Mapping the Destruction of Urban Japan During World War II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections and 1Rememb Irancees

DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution IJnlimiter' The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II REFLECTIONS AND 1REMEMB IRANCEES Veterans of die United States Army Air Forces Reminisce about World War II Edited by William T. Y'Blood, Jacob Neufeld, and Mary Lee Jefferson •9.RCEAIR ueulm PROGRAM 2000 20050429 011 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved I OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of Information Is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 2000 na/ 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Reflections and Rememberances: Veterans of the US Army Air Forces n/a Reminisce about WWII 5b. GRANT NUMBER n/a 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER n/a 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Y'Blood, William T.; Neufeld, Jacob; and Jefferson, Mary Lee, editors. -

Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University

INCENDIARY WARS: The Transformation of United States Air Force Bombing Policy in the WWII Pacific Theater Gilad Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University Faculty Advisor: Professor Mark Mazower Second Reader: Professor Alan Brinkley INCENDIARY WARS 1 Note to the Reader: For the purposes of this essay, I have tried to adhere to a few conventions to make the reading easier. When referring specifically to a country’s aerial military organization, I capitalize the name Air Force. Otherwise, when simply discussing the concept in the abstract, I write it as the lower case air force. In accordance with military standards, I also capitalize the entire name of all code names for operations (OPERATION MATTERHORN or MATTERHORN). Air Force’s names are written out (Twentieth Air Force), the bomber commands are written in Roman numerals (XX Bomber Command, or simply XX), while combat groups are given Arabic numerals (305th Bomber Group). As the story shifts to the Mariana Islands, Twentieth Air Force and XXI Bomber Command are used interchangeably. Throughout, the acronyms USAAF and AAF are used to refer to the United States Army Air Force, while the abbreviation of Air Force as “AF” is used only in relation to a numbered Air Force (e.g. Eighth AF). Table of Contents: Introduction 3 Part I: The (Practical) Prophets 15 Part II: Early Operations Against Japan 43 Part III: The Road to MEETINGHOUSE 70 Appendix 107 Bibliography 108 INCENDIARY WARS 2 Introduction Curtis LeMay sat awake with his trademark cigar hanging loosely from his pursed ever-scowling lips (a symptom of his Bell’s Palsy, not his demeanor), with two things on his mind. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

The US Army Air Forces in WWII

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES AIR FORCE Air Force Historical Studies Office 28 June 2011 Errata Sheet for the Air Force History and Museum Program publication: With Courage: the United States Army Air Forces in WWII, 1994, by Bernard C. Nalty, John F. Shiner, and George M. Watson. Page 215 Correct: Second Lieutenant Lloyd D. Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 218 Correct Lieutenant Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 357 Correct Hughes, Lloyd D., 215, 218 To: Hughes, Lloyd H., 215, 218 Foreword In the last decade of the twentieth century, the United States Air Force commemorates two significant benchmarks in its heritage. The first is the occasion for the publication of this book, a tribute to the men and women who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War 11. The four years between 1991 and 1995 mark the fiftieth anniversary cycle of events in which the nation raised and trained an air armada and com- mitted it to operations on a scale unknown to that time. With Courage: U.S.Army Air Forces in World War ZZ retells the story of sacrifice, valor, and achievements in air campaigns against tough, determined adversaries. It describes the development of a uniquely American doctrine for the application of air power against an opponent's key industries and centers of national life, a doctrine whose legacy today is the Global Reach - Global Power strategic planning framework of the modern U.S. Air Force. The narrative integrates aspects of strategic intelligence, logistics, technology, and leadership to offer a full yet concise account of the contributions of American air power to victory in that war. -

Civil Defense and Chemical Warfare in Great Britain, 1915-1945 Jordan I

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-7-2018 Britain Can Take It: Civil Defense and Chemical Warfare in Great Britain, 1915-1945 Jordan I. Malfoy [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC006585 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Malfoy, Jordan I., "Britain Can Take It: Civil Defense and Chemical Warfare in Great Britain, 1915-1945" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3639. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3639 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida BRITAIN CAN TAKE IT: CHEMICAL WARFARE AND THE ORIGINS OF CIVIL DEFENSE IN GREAT BRITAIN, 1915 - 1945 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Jordan Malfoy 2018 To: Dean John F. Stack, Jr. choose the name of dean of your college/school Green School of International and Public Affairs choose the name of your college/school This disserta tion, writte n by Jordan Malfoy, and entitled Britain Can Take It: Chemical Warfare and the Ori gins of Civil D efense i n Great Britain, 1915-1945, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

Sgoth Quartermaster Company (Cam

SGOth Quartermaster Company (Cam. 174th Replacement Company, Army Alr posite). Forces (Provisional) . 3BOth Station Hospital. 374th Service Squadron. 36lst Coast Artlllery Transport Detach. 374th Trwp Carrier Group, Headqllar- ment. ters. 36lst Station Hospital. 375th Troop Carrier Omup, Headquar- 3626 Coast Artillery Transport De ter& tachxnent 376th Serviee Squabon. 362d Quartermaster Service Company. 377th Quartermaster Truck Company. 3E2d Station Hospital. 378th Medical Service Detachment. 3636 Coast Artillery Transport Detach 380th Bombardment Group (Heavy), ment Headquarters. 3638 Station Hospital. B82d Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic 364th Coast Artillery Transport Detach Weapons Battalion. ment. 383d Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic 364th Station Hospital. Weapons Battalion. 365th Coast Artillery Transport Detach 383d Avintion-Squadron. ment. 3&?d Medical Service @ompany. 365th Harbor Craft Company, Trans 383d Quartermaster Truck Company. portation Coma 384th Quartermaster Truck Company. 366th Coast Artillery Transport Detach 385th Medical Servlce Detachment. ment 380th Service Squadron. mth Harbor Craft Company. Trans 387th Port Battalion, Transportation portation Corps. Corps. Headqunrters and Headquar- 367th Coast Artillery Transport Detach ters Detachment. ment 388th Service squadron. 367th Harbor Craft Company, Trans 389th Antiaircrnft Artlllery Automatic portation Cams. Weapons Battalion. 868th Harbor Craft Company, Trans 380th Quartermaster Truck Company. portation Corps. 389th Servlce Squadron. 36Qth Harbor Crnft Company, -

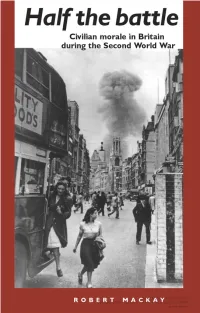

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM Via Free Access HALF the BATTLE

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access HALF THE BATTLE Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 1 16/09/02, 09:21 Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 2 16/09/02, 09:21 HALF THE BATTLE Civilian morale in Britain during the Second World War ROBERT MACKAY Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 3 16/09/02, 09:21 Copyright © Robert Mackay 2002 The right of Robert Mackay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 5893 7 hardback 0 7190 5894 5 paperback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs. -

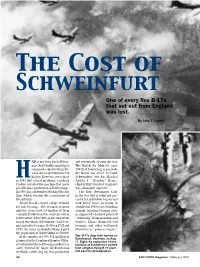

The Cost of H

The Cost of Schweinfurt One of every five B-17s that set out from England was lost. By John T. Correll ad it not been for ball bear- and potentially shorten the war. ings, Schweinfurt might have The British Air Ministry since remained a small town in Ba- 1943 had been trying to persuade varia and escaped the notice of the Royal Air Force to bomb history. However, it was there Schwein furt, but Air Marshal in 1883 that a local mechanic, Friedrich Arthur T. “Bomber” Harris, HFischer, invented the machine that made chief of RAF Bomber Command, possible mass production of ball bearings. was adamantly opposed. In 1906, his son founded the Kugelfischer The RAF determined early firm, which became the cornerstone of in the war that it could not pre- the industry. cisely hit individual targets and World War II created a huge demand took heavy losses in trying. It for ball bearings. The German aviation switched in 1942 to area bombing industry alone used 2.4 million of them at night, targeting German cities a month. Production was concentrated in in support of a national policy of Schweinfurt, where five plants turned out “dehousing” German citizens and nearly two-thirds of Germany’s ball bear- workers. Harris dismissed ball ings and roller bearings. Between 1922 and bearings and other bottleneck 1943, the surge in manufacturing tripled objectives as “panacea targets.” the population of Schweinfurt to 50,000. In the summer of 1943, US and British Top: B-17s drop their bombs on Schweinfurt, Germany, on Aug. planners for the Combined Bomber Offen- 17. -

Strategic Bombing, the Nuclear Revolution, and City Busting

STRATEGIC BOMBING, THE NUCLEAR REVOLUTION, AND CITY BUSTING A presentation by Henry Sokolski Executive Director Nonproliferation Policy Education Center www.npolicy.org The Institute of World Politics June 11, 2013 1 QUESTIONS TO BE ANSWERED I. How was city busting viewed and done before and during WWII? II. The nuclear weapons revolution: How militarily significant was it? III. Why, initially, did developing ever larger nuclear weapons seem logical? IV. Precision Guidance: How did its advent constitute a counter revolution and how has it affected nuclear weapons deployments? V. City busting: Why might its morality still be an issue today? 6/11/2013 2 UNTIL MODERNITY, TARGETING CITIES WAS FROWNED UPON Sun Tzu, The Art of War, 500 BC “To subdue the enemy without fighting is the supreme excellence. Thus, what is of supreme importance in war is to attack the enemy’s strategy. Next best is to disrupt his alliances by diplomacy. The next best is to attack his army. And the worst policy is to attack cities.” 3 SHERMAN’S MARCH TO THE SEA: PRECURSOR TO CITY BUSTING 4 Atlanta, Georgia AMERICAN CIVIL WAR Field Artillery and Fire A six-month campaign Few if any civilians killed Residences, churches, and hospitals spared 5 FRENCH SUBMARINE WARFARE THEORY: FIRST MODERN MUSINGS ON STRATEGIC WEAPONRY 6 FRENCH HOPED SUBMARINES MIGHT HELP NEUTRALIZE UK & ITS FLEET BY BLOCKADE Gymnote class Narval 7 Gustave Zede class Sirene class EVEN UNRESTRICTED SUB WARFARE IN WWI, THOUGH, HAD MIXED RESULTS 8 WORLD WAR I TRENCH WARFARE: ITS HORRORS REKINDLED INTEREST -

So, 391--G2, 394; in First World War 378; Anti-Submarine Weapons 378

Index 1053 So, 391--g2, 394; in First World War 378; Baker fitted to Lancaster x 758; Rose anti-submarine weapons 378--g, 393-4; U 685, 752-3; Village Inn/AGLT and radar boat losses 378-9, 394-5, 396, 399, 405, assisted gun-laying 752-3, 823; need to 414, 416; Allied shipping losses 379, 405, counter Schrage Musik fitted to German 414; U-boat tactics 381 , 391 , 396, 404- 5, night-fighters 687-8, 734, 763-4, 830, 854 409, 412; Mooring patrols 383, 402-4, Army Co-operation Command, see 410-1 l; Leigh Light 393- 4, 395; Biscay commands offensive 393-8; ASV radar and counter Army Photo Interpretation Section: and measures, 393- 4, 395; Musketry patrols procedures for photographic 397-8, 446; Percussion operations 398; in reconnaissance 296-7 Operation Overlord 406-ro; inshore Arnhem 326, 347-8, 875-6, 881 - 3, 890 patrols 410-16; Sir Arthur Harris believes Arnold, Gen. H.H. 832 bomber offensive is more important 598, Arnold-Portal-Towers agreement: and supply 638; Portal agrees 620; Bomber Command of bomber aircraft 599 ordered to attack U-boat bases in France Arras 775, 808 638--g, 677; other refs 95, 270, 375 Article xv, see Canadianization Anti-U-boat Warfare Committee 391 , 394 Ash, P/O W.F. 207 Antwerp 327, 337, 835, 845, 855 Ashford, F/L Herbert 648 Anzio 287-8 Ashman, W/C R.A. 400 Aqualagna 308 Assam 876, 905 Arakan 901, 903, 906 Associated Press 71 Archer, w/c J.C. 398, 400 ASV , see radar, air-to-surface vessel (ASV) Archer, F/L P.L.I. -

Hitting Home the Air Offensive Against Japan

The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II Hitting Home The Air Offensive Against Japan Daniel L. Haulman AIR FORCE HISTORY AND MUSEUMS PROGRAM 1999 Hitting Home The Air Offensive Against Japan The strategic bombardment of Japan during World War II remains one of the most controversial subjects of military history because it involved the first and only use of atomic weapons in war. It also raised the question of whether strategic bombing alone can win wars, a question that dominated U.S. Air Force thinking for a generation. Without question, the strategic bombing of Japan contributed very heavily to the Japanese decision to surrender. The United States and her allies did not have to invade the home islands, an invasion that would have cost many thousands of lives on both sides. This pamphlet traces the development of the bombing of the Japan- ese home islands, from the modest but dramatic Doolittle raid on Tokyo in April 1942, through the effort to bomb from bases in China that were supplied by airlift over the Himalayas, to the huge 500-plane raids from the Marianas in the Pacific. The campaign changed from precision daylight bombing to night incendiary bombing of Japanese cities and ultimately to the use of atomic bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The story covers the debut of the spectacular B–29 air- craft—in many ways the most awesome weapon of World War II— and its use not only as a bomber but also as a mine-layer. Hitting Home is the sequel to High Road to Tokyo Bay, a pamphlet by the same author that concentrated on Army Air Forces’ tactical op- erations in Asia and the Pacific areas during World War II. -

West Field, Tinian, Marianas Islands Xxi Bomber

The Story of The “Billy Mitchell Group” 468 H-Bomb Group – From the C.B.I. to the Marianas 276 WEST FIELD, TINIAN, MARIANAS ISLANDS XXIST BOMBER COMMAND JUNE 1945 THE BIG PUSH IS ON THE WAY © 2008 New England Air Museum. All rights reserved. The Story of The “Billy Mitchell Group” 468 H-Bomb Group – From the C.B.I. to the Marianas 277 468TH BOMBARDMENT GROUP (VH) - JUNE 1945 June was the anniversary month for the 468th Bomb Group. On 5 June 1944 the first B-29 mission flown was directed at Bangkok, Thailand. June 15th of that year, the Group took part in another, more important “first” – the first land based mission against the Japanese home islands. Amongst those of us that are still here with the Group, the twelve succeeding months have been long, hard, and eventful. Thousands of words have been written during the year. The story of America’s new weapon, the B-29 Superfortress, the beginning of the assault on Japan, the longest bombing raids in history, and the new “Global Air Force.” One could go on forever, yet not capture the true meaning behind all of these. Underneath the pretty word picture was the blood and guts spilled, making the project a huge success. Further there was sweat, labor and red tape. Also to be found were good men and bad, efficient and inefficient. Somehow this heterogeneous mass congealed, and in so doing, brought forth the finished product – the most potent striking force in the Air Force today. The finest illustration can be found in the records of the Group’s June operations, which follow.