's Cupertino, California, headquarters. In the dialogue that followed , Bill Atkinson, Steve Jobs, Andy Hertzfeld, Larry Kenyon, Joanna Hoffman, Burrell Smith, Dave Egner, Chris Espinosa, Steve Capps, Jerry Manock, Bruce Horn , and George Crowe discussed the evolution of their brainchild. BYTE: How did the Macintosh pro everyone can afford it. It's not very Quickdraw and have a mouse on it ject begin? many years ago that most of us in this in essence, build a really cheap im Jobs: What turns on Andy and room couldn't have afforded a $5000 plementation of Lisa's technology Burrell and Chris and Bill and Larry computer. We realized that we could that would use some of that software and everyone else here is building build a supercheap computer that technology. That's when the Macin something really inexpensive so that would run Bill Atkinson's amazing tosh as we know it was started. 58 February 1984 © BYrE Publications Inc. Hertzfeld: That was around January of 1981. Smith: We fooled around with some other ideas for computer design, but we realized that the 68000 was a chip that had a future and had . .. Jobs: Some decent software! Smith: And had some horsepower and enough growth potential so we could build a machine that would live and that Apple could rally around for years to come. -

Apple's Mac Team Gathers for Insanely Great Twiggy Mac Reunion

Apple's Mac team gathers for insanely great Twiggy Mac reunion SILICON BEAT By Mike Cassidy Mercury News Columnist ([email protected] / 408-920-5536 / Twitter.com/mikecassidy) POSTED: 09/12/2013 11:57:40 AM PDT MOUNTAIN VIEW -- In Silicon Valley, it's not a question of "What have you done for me lately?" -- the question is, "So, what are you going to do for me next?" And so, you have to wonder what it's like to be best known for something you did 30 years ago. Randy Wigginton, one of the freewheeling pirates who worked under Steve Jobs on Apple's (AAPL) dent-in-the-world, 1984 Macintosh, has an easy answer. "It's awesome," says Wigginton, who led the effort on the MacWrite word processor. "People don't get to change the world very often. How much luckier can a guy be? I've had a very blessed life." The blessings were very much on Wigginton's mind the other day as he and a long list of early Apple employees got together to check out the resurrection of a rare machine known as the Twiggy Mac. The prototype was a key chapter in the development of the original Mac, which of course was a key chapter in the development of the personal computer and by extension the personal music player, the smartphone, the smart tablet and a nearly ubiquitous digital lifestyle that has turned the world on its head. Some of the key players in that story, first immortalized in Steven Levy's "Insanely Great" and again in Walter Isaacson's "Steve Jobs" and most recently, docudrama fashion, in the movie "Jobs," gathered at the Computer History Museum to get a look at the Mac and at old friends who'd done so much together. -

Hintz 1 DRAFT V1 – Please Do Not Cite Without Author's Permission. Susan

Hintz 1 Susan Kare: Design Icon by Eric S. Hintz, PhD Historian, Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution [email protected] SHOT SIGCIS – Works in Progress Session Albuquerque, NM October 11, 2015 DEAR COLLEAGUES: Thanks for reading this work-in-progress! I’m a SIGCIS rookie and relatively new to the history of computing. Thus, in terms of feedback, I’d appreciate a) some sense of whether this proposed article would have any traction within the scholarly/SIGCIS community and b) some help situating the story within the relevant secondary literature and historiography. Finally, given the largely non-archival sources I had to work with, I wrote this up more like a magazine feature (vs. scholarly article) so I’d also appreciate c) any suggestions for appropriate journals and publication venues. P.S. This article is ripe for lots of colorful images. Thanks! ESH Graphic designer Susan Kare has been called the “the Betsy Ross of the personal computer,” the “Queen of Look and Feel,” the “Matisse of computer icons,” and the “mother of the Mac trash can.”1 Indeed, Kare is best known for designing most of the distinctive icons, typefaces, and other graphic elements that gave the Apple Macintosh its characteristic—and widely emulated—look and feel. Since her work on the Mac during the early 1980s, Kare has spent the last three decades designing user interface elements for many of the leading software and Internet firms, from Microsoft and Oracle to Facebook and Paypal. Kare’s work is omnipresent in the digital realm; if you have clicked on an icon to save a file, switched the fonts in a document from Geneva to Monaco, or tapped your smart phone screen to launch a mobile app, then you have benefited from her designs. -

A Film Really About Heroines

“Steve Jobs”: A Film Really About Heroines Mark P. Barry February 1, 2016 When Steve Jobs died in 2011, his authorized biography was rushed to press, quickly followed by the low-budget, independent film, “Jobs.” Fans of the Apple CEO had to wait until last October for the full Hollywood production, “Steve Jobs,” featuring an A-list cast and team, to reach the big screen. Audiences were disappointed in the film because it bombed at the box office. Expectations surely were for a depiction of Jobs’ stellar technology and business achievements. But the truth is: this movie is more about its heroines than its hero. For her performance in “Steve Jobs,” Kate Winslet won the 2016 Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actress and is nominated for an Oscar this year as well. She plays Joanna Hoffman, long-time marketing chief at Apple and “right-hand woman” to its co-founder. Known as the one person who could stand up to the difficult and temperamental Jobs, in the film Hoffman calls herself his “work wife.” Winslet, as Joanna, is the moral center of the movie. Very loosely based on the Walter Isaacson official biography – a book Apple Mark P. Barry and Jobs’ family were not happy with – “Steve Jobs” is written by Aaron Sorkin, who won the 2011 Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for “The Social Network” and this year’s Golden Globe for Best Screenplay for “Steve Jobs.” “Steve Jobs” was lucky to get made. It was originally produced by Sony Pictures, but after North Korea hacked its computers in late 2014, divulging embarrassing executive emails, Universal Pictures acquired the film.