Webster (1999) Notes (Pdf 200K)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![177] Decentralization Are Implemented and Enduringneighborhood Organization Structures, Social Conditions, and Pol4ical Groundwo](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2150/177-decentralization-are-implemented-and-enduringneighborhood-organization-structures-social-conditions-and-pol4ical-groundwo-192150.webp)

177] Decentralization Are Implemented and Enduringneighborhood Organization Structures, Social Conditions, and Pol4ical Groundwo

DOCUMENT EESU E ED 141 443 UD 017 044 .4 ' AUTHCE Yates, Douglas TITLE Tolitical InnOvation.and Institution-Building: TKe Experience of Decentralization Experiments. INSTITUTION Yale Univ., New Haven, Conn. Inst. fOr Social and Policy Studies. SEPCET NO W3-41 PUB DATE 177] .NCTE , 70p. AVAILABLEFECM Institution for Social and,Policy Studies, Yale tUniversity,-',111 Prospect Street,'New Haven, Conn G6520. FEES PRICE Mt2$0.83 HC-$3.50.Plus Postage. 'DESCEIPTORS .Citizen Participation; City Government; Community Development;,Community Involvement; .*Decentralization; Government Role; *Innovation;. Local. Government; .**Neighborflood; *Organizational Change; Politics; *Power Structure; Public Policy; *Urban Areas ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to resolve what determines the success or failure of innovations in Participatory government; and,-more precisely what are the dynamics of institution-building by which the 'ideas of,participation arid decentralization are implemented and enduringneighborhood institutions aTe established. To answer these questiOns, a number of decentralization experiments were examined to determine which organization structures, Social conditions, and pol4ical arrangements are mcst conducive io.sucCessful innov,ation and institution -building. ThiS inquiry has several theoretical implications:(1) it.examines the nature and utility of pOlitical resources available-to ordinary citizens seeking to influence.their government; 12L it comments on the process of innovation (3) the inquiry addresses ihe yroblem 6f political development, at least as It exists in urban neighborhoods; and (4)it teeks to lay the groundwork fca theory of neighborhood problem-solving and a strategy of reighborhood development. (Author)JM) ****************44**************************************************** -Documents acquired by EEIC,include many Informal unpublished * materials nct available frOm-other sources. ERIC makes every effort * to obtain.the test copy available. -

Bidang Usaha Non Konstruksi Tahun 2014

DAFTAR PERUSAHAAN JASA PENUNJANG MIGAS PERATURAN MENTERI ENERGI DAN SUMBER DAYA MINERAL NO. 27 TAHUN 2008 BIDANG USAHA JASA NON KONSTRUKSI 2014 Nomor PERUSAHAAN kode SUB BIDANG USAHA ALAMAT TELEPON / FAX PIMPINAN S K T Tanggal 1 PT Raja Janamora Lubis p. Jasa Penyedia Tenaga Kerja: Tenaga Pemboran: Jalan Bakti Abri Gang Swadaya II Telp:(021) 46351155 Yudi Susanto Lubis 0001/SKT-02/DMT/2014 2-Jan-14 Operator Lantai Bor, Operator Menara Bor, Juru RT/RW 02/09 No. 38 - Depok Fax: (021) 46222485 Bor, Ahli Pengendali Bor, dan Rig Superintendent 2 PT Waviv Technologies a. Survei Seismik: Pengolahan Data Seismik (Seismic Gedung Bursa Efek Indonesia Telp:(021) 5155955 Pandu Utama Witadi 0002/SKT-02/DMT/2014 2-Jan-14 Data Processing) Tower 1 Lantai 15 Suite 102 - Fax:(021) 5155955 Jalan Jenderal Sudirman Kav. 52- 53 - Jakarta 3 PT Waviv Technologies b. Survei Non Seismik: Survei Geologi, Survei Gedung Bursa Efek Indonesia Telp:(021) 5155955 Pandu Utama Witadi 0003/SKT-02/DMT/2014 2-Jan-14 Geofisika, Survei Oseanografi (Metocean Survey) Tower 1 Lantai 15 Suite 102 - Fax:(021) 5155955 Jalan Jenderal Sudirman Kav. 52- 53 - Jakarta 4 PT Waviv Technologies c. Geologi dan Geofisika: Interpretasi Data Seismik, Gedung Bursa Efek Indonesia Telp:(021) 5155955 Pandu Utama Witadi 0004/SKT-02/DMT/2014 2-Jan-14 Interpretasi Data Geologi dan Geofisika, Tower 1 Lantai 15 Suite 102 - Fax:(021) 5155955 Permodelan Reservoir (Reservoir Modeling) Jalan Jenderal Sudirman Kav. 52- 53 - Jakarta 5 PT Waviv Technologies p. Jasa Penyedia Tenaga Kerja: Tenaga Survei Gedung Bursa Efek Indonesia Telp:(021) 5155955 Pandu Utama Witadi 0005/SKT-02/DMT/2014 2-Jan-14 Seismik: Juru Ukur Seismik, Juru Tembak Seismik, Tower 1 Lantai 15 Suite 102 - Fax:(021) 5155955 Ahli Topografi Seismik, Ahli Rekam Seismik, Ahli Jalan Jenderal Sudirman Kav. -

AGENDA REV 5 1.Indd

DEWAN PERWAKILAN DAERAH REPUBLIK INDONESIA AGENDA KERJA DPD RI 2017 DATA PRIBADI Nama __________________________________________________________ No. Anggota ___________________________________________________ Alamat _________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ Telepon/Fax ____________________________________________________ Nomor _________________________________________________________ KTP ____________________________________________________________ Paspor _________________________________________________________ Asuransi _______________________________________________________ Pajak Pendapatan ______________________________________________ SIM ____________________________________________________________ PBB ____________________________________________________________ Lain-lain _______________________________________________________ DATA BISNIS Kantor _________________________________________________________ Alamat _________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ Telepon/Fax ____________________________________________________ Telex ___________________________________________________________ Lain-lain _______________________________________________________ NOMOR TELEPON PENTING Dokter/Dokter Gigi _____________________________________________ Biro Perjalanan _________________________________________________ Taksi ___________________________________________________________ Stasiun K.A -

Political Development Theory in the Sociological and Political Analyses of the New States

POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT THEORY IN THE SOCIOLOGICAL AND POLITICAL ANALYSES OF THE NEW STATES by ROBERT HARRY JACKSON B.A., University of British Columbia, 1964 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Political Science We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, I966 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission.for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Polit_i_g^j;_s_gience The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date September, 2, 1966 ii ABSTRACT The emergence since World War II of many new states in Asia and Africa has stimulated a renewed interest of sociology and political science in the non-western social and political process and an enhanced concern with the problem of political development in these areas. The source of contemporary concepts of political development can be located in the ideas of the social philosophers of the nineteenth century. Maine, Toennies, Durkheim, and Weber were the first social observers to deal with the phenomena of social and political development in a rigorously analytical manner and their analyses provided contemporary political development theorists with seminal ideas that led to the identification of the major properties of the developed political condition. -

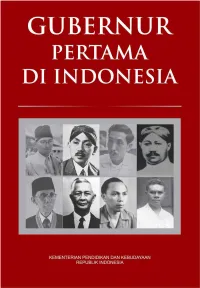

Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R

GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA PENGARAH Hilmar Farid (Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan) Triana Wulandari (Direktur Sejarah) NARASUMBER Suharja, Mohammad Iskandar, Mirwan Andan EDITOR Mukhlis PaEni, Kasijanto Sastrodinomo PEMBACA UTAMA Anhar Gonggong, Susanto Zuhdi, Triana Wulandari PENULIS Andi Lili Evita, Helen, Hendi Johari, I Gusti Agung Ayu Ratih Linda Sunarti, Martin Sitompul, Raisa Kamila, Taufik Ahmad SEKRETARIAT DAN PRODUKSI Tirmizi, Isak Purba, Bariyo, Haryanto Maemunah, Dwi Artiningsih Budi Harjo Sayoga, Esti Warastika, Martina Safitry, Dirga Fawakih TATA LETAK DAN GRAFIS Rawan Kurniawan, M Abduh Husain PENERBIT: Direktorat Sejarah Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Jalan Jenderal Sudirman, Senayan Jakarta 10270 Tlp/Fax: 021-572504 2017 ISBN: 978-602-1289-72-3 SAMBUTAN Direktur Sejarah Dalam sejarah perjalanan bangsa, Indonesia telah melahirkan banyak tokoh yang kiprah dan pemikirannya tetap hidup, menginspirasi dan relevan hingga kini. Mereka adalah para tokoh yang dengan gigih berjuang menegakkan kedaulatan bangsa. Kisah perjuangan mereka penting untuk dicatat dan diabadikan sebagai bahan inspirasi generasi bangsa kini, dan akan datang, agar generasi bangsa yang tumbuh kelak tidak hanya cerdas, tetapi juga berkarakter. Oleh karena itu, dalam upaya mengabadikan nilai-nilai inspiratif para tokoh pahlawan tersebut Direktorat Sejarah, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan menyelenggarakan kegiatan penulisan sejarah pahlawan nasional. Kisah pahlawan nasional secara umum telah banyak ditulis. Namun penulisan kisah pahlawan nasional kali ini akan menekankan peranan tokoh gubernur pertama Republik Indonesia yang menjabat pasca proklamasi kemerdekaan Indonesia. Para tokoh tersebut adalah Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R. Pandji Soeroso (Jawa Tengah), R. -

Plagiat Merupakan Tindakan Tidak Terpuji

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PEMBENTUKAN DAN PEMBUBARAN NEGARA REPUBLIK INDONESIA SERIKAT 1949-1950 SKRIPSI Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah Oleh: Leonardo Nim : 011314043 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN ILMU PENGETAHUAN SOSIAL FAKULTAS KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2007 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI iii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN Atas dasar cinta, skripsi ini kupersembahkan kepada: Ø Tuhanku penguasa alam semesta yang dengan setia selalu menjaga dan mendampingi setiap langkah dalam hidupku. Ø Papa dan ibu tercinta, terimakasih atas pengorbanan, perjuangan, kepercayaan, dan kasih sayangnya. Ø Mama yang ada di surga yang telah memberikan nafas kehidupan. Ø Kedua Adikku tersayang, Riko dan Berto yang telah menjadi aspirasi putih dalam mencapai tujuanku. Ø Seluruh keluarga Besarku yang bukan rahasia lagi selalu mendoakanku. Ø Separuh nafasku Lina Ndu’ Ku Dwiyanti, terimakasih telah menemaniku dengan penuh ketulusan dan keikhlasan, kamulah satu-satunya. Ø Laskar Cinta 291 dan Ex 291, tebarkanlah benih-benih cinta dan musnahkanlah virus-virus benci. Ø Keluarga besar 291 (Pak Parno, Ibu Yayuk), terimakasih atas semuanya. Ø Sedulur-sedulur angkatan ’01 Ovie, Siska, Jonni Van Ann, Maria, Era, Ida Bolon, Lippo, Mas dab Suryatno, dan yang tak bisa di sebut satu persatu. Ø Almamaterku tercinta Prodi pendidikan Sejarah -

Sultan Hamid Ii Berwajah Ganda Dalam Karier Politiknya Di Indonesia Makalah

PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI SULTAN HAMID II BERWAJAH GANDA DALAM KARIER POLITIKNYA DI INDONESIA MAKALAH Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah Oleh: VINSENSIUS 101314006 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN ILMU PENGETAHUAN SOSIAL FAKULTAS KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2015 PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI SULTAN HAMID II BERWAJAH GANDA DALAM KARIER POLITIKNYA DI INDONESIA MAKALAH Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah Oleh: VINSENSIUS 101314006 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN ILMU PENGETAHUAN SOSIAL FAKULTAS KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2015 i PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI ii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI iii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI PERSEMBAHAN Makalah ini saya persembahkan kepada: 1. Yesus Kristus, Bunda Maria, Bapa Yosef, serta Santo Vinsensius pelindung saya yang telah memberikan kesempatan, semangat dan pencerahan sehingga karya tulisan ini dapat terselesaikan. 2. Kedua orangtuaku Bapak Jongki dan Ibu Merensiana Sa’arin yang telah membesarkanku, kedua kakak Agapitus, Adria Utami Yosa dan adik tercinta Eligia Suriati serta tidak -

GOVERNMENT and POLITICS of CHINA Spring Semester 2015 - MW 2:00-3:20 W Ooten Hall 116

GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS OF CHINA Spring Semester 2015 - MW 2:00-3:20 W ooten Hall 116 David Mason 940-565-2386 e-mail: [email protected] 152 W ooten Hall Office Hours: 10:00-11:00, 1:00-2:00 MW F TURNITIN.COM: class ID: 9265134 password: mason TEXTS: Tony Saich. 2011. Governance and Politics of China. 3RD EDITION. New York: Palgrave. Peter Hays Gries and Stanley Rosen, eds. 2010. Chinese Politics: State, Society, and the Market. New York: Routledge. Lucian Pye. 1991. China: An Introduction, 4th edition. New York: HarperCollings (photocopied chapters on Blackboard) I. COURSE OBJECTIVES This course is intended to give students an understanding of the political development, political culture, political institutions of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The PRC is the world's most rapidly growing economy. W ith the disintegration of the Soviet Union, it is also now the largest and most powerful Communist Party-ruled nation in the world. Yet the same effort to reform a centralized "command" style economic system that brought about the demise of the Soviet Union was initiated in China in 1978 and has succeeded beyond most people's expectations. At the same time, the post-Mao leadership that has engineered dramatic economic liberalization has resisted pressures to liberalize the political system. The tensions between economic liberalization and political authoritarianism erupted in the Tiananmen Square demonstrations of 1989. W hile similar mass demonstrations in Eastern Europe later that same year resulted in the demise of Communist Party rule there, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) suppressed the social movement of 1989 and preserved the party-state system intact. -

Political Order in Changing Societies

Political Order in Changing Societies by Samuel P. Huntington New Haven and London, Yale University Press Copyright © 1968 by Yale University. Seventh printing, 1973. Designed by John O. C. McCrillis, set in Baskerville type, and printed in the United States of America by The Colonial Press Inc., Clinton, Mass. For Nancy, All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form Timothy, and Nicholas (except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Library of Congress catalog card number: 68-27756 ISBN: 0-300-00584-9 (cloth), 0-300-01171-'7 (paper) Published in Great Britain, Europe, and Africa by Yale University Press, Ltd., London. Distributed in Latin America by Kaiman anti Polon, Inc., New York City; in Australasia and Southeast Asia by John Wiley & Sons Australasia Pty. Ltd., Sidney; in India by UBS Publishers' Distributors Pvt., Ltd., Delhi; in Japan by John Weatherhill, Inc., Tokyo. I·-~· I I. Political Order and Political Decay THE POLITICAL GAP The most important political distinction among countries con i cerns not their form of government but their degree of govern ment. The differences between democracy and dictatorship are less i than the differences between those countries whose politics em , bodies consensus, community, legitimacy, organization, effective ness, stability, and those countries whose politics is deficient in these qualities. Communist totalitarian states and Western liberal .states both belong generally in the category of effective rather than debile political systems. The United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union have different forms of government, but in all three systems the government governs. -

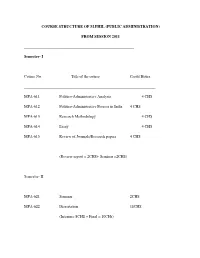

Course Structure of M.Phil (Public Administration)

COURSE STRUCTURE OF M.PHIL (PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION) FROM SESSION 2011 ________________________________________________________ Semester- I Course No. Title of the course Credit Hours ___________________________________________________________________ MPA-611 Politico-Administrative Analysis 4 CHS MPA-612 Politico-Administrative Process in India 4 CHS MPA-613 Research Methodology 4 CHS MPA-614 Essay 4 CHS MPA-615 Review of Journals/Research papers 4 CHS (Review report = 2CHS+ Seminar =2CHS) Semester- II ___________________________________________________________________________ MPA-621 Seminar 2CHS MPA-622 Dissertation 18CHS (Interim= 8CHS + Final = 10CHs) M.PHIL COURSES OF STUDY (Under Semester System) PUBLIC ADMINISTRAION Course No. 611: POLITICO ADMINISTRATIVE ANALYSIS Unit-1 (a) Nature and Scope of Political Analysis: - Approaches – Normative, Legal Institutional, and Behavioural; Traditional Political Analysis versus Modern Political Analysis, Contemporary Trends. (b) Administrative Analysis: - Nature and Scope of Public Administration, New Public Administration. Unit- 2 (a) Theory of Political System for Political Analysis:- System Persistence Model of Easton, System Maintenance Model of Almond. (b) Major Theories for Administrative Analysis:- Mechanistic theory, Human Relation Theory, Bureaucratic Theory, Systems Theory. Unit-3 (a) ‘Political Culture’ as a conceptual tool for Micro and Macro Political Analysis:- Almond’s typology of Political Culture and Patterns Culture Structure Relationship. (b) ‘Administrative Culture’ as a conceptual -

Freedom in the World 1983-1984

Freedom in the World Political Rights and Civil Liberties 1983-1984 A FREEDOM HOUSE BOOK Greenwood Press issues the Freedom House series "Stuthes in Freedom" in addition to the Freedom House yearbook Freedom in the World. Strategies for the 1980s: Lessons of Cuba, Vietnam, and Afghanistan by Philip van Slyck. Stuthes in Freedom, Number 1 Freedom in the World Political Rights and Civil Liberties 1983-1984 Raymond D. Gastil With Essays by William A. Douglas Lucian W. Pye June Teufel Dreyer James D. Seymour Jerome B. Grieder Norris Smith Liang Heng Lawrence R. Sullivan Mab Huang Leonard R. Sussman Peter R. Moody, Jr. Lindsay M. Wright GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London, England Copyright © 1984 by Freedom House, Inc. Freedom House, 20 West 40th Street, New York, New York 10018 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. ISBN: 0-313-23179-6 ISSN: 0732-6610 First published in 1984 Greenwood Press A division of Congressional Information Service, Inc. 88 Post Road West Westport, Connecticut 06881 Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 Contents MAP AND TABLES vii PREFACE ix PART I. THE SURVEY IN 1983 Introduction: Freedom in the Comparative Survey 3 Survey Ratings and Tables for 1983 11 PART II. ANALYZING SPECIFIC ISSUES Another Year of Struggle for Information Freedom Leonard R. Sussman 49 The Future of Democracy: Corporatist or Pluralist Lindsay M. Wright 73 Judging the Health of a Democratic System William A. Douglas 97 PART III. SUPPORTING THE DEVELOPMENT OF DEMOCRACY IN CHINA Foreword 119 Supporting Democracy in the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan): General Considerations for the Freedom House Conference Raymond D. -

Berita Resmi Paten Seri-A

ISSN : 0854-6789 BERITA RESMI PATEN SERI-A No. BRP482/IV/2016 DIUMUMKAN TANGGAL 01 APRIL 2016 s/d 01 OKTOBER 2016 PENGUMUMAN BERLANGSUNG SELAMA 6 (ENAM) BULAN SESUAI DENGAN KETENTUAN PASAL 44 AYAT (1) UNDANG-UNDANG PATEN NOMOR 14 TAHUN 2001 DITERBITKAN BULAN APRIL 2016 DIREKTORAT PATEN, DTLST DAN RD DIREKTORAT JENDERAL KEKAYAAN INTELEKTUAL KEMENTERIAN HUKUM DAN HAK ASASI MANUSIA REPUBLIK INDONESIA BERITA RESMI PATEN SERI-A No. 482 TAHUN 2016 PELINDUNG MENTERI HUKUM DAN HAK ASASI MANUSIA REPUBLIK INDONESIA TIM REDAKSI Penasehat : Direktur Jenderal Kekayaan Intelektual Penanggung jawab : Direktur Paten, DTLST dan RD K e t u a : Kasubdit Permohonan dan Publikasi Paten Sekretaris : Kasi. Publikasi dan Dokumentasi Paten Anggota : Hananto Adi, SH Syahroni., S.Si Ratni Leni Kurniasih Penyelenggara Direktorat Paten, DTLST dan RD Direktorat Jenderal Kekayaan Intelektual Alamat Redaksi dan Tata Usaha Jl. H.R. Rasuna Said Kav. 8-9 Jakarta Selatan 12190 Telepon: (021) 57905611 Faksimili: (021) 57905611 Website : www.dgip.go.id INFORMASI UMUM Berita Resmi Paten Nomor 482 Tahun Ke-26 ini berisi segala kegiatan yang berkaitan dengan pengajuan Permintaan Paten ke Kantor Paten dan memuat lembar halaman pertama (front page) dari dokumen Paten. Daftar Bibliografi yang tertera dalam lembar halaman pertama (front page) adalah sesuai dengan INID Code (Internationally agreed Number of the Identification of Date Code). Penjelasan Nomor Kode pada halaman pertama (front page) Paten adalah sebagai berikut : (11) : Nomor Dokumen (20) : Jenis Publikasi (Paten atau