Volume 8 I 2011 Issn !824-7741

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8 - Olang 01.10.2018

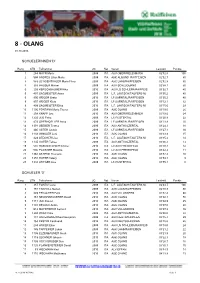

8 - OLANG 01.10.2018 SCHUELERINNEN 'D' Rang STN Teilnehmer JG Nat Verein Laufzeit Punkte 1 264 MAYR Marie 2009 ITA ASV OBERWIELENBACH 02'52.6 100 2 594 ANDRES Lilian Marie 2009 ITA ASC ALGUND RAIFFEISEN 02'52.7 80 3 583 SCHOENTHALER Marie Flora 2009 ITA ASC LAAS/RAIFFEISEN 02'52.8 60 4 303 HAUSER Miriam 2009 ITA ASV SCHLUDERNS 02'58.1 50 5 238 KERSCHBAUMER Nika 2010 ITA ASV LG SCHLERN/RAIFFEIS 03'02.7 45 6 407 SAGMEISTER Anna 2009 ITA L.F. LAATSCH/TAUFERS M. 03'05.2 40 6 856 WEGER Greta 2010 ITA LF SARNTAL/RAIFFEISEN 03'05.2 40 8 857 WEGER Klara 2010 ITA LF SARNTAL/RAIFFEISEN 03'12.1 32 9 408 SAGMEISTER Elisa 2010 ITA L.F. LAATSCH/TAUFERS M. 03'15.6 29 10 1106 FONTANA Maria Theres 2009 ITA ASC OLANG 03'19.0 26 11 254 KNAPP Lea 2010 ITA ASV OBERWIELENBACH 03'19.6 24 12 1325 JUD Petra 2009 ITA LC PUSTERTAL 03'20.9 22 13 473 OBERHOELLER Anna 2009 ITA LF SARNTAL/RAIFFEISEN 03'23.8 20 14 1301 SEEBER Teresa 2009 ITA ASV ANTHOLZERTAL 03'24.1 18 15 460 ASTER Jasmin 2009 ITA LF SARNTAL/RAIFFEISEN 03'27.3 16 16 1133 WINKLER Leni 2010 ITA ASC OLANG 03'33.9 15 17 428 STECHER Lisa 2010 ITA L.F. LAATSCH/TAUFERS M. 03'35.4 14 18 1135 HOFER Tabea 2009 ITA ASV ANTHOLZERTAL 03'36.3 13 19 507 RABENSTEINER Emma 2010 ITA LV ASV FREIENFELD 03'38.4 12 20 506 PLAIKNER Melanie 2010 ITA LV ASV FREIENFELD 03'42.2 11 21 1363 SCHENK Theresia 2010 ITA ASC OLANG 03'52.4 10 22 1357 HOFER Valery 2010 ITA ASC OLANG 03'54.1 9 23 1333 LEITGEB Lisa 2009 ITA LC PUSTERTAL 03'55.1 8 SCHUELER 'D' Rang STN Teilnehmer JG Nat Verein Laufzeit Punkte 1 387 FONTO' Luca 2009 ITA L.F. -

Citybus Olang Citybus Valdaora

435 Citybus Olang Citybus Valdaora Percha-Bruneck Rasen-Antholz Perca-Brunico Rasun-Anterselva Percha-Bruneck Neunhäusern Abzweigung Olang Toblach-Innichen Perca-Brunico Nove Case Bivio Valdaora Dobbiaco-S.Candido Fernheizwerk Teleriscaldamento Rienz - Rienza Schwimmbad Piscina Olang Bahnhof Pfarrbäck Valdaora Stazione 400 Abzw.Niederolang Bruneck-Franzensfeste Brunico-Fortezza Bv.Valdaora d.Sotto Niederolang Kirche Oberrain Valdaora di Sotto Chiesa Erlenweg Via Ontani Rodelbahnweg Via d. Slittino Niederolang Innichen-Lienz Valdaora di Sotto Pichlweg San Candido-Lienz Via Pichl Mitterolang Rathaus Valdaora d.Mezzo Municipio CITYBUS Olang Valdaora Mittelschule Olang Oberolang Mitterolang Scuola Media Valdaora Valdaora di Sopra Mitterhof Valdaora di Mezzo Oberolang Schule Vald.d.Sopra Scuola Gassl Abzw. Panorama Winkelwiese Geiselsberg Bivio Panorama Sorafurcia Olang Kabinenbahn Valdaora Cabinovia Oberolang Valdaora di Sopra CITYBUS OLANG 11.12.2016-09.12.2017 435 CITYBUS VALDAORA TÄGLICHX X X X X X 2 2 2 X X X X 400 von Innichen an 5.44 6.14 6.44 7.14 7.44 8.14 7 8.44 7 9.44 7 10.44 7 11.44 12.14 7 12.44 13.14 a. 400 da S. Candido 400 von Bruneck an 6.44 7.14 7.44 8.14 8.44 9.44 10.44 11.44 7 12.14 12.44 7 13.14 a. 400 da Brunico Bahnhof Olang 5.48 6.18 6.48 7.18 7.48 8.18 8.48 9.48 10.48 11.48 12.18 12.48 13.18 Stazione di Valdaora Abzweigung Niederolang 5.51 6.21 7.21 7.51 8.21 8.51 9.51 10.51 11.51 12.21 13.21 Bivio Valdaora di Sotto Niederolang, Pfarrbäck 5.54 6.24 7.24 7.54 8.24 11.54 12.24 13.24 Valdaora di Sotto, Pfarrbäck Abzweigung -

Alps Active: Programma Settimanale Bici & Escursioni Sull'alpe Di Siusi

Schlernstr. 39 | Via Sciliar I-39040 Seis | Siusi Tel. +39 0471 727 909 [email protected] | www.alps-activ.com Weekly program Mountain Valley Bike Bike & hike Hike Bike Hike easy easy E-Bike Technique Training Panoramawanderung Seiser Alm Kostenlos / Gratuito / Free Escursione panoramica Alpe di Siusi Start / Partenza: 8:45 am Office Alps Activ mon Panoramic hike Seiser Alm medium Kostenlos / Gratuito / Free E-Bike | Völser Weiher - Tuffalm Start / Partenza: 10:30 Uhr Infobüro Compatsch / ore 10:30 Tour con E-Bike | Laghetti di Fie - Malga Tuff uff. turistico Compatsch / 10:30 am tourist office Compatsch Kostenlos / Gratuito / Free Start / Partenza: 11:00 am Office Alps Activ easy easy 25 €/Pers. easy E-Bike-Tour Seiseralm Sonnenaufgang Puflatsch inkl. Frühstück St. Valentin - Marinzen - Schafstall Tour con E-Bike Alpe di Siusi Alba sulla Bullaccia incl. colazione tue Sunrise on Puflatsch incl. breakfast S. Valentino - Marinzen - Schafstall Kostenlos / Gratuito / Free Auf Bezahlung / A pagamento / On payment Kostenlos / Gratuito / Free Start / Partenza: 10:00 Uhr Infobüro Compatsch / ore 10:00 Start / Partenza: Abholung im Hotel / ritiro al hotel / Start / Partenza: 10:00 Uhr Büro Alps Activ / ore 10:00 uff. turistico Compatsch / 10:00 am tourist office Compatsch pick up at Hotel Ufficio Alps Activ / 10:00 am Office Alps Activ medium medium Entdeckungstour Unesco World Heritage Alla scoperta del patrimonio Unesco Tiers - Tschafon - Völser Weiher wed Unesco World Heritage discovery tour Tires - Tschafon - Laghetti di Fiè Kostenlos / -

Campitello – 5 Day Ski Itinerary

Campitello – 5 Day Ski Itinerary Easy Medium Hard Day 1: The Local Fields - Grade: From either Campitello or Canazei ski lifts explore the local ski areas of Col Rodella (Campitello) and Belvedere (Canazei). Both fields offer intermediate terrain with a few steep sections that are easy to see. There are some wonderful long runs with the best being the run to the valley from the cable car at Col Rodella. You can ski to the village of Canazei from both fields. If you want to follow the sun, it is best to ski Col Rodella in the morning and Belvedere in the afternoon. Both ski areas are connected by a telecabine (lift numbers 155 and 105) and so access is easy. Highlights The skiing: From Belvedere make sure you ski down to the Pordoi pass and take the lift to Sass Pordoi for a spectacular view of the dolomites. Sass Pordoi featured in the film Cliff Hanger. You should not ski down from here – all of the runs from the top are off piste, unpatrolled and extremely dangerous. Take the cable car back down and ski. Eating: There are a number of great places to eat on the mountain. Our favourites are Tita Piaz and Ciampolin at Belvedere and Rifugio Des Alpes and Salei on Col Rodella. Stop before 1pm to beat the crowds – Italians religiously stop for lunch at this time. Apres Ski: The round bar at Des Alpes in the afternoon. If you're skiing back to Canazei, make sure you leave before the slopes close. Day 2: Ski Val Gardena - Grade: Val Gardena – the home of the world cup downhill piste is also an easy first tour from the Fassa Valley. -

Passeirer Blatt

www.passeier.net BCDA 12 0cdeab Versand im Postabo. – 70% – Filiale Bozen – 70% im Postabo. Versand Passeirer Blatt i. p. April 2008 nr. 87 · 22. jahrgang Werner Heel April 2008 April Der erste Passeirer, der ein Ski-Weltcuprennen gewinnen konnte! Mitteilungen und Nachrichten aus Moos, St. Leonhard und St. Martin Leonhard und St.Mitteilungen und Nachrichten aus Moos, St. Blatt inhalt 2 gemeinden 3 kultur & gesellschaft 4 passeier vor hundert jahren 12 natur & umwelt Passeirer Foto R. Perathoner 13 wirtschaft 15 vereine & verbände 21 gesundheit & soziales 21 geburten 23 schulen & kindergärten Wir gratulieren herzlich 27 kinderseite 28 sport zu dieser außergewöhnlichen Leistung! 31 vorankündigungen 113.indd3.indd 1 114-04-20084-04-2008 7:27:457:27:45 2 gemeinden gemeinde moos dass eine Kartographie, bzw. die digitale grafi sche Darstellung derselben noch GIS-Projekt – lange kein GIS ist. Hierfür benötigen wir in erster Linie Daten. Dabei kann sich das Leitungskataster System zum einen auf vorhandene Daten- banken, wie z. B. Meldeamt, Steueramt, Bereits im Jahr 2007 hat die Gemeindever- Katasteramt usw. stützen. Für verschie- waltung von Moos Flugaufnahmen des dene andere Anwendungen ist es jedoch besiedelten Gebietes im Ausmaß von ca. notwendig, die entsprechenden Infra- 500 ha in Auftrag gegeben. Auf Basis die- strukturen und Anlagen sowohl graphisch ser Orthofotos wurde eine technische als auch beschreibungsmäßig erst einmal Grundkarte im Maßstab 1 : 1000 erstellt. zu erheben. Nachdem inhaltlich im GIS Diese Arbeiten mit einem Kostenaufwand einer Gemeinde vor allem die öffentlichen von ca. 90.000 Euro wurden von der Firma Infrastrukturen wie Trinkwasserleitun- Geomatica S.r.l. aus Lavis (TN) durchge- gen, Abwasserleitungen, Weißwasserlei- führt. -

Tag Der Artenvielfalt 2019 in Altprags (Gemeinde Prags, Südtirol, Italien)

Thomas Wilhalm Tag der Artenvielfalt 2019 in Altprags (Gemeinde Prags, Südtirol, Italien) Keywords: species diversity, Abstract new records, Prags, Braies, South Tyrol, Italy Biodiversity Day 2019 in Altprags (municipality of Prags/Braies, South Tyrol, Italy) The 20th South Tyrol Biodiversity Day took place in Altprags in the municipality of Braies in the Puster Valley and yielded a total of 884 identified taxa. Four of them are new for South Tyrol. Einleitung Der Südtiroler Tag der Artenvielfalt fand 2019 am 22. Juni in seiner 20. Ausgabe statt. Austragungsort war Altprags in der Gemeinde Prags im Pustertal. Die Organisation lag in den Händen des Naturmuseums Südtirol unter der Mitwirkung des Amtes für Natur und des Burger-Hofes vom Schulverbund Pustertal. Bezüglich Konzept und Organisation des Südtiroler Tages der Artenvielfalt siehe HILPOLD & KRANEBITTER (2005) und SCHATZ (2016). Adresse der Autors: Thomas Wilhalm Naturmuseum Südtirol Bindergasse 1 I-39100 Bozen thomas.wilhalm@ naturmuseum.it eingereicht: 25.9.2020 angenommen: 10.10.2020 DOI: 10.5281/ zenodo.4245045 Gredleriana | vol. 20/2020 119 | Untersuchungsgebiet ins Gewicht fallende Gruppen, allen voran die Hornmilben und Schmetterlinge, nicht bearbeitet werden. Auch das regnerische Wetter war bei einigen Organismengruppen Das Untersuchungsgebiet lag in den Pragser Dolomiten in der Talschaft Prags und zwar dafür verantwortlich, dass vergleichsweise wenige Arten erfasst wurden. im östlichen, Altprags genannten Teil. Die für die Erhebung der Flora und Fauna ausge- wiesene Fläche erstreckte sich südöstlich des ehemaligen Bades Altprags und umfasste im Tab. 1: Südtiroler Tag der Artenvielfalt am 22.6.2019 in Altprags (Gemeinde Prags, Südtirol, Italien). Festgestellte Taxa in den Wesentlichen die „Kameriotwiesen“ im Talboden sowie die Südwesthänge des Albersteins erhobenen Organismengruppen und Zahl der Neumeldungen. -

Dolomites Offer Delightful Via Ferratas

spring-loaded device, which, if a fall takes place, will minimize the impact on the climber who is usually linked to a fixed cable. I sometimes used my climbing shoes whereas Helmut used his lightweight mountaineering boots. Most ferrata climb- ers hung on to the cables, whereas we mostly free climbed with a few exceptions. Upon arrival from Munich, Helmut, his wife, Giselle, and I checked in at the Hotel Christiania in Alta Badia/Stern, where Helmut had stayed previ- ously several times. Full board and lodging were very much appreciated. All approaches to the climbs were comfortably accomplished in a day from this elegant hotel, where we could always have a full breakfast, afternoon snacks and dinner in the evenings. Although the weather forecast for the first week was for rain showers, we enjoyed sunshine every day for the following 11 days, except when cloud and thunderstorms sometimes moved in late in the afternoons and/or evenings. The next day, Helmut led me to my first ferrata, Pizzes da Cir; a perfect introduction to the ferratas being a short but pleasant route, starting from a chairlift. The following day, after paying a heavy toll for the private access road to one of the best known ferratas in the Dolomites, we hiked along with hundreds of other tourists to the start of the De Luca/Innerkofler protected wartime climbing path, which, partway along, includes a 400-metre tunnel (headlamp required). We enjoyed a fairly long day in good weather. For our next outing, Diego was our guide to climb Cinque Dita (five fin- gers) in the Sasso Lungo Langkofel group, leading to a 2996-metre summit. -

Dolomiten Dolomiti Dolomites

Reinhold Messner Dolomiten Dolomiti Dolomites Die schönsten Berge der Welt – UNESCO Welterbe Dolomites Le montagne più belle del mondo – Patrimonio mondiale UNESCO The most beautiful mountains in the world – UNESCO World Heritage Site athesia-tappeiner.com9,90 € (I/D/A) Dolomiti Dolomiten Reinhold Messner Umschlag-Titelseite: Oben links: der Schlern | Oben Mitte: der Rosengarten | Oben rechts: das Ranuikirchlein und die Geislerspitzen Unten links: der Langkofel | Unten Mitte: der Sellastock | Unten rechts: die Drei Zinnen Umschlag-Rückseite: Oben links: die Brentagruppe | Oben Mitte: der Monte Agnèr | Oben rechts: der Heiligkreuzkofel Unten links: der Lago di Coldai und Monte Pelmo | Unten Mitte: die Marmolata | Unten rechts: der Monte Cristallo Foto di copertina: In alto a sinistra: lo Sciliar | In alto al centro: il Catinaccio | In alto a destra: la chiesetta di Ranui e le Odle In basso a sinistra: il Sassolungo | In basso al centro: il Gruppo di Sella | In basso a destra: le Tre Cime di Lavaredo Retrocopertina: In alto a sinistra: il Gruppo di Brenta | In alto al centro: il Monte Agnèr | In alto a destra: il Sasso di Santa Croce In basso a sinistra: il Lago di Coldai e il Monte Pelmo | In basso al centro: la Marmolada | In basso a destra: il Monte Cristallo Cover photos Top left: the Schlern | Top centre: the Rosengarten | Top right: Ranui chapel and the Geislerspitzen Bottom left: the Langkofel group | Bottom centre: the Sella massif | Bottom right: the Drei Zinnen Back cover: Top left: the Brenta group | Top centre: the Monte Agnèr | Top right: the Heiligkreuzkofel Bottom left: the Monte Pelmo with Lake Coldai | Bottom centre: the Marmolada | Bottom right: the Monte Cristallo Die vergletscherte Nordseite der Marmolata Il versante nord della Marmolada coperto di ghiaccio The glaciated north side of the Marmolada Inhalt | Indice | Content Dolomiten UNESCO Welterbe | Dolomiti Patrimonio mondiale UNESCO | Dolomites UNESCO World Heritage Site . -

The Grand Tour

The Grand Tour IT’S NOT JUST ABOUT EPIC ROADS... March 26th - 28th, 2021 IT’S AN EXTRAORDINARY CULINARY EXPERIENCE for the most demanding gourmets NORBERT NIEDERKOFLER St. Hubertus With 3 Michelin stars, the St. Hubertus Restaurant is the pride of the Hotel & Spa Rosa Alpina. With only 11 tables, it is as exclusive as it is elegant. It was born in 1996 and owes its name to the Saint protector of hunters. The dining experience is best summed up in the words of chef Norbert Niederkofler: “The variety comes from mixing simplicity. The best product is the basic assumption. I put my effort in respecting the product and enhance it using the right cooking method. The result must be “visible” both in the taste and in its aesthetic, it must be delicate and simple but still surprising. The lightness can be seen and tasted”. Photo of Norbert and Luigi prior to Covid19 PAOLO DONEI Malga Panna The chef Paolo Donei was awarded with a Michelin star when he was only 19 years old and has maintained it for over 20 years thanks to his authentic cooking, that respects the traditions of Trentino and the nature surrounding the Malga Panna restaurant. RENZO DAL FARRA Locanda San Lorenzo The restaurant’s history goes back to January 7th, 1900 from a very passionate family. Here chef Renzo Dal Farra gets everybody excited with a very traditional cuisine made of local products but still very contemporary. DAY 1 DAY 2 DAY 3 Trentino Alto Adige St. Hubertus GARDENA PASS FALZAREGO PASS SELLA PASS PORDOI PASS GIAU PASS SAN PELLEGRINO PASS Malga Panna Rifugio Fuciade Locanda San Lorenzo Veneto FRIDAY 12:00 - Event check-in at Restaurant Malga Panna in Moena Welcome lunch prepared by Chef Paolo Donei After lunch, a scenic route less than 2 hours long will take us across the Sella Mountain, going through Passo Sella and Passo Gardena, two of the four famous passes around the Sella Mountain, and then down to Val Badia where we will reach the hotel in San Cassiano. -

Pre-Race Press Release

s July 2014 Maratona dles Dolomites – Enel 2014 PRE-RACE PRESS RELEASE ADDRESS BY THE PRESIDENT MICHIL COSTA Life is made up of moments which are not experienced necessarily in sequence and which do not represent a slice of time. Moments have their own existence and consistency. You may be able to spend here many beautiful moments, important moments, moments of life. “Giulan” for your contribution in making the marathon important, “Giulan” for being here. 9,000 CYCLISTS FROM ALL OVER THE WORLD FOR THE 28TH EDITION. (Alta Badia – Alto Adige). On Sunday 6th July, the departure is fixed for 6.30 a.m. from La Villa. The arrival is always in Corvara for the most famous long distance cycling race in Europe. As every year, the closed number guarantees the race runs perfectly for the over 9,000 cyclists drawn, representing 58 nationalities, to meet the over 32,600 entry applications, which arrived in a few days in October 2013, the opening date for entries. The legendary Campolongo, Sella, Pordoi, Gardena, Giau, Falzarego and Valparola Passes, completely closed to traffic, will allow them to tackle the three race routes: Long 138 km and a climb of 4230 metres, Medium of 106 km and a climb of 3130 metres and Sella Ronda of 55 km and a climb of 1780 metres. THE WALL OF THE CAT – THE GREAT NEW FEATURE OF THE 28TH MARATONA DLES DOLOMITES-ENEL 2014! The great innovation for all the cyclists on the medium route (at the 101st kilometre) and on the long route (at the 133rd km). -

Tectonostratigraphy of the Western Dolomites in the Context of the Development of the Western Tethys 51-56 Geo.Alp, Vol

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Geo.Alp Jahr/Year: 2019 Band/Volume: 0016 Autor(en)/Author(s): Brandner Rainer, Gruber Alfred Artikel/Article: Tectonostratigraphy of the Western Dolomites in the context of the development of the Western Tethys 51-56 Geo.Alp, Vol. 16 2019 TECTONOSTRATIGRAPHY OF THE WESTERN DOLOMITES IN THE CONTEXT OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE WESTERN TETHYS → Rainer Brandner 1 & Alfred Gruber 2 1 Institut für Geologie, Universität Innsbruck, Austria; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Geologische Bundesanstalt, Wien, Austria; e-mail: [email protected] In the Dolomites, the transition from the post-Variscan to into Central Europe ("Central European Extensional Province", the Alpine orogen cycle generally takes place in a domain of Kroner et al., 2016) and is accompanied by the widespread lithospheric stretching, which is recorded in several plate thermal event ("Permian metamorphic event", Schuster & tectonically controlled megacycles in the sediment sequences. Stüwe, 2008). Early Permian and Middle Triassic magmatism are associated with this development. In contrast to the "post-Variscan" magmatism, however, the Middle Triassic magmatism gives 2ND TECTONOSTRATIGRAPHIC MEGACYCLE (MIDDLE PERMIAN TO rise to numerous discussions due to its orogenic chemistry LOWER ANISIAN) in the extensional setting of the Dolomites. A new analysis of the tectonostratigraphic development now revealed an With the cooling of the crust, continental and marine interpretation of the processes that differs from the general sedimentation starts in large areas in the Middle and Upper opinion. Within the general extensional development in the Permian, which overlaps the graben-like extensional tectonics Permo-Mesozoic there are four distinct unconformities caused relief like mantle (see Wopfner, 1984 and Italian IGCP 203 Group, by compressive or transpressive tectonic intervals. -

Hyperspectral Remote Sensing 6 Data Analysis and Future Challenges by José M

Contents | Zoom in | Zoom outFor navigation instructions please click here Search Issue | Next Page Contents | Zoom in | Zoom outFor navigation instructions please click here Search Issue | Next Page qM qMqM Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page qMqM Qma gs THE WORLD’S NEWSSTAND® CALL FOR PAPERS IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine This is the second issue of the new IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine, which was approved by the IEEE Technical Activities Board in 2012. This is an important achievement for GRSS since it has never had a publication in the magazine format. The magazine will provide a new venue to publish high quality technical articles that by their very nature do not find a home in journals requiring scientific innovation but that provide relevant information to scientists, engineers, end-users, and students who interact in different ways with the geoscience and remote sensing disciplines. The magazine will publish tutorial papers and technical papers on geoscience and remote sensing topics, as well as papers that describe relevant applications of and projects based on topics addressed by our society. The magazine will also publish columns on: - New satellite missions - Standard remote sensing data sets - Education in remote sensing - Women in geoscience and remote sensing - Industrial profiles - University profiles - GRSS Technical Committee activities - GRSS Chapter activities - Conferences and workshops. The new magazine is published in with an appealing layout, and its articles will be included with an electronic format in the IEEE Xplore online archive. The Magazine content is freely available to GRSS members.