Hitting Home the Air Offensive Against Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Study North Field Historic District

Tinian National Historical ParkStudy Page 1 of 26 SPECIAL STUDY NORTH FIELD HISTORIC DISTRICT Tinian Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands September 2001 United States Department of the Interior - National Park Service http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/Tinian/tiniandr.htm 4/9/2008 Tinian National Historical ParkStudy Page 2 of 26 http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/Tinian/tiniandr.htm 4/9/2008 Tinian National Historical ParkStudy Page 3 of 26 North Field as it looked during World War II. The photo shows only three runways, which dates it sometime earlier than May 1945 when construction of Runway Four was completed. North Field was designed for an entire wing of B-29 Superfortresses, the 313th Bombardment Wing, with hardstands to park 265 B-29s. Each of the parallel runways stretched more than a mile and a half in length. Around and between the runways were nearly eleven miles of taxiways. Table of Contents SUMMARY BACKGROUND DESCRIPTION OF THE STUDY AREA Location, Size and Ownership Regional Context RESOURCE SIGNIFICANCE Current Status of the Study Area Cultural Resources Natural Resources Evaluation of Significance EVALUATION OF SUITABILITY AND FEASIBILITY Rarity of This Type of Resource (Suitability) Feasibility for Protection Position of CNMI and Local Government Officials http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/Tinian/tiniandr.htm 4/9/2008 Tinian National Historical ParkStudy Page 4 of 26 Plans and Objectives of the Lease Holder FINDINGS, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Findings and Conclusions Recommendations APPENDIX Selected References CINCPACFLT Letter of July 26, 2000 COMNAVMAR Letter of August 28, 2001 Brochure: Self-Guided Tour of North Field Tinian Interpret Marianas Campaign from American Memorial Park, on Tinian, and with NPS Publications MAPS Figure 1. -

WINTER 2013 - Volume 60, Number 4 the Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A

WINTER 2013 - Volume 60, Number 4 WWW.AFHISTORICALFOUNDATION.ORG The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

Adam of Bremen on Slavic Religion

Chapter 3 Adam of Bremen on Slavic Religion 1 Introduction: Adam of Bremen and His Work “A. minimus sanctae Bremensis ecclesiae canonicus”1 – in this humble manner, Adam of Bremen introduced himself on the pages of Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum, yet his name did not sink into oblivion. We know it thanks to a chronicler, Helmold of Bosau,2 who had a very high opinion of the Master of Bremen’s work, and after nearly a century decided to follow it as a model. Scholarship has awarded Adam of Bremen not only with a significant place among 11th-c. writers, but also in the whole period of the Latin Middle Ages.3 The historiographic genre of his work, a history of a bishopric, was devel- oped on a larger scale only after the end of the famous conflict on investiture between the papacy and the empire. The very appearance of this trend in histo- riography was a result of an increase in institutional subjectivity of the particu- lar Church.4 In the case of the environment of the cathedral in Bremen, one can even say that this phenomenon could be observed at least half a century 1 Adam, [Praefatio]. This manner of humble servant refers to St. Paul’s writing e.g. Eph 3:8; 1 Cor 15:9, and to some extent it seems to be an allusion to Christ’s verdict that his disciples quarrelled about which one of them would be the greatest (see Lk 9:48). 2 Helmold I, 14: “Testis est magister Adam, qui gesta Hammemburgensis ecclesiae pontificum disertissimo sermone conscripsit …” (“The witness is master Adam, who with great skill and fluency described the deeds of the bishops of the Church in Hamburg …”). -

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II ORREST LEE “WOODY” VOSLER of Lyndonville, Quick Write New York, was a radio operator and gunner during F World War ll. He was the second enlisted member of the Army Air Forces to receive the Medal of Honor. Staff Sergeant Vosler was assigned to a bomb group Time and time again we read about heroic acts based in England. On 20 December 1943, fl ying on his accomplished by military fourth combat mission over Bremen, Germany, Vosler’s servicemen and women B-17 was hit by anti-aircraft fi re, severely damaging it during wartime. After reading the story about and forcing it out of formation. Staff Sergeant Vosler, name Vosler was severely wounded in his legs and thighs three things he did to help his crew survive, which by a mortar shell exploding in the radio compartment. earned him the Medal With the tail end of the aircraft destroyed and the tail of Honor. gunner wounded in critical condition, Vosler stepped up and manned the guns. Without a man on the rear guns, the aircraft would have been defenseless against German fi ghters attacking from that direction. Learn About While providing cover fi re from the tail gun, Vosler was • the development of struck in the chest and face. Metal shrapnel was lodged bombers during the war into both of his eyes, impairing his vision. Able only to • the development of see indistinct shapes and blurs, Vosler never left his post fi ghters during the war and continued to fi re. -

The Reich Wreckers: an Analysis of the 306Th Bomb Group During World War II 5B

AU/ACSC/514-15/1998-04 AIR COMMAND AND STAFF COLLEGE AIR UNIVERSITY THE REICH WRECKERS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE 306TH BOMB GROUP DURING WORLD WAR II by Charles J. Westgate III, Major, USAF A Research Report Submitted to the Faculty In Partial Fulfillment of the Graduation Requirements Advisor: Dr. Richard R. Muller Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 1998 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burder for this collection of information is estibated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burder to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (FROM - TO) 01-04-1998 Thesis xx-xx-1998 to xx-xx-1998 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER The Reich Wreckers: An Analysis of the 306th Bomb Group During World War II 5b. GRANT NUMBER Unclassified 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. -

Record of the Istanbul Process 16/18 for Combating Intolerance And

2019 JAPAN SUMMARY REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS EVENT SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 PLENARY SESSIONS ................................................................................................................................. 7 LAUNCHING THE 2019 G20 INTERFAITH FORUM.......................................................................... 7 FORMAL FORUM INAUGURATION – WORKING FOR PEACE, PEOPLE, AND PLANET: CHALLENGES TO THE G20 ............................................................................................................... 14 WHY WE CAN HOPE: PEACE, PEOPLE, AND PLANET ................................................................. 14 ACTION AGENDAS: TESTING IDEAS WITH EXPERIENCE FROM FIELD REALITIES ........... 15 IDEAS TO ACTION .............................................................................................................................. 26 TOWARDS 2020 .................................................................................................................................... 35 CLOSING PLENARY ............................................................................................................................ 42 PEACE WORKING SESSIONS ................................................................................................................ 53 FROM VILE TO VIOLENCE: FREEDOM OF RELIGION & BELIEF & PEACEBUILDING ......... 53 THE DIPLOMACY OF RELIGIOUS PEACEBUILDING .................................................................. -

The Blitz and Its Legacy

THE BLITZ AND ITS LEGACY 3 – 4 SEPTEMBER 2010 PORTLAND HALL, LITTLE TITCHFIELD STREET, LONDON W1W 7UW ABSTRACTS Conference organised by Dr Mark Clapson, University of Westminster Professor Peter Larkham, Birmingham City University (Re)planning the Metropolis: Process and Product in the Post-War London David Adams and Peter J Larkham Birmingham City University [email protected] [email protected] London, by far the UK’s largest city, was both its worst-damaged city during the Second World War and also was clearly suffering from significant pre-war social, economic and physical problems. As in many places, the wartime damage was seized upon as the opportunity to replan, sometimes radically, at all scales from the City core to the county and region. The hierarchy of plans thus produced, especially those by Abercrombie, is often celebrated as ‘models’, cited as being highly influential in shaping post-war planning thought and practice, and innovative. But much critical attention has also focused on the proposed physical product, especially the seductively-illustrated but flawed beaux-arts street layouts of the Royal Academy plans. Reconstruction-era replanning has been the focus of much attention over the past two decades, and it is appropriate now to re-consider the London experience in the light of our more detailed knowledge of processes and plans elsewhere in the UK. This paper therefore evaluates the London plan hierarchy in terms of process, using new biographical work on some of the authors together with archival research; product, examining exactly what was proposed, and the extent to which the different plans and different levels in the spatial planning hierarchy were integrated; and impact, particularly in terms of how concepts developed (or perhaps more accurately promoted) in the London plans influenced subsequent plans and planning in the UK. -

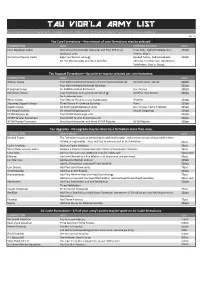

TAU VIOR'la ARMY LIST Tau Vior'la Armies Have a Strategy Rating of 3

TAU VIOR'LA ARMY LIST Tau Vior'la Armies have a Strategy Rating of 3. Crisis Battlesuit Cadres, XV014, KV128 and the Manta are Initiative 1+; all other formations are Initiative 2+. Dev 1.8 Tau Core Formations—Any amount of core formations may be selected. FORMATION UNITS UPGRADES ALLOWED COST Crisis Battlesuit Cadre One Shas'el Commander character and Four XV8 Crisis Crisis Suits, Cadre Fireblade, Gun 250pts Battlesuit units Drones, Shas'o Vior'la Fire Warrior Cadre Eight Fire Warrior units or Bonded Teams, Cadre Fireblade, 225pts Six Fire Warrior units and three Devilfish Ethereal, Fire Warriors, Gun Drones, Pathfinders, Shas'o, Skyray Tau Support Formations—Up to three may be selected per core formation. FORMATION UNITS COST Armour Group Four Hammerhead (Ionhead) or (Fusionhead) Gunships or Hammerheads, Skyray 200pts Four Hammerhead (Railhead) Gunships 225pts Broadside Group Six XV88 Broadside Battlesuits Gun Drones 300pts Pathfinder Group Four Pathfinder units and two Devilfish or Devilfish, Gun Drones 200pts Six Pathfinder units Recon Group Five Tetra or Piranha, in any combination Piranhas 150pts Skysweep Support Group Three Skyray Air Defence Gunships None 250pts Stealth Group Six XV15 Stealth Battlesuit units Gun Drones, Cadre Fireblade 225pts 0-2 Vespid Swarms Six Vespid Stingwing units Vespid Stingwings 150pts KX128 Stormsurge Two KX128 Stormsurge units 250pts KV129 Ta'unar Supremacy One KV129 Ta'unar Supremacy unit 225pts XV104 Riptide Formation One Shas'el character and three XV104 Riptides XV104 Riptide 350pts Tau Upgrades - No upgrade may be taken by a formation more than once. FORMATION UNITS / EFFECT COST Bonded Teams The formation counts as containing an additional Leader and removes an extra blast marker when rallying or regrouping. -

Air Force Next-Generation Bomber: Background and Issues for Congress

Air Force Next-Generation Bomber: Background and Issues for Congress Jeremiah Gertler Specialist in Military Aviation December 22, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34406 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Air Force Next-Generation Bomber: Background and Issues for Congress Summary As part of its proposed FY2010 defense budget, the Administration proposed deferring the start of a program to develop a next-generation bomber (NGB) for the Air Force, pending the completion of the 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) and associated Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), and in light of strategic arms control negotiations with Russia. The Administration’s proposed FY2010 budget requested no funding specifically identified in public budget documents as being for an NGB program. Prior to the submission of the FY2010 budget, the Air Force was conducting research and development work aimed at fielding a next-generation bomber by 2018. Although the proposed FY2010 defense budget proposed deferring the start of an NGB program, the Secretary of Defense and Air Force officials in 2009 have expressed support for the need to eventually start such a program. The Air Force’s FY2010 unfunded requirements list (URL)—a list of programs desired by the Air Force but not funded in the Air Force’s proposed FY2010 budget—includes a classified $140-million item that some press accounts have identified as being for continued work on a next-generation bomber. FY2010 defense authorization bill: The conference report (H.Rept. 111-288 of October 7, 2009) on the FY2010 defense authorization act (H.R. -

H1 Toryjournal

TheWittenberg H1 toryJournal Wittenberg University • Springfield, Ohio Volume XXXII Spring2003 From the Editors: Greetings from the editors of the WittenbergUniversity History Journal. As you may notice, the format for this year's publication has changed from previous issues. We hope that this change is the first step in redefining the journal by making the physical publication even more professional. The within articles are, as always, excellent examples of what students here at Wittenberg are writing, and we hope that you wili enjoy reading them. A very special thanks is due to Tom and Tina Lagos, the Admission Office at Wittenberg and the Wittenberg History Club for their generous donations. Without their financial assistance, this publication would not have been possible. We would also like to thank all those involved in making this journal possible and congratulations to all the writers on creating such superior works. Mark Huber, Mandy Oleson and Dustin Plummer The Wittenberg University History Journal 2002-03 Editorial Staff '04, '03 Co-editors .......................... Mark Huber Mandy Oleson and Dustin Plummet '03 Editorial Staff ................. Erica Fornari '04, Greer Illingworth '05 Nicole Roberts '03 and Rebecca Roush '03 Advisor ......................................................... Dr. Jim Huffman The Hartje Papers The Martha and Robert G. Hartje Award is presented annually to a Senior in the spring semester. The History Department determines the five finalists who write a 600 to 800 word narrative essay dealing with a historical event or figure. The finalists must have at least a 2.7 grade point average and have completed at least six history courses. The winner is awarded $500 at a spring semester History Department colloquium and the winning paper is included in the HistoryJournal. -

The Evolution & Impact of US Aircraft In

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program Fall 10-2019 Take Off to Superiority: The Evolution & Impact of U.S. Aircraft in War Lane Weidner University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Aviation Commons, and the Military History Commons Weidner, Lane, "Take Off to Superiority: The Evolution & Impact of U.S. Aircraft in War" (2019). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 184. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/184 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. TAKE OFF TO SUPERIORITY: THE EVOLUTION & IMPACT OF U.S. AIRCRAFT IN WAR An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial fulfillment of University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska-Lincoln by Lane M. Weidner, Bachelor of Science Major: Mathematics Minor: Aerospace Studies College of Arts & Sciences Oct 24, 2019 Faculty Mentor: USAF Captain Nicole Beebe B.S. Social Psychology M.Ed. Human Resources, E-Learning ii Abstract Military aviation has become a staple in the way wars are fought, and ultimately, won. This research paper takes a look at the ways that aviation has evolved and impacted wars across the U.S. history timeline. With a brief introduction of early flight and the modern concept of an aircraft, this article then delves into World Wars I and II, along with the Cold, Korean, Vietnam, and Gulf Wars. -

Guide to the Doolittle Tokyo Raider Association Papers (1947

Guide to the Doolittle Tokyo Raider Association Papers (1947 - ) 26 linear feet Accession Number: 54-06 Collection Number: H54-06 Collection Dates: 1931 - Bulk Dates: 1942 - 2005 Prepared by Thomas J. Allen CITATION: The Doolittle Tokyo Raiders Association Papers, Box number, Folder number, History of Aviation Collection, Special Collections Department, McDermott Library, The University of Texas at Dallas. Special Collections Department McDermott Library, The University of Texas at Dallas Contents Historical Sketch ................................................................................................................. 3 Sources ................................................................................................................................ 3 Additional Sources .............................................................................................................. 3 Series Description ............................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content Note...................................................................................................... 5 Collection Note ................................................................................................................... 8 Provenance Statement ......................................................................................................... 8 Literary Rights Statement ................................................................................................... 8 2