Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution Was Also a Radical Educational Institution Modeled After Socialist 1991 36 for This Information, See Ibid., 58

only by rephrasing earlier problems in a new discourse that is unmistakably modern in its premises and sensibilities; even where the answers are old, the questions that produced them have been phrased in the problematic of a new historical situation. The problem was especially acute for the first generation of intellec- Anarchism in the Chinese tuals to become conscious of this new historical situation, who, Revolution as products of a received ethos, had to remake themselves in the very process of reconstituting the problematic of Chinese thought. Anarchism, as we shall see, was a product of this situation. The answers it offered to this new problematic were not just social Arif Dirlik and political but sought to confront in novel ways its demands in their existential totality. At the same time, especially in the case of the first generation of anarchists, these answers were couched in a moral language that rephrased received ethical concepts in a new discourse of modernity. Although this new intellectual problematique is not to be reduced to the problem of national consciousness, that problem was important in its formulation, in two ways. First, essential to the new problematic is the question of China’s place in the world and its relationship to the past, which found expression most concretely in problems created by the new national consciousness. Second, national consciousness raised questions about social relationships, ultimately at the level of the relationship between the individual and society, which were to provide the framework for, and in some ways also contained, the redefinition of even existential questions. -

December 1998

JANUARY - DECEMBER 1998 SOURCE OF REPORT DATE PLACE NAME ALLEGED DS EX 2y OTHER INFORMATION CRIME Hubei Daily (?) 16/02/98 04/01/98 Xiangfan C Si Liyong (34 yrs) E 1 Sentenced to death by the Xiangfan City Hubei P Intermediate People’s Court for the embezzlement of 1,700,00 Yuan (US$20,481,9). Yunnan Police news 06/01/98 Chongqing M Zhang Weijin M 1 1 Sentenced by Chongqing No. 1 Intermediate 31/03/98 People’s Court. It was reported that Zhang Sichuan Legal News Weijin murdered his wife’s lover and one of 08/05/98 the lover’s relatives. Shenzhen Legal Daily 07/01/98 Taizhou C Zhang Yu (25 yrs, teacher) M 1 Zhang Yu was convicted of the murder of his 01/01/99 Zhejiang P girlfriend by the Taizhou City Intermediate People’s Court. It was reported that he had planned to kill both himself and his girlfriend but that the police had intervened before he could kill himself. Law Periodical 19/03/98 07/01/98 Harbin C Jing Anyi (52 yrs, retired F 1 He was reported to have defrauded some 2600 Liaoshen Evening News or 08/01/98 Heilongjiang P teacher) people out of 39 million Yuan 16/03/98 (US$4,698,795), in that he loaned money at Police Weekend News high rates of interest (20%-60% per annum). 09/07/98 Southern Daily 09/01/98 08/01/98 Puning C Shen Guangyu D, G 1 1 Convicted of the murder of three children - Guangdong P Lin Leshan (f) M 1 1 reported to have put rat poison in sugar and 8 unnamed Us 8 8 oatmeal and fed it to the three children of a man with whom she had a property dispute. -

Vol. 14, Spring 2000, No. 1 Judicial Psychiatry in China

COLUMBIA JOURNAL OF ASIAN LAW VOL. 14, SPRING 2000, NO. 1 JUDICIAL PSYCHIATRY IN CHINA AND ITS POLITICAL ABUSES * ROBIN MUNRO I. INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................1 II. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON ETHICAL PSYCHIATRY.......................................6 III. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................10 A. LAW AND PSYCHIATRY PRIOR TO 1949 .......................................................................10 B. THE EARLY YEARS OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC ..........................................................13 C. THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION .....................................................................................22 D. PSYCHIATRIC ABUSE IN THE POST-MAO ERA ..............................................................34 IV. A SHORT GUIDE TO POLITICAL PSYCHOSIS ...............................................................38 A. MANIFESTATIONS OF COUNTERREVOLUTIONARY BEHAVIOR BY THE MENTALLY ILL ...38 B. WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A PARANOIAC AND A POLITICAL DISSIDENT?......40 V. THE LEGAL CONTEXT.......................................................................................................42 A. LEGAL NORMS AND JUDICIAL PROCESS.......................................................................42 B. COUNTERREVOLUTIONARY CRIMES IN CHINA .............................................................50 VI. THE ANKANG: CHINA’S SPECIAL PSYCHIATRIC -

5. Seizing the Power of Ideological “Interpretation”

5. Seizing the Power of Ideological “Interpretation” Materials I. What Did Mao Learn from Stalin’s History of the CPSU? Four years of concerted efforts from 1935 to 1938, Copyrighted with many complications and temporary setbacks along the way,: finally brought Mao on a triumphant march toward realizing his political ideals. By the end of 1938, Mao had control of the Party and thePress Communist armed forces firmly within his grasp, but one matter continued to rankle him—he had yet to seize the power of ideological interpretation. The power of interpretation—theUniversity power to define terminology— is one of the greatest powers available to human beings. Within the Communist Party, the power of interpretation was especially important; whoever was empoweredChinese to interpret the classic texts of Marxism- Leninism controlled the Party’s consciousness. In other words, control over the militaryThe and the Party had to be sustained through the power of ideological interpretation. The importance of interpretation lay not only in the content and the meaning of words and expressions, but even more importantly in integrating these terms with reality, and in the role these terms and concepts played in social existence. Under the long-term management by the Soviet faction, Russified concepts had shrouded the Party in a special spiritual climate and a richly pro-Soviet atmosphere that seriously hindered innovation. In this environment, Wang Ming, Zhang Wentian, and the others in the Soviet faction not only rose to the top but also complacently presented themselves as the bearers of the Holy Grail and lorded themselves over others as the great masters and defenders of the faith, dismissing all innovative thinking as heterodoxy to be eliminated 198 | HOW THE RED SUN ROSE at first instance. -

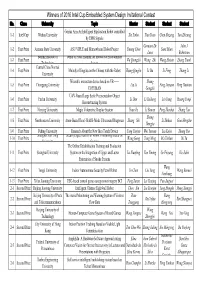

Winners of 2016 Intel Cup Embedded System Design Invitational Contest No

Winners of 2016 Intel Cup Embedded System Design Invitational Contest No. Class University Topic Mentor Student Student Student Genius Arm-An Intelligent Exploration Robot controlled 1-1 Intel Cup Wuhan University Xie Yinbo Tian Yuan Chen Shizeng Yan Zhicong by EMG Signals Gennaro De John J 1-2 First Prize Arizona State University ASU VIPLE and Minnowboard Robot Project Yinong Chen Sami Mian Luca Robertson Beijing Institute of Depth of Field Imaging for Interactive Entertainment 1-3 First Prize Wu Qiongzhi Wang Zhi Wang Haixin Zhang Tianli Technology System Central China Normal 1-4 First Prize Melody of Jingchu on the Chimes with the Robot Zhang Qinglin Li Da Li Feng Zhang Li University Wearable interaction device based on VR—— Zhang 1-5 First Prize Chongqing University Liu Ji Feng Jinyuan Peng Haotian COPYMAN Gengzhi UAV-Based Large Scale Preciseoutdoor Object 1-6 First Prize Fudan University Li Dan Li Ruikang Liu Yang Huang Yanqi Reconstructing System 1-7 First Prize Nanjing University Magic Volumetric Display System Yuan Jie Li Bowen Peng Zhenhui Zhang Yan Zhang 1-8 First Prize Northeastern University Atom-Based Hand-Held B-Mode Ultrasound Diagnoser Zhang Shi Li Zhihua Guo Hengzhe Hongjia 1-9 First Prize Peking University Research About the New Idea Touch Device Yang Yanjun Wei Yuxuan Liu Kefei Zhang Yue Shanghai Jiao Tong Security Specification of Robot Controlling Based On 1-10 First Prize Wang Geng Yang Ming Ma Yichun Di Yu University Gesture The Online Rehabilitation Training and Evaluation 1-11 First Prize Shanghai University -

The Political Trajectories of Chen Duxiu and Qu Qiubai, Two Founding Leaders of the Chinese Communist Party: to Communism and Back Again

THE POLITICAL TRAJECTORIES OF CHEN DUXIU AND QU QIUBAI, TWO FOUNDING LEADERS OF THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY: TO COMMUNISM AND BACK AGAIN A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Kelly Cheung December/2012 Cheung 2 Table of Contents Preface and Introduction 4 List of Abbreviations 9 Names 9 Brief Historiography 10 Biographic Similarities 16 Early Family Life 16 Education and Pre-Marxist Revolutionary Activities 22 Professional Posts 24 The Western-Informed Development of Marxism in Chen Duxiu and Qu Qiubai 27 Introduction 27 Historiography 28 Historical Context – Previous Attempts at Reform in China 30 “What is Marxism?” as Interpreted by Lenin and Stalin 32 Chen and the Deweyan Individual 39 Chen’s Shift From Anti-Traditionalism 42 The West as Interpreted through Dewey and Lenin 44 Dewey’s Lessons on Cultural, Political and Economic Arrangements 48 The Impact of Deweyan Thought on Qu 59 Chen’s Conversion to Marxism and the Role of the Comintern 60 Comintern’s Role in the Rise of the CCP 61 The Peak of Chen’s Marxism 66 Qu Qiubai’s Critical Role in the Chinese Understanding of Marxism 71 Conclusion 75 Shaping the Chinese Literary Revival 77 Introduction 77 Problems of Using Literature as Propaganda 80 The Use and Debate over Western European and Russian Influences 83 Personal Writing Styles 86 The Rise of Anti-Confucianism In The Post-WWI Era 90 The Literary Revolution’s Audience and Enlightened Leader 95 Qu’s Critical Development -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for The

AO 440 (Rev. 06/121 Summons in a Civil Action UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the ,~:&. i+i. el" District of wl~ l &'ic- THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE and NFL PROPERTIES LLC JUDGE SCHOFIELD Plaintiff(s) V. GONG SUNMEI d/b/a NFL-2013. COM; WENG DONG d/b/a NEWYORKGIANTSPROSHOP. COM; SU $572 DANDAN d/b/a NFLGOODSHOP. COM; XIONG JIN CHEN d/b/a NFLNIKEJERSEYSM. COM; MA QIFENG d/b/a —20~~W-JERSEY. 6 Defendant(s) SUMMONS IN A CIVIL ACTION To: (Defendant 's name and address) See Rider A for a Complete Listing of Defendants and Defendants' Addresses A lawsuit has been filed against you. Within 21 days after service of this summons on you (not counting the day you received it) —or 60 days if you are the United States or a United States agency, or an officer or employee of the United States described in Fed. R. Civ. P. 12 (a)(2) or (3) —you must serve on the plaintiff an answer to the attached complaint or a motion under Rule 12 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The answer or motion must be served on the plaintiff or plaintiff's attorney, whose name and address are: Bradley I. Ruskin Proskauer Rose LLP Eleven Times Square New York, NY 10036 If you fail to respond, judgment by default will be entered against you for the relief demanded in the complaint. You also must file your answer or motion with the court. CLERK OF COL%i Date: Signature of Cleric or Deputy ClerIc AO 440 (Rev. -

The Esa Learneo! Project for Stimulating Earth Observation

IGARSS 2013 – 2013 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium Melbourne, Australia 21 – 26 July 2013 Pages 1-770 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP13IGA-POD ISBN: 978-1-4799-1112-7 1/6 TABLE OF CONTENTS MO3.101: EDUCATION AND REMOTE SENSING MO3.101.1: THE ESA LEARNEO! PROJECT FOR STIMULATING EARTH OBSERVATION ....................................... 1 EDUCATION Fabio Del Frate, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy; Pierre-Philippe Mathieu, European Space Agency, Italy; Valborg Byfield, Chris Banks, National Oceanography Centre, United Kingdom; Malcolm Dobson, Bilko Develoment Limited, United Kingdom; Matteo Picchiani, GEO-K srl, Italy; Vinca Rosmorduc, Collecte Localisation Satellites, France MO3.101.2: THE LINKAGES BETWEEN STEM EDUCATION AND HOMELAND SECURITY ..................................... 5 SCIENCES AND MANAGEMENT Delandria Jones, Jaclyn P. Kuzniar, Alcorn State University, United States; TeAmbreya Moore, NCCC Southern Region and FEMA, United States; Sam Nwaneri, Alcorn State University, United States MO3.101.3: SOFTWARE ENVIRONMENTS FOR ATMOSPHERIC LIDAR REMOTE SENSING ................................... 9 Nimmi C. P. Sharma, Central Connecticut State University, United States; Jo Ann Parikh, Southern Connecticut State University, United States MO3.102: EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL GEOSCIENCE AND REMOTE SENSING MO3.102.2: THE INFLUENCE OF ORGANIC MATTER ON SOIL DIELECTRIC CONSTANT AT ............................. 13 MICROWAVE FREQUENCIES (0.5-40GHZ) Jun Liu, Shaojie Zhao, Lingmei Jiang, Linna Chai, Fengmin Wu, Beijing Normal University, -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMÏ RED GENESIS: THE HUNAN FIRST NORMAL SCHOOL AND THE CREATION OF CHINESE COMÜNISM, 1903-1921 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Liyan Liu, B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2001 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor James R. -

Dangerous Minds

DANGEROUS MINDS Political Psychiatry in China Today and its Origins in the Mao Era Human Rights Watch and Geneva Initiative on Psychiatry Copyright © August 2002 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-278-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2002109978 Cover photo: Inside the Tianjin Ankang institute for mentally disordered offenders. There is no credit/copyright for anonymity reasons. Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 500, Washington, D.C. 20009 Tel: (202) 612-4321, Fax: (202) 612-4333, E-mail: [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, Second Floor, London N1 9FP, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail: [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the Human Rights Watch news e-mail list, send a blank e-mail message to [email protected]. Addresses for Geneva Initiative on Psychiatry P.O. Box 2182 1200 BG Hilversum, The Netherlands Tel.: (31) 35 6838727, Fax (31) 35 6833646, E-mail [email protected] Zenevos Iniciatyva Psichiatrijoje Oginskio 3, 2040 Vilnius, Lithuania Tel: 00370-2-715760, Fax: 00370-2-715761, E-mail: [email protected] Zhenevska Iniciativa v Psihiatriata 1, Maliovitsa Str., Sofia 1000, Bulgaria Tel/fax:+359 2 987 78 75, E-mail:[email protected] HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. -

Reflections on Enlightenment from Multiple Perspectives

Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series III, Asian Philosophical Studies, Volume 36 Reflections on Enlightenment from Multiple Perspectives Edited by Wang Xingfu, Zou Shipeng & Zhang Shuangli The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2019 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Gibbons Hall B-20 620 Michigan Avenue, NE Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Names: Wang, Xingfu, 1954- editor. Title: Reflections on enlightenment from multiple perspectives / edited by Wang Xingfu, Zou Shipeng & Zhang Shuangli. Description: first [edition]. | Washington, DC : Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, 2019. | Series: Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series III, East Asian philosophical studies ; Volume 36 | Series: Chinese philosophical studies ; 36 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019008007 | ISBN 9781565183407 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Enlightenment--China. | Philosophy, Chinese. | Philosophy and religion--China. Classification: LCC B5233.E55 R44 2019 | DDC 181/.11--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019008007 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Wang Xingfu Part I. Modernization and Enlightenment in China 1. On Enlightenment Thinking and the Construction of 19 Chinese Culture Today Yu Wujin 2. A Critique of Modernity and the “Dialectic of Enlightenment” 37 Wu Xiaoming 3. China at the Great Turning Point Again: 45 Enlightenment from “Western Marxism” Chen Xueming 4. “Myth Is Already Enlightenment, and Enlightenment 51 Reverts to Mythology”: On the Enlightenment Spirit from the Perspective of Dialectic of Enlightenment Wang Fengcai 5. Karl-Otto Apel and the Enlightenment 63 Luo Yaling Part II. Rethinking Marxism in Contemporary China 6. -

Zhang Wentian and the Academy of Marxism and Leninism

Zhang Wentian and The Academy of Marxism and Leninism During the pre-Rectification Period, 1938-1941 by Yoel Kornreich B.A., University of Toronto, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSiTY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) February 2009 © Yoel Komreich, 2009 ABSTRACT This thesis on Zhang Wentian (1900-1976) and the Academy of Marxism and Leninism (1938-1941) in pre-Rectification Yan’an has two primary objectives. First, contrary to previous studies of Yan’an, which engaged in Mao’s rise to power, this study examines the period from the perspective of another senior Party leader Zhang Wentian. This study seeks to explore Zhang’s background, his political position at the Party, his relationship with Mao, and the ideological differences and compatibilities between him and Mao. It argues that Zhang was among Mao’s supporters and that he shared with him many ideas. In spite of their collaboration, Zhang and Mao had some major ideological disagreements regarding the sinification of Marxism and Party history. Through the analysis of Zhang Wentian, this thesis is intended to help “rescue” CCP history from the Maoist narrative. Second, this thesis explores diversity in pre-Rectification Yan’ an through the study of the Academy of Marxism and Leninism where Zhang Wentian served as the principal. The examination of the Academy shows that the lecturers there held contending positions regarding the sinification of Marxim and the periodization of Chinese history, and that Party leaders of different political factions were able to lecture at the Academy.