Where Is the Church of Christ?: the Developing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa was consecrated as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu in Brazil on December !" #$%&" until certain views he expressed about the treatment of the Brazil’s poor, by both the civil (overnment and the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil caused his removal from the Diocese of Botucatu. His Excellency was subsequently named as punishment as *itular bishop of Maurensi by the late Pope Pius +, of the Roman Catholic Church in #$-.. His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord Carlos Duarte Costa had been a strong advocate in the #$-0s for the reform of the Roman Catholic Church" he challenged many of the 1ey issues such as • Divorce" • challenged mandatory celibacy for the clergy, and publicly stated his contempt re(arding. 2*his is not a theological point" but a disciplinary one 3 Even at this moment in time in an interview with 4ermany's Die 6eit magazine the current Bishop of Rome" Pope Francis is considering allowing married priests as was in the old time including lets not forget married bishops and we could quote many Bishops" Cardinals and Popes over the centurys prior to 8atican ,, who was married. • abuses of papal power, including the concept of Papal ,nfallibility, which the bishop considered a mis(uided and false dogma. His Excellency President 4et9lio Dornelles 8argas as1ed the Holy :ee of Rome for the removal of His Excellency Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa from the Diocese of Botucatu. *he 8atican could not do this directly. 1 | P a g e *herefore the Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil entered into an agreement with the :ecretary of the Diocese of Botucatu to obtain the resi(nation of His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord. -

Examining Nostra Aetate After 40 Years: Catholic-Jewish Relations in Our Time / Edited by Anthony J

EXAMINING NOSTRA AETATE AFTER 40 YEARS EXAMINING NOSTRA AETATE AFTER 40 YEARS Catholic-Jewish Relations in Our Time Edited by Anthony J. Cernera SACRED HEART UNIVERSITY PRESS FAIRFIELD, CONNECTICUT 2007 Copyright 2007 by the Sacred Heart University Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, contact the Sacred Heart University Press, 5151 Park Avenue, Fairfield, Connecticut 06825 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Examining Nostra Aetate after 40 Years: Catholic-Jewish Relations in our time / edited by Anthony J. Cernera. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-888112-15-3 1. Judaism–Relations–Catholic Church. 2. Catholic Church– Relations–Judaism. 3. Vatican Council (2nd: 1962-1965). Declaratio de ecclesiae habitudine ad religiones non-Christianas. I. Cernera, Anthony J., 1950- BM535. E936 2007 261.2’6–dc22 2007026523 Contents Preface vii Nostra Aetate Revisited Edward Idris Cardinal Cassidy 1 The Teaching of the Second Vatican Council on Jews and Judaism Lawrence E. Frizzell 35 A Bridge to New Christian-Jewish Understanding: Nostra Aetate at 40 John T. Pawlikowski 57 Progress in Jewish-Christian Dialogue Mordecai Waxman 78 Landmarks and Landmines in Jewish-Christian Relations Judith Hershcopf Banki 95 Catholics and Jews: Twenty Centuries and Counting Eugene Fisher 106 The Center for Christian-Jewish Understanding of Sacred Heart University: -

Events of the Reformation Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution

May 20, 2018 Events of the Reformation Protestants and Roman Catholics agree on first 5 centuries. What changed? Why did some in the Church want reform by the 16th century? Outline Why the Reformation? 1. Church becomes powerful institution. 2. Additional teaching and practices were added. 3. People begin questioning the Church. 4. Martin Luther’s protest. Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution Evidence of Rome’s power grab • In 2nd century we see bishops over regions; people looked to them for guidance. • Around 195AD there was dispute over which day to celebrate Passover (14th Nissan vs. Sunday) • Polycarp said 14th Nissan, but now Victor (Bishop of Rome) liked Sunday. • A council was convened to decide, and they decided on Sunday. • But bishops of Asia continued the Passover on 14th Nissan. • Eusebius wrote what happened next: “Thereupon Victor, who presided over the church at Rome, immediately attempted to cut off from the common unity the parishes of all Asia, with the churches that agreed with them, as heterodox [heretics]; and he wrote letters and declared all the brethren there wholly excommunicate.” (Eus., Hist. eccl. 5.24.9) Everyone started looking to Rome to settle disputes • Rome was always ending up on the winning side in their handling of controversial topics. 1 • So through a combination of the fact that Rome was the most important city in the ancient world and its bishop was always right doctrinally then everyone started looking to Rome. • So Rome took that power and developed it into the Roman Catholic Church by the 600s. Church granted power to rule • Constantine gave the pope power to rule over Italy, Jerusalem, Constantinople and Alexandria. -

The Holy See

The Holy See CARITATIS STUDIUM ENCYCLICAL OF POPE LEO XIII ON THE CHURCH IN SCOTLAND To Our Venerable Brethren, the Archbishops, and Bishops of Scotland. Venerable Brethren, Health and Apostolic Blessing. The ardent charity which renders Us solicitous of Our separated brethren, in nowise permits Us to cease Our efforts to bring back to the embrace of the GoodShepherd those whom manifold error causes to stand aloof from the one Fold ofChrist. Day after day We deplore more deeply the unhappy lot of those who aredeprived of the fullness of the Christian Faith. Wherefore moved by the sense ofthe responsibility which Our most sacred office entails, and by the spirit andgrace of the most loving Saviour of men, Whom We unworthily represent, We areconstantly imploring them to agree at last to restore together with Us thecommunion of the one and the same faith. A momentous work, and of all humanworks the most difficult to be accomplished; one which God's almighty poweralone can effect. But for this very reason We do not lose heart, nor are Wedeterred from Our purpose by the magnitude of the difficulties which cannot beovercome by human power alone. "We preach Christ crucified . and theweakness of God is stronger than men" (1 Cor. i. 23-25). In the midstof so many errors and of so many evils with which We are afflicted orthreatened, We continue to point out whence salvation should be sought,exhorting and admonishing all nations to lift up "their eyes to themountains whence help shall come" (Ps. cxx.). For indeed that which Isaiasspoke in prophecy has been fulfilled, and the Church of God stands forth soconspicuously by its Divine origin and authority that it can be distinguished byall beholders: "And in the last days the mountain of the house of the Lordshall be prepared on the top of mountains and shall be exalted above thehills" (Is. -

Mystici Corporis Christi

MYSTICI CORPORIS CHRISTI ENCYCLICAL OF POPE PIUS XII ON THE MISTICAL BODY OF CHRIST TO OUR VENERABLE BRETHREN, PATRIARCHS, PRIMATES, ARCHBISHOPS, BISHIOPS, AND OTHER LOCAL ORDINARIES ENJOYING PEACE AND COMMUNION WITH THE APOSTOLIC SEE June 29, 1943 Venerable Brethren, Health and Apostolic Benediction. The doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, which is the Church,[1] was first taught us by the Redeemer Himself. Illustrating as it does the great and inestimable privilege of our intimate union with so exalted a Head, this doctrine by its sublime dignity invites all those who are drawn by the Holy Spirit to study it, and gives them, in the truths of which it proposes to the mind, a strong incentive to the performance of such good works as are conformable to its teaching. For this reason, We deem it fitting to speak to you on this subject through this Encyclical Letter, developing and explaining above all, those points which concern the Church Militant. To this We are urged not only by the surpassing grandeur of the subject but also by the circumstances of the present time. 2. For We intend to speak of the riches stored up in this Church which Christ purchased with His own Blood, [2] and whose members glory in a thorn-crowned Head. The fact that they thus glory is a striking proof that the greatest joy and exaltation are born only of suffering, and hence that we should rejoice if we partake of the sufferings of Christ, that when His glory shall be revealed we may also be glad with exceeding joy. -

Catholicism Episode 6

OUTLINE: CATHOLICISM EPISODE 6 I. The Mystery of the Church A. Can you define “Church” in a single sentence? B. The Church is not a human invention; in Christ, “like a sacrament” C. The Church is a Body, a living organism 1. “I am the vine and you are the branches” (Jn. 15) 2. The Mystical Body of Christ (Mystici Corporis Christi, by Pius XII) 3. Jesus to Saul: “Why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9:3-4) 4. Joan of Arc: The Church and Christ are “one thing” II. Ekklesia A. God created the world for communion with him (CCC, par. 760) B. Sin scatters; God gathers 1. God calls man into the unity of his family and household (CCC, par. 1) 2. God calls man out of the world C. The Church takes Christ’s life to the nations 1. Proclamation and evangelization (Lumen Gentium, 33) 2. Renewal of the temporal order (Apostolicam Actuositatem, 13) III. Four Marks of the Church A. One 1. The Church is one because God is One 2. The Church works to unite the world in God 3. The Church works to heal divisions (ecumenism) B. Holy 1. The Church is holy because her Head, Christ, is holy 2. The Church contains sinners, but is herself holy 3. The Church is made holy by God’s grace C. Catholic 1. Kata holos = “according to the whole” 2. The Church is the new Israel, universal 3. The Church transcends cultures, languages, nationalism Catholicism 1 D. Apostolic 1. From the lives, witness, and teachings of the apostles LESSON 6: THE MYSTICAL UNION OF CHRIST 2. -

Nostra Aetate Catholic Church’S Relation with People of Other Religions

259 The Catholic ChNuorscthr’as AJoeutartnee: y into Dialogue Patrick McInerney* The Declaration (NA) is Vatican II’s ground-breaking document on the Nostra Aetate Catholic Church’s relation with people of other religions. 1 The two previous Popes have called it ‘the Magna Carta’ of the Church’s new direction in interreligious dialogue. 2 For centuries church teaching and practice in regard to other religions had been encapsulated in the axiom extra ecclesiam nulla salus (outside the church no salvation). represents a ‘radically new Nostra Aetate understanding of the relations of the church to the other great world religions.’ 3 * Fr Patrick McInerney LSAI, MTheol, PhD is a Columban missionary priest. Assigned to Pakistan for twenty years, he has a licentiate from the in Rome (1986), a Masters in TheologyP foronmtif itchael MInsetlibtuotuer nfoer C thoell Segtued oy fo Df Aivrianbitiyc (a2n0d0 I3s)l aamndic Ps hD from the Australian Catholic University (2009). He is currently Director of the Columban Mission Institute, Coordinator of its and a staff member of its C. e Hnter el efoctru Crehsr iisnt iamni-sMsioulsoligmy Rate ltahteio ns anCde tnhter eB rfork eMn iBssaiyo nIn Sstiutduites’s In C2a0t1h1o lhiec wInassti tauwtea rodfe Sdy dthnee y title of Honorary Fellow of the CAeunsttrrea lfioanr MCiastshiolnic a Undn iCvuerltsuitrye.. He attends interfaith and multi-faith conferences, and gives talks on Islam, Christian-Muslim Relations and Interreligious Relations to a wide variety of audiences. 1. Vatican II, ‘ : Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions,’ inN ostra Aetate Vatican Council I, I:e dT. -

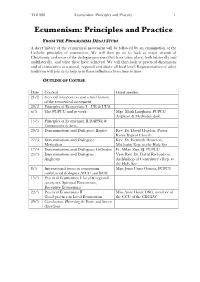

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY the Roman Inquisition and the Crypto

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY The Roman Inquisition and the Crypto-Jews of Spanish Naples, 1569-1582 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Peter Akawie Mazur EVANSTON, ILLINOIS June 2008 2 ABSTRACT The Roman Inquisition and the Crypto-Jews of Spanish Naples, 1569-1582 Peter Akawie Mazur Between 1569 and 1582, the inquisitorial court of the Cardinal Archbishop of Naples undertook a series of trials against a powerful and wealthy group of Spanish immigrants in Naples for judaizing, the practice of Jewish rituals. The immense scale of this campaign and the many complications that resulted render it an exception in comparison to the rest of the judicial activity of the Roman Inquisition during this period. In Naples, judges employed some of the most violent and arbitrary procedures during the very years in which the Roman Inquisition was being remodeled into a more precise judicial system and exchanging the heavy handed methods used to eradicate Protestantism from Italy for more subtle techniques of control. The history of the Neapolitan campaign sheds new light on the history of the Roman Inquisition during the period of its greatest influence over Italian life. Though the tribunal took a place among the premier judicial institutions operating in sixteenth century Europe for its ability to dispense disinterested and objective justice, the chaotic Neapolitan campaign shows that not even a tribunal bearing all of the hallmarks of a modern judicial system-- a professionalized corps of officials, a standardized code of practice, a centralized structure of command, and attention to the rights of defendants-- could remain immune to the strong privatizing tendencies that undermined its ideals. -

Concordia Theological Monthly

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL MONTHLY The Secret of God's Plan HARRY G. COINER The Christ-Figure in Contemporary Literamre DONALD L. DEFFNER Homiletics Theological Observer Book Review VOL. XXXIV May 1963 No.5 BO:)TF T\ T'"t TT"SW All books received in this pe1'iodical may be procured from or through Concordia Pub lishing Hottse, 3558 South Jefferson Avenue. St. Louis 18, Missomi. THE WORLD OF THE VATICAN. By Trinity (misteriosamente emparentada na 01' Robert Neville. New York: Harper and dem da Uniao hipostdtica com toda a Trini Row, c. 1962. 256 pages, plus 16 full dade beatissima)" (Acta Apostolicae Sedis, 38 page plates. Cloth. $4.95. [1946}, 266). In 1954 Pius XII created not Here is a veteran foreign correspondent's "the Feast of Mary of Heaven and Earth" brisk, chatty (sometimes almost gossipy), (p. 77) but the "Feast of Mary the Queen" journalistic chronicle of Vatican City and the (Ad caeli reginam, in Acta .1postolicae Sedis, Holy See from the latter years of the pon 46 [1954}, 638). The Latin formula at the tificate of Pius XII to the threshold of the imposition of the tiara is misspelled and mis Second Vatican Council. The author is the translated on p. 118. There are 379 volumes knowledgeable and experienced former chief (plus indices) in Jacques-Paul Migne's two of the Ti,.>ze-Li!e .i3ure2.ll in Rome; his in Patrologies; f _. work is not "an structive and perceptive book will provide exhaustive anthology[!}" (p.142). On page the reader with valuable background for a 230 "Bishop H"u~ ;:::; :;:'~~j<:" is called Presi better understanding of recent and current dent of the German Lutheran Federation [!l Roman Catholic history. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC JOURNEY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI TO BRAZIL ON THE OCCASION OF THE FIFTH GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE BISHOPS OF LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN MEETING AND CELEBRATION OF VESPERS WITH THE BISHOPS OF BRAZIL ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI Catedral da Sé, São Paulo Friday, 11 May 2007 Dear Brother Bishops! "Although he was the Son of God, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and being made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation to all who obey him." (cf. Heb 5:8-9). 1. The text we have just heard in the Lesson for Vespers contains a profound teaching. Once again we realize that God’s word is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword; it penetrates to the depths of the soul and it grants solace and inspiration to his faithful servants (cf. Heb 4:12). I thank God for the opportunity to be with this distinguished Episcopate, which presides over one of the largest Catholic populations in the world. I greet you with a sense of deep communion and sincere affection, well aware of your devotion to the communities entrusted to your care. The warm reception given to me by the Rector of the Catedral da Sé and by all present has made me feel at home in this great common House which is our Holy Mother, the Catholic Church. 2 I extend a special greeting to the new Officers of the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops and, with gratitude for the kind words of its President, Archbishop Geraldo Lyrio Rocha, I offer prayerful good wishes for his work in deepening communion among the Bishops and in promoting common pastoral activity in a territory of continental dimensions. -

Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology After the Holocaust Carolyn Wesnousky Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College History Honors Papers History Department 2012 “Under the Very Windows of the Pope”: Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology after the Holocaust Carolyn Wesnousky Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/histhp Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wesnousky, Carolyn, "“Under the Very Windows of the Pope”: Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology after the Holocaust" (2012). History Honors Papers. 15. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/histhp/15 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the History Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. “Under the Very Windows of the Pope”: Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology after the Holocaust An Honors Thesis Presented by Carolyn Wesnousky To The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Field Connecticut College New London, Connecticut April 26, 2012 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………...…………..4 Chapter 1: Living in a Christian World......…………………….….……….15 Chapter 2: The Holocaust Comes to Rome…………………...…………….49 Chapter 3: Preparing the Ground for Change………………….…………...68 Chapter 4: Nostra Aetate before the Second Vatican Council……………..95 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………110 Appendix……………………………………………..……………………114 Bibliography………………………………………………………………..117 2 Acknowledgements As much as I would like to claim sole credit for the effort that went into creating this paper, I need to take a moment and thank the people without whom I never would have seen its creation.