A TEN YEAR REPORT the Institute of Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

418GBJ Web.Pdf

April 2018 Volume 23, Number 6 From the Executive GEORGIA BAR Director: Website and Directory Enhancements to Benefit Bar Members and the Public Financial Institutions: JOURNAL Protecting Elderly Clients From Financial Exploitation Bending the Arc: Georgia Lawyers in the Pursuit of Social Justice Writing Matters: What e-Filing May Mean to Your Writing 2018 ANNUAL MEETING Amelia Island, Fla. | June 7-10 GEORGIA LAWYERS HELPING LAWYERS Georgia Lawyers Helping Lawyers (LHL) is a new confidential peer-to-peer program that will provide u colleagues who are suffering from stress, depression, addiction or other personal issues in their lives, with a fellow Bar member to be there, listen and help. The program is seeking not only peer volunteers who have experienced particular mental health or substance use u issues, but also those who have experience helping others or just have an interest in extending a helping hand. For more information, visit: www.GeorgiaLHL.org ADMINISTERED BY: DO YOUR EMPLOYEE BENEFITS ADD UP? Finding the right benets provider doesn’t have to be a calculated risk. Our oerings range from Health Coverage to Disability and everything in between. Through us, your rm will have access to unique cost savings opportunities, enrollment technology, HR Tools, and more! The Private Insurance Exchange + Your Firm = Success START SHOPPING THE PRIVATE INSURANCE EXCHANGE TODAY! www.memberbenets.com/gabar OR CALL (800) 282-8626 APRIL 2018 HEADQUARTERS COASTAL GEORGIA OFFICE SOUTH GEORGIA OFFICE 104 Marietta St. NW, Suite 100 18 E. Bay St. 244 E. Second St. (31794) Atlanta, GA 30303 Savannah, GA 31401-1225 P.O. -

Rochester Blue Book 1928

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories V,ZP7. ROCHESTER V^SZ 30GIC Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories NASH-GATES CO. NASH DISTRIBUTORS TWO RETAIL STORES 336 EAST AVENUE 775( CULVER ROAD Phones: Stone 804-805 Phones: Culver 2600-2601 32 (Thestnut Street-' M.D.JEFFREYS -^VOCuC^tCt*;TX.TJ. L. M. WEINER THE SPIRIT OF GOOD SERVICE AND UNEQUALED FACILITIES FOR ITS ACCOMPLISHMENT 2 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories 0 UNION ROCHESTER'S best families for over a quarter of a TRUST century have profitably em ployed tlie service of this COMPANY fifty-million dollar, five-branch, financial institution. Attractive separate depart ments for women. OFFICES Union Trust Building Main St eet at South Avenue Main Street at East Avenue OF Clifford and Joseph Avenues ROCHESTER 4424 Lake Avenue j^+*4^********4-+***+****+*4-+++++*++44'*+****++**-fc*4.*^ (dlfntrp 3Unuimf, 1 ROCHESTER, N,Y Bworattottfl. ijpahttB, Jforttn ani Jfflmuering flanta «S*THpTT,T*,f"f"Wwww**^************^*********^****** * 3 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories |imaiiyMMMMMiu«MM^ Phones: Main 1737-1738 Joseph A. Schantz Co. Furniture, Fire-Proof Storage and Packing of Household Goods AUTO VANS FOR OUT OF TOWN MOVING Office and Salesroom 253 St. Paul, cor. Central Avenue Central Crust Company ROCHESTER, N. Y. The "Friendly" Bank Capital, Surplus and Undivided Profits $1,500,000 Interest Paid on Special Deposits Safe Deposit Boxes for Rent Main Office Brighton Branch 25 MAIN STREET, EAST 1806 EAST AVENUE 4 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories B.FORMAN CD WOMEN'S, GIRLS' and INFANTS' APPAREL AND ALL ACCESSORIES Clinton Avenue South Rochester, N. -

![177] Decentralization Are Implemented and Enduringneighborhood Organization Structures, Social Conditions, and Pol4ical Groundwo](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2150/177-decentralization-are-implemented-and-enduringneighborhood-organization-structures-social-conditions-and-pol4ical-groundwo-192150.webp)

177] Decentralization Are Implemented and Enduringneighborhood Organization Structures, Social Conditions, and Pol4ical Groundwo

DOCUMENT EESU E ED 141 443 UD 017 044 .4 ' AUTHCE Yates, Douglas TITLE Tolitical InnOvation.and Institution-Building: TKe Experience of Decentralization Experiments. INSTITUTION Yale Univ., New Haven, Conn. Inst. fOr Social and Policy Studies. SEPCET NO W3-41 PUB DATE 177] .NCTE , 70p. AVAILABLEFECM Institution for Social and,Policy Studies, Yale tUniversity,-',111 Prospect Street,'New Haven, Conn G6520. FEES PRICE Mt2$0.83 HC-$3.50.Plus Postage. 'DESCEIPTORS .Citizen Participation; City Government; Community Development;,Community Involvement; .*Decentralization; Government Role; *Innovation;. Local. Government; .**Neighborflood; *Organizational Change; Politics; *Power Structure; Public Policy; *Urban Areas ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to resolve what determines the success or failure of innovations in Participatory government; and,-more precisely what are the dynamics of institution-building by which the 'ideas of,participation arid decentralization are implemented and enduringneighborhood institutions aTe established. To answer these questiOns, a number of decentralization experiments were examined to determine which organization structures, Social conditions, and pol4ical arrangements are mcst conducive io.sucCessful innov,ation and institution -building. ThiS inquiry has several theoretical implications:(1) it.examines the nature and utility of pOlitical resources available-to ordinary citizens seeking to influence.their government; 12L it comments on the process of innovation (3) the inquiry addresses ihe yroblem 6f political development, at least as It exists in urban neighborhoods; and (4)it teeks to lay the groundwork fca theory of neighborhood problem-solving and a strategy of reighborhood development. (Author)JM) ****************44**************************************************** -Documents acquired by EEIC,include many Informal unpublished * materials nct available frOm-other sources. ERIC makes every effort * to obtain.the test copy available. -

Panama Treaty 9 77

Collection: Office of the Chief of Staff Files Series: Hamilton Jordan's Confidential Files Folder: Panama Canal Treaty 9/77 Container: 36 Folder Citation: Office of the Chief of Staff Files, Hamilton Jordan's Confidential Files, Panama Canal Treaty 9/77, Container 36 NATIONAL ARCHIVES ANO RECORDSSe'RVIC'E ~~7'",,!:.;, WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIALLlBR~~IESj FORM OF CORRESPONDENTS OR TITLE DATE RESTRICTION DOCUMENT caDle American Imbassy Panama to Secretary of State '/27/77 memo Panama Canal treaty negotiations (S PP.) ca. '/27 A memo aicE Inderfurth to IJ '1'/77 A memo Elmer T. Irooks to ZI '1'/77 A ..,b thomson to 3C ..... ~~ I} ~tI~o '/2'/7~ ...... - ----"------,----,---,-,-,---,- ----'-1---'"--''' FILE LOCATION Chief of Staff (Jordan)/lox , of • (org.)/Panama Canal Treaty~Sept. 1'77 RESTRICTION CODES (A) Closed by Executive Order 12065 governing access to national security information. I B) Closed by statute or by the agency which originated the document. IC) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gift. GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION GSA FORM 7122 (REV. 1-81) MEMORANDUM THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINCTO!': MEMORANDUM TO THE PRESIDENT FROM: HAMILTON JORDAN 1-1.9. DATE: AUGUST 30, 1977 SUBJECT: PANAMA CANAL ENDORSEMENTS 1. The AFL-CIO Executive Council officially adopted :::::',:-·· :.... ·;;h~i: -: a strong statement in favor of the new Panama .~'",. , .:.; Canal Treaties today. Mr. Meany, in a press con ference afterwards, said that the resolution "means full support, using whatever influence we have on Fi· Members of Congress - it certainly means lobbying." In addition, we have a commitment from John Williams, ...... President of the Panama Canal Pilots Association, and from Al Walsh of the Canal Zone AFL-CIO, to testify q~11 ~llli, at Senate hearings that the employee provisions / -~ ... -

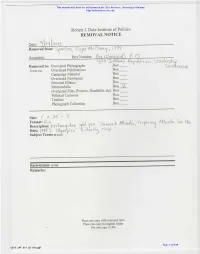

Box Number: M 17 (Otw./R?C<O R 15

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics REMOVAL NOTICE Removed from: S\>QQClt\es, j'Ot1Lt Mc..C.luv\Uj I ( 1 'f<-f Accession: Box Number: m17 (otw./r?C<O r 15 z,cr ~ fftt«r Rt (Jub/t'c CV1 Removed to: Oversized Photographs Box I (Circle one) Oversized Publications Box Campaign Material Box Oversized Newsprint Box Personal Effects Box Mem~rabilia Btm- _:£__ Oversized Flats [Posters, Handbills, etc] Box Political Cartoons Box -- Textiles Box Photograph Collection Box \ ,,,,,,,.... 4" Size: X , 2 5 >< • 7J Format: Pi v'\ Description: Ret k~v\o.>1 Dat~: rn4 > ol ""'~\ t ~', Subject Terms (ifanyJ. Restrictions: none Remarks: Place one copy with removed item Place one copy in original folder File one copy in file Page 1 of 188 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics REMOVAL NOTICE Date: from: ~pe (!c_~J Jt:'~C. e rf)c C..lun ji l'7°1 Accession: Box Number: B 0 ~ \ t ro 'I"' l'l • l 5 6L/ /;;Ff So'"":t-h.v\V"'\ 'R-e._plA l; co-"' ~~~~ Removed to: Oversized Photographs Box C.O~t-('U"UL.. ( C ircle one) Oversized Publications Box Campaign Material Box Oversized Newsprint Box Personal Effects Box Memorabilia -:tJ1f X Oversized Flats [Posters, Handbills, etc] Box __ Political Cartoons Box Textiles Box Photograph Collection Box Restrictions: none Remarks: Place one copy with removed item Place one copy in original folder File one copy in file Page 2 of 188 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu WH"A T , S .INN AT ENGL ..ISH MANOR AND LA.KE .RA.BUN .INNS ..IN 1 994 FOR THOSE OF YOU #HO HAVEN'T BEEN OUR t;UESTS IN THE PAST OR HAVEN'T VISITED US RECENTLY, ENt;LISH ANO I #OULO LIKE TO ACQUAINT YOU ANO BRINE; YOU UP TO DATE. -

Mcintyre V. Ohio Elections Commission: Protecting the Freedom of Speech Or Damaging the Electoral Process?

Catholic University Law Review Volume 46 Issue 2 Winter 1997 Article 7 1997 McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission: Protecting the Freedom of Speech or Damaging the Electoral Process? Rachel J. Grabow Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Rachel J. Grabow, McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission: Protecting the Freedom of Speech or Damaging the Electoral Process?, 46 Cath. U. L. Rev. 565 (1997). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol46/iss2/7 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MCINTYRE v. OHIO ELECTIONS COMMISSION: PROTECTING THE FREEDOM OF SPEECH OR DAMAGING THE ELECTORAL PROCESS? The First Amendment to the United States Constitution establishes the right to freedom of speech.' From its beginning, the United States has encouraged widespread discussion and debate over political issues affect- ing the lives of all citizens and the future course of the country.2 Perhaps 1. See U.S. CONST. amend. I. The First Amendment to the United States Constitu- tion, ratified in 1791, provides: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances." Id. The First Amendment is made applicable to the states by the Fourteenth Amendment. -

Federal-Regulation-Of-Methadone-Treatment.Pdf

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/4899.html We ship printed books within 1 business day; personal PDFs are available immediately. Federal Regulation of Methadone Treatment Richard A. Rettig and Adam Yarmolinsky, Editors; Committee on Federal Regulation of Methadone Treatment, Institute of Medicine ISBN: 0-309-59862-1, 252 pages, 6 x 9, (1995) This PDF is available from the National Academies Press at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/4899.html Visit the National Academies Press online, the authoritative source for all books from the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council: • Download hundreds of free books in PDF • Read thousands of books online for free • Explore our innovative research tools – try the “Research Dashboard” now! • Sign up to be notified when new books are published • Purchase printed books and selected PDF files Thank you for downloading this PDF. If you have comments, questions or just want more information about the books published by the National Academies Press, you may contact our customer service department toll- free at 888-624-8373, visit us online, or send an email to [email protected]. This book plus thousands more are available at http://www.nap.edu. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF File are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Distribution, posting, or copying is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. Request reprint permission for this book. Federal Regulation of Methadone Treatment http://www.nap.edu/catalog/4899.html i Federal Regulation of Methadone Treatment riginal paper book, not from the the authoritative version for attribution. -

Grand Opening of the Sl Green Streetsquash Center

Looking back at our First year in the new building! Summer 2009 11. 20. 2008: GRAND OPENING OF THE SL GREEN STREETSQUASH CENTER Program Director Leah Brown (far left), StreetSquash alum Davian Suckoo (far right), and Hillary Clinton pose with student ambassadors at the opening. What had once been a long-shot dream for a small non-profit was now there for all to see: 8 squash courts, 4 classrooms, a 1,000 square foot library, locker rooms and an office for 14 staff. On a memorable and emotional evening, over 400 people came to see the final product of 5 years of hard work. Almost every person in attendance had in one way or another contributed to the creation of the $9 million SL Green StreetSquash Center. The Grand Opening attracted a wide array of public officials and members of the extended StreetSquash family. In attendance were Hillary Clinton; Shaun Donovan, U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development; Scott Stringer, Manhattan Borough President; and Inez Dickens, NYC Council Member. Several StreetSquash alumni came back from college for the event. Board members brought friends and family. Supporters from Chicago, Boston and Philadelphia made the trip to see, firsthand, what a 19,000 square foot squash and education center looked like. Senator Clinton kicked off the celebration with a rousing speech about the importance of after school programs and the need for everyone to pitch in and make a difference. After having been given a tour of the facility by a few StreetSquashers, she remarked on the amazing opportunities that this Center would provide these students for years to come. -

New Hampshire Road Trip!

JANUARY 2012 Remembering Longtime IOP Advisor Milt Gwirtzman New JFK Jr. Forum Microsite Alumni Q & A with Peter Buttigieg ’04 2012 Polling and Research Careers and Internships New Mayors Conference NEW HAMPSHIRE ROAD TRIP! With the 2012 Republican presidential primary race in high gear this fall, students packed buses to nearby New Hampshire to meet presidential candidates as the IOP conducted timely younger voter public opinion research in Iowa and the Granite State. Welcome to the Institute of Politics at Harvard University Trey Grayson, Director The 2012 election cycle is in high gear, and the past six months have been fast- paced at the Institute. As you will note in this newsletter, the IOP has been at the forefront of election and campaign-related programming, with events, conferences and younger voter research unavailable anywhere else. One of my biggest goals since beginning service as the Institute’s Director has been to improve how the IOP utilizes technology – in an effort to maximize efficiency internally and best distribute and share our content externally to audiences inter- ested in politics and public service. Toward this end, we are very pleased this month to unveil the new online home for John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum programming at www.jfkjrforum.org (see feature on next page). The new microsite not only has a state-of-the art design but also can broadcast Forum programming in a format allowing Forum events to be streamed live or viewed later on any computer or device, including iPads and iPhones. We are also hard at work building a new IOP-wide website – scheduled to be completed next fall – which improves our current website layout and better integrates key online content from Institute students and student publications like the Harvard Political Review. -

Political Development Theory in the Sociological and Political Analyses of the New States

POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT THEORY IN THE SOCIOLOGICAL AND POLITICAL ANALYSES OF THE NEW STATES by ROBERT HARRY JACKSON B.A., University of British Columbia, 1964 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Political Science We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, I966 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission.for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Polit_i_g^j;_s_gience The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date September, 2, 1966 ii ABSTRACT The emergence since World War II of many new states in Asia and Africa has stimulated a renewed interest of sociology and political science in the non-western social and political process and an enhanced concern with the problem of political development in these areas. The source of contemporary concepts of political development can be located in the ideas of the social philosophers of the nineteenth century. Maine, Toennies, Durkheim, and Weber were the first social observers to deal with the phenomena of social and political development in a rigorously analytical manner and their analyses provided contemporary political development theorists with seminal ideas that led to the identification of the major properties of the developed political condition. -

130556 IOP.Qxd

HARVARD UNIVERSITY John F. WINTER 2003 Kennedy School of Message from the Director INSTITUTE Government Spring 2003 Fellows Forum Renaming New Members of Congress OF POLITICS An Intern’s Story Laughter in the Forum: Jon Stewart on Politics and Comedy Welcome to the Institute of Politics at Harvard University D AN G LICKMAN, DIRECTOR The past semester here at the Institute brought lots of excitement—a glance at this newsletter will reveal some of the fine endeavors we’ve undertaken over the past months. But with a new year come new challenges. The November elections saw disturbingly low turnout among young voters, and our own Survey of Student Attitudes revealed widespread political disengagement in American youth. This semester, the Institute of Politics begins its new initiative to stop the cycle of mutual dis- engagement between young people and the world of politics. Young people feel that politicians don’t talk to them; and we don’t. Politicians know that young people don’t vote; and they don’t. The IOP’s new initiative will focus on three key areas: participation and engagement in the 2004 elections; revitalization of civic education in schools; and establishment of a national database of political internships. The students of the IOP are in the initial stages of research to determine the best next steps to implement this new initiative. We have experience To subscribe to the IOP’s registering college students to vote, we have had success mailing list: with our Civics Program, which sends Harvard students Send an email message to: [email protected] into community middle and elementary schools to teach In the body of the message, type: the importance of government and politics. -

Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Political History History 1987 Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963 John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963" (1987). Political History. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_history/3 Divide and Dissent This page intentionally left blank DIVIDE AND DISSENT KENTUCKY POLITICS 1930-1963 JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1987 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2006 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University,Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Qffices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pearce,John Ed. Divide and dissent. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Kentucky-Politics and government-1865-1950.