Copyright by Lei Guo 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of Wang Wei (Ca

_full_journalsubtitle: International Journal of Chinese Studies/Revue Internationale de Sinologie _full_abbrevjournaltitle: TPAO _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 0082-5433 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1568-5322 (online version) _full_issue: 5-6_full_issuetitle: 0 _full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien J2 voor dit article en vul alleen 0 in hierna): Sufeng Xu _full_alt_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, hier invullen): The Courtesan as Famous Scholar _full_is_advance_article: 0 _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 _full_alt_articletitle_toc: 0 T’OUNG PAO The Courtesan as Famous Scholar T’oung Pao 105 (2019) 587-630 www.brill.com/tpao 587 The Courtesan as Famous Scholar: The Case of Wang Wei (ca. 1598-ca. 1647) Sufeng Xu University of Ottawa Recent scholarship has paid special attention to late Ming courtesans as a social and cultural phenomenon. Scholars have rediscovered the many roles that courtesans played and recognized their significance in the creation of a unique cultural atmosphere in the late Ming literati world.1 However, there has been a tendency to situate the flourishing of late Ming courtesan culture within the mainstream Confucian tradition, assuming that “the late Ming courtesan” continued to be “integral to the operation of the civil-service examination, the process that re- produced the empire’s political and cultural elites,” as was the case in earlier dynasties, such as the Tang.2 This assumption has suggested a division between the world of the Chinese courtesan whose primary clientele continued to be constituted by scholar-officials until the eight- eenth century and that of her Japanese counterpart whose rise in the mid- seventeenth century was due to the decline of elitist samurai- 1) For important studies on late Ming high courtesan culture, see Kang-i Sun Chang, The Late Ming Poet Ch’en Tzu-lung: Crises of Love and Loyalism (New Haven: Yale Univ. -

2020 Annual Report

2020 ANNUAL REPORT About IHV The Institute of Human Virology (IHV) is the first center in the United States—perhaps the world— to combine the disciplines of basic science, epidemiology and clinical research in a concerted effort to speed the discovery of diagnostics and therapeutics for a wide variety of chronic and deadly viral and immune disorders—most notably HIV, the cause of AIDS. Formed in 1996 as a partnership between the State of Maryland, the City of Baltimore, the University System of Maryland and the University of Maryland Medical System, IHV is an institute of the University of Maryland School of Medicine and is home to some of the most globally-recognized and world- renowned experts in the field of human virology. IHV was co-founded by Robert Gallo, MD, director of the of the IHV, William Blattner, MD, retired since 2016 and formerly associate director of the IHV and director of IHV’s Division of Epidemiology and Prevention and Robert Redfield, MD, resigned in March 2018 to become director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and formerly associate director of the IHV and director of IHV’s Division of Clinical Care and Research. In addition to the two Divisions mentioned, IHV is also comprised of the Infectious Agents and Cancer Division, Vaccine Research Division, Immunotherapy Division, a Center for International Health, Education & Biosecurity, and four Scientific Core Facilities. The Institute, with its various laboratory and patient care facilities, is uniquely housed in a 250,000-square-foot building located in the center of Baltimore and our nation’s HIV/AIDS pandemic. -

The Morpho-Syntax of Aspect in Xiāng Chinese

, 7+(0253+26<17$;2)$63(&7,1 ;,Ɩ1*&+,1(6( ,, 3XEOLVKHGE\ /27 SKRQH 7UDQV -.8WUHFKW HPDLOORW#XXQO 7KH1HWKHUODQGV KWWSZZZORWVFKRROQO ,6%1 185 &RS\ULJKW/X0DQ$OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG ,,, 7+(0253+26<17$;2)$63(&7 ,1;,Ɩ1*&+,1(6( 352()6&+5,)7 7(59(5.5,-*,1*9$1 '(*5$$'9$1'2&725$$1'(81,9(56,7(,7/(,'(1 23*(=$*9$1'(5(&7250$*1,),&86352)05&--0672/.(5 92/*(16+(7%(6/8,79$1+(7&2//(*(9225352027,(6 7(9(5'(',*(123'21'(5'$*6(37(0%(5 ./2..( '225 0$1/8 *(%25(17(<8(<$1*&+,1$ ,1 ,9 3URPRWRU 3URIGU53(6\EHVPD &RSURPRWRU 'U$./LSWiN 3URPRWLHFRPPLVVLH 3URIGU-6'RHWMHV 3URIGU'+ROH 8QLYHUVLWlW6WXWWJDUW 'U+6XQ 8QLYHUVLWpGH3LFDUGLH-XOHV9HUQH$PLHQV 9 7DEOHRI&RQWHQWV .H\WRDEEUHYLDWLRQV ,; $FNQRZOHGJHPHQWV ;, &KDSWHU ,QWURGXFWLRQ %DVLFLQWURGXFWLRQ 7KHODQJXDJHLWVVSHDNHUVDQGLWVPDMRUSURSHUWLHV 3UHYLRXVOLQJXLVWLFVWXGLHVRQ;LƗQJ $LPRIWKHGLVVHUWDWLRQ 7KHRUHWLFDOEDFNJURXQG 7HQVHLQ0DQGDULQ $VSHFW 9LHZSRLQWDVSHFWLQ0DQGDULQ 6LWXDWLRQDVSHFWVHPDQWLFVDQGV\QWD[ ,QQHUDVSHFWLQ0DQGDULQ 7HOLFLW\LQ0DQGDULQ 6XPPDU\RI&KDSWHU 2YHUYLHZRIWKHWKHVLV 6XPPDU\RIWKHIROORZLQJFKDSWHUV &KDSWHU 9 ta ,QWURGXFWLRQ taDVDSHUIHFWLYHPDUNHUDQGRUDSURJUHVVLYHPDUNHU taDVDSHUIHFWLYHPDUNHU taDVDSURJUHVVLYHPDUNHU taZLWKQHJDWLRQ taZLWKPDQQHUDGYHUELDOV taZLWKWKHSURJUHVVLYHPDUNHU tsaiko taZLWKVHQWHQFHILQDO tsaiko ta D SHUIHFWLYH RU D GXUDWLYH PDUNHU ta ZLWK holding YHUEV 6XPPDU\ /LWHUDWXUHLQWURGXFWLRQ ta DV D FRPSOHWLYH RU D SURJUHVVLYHGXUDWLYH PDUNHUD FDVHRIRYHUODS taDVDWUDQVLWLRQPDUNHU 9, 7DEOHRI&RQWHQWV -

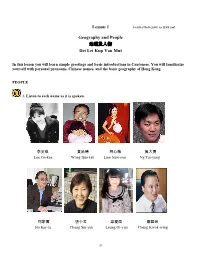

Lesson 1 VALIDATION COPY 1.0 JUNE 2007

Lesson 1 VALIDATION COPY 1.0 JUNE 2007 Geography and People 地理及人物 Dei Lei Kup Yan Mut In this lesson you will learn simple greetings and basic introductions in Cantonese. You will familiarize yourself with personal pronouns, Chinese names, and the basic geography of Hong Kong. PEOPLE 1. Listen to each name as it is spoken. 李安琪 黄品德 林心薇 吴大勇 Lee On-kee Wong Bun-tak Lum Sum-mei Ng Tai-yung 何家富 張小玉 梁爱茵 鄭国荣 Ho Kar-fu Chang Siu-yuk Leung Oi-yun Cheng Kwok-wing 20 2. Listen to these simple greetings and phrases. Hello, Hi 你好,哈囉, 喂!/喂? nei ho, ha lo, wai!/wai? Good morning 早晨 jo sun Good afternoon 午安 ngo on Good evening 晚安 maan on Good night 早唞 jo tau How are you? 你好嗎? nei ho ma? What’s up? 點呀? dim ah? Have you eaten yet? 食咗飯未呀? sik jo fan mei? How are you lately? 你近來點呀? 最近點呀? nei gan loi dim aa? What a coincidence/to see you 乜ロ甘啱 吖? mat kam ngaam ah? Long time no see 好耐冇見 ho noi mo gin Fine, Very well 好,非常好 ho, fei sheung ho Very good 好好 ho ho Quite good 幾好 gei ho Not quite good 唔係幾好 ng hei gei ho Take care 保重,慢慢行 bo chung, man man haang See you tomorrow 聽日見 ting yat gin See you later 遲啲見, 一陣見 chi di gin, yat jun gin That’s it for now 係ロ甘先啦! hai kam sin la Talk to you later 第日再傾 dai yat joi ken Good-bye 再見,拜拜 joi gin, baai baai Thank you 多謝晒,唔該晒 do je saai, ngo goi saai Please… 唔該… ng goi… You’re welcome 唔駛客氣, ng sai haak hei 唔駛唔該 ng sai ng goi Sorry 對唔住 dui ng jiu Excuse me 唔好意思 ng ho yi si No way! 唔得! ng dak! Nice to meet you. -

Monitoring Complex Supply Chains by Lei Liu a Dissertation Presented In

Monitoring Complex Supply Chains by Lei Liu A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved April 2015 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: George Runger, Chair Esma Gel Mani Janakiram Rong Pan ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2015 ABSTRACT The complexity of supply chains (SC) has grown rapidly in recent years, resulting in an increased difficulty to evaluate and visualize performance. Consequently, analytical approaches to evaluate SC performance in near real time relative to targets and plans are important to detect and react to deviations in order to prevent major disruptions. Manufacturing anomalies, inaccurate forecasts, and other problems can lead to SC disruptions. Traditional monitoring methods are not sufficient in this respect, because com- plex SCs feature changes in manufacturing tasks (dynamic complexity) and carry a large number of stock keeping units (detail complexity). Problems are easily confounded with normal system variations. Motivated by these real challenges faced by modern SC, new surveillance solutions are proposed to detect system deviations that could lead to disruptions in a complex SC. To address supply-side deviations, the fitness of different statistics that can be extracted from the enterprise resource planning system is evaluated. A monitoring strategy is first proposed for SCs featuring high levels of dynamic complexity. This presents an opportunity for monitoring methods to be applied in a new, rich domain of SC management. Then a monitoring strategy, called Heat Map Contrasts (HMC), which converts monitoring into a series of classification problems, is used to monitor SCs with both high levels of dynamic and detail complexities. -

Misterfengshui.Com 風水先生

misterfengshui.com 風水先生 Do you know that Chinese surnames (last name) totaled 10,129? According to The Greater China Surname’s Dictionary, compiled by Chan Lik Pu over a 30-year period of work since 1960. Among them, 8,000 surnames were from Han’s race while approximately 2,000 were minorities. In today’s China, approximately 3,000 Han’s surnames are still around. Top Ten Surnames In Beijing (total surnames 2,225) 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 王 李 張 劉 趙 楊 陳 徐 馬 吳 Wang Li Zhang Liu Zhao Yang Chen Xu Ma Wu (10.6% ) (9.6%) (9.6%) (7.7% ) Approx. 5% Approx. 5% Approx. 4% Approx. 4% Approx. 4% Approx. 3% Top Ten Surnames In Taiwan (total surnames 1,694) 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 陳 林 黃 張 李 王 吳 劉 蔡 楊 Chen Lin Huang Zhang Li Wang Wux. Liu Cai Yang Approx .7% Approx 6 % Approx 6 % Approx 6 % Approx. 5% Approx 5 % Approx 4 % Approx 4 % Approx 4 % Approx 4 % Below is the table of most popular surnames (top 100) in China according to China Population Statistic: The top 20 accounted for more than half of Chinese population while the top 100 accounted for 87% of Chinese populations. Rank Surname Rank Rank Surname Rank Surname Rank Surname 1st 李 Li 2nd 王 Wang 3rd 張 Zhang 4th 劉 Liu 5th 陳 Chen Rank Surname Rank Rank Surname Rank Surname Rank Surname 6th 楊 Yang 7th 趙 Zhao 8th 黃 Huang 9th 周 Zhou 10 th 吳 Wu Rank Surname Rank Rank Surname Rank Surname Rank Surname 11th 徐 Xu 12th 孫 Sun 13th 胡 Hu 14th 朱 Zhu 15 th 高 Gao Rank Surname Rank Rank Surname Rank Surname Rank Surname 16th 林 Lin 17th 何 He 18th 郭 Guo 19th 馬 Ma 20 th 羅 Luo Rank -

Representing Talented Women in Eighteenth-Century Chinese Painting: Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instruction at the Lake Pavilion

REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION By Copyright 2016 Janet C. Chen Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler ________________________________ Amy McNair ________________________________ Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Jungsil Jenny Lee ________________________________ Keith McMahon Date Defended: May 13, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Janet C. Chen certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler Date approved: May 13, 2016 ii Abstract As the first comprehensive art-historical study of the Qing poet Yuan Mei (1716–97) and the female intellectuals in his circle, this dissertation examines the depictions of these women in an eighteenth-century handscroll, Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instructions at the Lake Pavilion, related paintings, and the accompanying inscriptions. Created when an increasing number of women turned to the scholarly arts, in particular painting and poetry, these paintings documented the more receptive attitude of literati toward talented women and their support in the social and artistic lives of female intellectuals. These pictures show the women cultivating themselves through literati activities and poetic meditation in nature or gardens, common tropes in portraits of male scholars. The predominantly male patrons, painters, and colophon authors all took part in the formation of the women’s public identities as poets and artists; the first two determined the visual representations, and the third, through writings, confirmed and elaborated on the designated identities. -

Directors and Senior Management

DIRECTORS AND SENIOR MANAGEMENT GENERAL The following table sets out certain information in respect of our directors and senior management: Year of Position(s)/roles and Date of joining Name Age responsibilities appointment our Group Directors Richard Qiangdong Liu (劉強東) ........... 47 Chairman of the Board of January 2007 2004 Directors and Chief Executive Officer Martin Chi Ping Lau (劉熾平) .............. 47 Director March 2014 2014 Ming Huang ............................ 56 Independent Director March 2014 2014 Louis T. Hsieh .......................... 55 Independent Director May 2014 2014 Dingbo Xu (許定波)...................... 57 Independent Director May 2018 2018 Senior Management Lei Xu (徐雷)........................... 45 Chief Executive Officer of September 2009 JD Retail 2019 Zhenhui Wang (王振輝)................... 45 Chief Executive Officer of April 2017 2010 JD Logistics Sandy Ran Xu (許冉)..................... 43 Chief Financial Officer June 2020 2018 Yayun Li (李婭雲) ....................... 39 Chief Compliance Officer January 2017 2007 Directors The board currently consists of five directors, including three independent directors. See “—Board Practices” for the functions and duties of the Board. In addition, the Board is responsible for exercising other powers, functions and duties in accordance with the Articles of Association, and all applicable laws and regulations, including the Hong Kong Listing Rules. Richard Qiangdong Liu (劉強東) has been our chairman and chief executive officer since our inception. Mr. Liu has over 20 years of experience in the retail and e-commerce industries. In June 1998, Mr. Liu started his own business in Beijing, which was mainly engaged in the distribution of magneto-optical products. In January 2004, Mr. Liu launched his first online retail website. He founded our business later that year and has guided our development and growth since then. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI" ARGUMENT STRUCTURE, HPSG, AND CHINESE GRAMMAR DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Qian Gao, B.A., M.A. ******* The Ohio State University 2001 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Carl J. Pollard, Adviser Professor Peter W. -

A Study of Xu Xu's Ghost Love and Its Three Film Adaptations THESIS

Allegories and Appropriations of the ―Ghost‖: A Study of Xu Xu‘s Ghost Love and Its Three Film Adaptations THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Qin Chen Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Master's Examination Committee: Kirk Denton, Advisor Patricia Sieber Copyright by Qin Chen 2010 Abstract This thesis is a comparative study of Xu Xu‘s (1908-1980) novella Ghost Love (1937) and three film adaptations made in 1941, 1956 and 1995. As one of the most popular writers during the Republican period, Xu Xu is famous for fiction characterized by a cosmopolitan atmosphere, exoticism, and recounting fantastic encounters. Ghost Love, his first well-known work, presents the traditional narrative of ―a man encountering a female ghost,‖ but also embodies serious psychological, philosophical, and even political meanings. The approach applied to this thesis is semiotic and focuses on how each text reflects the particular reality and ethos of its time. In other words, in analyzing how Xu‘s original text and the three film adaptations present the same ―ghost story,‖ as well as different allegories hidden behind their appropriations of the image of the ―ghost,‖ the thesis seeks to broaden our understanding of the history, society, and culture of some eventful periods in twentieth-century China—prewar Shanghai (Chapter 1), wartime Shanghai (Chapter 2), post-war Hong Kong (Chapter 3) and post-Mao mainland (Chapter 4). ii Dedication To my parents and my husband, Zhang Boying iii Acknowledgments This thesis owes a good deal to the DEALL teachers and mentors who have taught and helped me during the past two years at The Ohio State University, particularly my advisor, Dr. -

A Guide to Names and Naming Practices

March 2006 AA GGUUIIDDEE TTOO NN AAMMEESS AANNDD NNAAMMIINNGG PPRRAACCTTIICCEESS This guide has been produced by the United Kingdom to aid with difficulties that are commonly encountered with names from around the globe. Interpol believes that member countries may find this guide useful when dealing with names from unfamiliar countries or regions. Interpol is keen to provide feedback to the authors and at the same time develop this guidance further for Interpol member countries to work towards standardisation for translation, data transmission and data entry. The General Secretariat encourages all member countries to take advantage of this document and provide feedback and, if necessary, updates or corrections in order to have the most up to date and accurate document possible. A GUIDE TO NAMES AND NAMING PRACTICES 1. Names are a valuable source of information. They can indicate gender, marital status, birthplace, nationality, ethnicity, religion, and position within a family or even within a society. However, naming practices vary enormously across the globe. The aim of this guide is to identify the knowledge that can be gained from names about their holders and to help overcome difficulties that are commonly encountered with names of foreign origin. 2. The sections of the guide are governed by nationality and/or ethnicity, depending on the influencing factor upon the naming practice, such as religion, language or geography. Inevitably, this guide is not exhaustive and any feedback or suggestions for additional sections will be welcomed. How to use this guide 4. Each section offers structured guidance on the following: a. typical components of a name: e.g. -

Accepted Manuscript These Authors Contributed Equally As Joint Senior Authors

Tenofovir Alafenamide to Prevent Perinatal Hepatitis B Transmission: A Multicenter, Prospective, Observational Study Qing-Lei Zeng,1,a, * Zu-Jiang Yu,1, a, * Fanpu Ji,2,a Guang-Ming Li,3 Guo-Fan Zhang,4 Jiang-Hai Xu,5 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciaa1939/6062485 by Jules Levin on 10 January 2021 Zhi-Min Chen,6 Guang-Lin Cui,7 Wei Li,8 Da-Wei Zhang,9 Juan Li,1 Jun Lv,1 Zhi-Qin Li,1 Hong-Xia Liang,1 Chang-Yu Sun,1 Ya-Jie Pan,1 Yan-Min Liu,1 and Fu-Sheng Wang9,* 1Department of Infectious Diseases and Hepatology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan, China, 2Department of Infectious Diseases, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China, 3Department of Hepatology, The Sixth People’s Hospital of Zhengzhou City, Zhengzhou, Henan, China, 4Department of Infectious Diseases, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanyang Medical College, Nanyang, Henan, China, 5Department of Hepatology, The Fifth People’s Hospital of Anyang City, Anyang, Henan, China, 6Department of Obstetrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan, China, 7Department of Clinical Laboratory, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan, China, 8Department of Infectious Diseases, Henan Provincial People’s Hospital, Zhengzhou, Henan, China, and 9Treatment and Research Center for Infectious Diseases, The Fifth Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, National Clinical Research Center for Infectious Diseases, Beijing, China aThese authors contributed equally as joint first authors. * Accepted Manuscript These authors contributed equally as joint senior authors.