Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2010 Report Annual Museum the Palace of the Forbidden City Publishing House City Publishing the Forbidden

Annual Report Annual Annual Report 2010 of The Palace Museum The Forbidden City Publishing House 2010 of The Palace Museum The Palace of The Forbidden City Publishing House City Publishing The Forbidden 定价: 68.00元 Annual Report 2010 of The Palace Museum Annual Report 2010 of The Palace Museum Director: Zheng Xinmiao Executive Deputy Director: Li Ji Deputy Directors: Li Wenru, Ji Tianbin, Wang Yamin, Chen Lihua, Song Jirong, Feng Nai’en ※Address: No. 4 Jingshan qianjie, Beijing ※Postal code: 100009 ※Website: http://www.dpm.org.cn Contents Work in the Year 2010 8 Collection Management and Conservation of Ancient Buildings 12 Exhibitions 24 Academic Research and Publication 42 Education and Public Outreach 54 The Digital Palace Museum 62 Cooperation and Exchange 68 Financial Statements 82 Work in the Year 2010 n 2010, the Palace Museum took advantage of the occasions of celebrat- Iing the 85th anniversary of the founding of the Palace Museum and the 590th anniversary of the construction of the Forbidden City, involved itself in such undertakings as public security and services, preservation of col- lection and ancient buildings, exhibition and display, academic research & publication, information system construction, overseas exchange and coop- eration, and made more contributions to the sustainable development of its cultural heritage. Held activities to celebrate the 85th anniversary of the Palace Mu- seum and the 590th anniversary of the construction of the Forbidden City; Received 12.83 million visitors and took measures to ensure their -

Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution Was Also a Radical Educational Institution Modeled After Socialist 1991 36 for This Information, See Ibid., 58

only by rephrasing earlier problems in a new discourse that is unmistakably modern in its premises and sensibilities; even where the answers are old, the questions that produced them have been phrased in the problematic of a new historical situation. The problem was especially acute for the first generation of intellec- Anarchism in the Chinese tuals to become conscious of this new historical situation, who, Revolution as products of a received ethos, had to remake themselves in the very process of reconstituting the problematic of Chinese thought. Anarchism, as we shall see, was a product of this situation. The answers it offered to this new problematic were not just social Arif Dirlik and political but sought to confront in novel ways its demands in their existential totality. At the same time, especially in the case of the first generation of anarchists, these answers were couched in a moral language that rephrased received ethical concepts in a new discourse of modernity. Although this new intellectual problematique is not to be reduced to the problem of national consciousness, that problem was important in its formulation, in two ways. First, essential to the new problematic is the question of China’s place in the world and its relationship to the past, which found expression most concretely in problems created by the new national consciousness. Second, national consciousness raised questions about social relationships, ultimately at the level of the relationship between the individual and society, which were to provide the framework for, and in some ways also contained, the redefinition of even existential questions. -

Lecture Notes, by James Cahill

Lecture Notes, by James Cahill Note: The image numbers in these lecture notes do not exactly coincide with the images onscreen but are meant to be reference points in the lectures’ progression. Lecture: Addendum 1A: Freer Medal Acceptance Address On November 18, 2010, I was in Washington DC at the Freer Gallery of Art, where I started out my career as a Chinese art specialist sixty years ago. This time it was to receive the Charles Lang Freer Medal, which is given intermittently since 1956 to honor notable scholars of Asian art. Photo: James Cahill and Julian Raby, director of the Freer I will be the twelfth recipient, the sixth for Chinese art. The ones in Chinese art before me begin with Osvald Siren, someone I have a great admiration for. But the others are my teachers and my heroes: Laurence Sickman, Max Loehr, Alexander Soper, and Sherman Lee. Photos: front and back of bronze Freer Medal, designed by Paul Manship [Begins reading lecture] If this prose sounds familiar, it is because I wrote the English version of Yukio Yashiro’s 1965 acceptance speech. He was the third recipient of the Freer Medal. 1950 (exactly 60 years ago): had finished a B.A. in Oriental Languages at UC Berkeley and, on the advice of my teacher, Edward Schafer, applied for and received the Louise Wallace Hackney Scholarship for cataloguing Chinese paintings at the Freer. I worked with Archibald Wenley, the director of the Freer at the time. 1951–1953: M.A. program at University of Michigan, studied under Max Loehr. -

Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution

the only proper object of revolutionary discourse. In doing so, anarchists opened up a perspective on revolution that was foreclosed by the political and suppressed even in the think- ing of revolutionaries, who insisted on a social revolution but could not conceive of the social apart from the political tasks Anarchism in the Chinese of revolution. To affirm the fundamental significance of anar- Revolution chism in revolutionary discourse is not to privilege anarchism per se, but to reaffirm the indispensability of an antipolitical conception of society in raising fundamental questions about the nature of domination and oppression, which are otherwise Arif Dirlik excluded from both the analysis of ideology and historical anal- ysis in general. In declaring politics—all politics, including rev- olutionary politics—to be inimical to the cause of an authen- tic social revolution, anarchists pointed to the politicization of the social as an ideological closure that not only disguised the fact that revolutionary hegemony itself presupposed a struc- ture of authority that contradicted its own goals, but also cov- ered up areas of social oppression that were not immediately visible in the realm of politics (the family and gender oppres- sion were their primary concerns). More fundamental anar- chists explained that the revolutionary urge to restore politi- cal order was a consequence of the naturalization of politics— the inability, therefore, to imagine society without politics—as one of the most deeply ingrained ideological habits that per- petuated relations of domination in society. The explanation moved them past the realm of ideology to the realm of social discourses as the location for habits of authority and submis- sion that sustained both political and social oppression. -

December 1998

JANUARY - DECEMBER 1998 SOURCE OF REPORT DATE PLACE NAME ALLEGED DS EX 2y OTHER INFORMATION CRIME Hubei Daily (?) 16/02/98 04/01/98 Xiangfan C Si Liyong (34 yrs) E 1 Sentenced to death by the Xiangfan City Hubei P Intermediate People’s Court for the embezzlement of 1,700,00 Yuan (US$20,481,9). Yunnan Police news 06/01/98 Chongqing M Zhang Weijin M 1 1 Sentenced by Chongqing No. 1 Intermediate 31/03/98 People’s Court. It was reported that Zhang Sichuan Legal News Weijin murdered his wife’s lover and one of 08/05/98 the lover’s relatives. Shenzhen Legal Daily 07/01/98 Taizhou C Zhang Yu (25 yrs, teacher) M 1 Zhang Yu was convicted of the murder of his 01/01/99 Zhejiang P girlfriend by the Taizhou City Intermediate People’s Court. It was reported that he had planned to kill both himself and his girlfriend but that the police had intervened before he could kill himself. Law Periodical 19/03/98 07/01/98 Harbin C Jing Anyi (52 yrs, retired F 1 He was reported to have defrauded some 2600 Liaoshen Evening News or 08/01/98 Heilongjiang P teacher) people out of 39 million Yuan 16/03/98 (US$4,698,795), in that he loaned money at Police Weekend News high rates of interest (20%-60% per annum). 09/07/98 Southern Daily 09/01/98 08/01/98 Puning C Shen Guangyu D, G 1 1 Convicted of the murder of three children - Guangdong P Lin Leshan (f) M 1 1 reported to have put rat poison in sugar and 8 unnamed Us 8 8 oatmeal and fed it to the three children of a man with whom she had a property dispute. -

Vol. 14, Spring 2000, No. 1 Judicial Psychiatry in China

COLUMBIA JOURNAL OF ASIAN LAW VOL. 14, SPRING 2000, NO. 1 JUDICIAL PSYCHIATRY IN CHINA AND ITS POLITICAL ABUSES * ROBIN MUNRO I. INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................1 II. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON ETHICAL PSYCHIATRY.......................................6 III. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................10 A. LAW AND PSYCHIATRY PRIOR TO 1949 .......................................................................10 B. THE EARLY YEARS OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC ..........................................................13 C. THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION .....................................................................................22 D. PSYCHIATRIC ABUSE IN THE POST-MAO ERA ..............................................................34 IV. A SHORT GUIDE TO POLITICAL PSYCHOSIS ...............................................................38 A. MANIFESTATIONS OF COUNTERREVOLUTIONARY BEHAVIOR BY THE MENTALLY ILL ...38 B. WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A PARANOIAC AND A POLITICAL DISSIDENT?......40 V. THE LEGAL CONTEXT.......................................................................................................42 A. LEGAL NORMS AND JUDICIAL PROCESS.......................................................................42 B. COUNTERREVOLUTIONARY CRIMES IN CHINA .............................................................50 VI. THE ANKANG: CHINA’S SPECIAL PSYCHIATRIC -

Red Scarf Girl

A Facing History and Ourselves Study Guide Teaching RED SCARF GIRL Created to Accompany the Memoir Red Scarf Girl, by Ji-li Jiang A Facing History and Ourselves Study Guide Teaching RED SCARF GIRL Created to Accompany the Memoir Red Scarf Girl, by Ji-li Jiang Facing History and Ourselves is an international educational and professional development organization whose mission is to engage students of diverse backgrounds in an examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism in order to promote the development of a more humane and informed citizenry. By studying the historical development of the Holocaust and other examples of genocide, students make the essential connection between history and the moral choices they confront in their own lives. For more information about Facing History and Ourselves, please visit our website at www.facinghistory.org. The front cover illustration is a section from a propaganda poster created during the beginning of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1968), the same years Ji-li describes in her memoir. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China 1949, government and party officials used mass- produced posters as a way to promote nationalism and convey the values of the Communist Party. Propaganda posters were especially important during the Cultural Revolution, and this poster represents many dominant themes of this media: the glorification of Mao, the color red symbolizing China and the Chinese Communist Party, and the depiction of youth as foot-soldiers for the revolution. The slogan on the poster expresses a popular anthem of the era: Chairman Mao is the Reddest Reddest Red Sun in Our Hearts. -

5. Seizing the Power of Ideological “Interpretation”

5. Seizing the Power of Ideological “Interpretation” Materials I. What Did Mao Learn from Stalin’s History of the CPSU? Four years of concerted efforts from 1935 to 1938, Copyrighted with many complications and temporary setbacks along the way,: finally brought Mao on a triumphant march toward realizing his political ideals. By the end of 1938, Mao had control of the Party and thePress Communist armed forces firmly within his grasp, but one matter continued to rankle him—he had yet to seize the power of ideological interpretation. The power of interpretation—theUniversity power to define terminology— is one of the greatest powers available to human beings. Within the Communist Party, the power of interpretation was especially important; whoever was empoweredChinese to interpret the classic texts of Marxism- Leninism controlled the Party’s consciousness. In other words, control over the militaryThe and the Party had to be sustained through the power of ideological interpretation. The importance of interpretation lay not only in the content and the meaning of words and expressions, but even more importantly in integrating these terms with reality, and in the role these terms and concepts played in social existence. Under the long-term management by the Soviet faction, Russified concepts had shrouded the Party in a special spiritual climate and a richly pro-Soviet atmosphere that seriously hindered innovation. In this environment, Wang Ming, Zhang Wentian, and the others in the Soviet faction not only rose to the top but also complacently presented themselves as the bearers of the Holy Grail and lorded themselves over others as the great masters and defenders of the faith, dismissing all innovative thinking as heterodoxy to be eliminated 198 | HOW THE RED SUN ROSE at first instance. -

![3607 Erligang [BMF 9-26].Indd 11 1/2/14 9:52 AM Its Subsequent Excavation by Li Ji in the 1930S Shaped Interpretations of the Origin of Civilization in China](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1011/3607-erligang-bmf-9-26-indd-11-1-2-14-9-52-am-its-subsequent-excavation-by-li-ji-in-the-1930s-shaped-interpretations-of-the-origin-of-civilization-in-china-2251011.webp)

3607 Erligang [BMF 9-26].Indd 11 1/2/14 9:52 AM Its Subsequent Excavation by Li Ji in the 1930S Shaped Interpretations of the Origin of Civilization in China

Preface when i began to organize the conference that led to this volume, one of my first tasks was to design a mission statement that would explain to participants and to our general audience what the conference would be about and what we hoped to accomplish. The goals it sets forth are shared by this book: Named after a type site discovered in Zhengzhou in 1951, the Erligang civ- ilization arose in the Yellow River valley around the middle of the second millennium bce. Shortly thereafter, its distinctive elite material culture spread to a large part of China’s Central Plain, in the south reaching as far as the banks of the Yangzi River. Source of most of the cultural achieve- ments familiarly associated with the more famous Anyang site, the Erli- gang culture is best known for the Zhengzhou remains, a smaller city at Panlongcheng in Hubei, and a large- scale bronze industry of remarkable artistic and technological sophistication. Bronzes are the hallmark of Erli- gang elite material culture. They are also the archaeologist’s main evidence for understanding the transmission of bronze metallurgy to the cultures of southern China. This conference brings together scholars from a variety of disciplines to explore what is known about the Erligang culture and its art, its spectacular bronze industry in particular. Participants will ask how the Erligang artistic and technological tradition was formed and how we should understand its legacy to the later cultures of north and south China. Comparison with other ancient civilizations will afford an important perspective. To the goals stated above may be added one more—to bring the Erligang civili- zation to the attention of a wider audience. -

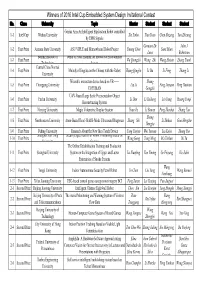

Winners of 2016 Intel Cup Embedded System Design Invitational Contest No

Winners of 2016 Intel Cup Embedded System Design Invitational Contest No. Class University Topic Mentor Student Student Student Genius Arm-An Intelligent Exploration Robot controlled 1-1 Intel Cup Wuhan University Xie Yinbo Tian Yuan Chen Shizeng Yan Zhicong by EMG Signals Gennaro De John J 1-2 First Prize Arizona State University ASU VIPLE and Minnowboard Robot Project Yinong Chen Sami Mian Luca Robertson Beijing Institute of Depth of Field Imaging for Interactive Entertainment 1-3 First Prize Wu Qiongzhi Wang Zhi Wang Haixin Zhang Tianli Technology System Central China Normal 1-4 First Prize Melody of Jingchu on the Chimes with the Robot Zhang Qinglin Li Da Li Feng Zhang Li University Wearable interaction device based on VR—— Zhang 1-5 First Prize Chongqing University Liu Ji Feng Jinyuan Peng Haotian COPYMAN Gengzhi UAV-Based Large Scale Preciseoutdoor Object 1-6 First Prize Fudan University Li Dan Li Ruikang Liu Yang Huang Yanqi Reconstructing System 1-7 First Prize Nanjing University Magic Volumetric Display System Yuan Jie Li Bowen Peng Zhenhui Zhang Yan Zhang 1-8 First Prize Northeastern University Atom-Based Hand-Held B-Mode Ultrasound Diagnoser Zhang Shi Li Zhihua Guo Hengzhe Hongjia 1-9 First Prize Peking University Research About the New Idea Touch Device Yang Yanjun Wei Yuxuan Liu Kefei Zhang Yue Shanghai Jiao Tong Security Specification of Robot Controlling Based On 1-10 First Prize Wang Geng Yang Ming Ma Yichun Di Yu University Gesture The Online Rehabilitation Training and Evaluation 1-11 First Prize Shanghai University -

Why Were Chang'an and Beijing So Different? Author(S): Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol

Why Were Chang'an and Beijing so Different? Author(s): Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 45, No. 4 (Dec., 1986), pp. 339-357 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/990206 Accessed: 07-04-2016 18:13 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians This content downloaded from 78.108.103.216 on Thu, 07 Apr 2016 18:13:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Why Were Chang'an and Beijing So Different? NANCY SHATZMAN STEINHARDT University of Pennsylvania Historians of premodern Chinese urbanism have long assumed that After stating the hypothesis of three lineages of Chinese imperial the origins of the Chinese imperial city plan stem from a passage in city building, the paper illustrates and briefly comments on the key the Kaogong Ji (Record of Trades) section of the classical text Rit- examples of each city type through history. -

Inside the Forbidden City

Inside the “Forbidden City” Academic exchange between Palace Museum, China and KCHR, India Oct. 7th to 30th, 2016 (Report of themeetings, excavation, archaeo-science learning, field explorations, museum and institutional visits etc) P J Cherian, Preeta Nayar, Deepak Nair, Tathagata Neogi, Dineesh Krishnan, Renuka T. P The Palace Museum Kerala Council for Historical Research 4 Jingshan Qianjie, PB No. 839, Vyloppilly Samskrithi Bhavan, Beijing 100009, China Nalanda, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala 695003, India Inside the “Forbidden City” Edited by Professor P. J. Cherian Published by © KCHR, PB No.839, Vyloppilly Samskrithi Bhavan, Nalanda Thiruvananthapuram, PIN. 695 003. 2016 Layout and cover page design Jishnu S Chandran Cover page painting “Damo the sage crossing the stream of life on a reed” the untitled painting by Emperor Chenghua. Damo was a Buddhist monk believed to have reached China around 5th c CE from south-west coast of peninsular India (Kerala) and became an influential thinker in Chinese history. One lore says he hails from the Thalassery region of North Kerala and his original name was Damodaran. The photo and title of the painting is by PJC. KCHR hopes to track his trail and vision of life through research with support from Chinese colleagues and Palace Museum ISBN 8185499432 The KCHR, chaired by Professor K N Panikkar, is an autonomous research institute funded by the Higher Education Department, Government of Kerala. Affiliated to the University of Kerala, it has bilateral academic and exchange agreements with various universities and research institutes in India and abroad. All rights reserved. Citation only with permission, No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior permission of the publisher.