Individuals and the Significance of Affect: Foreign Policy Variation In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel in 1982: the War in Lebanon

Israel in 1982: The War in Lebanon by RALPH MANDEL LS ISRAEL MOVED INTO its 36th year in 1982—the nation cele- brated 35 years of independence during the brief hiatus between the with- drawal from Sinai and the incursion into Lebanon—the country was deeply divided. Rocked by dissension over issues that in the past were the hallmark of unity, wracked by intensifying ethnic and religious-secular rifts, and through it all bedazzled by a bullish stock market that was at one and the same time fuel for and seeming haven from triple-digit inflation, Israelis found themselves living increasingly in a land of extremes, where the middle ground was often inhospitable when it was not totally inaccessible. Toward the end of the year, Amos Oz, one of Israel's leading novelists, set out on a journey in search of the true Israel and the genuine Israeli point of view. What he heard in his travels, as published in a series of articles in the daily Davar, seemed to confirm what many had sensed: Israel was deeply, perhaps irreconcilably, riven by two political philosophies, two attitudes toward Jewish historical destiny, two visions. "What will become of us all, I do not know," Oz wrote in concluding his article on the develop- ment town of Beit Shemesh in the Judean Hills, where the sons of the "Oriental" immigrants, now grown and prosperous, spewed out their loath- ing for the old Ashkenazi establishment. "If anyone has a solution, let him please step forward and spell it out—and the sooner the better. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS April 13, 1989 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS Yielding to Extraordinary Economic Pres Angola

6628 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS April 13, 1989 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS Yielding to extraordinary economic pres Angola. Already cut off from South African TESTIMONY OF HOWARD sures from the U.S. government, South aid, which had helped stave off well funded PHILLIPS Africa agreed to a formula wherein the anti invasion-scale Soviet-led assaults during communist black majority Transitional 1986 and 1987, UNITA has been deprived by HON. DAN BURTON Government of National Unity, which had the Crocker accords of important logistical been administering Namibia since 1985, supply routes through Namibia, which ad OF INDIANA would give way to a process by which a new joins liberated southeastern Angola. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES government would be installed under United If, in addition, a SWAPO regime were to Thursday, April 13, 1989 Nations auspices. use Namibia's Caprivi Strip as a base for South Africa also agreed to withdraw its anti-UNITA Communist forces, UNITA's Mr. BURTON of Indiana. Mr. Speaker, I estimated 40,000 military personnel from ability to safeguard those now resident in would like to enter a statement by Mr. Howard Namibia, with all but 1,500 gone by June 24, the liberated areas would be in grave ques Phillips of the Conservative Caucus into the to dismantle the 35,000-member, predomi tion. RECORD. In view of recent events in Namibia, nantly black, South West African Territori America has strategic interests in south al Force, and to permit the introduction of ern Africa. The mineral resources concen I think it is very important for all of us who are 6,150 U.N. -

Israeli Media Self-Censorship During the Second Lebanon War

conflict & communication online, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2019 www.cco.regener-online.de ISSN 1618-0747 Sagi Elbaz & Daniel Bar-Tal Voluntary silence: Israeli media self-censorship during the Second Lebanon War Kurzfassung: Dieser Artikel beschreibt die Charakteristika der Selbstzensur im Allgemeinen, und insbesondere in den Massenmedien, im Hinblick auf Erzählungen von politischer Gewalt, einschließlich Motivation und Auswirkungen von Selbstzensur. Es präsentiert zunächst eine breite theoretische Konzeptualisierung der Selbstzensur und konzentriert sich dann auf seine mediale Praxis. Als Fallstudie wurde die Darstellung des Zweiten Libanonkrieges in den israelischen Medien untersucht. Um Selbstzensur als einen der Gründe für die Dominanz hegemonialer Erzählungen in den Medien zu untersuchen, führten die Autoren Inhaltsanalysen und Tiefeninterviews mit ehemaligen und aktuellen Journalisten durch. Die Ergebnisse der Analysen zeigen, dass israelische Journalisten die Selbstzensur weitverbreitet einsetzen, ihre Motivation, sie zu praktizieren, und die Auswirkungen ihrer Anwendung auf die Gesellschaft. Abstract: This article describes the characteristics of self-censorship in general, specifically in mass media, with regard to narratives of political violence, including motivations for and effects of practicing self-censorship. It first presents a broad theoretical conceptualization of self-censorship, and then focuses on its practice in media. The case study examined the representation of The Second Lebanon War in the Israeli national media. The authors carried out content analysis and in-depth interviews with former and current journalists in order to investigate one of the reasons for the dominance of the hegemonic narrative in the media – namely, self-censorship. Indeed, the analysis revealed widespread use of self-censorship by Israeli journalists, their motivations for practicing it, and the effects of its use on the society. -

ISRAEL's TRUTH-TELLING WITHOUT ACCOUNTABILITY Inquest Faults

September 1991 IIISRAEL'''S TTTRUTH---T-TTTELLING WITHOUT AAACCOUNTABILITY Inquest Faults Police in Killings at Jerusalem HolyHoly Site But Judge Orders No Charges Table of Contents I. Introduction........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Confrontation: Sequence of Events............................................................................................................................................................ 6 III. Judge Kama's Findings on Police Conduct.................................................................................................................................................... 8 IV. The Case for Prosecution ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 I. Introduction Middle East Watch commends the extensive investigation published by Israeli Magistrate Ezra Kama on July 18 into the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif killings. However, Middle East Watch is disturbed that, in light of evidence establishing criminal conduct by identifiable police officers, none of the officers involved in the incident has been prosecuted or disciplined. Middle East Watch also believes that the police's criminal investigation of the incident last fall was grossly negligent and in effect sabotaged the -

Western Europe

Western Europe Great Britain National Affairs OIGNS OF SLOW BUT DISCERNIBLE economic recovery in 1993 —such as a drop in interest rate, reduced inflation, and even a small decline in unemploy- ment — did nothing to halt the unremitting decline in the political fortunes of Prime Minister John Major's Conservative government. The Tories lost to the Liberal Democrats in by-elections for two hitherto safe parliamentary seats — Newbury in May and Christchurch in July — and in local elections in May, when the Conserva- tives lost control of all but one county council. The most likely cause of the government's unpopularity was its own disunity. Internal dissension, for example, dogged the progress of the bill to ratify the Maas- tricht Treaty on European Union. In March the government lost a key vote on the bill by 22 votes, and Major had to call for a vote of confidence in July, which did insure final ratification of the treaty. The Labor party limited itself to profiting from the government's unpopularity and to updating its image and organization. Under leader John Smith's impetus, the party's annual conference in September voted to abolish the bloc vote enjoyed by the trade unions, in a bid to enhance the party's appeal to middle-class electors. Despite appeals by the Board of Deputies of British Jews and other groups, the government's Asylum Bill, which would limit the number of political refugees admitted to Britain, was passed by the House of Commons in January. Israel and the Middle East The draft peace accord signed by Israel and the Palestinians in September was welcomed by all political parties and opened the door to a more positive stance by Britain in Middle East politics. -

The Army and Society Forum the IDF and the PRESS DURING HOSTILITIES

The Army and Society Forum THE IDF AND THE PRESS DURING HOSTILITIES ��� ������ ������� ������ ��� ������ ��������� ��������� ��� ��� ��� ��� ����� ������ ����������� � ��������� ���� �� � ���� ���� �� ��� ������ ��������� ��������� ��� ���� ��� ������� ����� 5 Editor in Chief: Uri Dromi Administrative Director, Publications Dept.: Edna Granit English Publications Editor: Sari Sapir Translators: Miriam Weed Sari Sapir Editor: Susan Kennedy Production Coordinator: Nadav Shtechman Graphic Designer: Ron Haran Printed in Jerusalem by The Old City Press © 2003 The Israel Democracy Institute All rights reserved. ISBN 965-7091-67-5 Baruch Nevo heads The Army and Society Forum at The Israel Democracy Institute and is Professor of Psychology at Haifa University. Yael Shur is a research assistant at The Israel Democracy Institute. The views in this publication are entirely those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Israel Democracy Institute. 5 Table of Contents PART ONE The IDF and the Press during Hostilities Baruch Nevo and Yael Shur Preface 6 Introduction 7 The Media as a Strategic Consideration in Preparation for War 13 The IDF and the Media: Reciprocal Relations 21 A Research Agenda 35 PART TWO Opening Plenary Session 37 Discussion Groups Group 1: The Media as a Strategic Consideration in Preparation for War 58 Group 2: The IDF's Approach to the Media 88 Group 3: The Media’s Stance towards the IDF 119 Closing Plenary Session 139 Group Reports 151 6 The IDF and the Press during Hostilities 7 PART ONE The IDF and the Press during Hostilities Baruch Nevo and Yael Shur PREFACE The fifth meeting of the Army and Society Forum, held in the summer of 2002, dealt with issues related to the IDF (Israel Defense Forces) and the media in wartime. -

Camp David's Shadow

Camp David’s Shadow: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinian Question, 1977-1993 Seth Anziska Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Seth Anziska All rights reserved ABSTRACT Camp David’s Shadow: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinian Question, 1977-1993 Seth Anziska This dissertation examines the emergence of the 1978 Camp David Accords and the consequences for Israel, the Palestinians, and the wider Middle East. Utilizing archival sources and oral history interviews from across Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, the United States, and the United Kingdom, Camp David’s Shadow recasts the early history of the peace process. It explains how a comprehensive settlement to the Arab-Israeli conflict with provisions for a resolution of the Palestinian question gave way to the facilitation of bilateral peace between Egypt and Israel. As recently declassified sources reveal, the completion of the Camp David Accords—via intensive American efforts— actually enabled Israeli expansion across the Green Line, undermining the possibility of Palestinian sovereignty in the occupied territories. By examining how both the concept and diplomatic practice of autonomy were utilized to address the Palestinian question, and the implications of the subsequent Israeli and U.S. military intervention in Lebanon, the dissertation explains how and why the Camp David process and its aftermath adversely shaped the prospects of a negotiated settlement between Israelis and Palestinians in the 1990s. In linking the developments of the late 1970s and 1980s with the Madrid Conference and Oslo Accords in the decade that followed, the dissertation charts the role played by American, Middle Eastern, international, and domestic actors in curtailing the possibility of Palestinian self-determination. -

Kurdistan Iraq

Oil magazine no. 27/2014 - Targeted mailshot T 4 N . 0 o 0 u E U w R m O h S b v b e o r e e a a 27 r r r N l r O d V E M B e E R 2014 l magazine e n EDITORIAL i z a g a m Eni quarterly Year 7 - N. 27 November 2014 Authorization from the Court of Rome After the sheikhs: The coming No. 19/2008 dated 01/21/2008 The world over a barrel n Editor in chief Gianni Di Giovanni n Editorial committee collapse of the Gulf monarchies Paul Betts, Fatih Birol, Bassam Fattouh, Guido Gentili, Gary Hart, Harold W. Kroto, he entire Middle East region and East situation extremely well, puts Alessandro Lanza, Lifan Li, e nyone who has anything to cially the United States, the United Kingdom and the n i z a g a Molly Moore, Edward Morse, m also North Africa appear to be forward the theory - difficult to NOVEMBER 2014 Moisés Naím, Daniel Nocera, do with oil must read European Union; the armed forces; the secret police; The Carlo Rossella, Giulio Sapelli world in the midst of a serious crisis. implement but not Utopian - of an Christopher M. Davidson’s and the backing of many citizens, a rich “nomen- over T n a Scientific committee barrel The epicenter, this time, is Syria and international conference, a sort 2013 book After The Sheikhs: clatura” that enjoys the economic privileges that oil Geminello Alvi, Antonio Galdo, Raffaella Leone, Marco Ravaglioli, Iraq, where a civil war is raging and of new Congress of Vienna. -

Israel Report Is a Student Publication of Sudan

To provide greater exposure to primary Israeli news sources and opinions in order to become better informed on the issues, and to gain a better understanding of the wide range of perspectives that exist in Israeli society and politics. Issue 991 • January 29, 2016 • 18 Shevat 5776 ISRAEL SLAMS UN CHIEF'S HYPOCRISY (Israel Hayom 1/27/16) The Ministry of Health in Gaza spokesman denied the reports, claiming no Israeli officials in Jerusalem were infuriated on Tuesday by U.N. Secretary- bodies were brought to the hospital from the tunnel collapse. On Saturday, General Ban Ki-moon's criticism of settlement activities in Judea and the Ministry reported that a Hamas militant was killed in tunnel collapse in Samaria. Khan Yunis. Addressing the U.N. Security Council on Tuesday, Ban said, "As oppressed Hamas has been steadily rebuilding its military terrorist infrastructure since peoples have demonstrated throughout the ages, it is human nature to react since Operation Protective Edge last summer, including the restocking of its to occupation." The U.N. chief called Israeli settlement activities "an affront to rocket arsenal and the digging of attack tunnels, including some that reach the Palestinian people and to the international community. ... They rightly inside Israeli territory. raise questions about Israel's commitment to a two-state solution." It is estimated that since the end of Protective Edge, Hamas has dug dozens At the same Security Council meeting, U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. of tunnels of varying lengths. Samantha Power said the U.S. "strongly opposes settlement activity," but she 32 tunnels were dug by the summer of 2014, and according to a senior IDF added that "settlement activity can never in itself be an excuse for violence." source, they were all destroyed completely during the war to the extent that it Later on Tuesday, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu issued a stinging would be impossible to reconstruct them. -

July 2015 - Reflections from the CEO by Linda Kislowicz

Chair Julia Berger Reitman President & CEO Linda Kislowicz July 2015 - Reflections from the CEO By Linda Kislowicz I have just returned from a very intense month in Israel. A week of Keren Hayesod and Jewish Agency meetings was followed by a complete tour of the Canadian partnership regions - Eilat/Eilot, Bat Yam/Kiryat Moshe, Sderot, Beer Sheva/B’nei Shimon and the five northern communities in Etzba Hagalil - where I held strategic meetings with Israeli colleagues and partners. My tour ended with some personal family time. What follows are my thoughts and impressions following this inspiring journey. Highlights of the Keren Hayesod-UIA and Jewish Agency Meetings The annual Keren Hayesod – UIA conference took place in the beautiful winery region of the Judean Hills. The itinerary included a visit to a naval base in Ashdod, a briefing by Ambassador Ron Prosor, Israel's 16th Permanent Representative to the United Nations and several award presentations including the Israel Goldstein Prize for Distinguished Leadership to Ambassador Avi Pazner, the Yakir Award presentations and the Avi-Hai Award for Exemplary Young Leadership to Jason Rubinoff from Toronto and Fabiënne Meijers from Amsterdam. Kesher – the Julia Koschitzky Seminar for Keren Hayesod Young Leadership, which included 4 Canadian participants, coincided with the annual KH conference. Key agenda items focused on engaging younger leaders, strengthening and rejuvenating campaigns around the world and exploring new funding models relevant to the younger generation of donors. The Jewish -

Israel's Wars, 1947-93

Israel’s Wars, 1947–93 Warfare and History General Editor Jeremy Black Professor of History, University of Exeter European warfare, 1660–1815 Jeremy Black The Great War, 1914–18 Spencer C. Tucker Wars of imperial conquest in Africa, 1830–1914 Bruce Vandervort German armies: war and German politics, 1648–1806 Peter H. Wilson Ottoman warfare, 1500–1700 Rhoads Murphey Seapower and naval warfare, 1650–1830 Richard Harding Air power in the age of total war, 1900–60 John Buckley Frontiersmen: warfare in Africa since 1950 Anthony Clayton Western warfare in the age of the Crusades, 1000–1300 John France The Korean War Stanley Sandler European and Native-American warfare, 1675–1815 Armstrong Starkey Vietnam Spencer C. Tucker The War for Independence and the transformation of American society Harry M. Ward Warfare, state and society in the Byzantine world, 565–1204 John Haldon Soviet military system Roger Reese Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500–1800 John K. Thornton The Soviet military experience Roger Reese Warfare at sea, 1500–1650 Jan Glete Warfare and society in Europe, 1792–1914 Geoffrey Wawro Israel’s Wars, 1947–93 Ahron Bregman Israel’s Wars, 1947–93 Ahron Bregman London and NewYork First published 2000 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, NewYork, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2001. © 2000 Ahron Bregman All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Conference Program

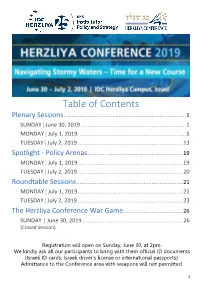

Table of Contents Plenary Sessions .............................................................................. 1 SUNDAY | June 30, 2019 ................................................................... 1 MONDAY | July 1, 2019 ..................................................................... 5 TUESDAY | July 2, 2019 ................................................................... 13 Spotlight - Policy Arenas ............................................................. 19 MONDAY | July 1, 2019 ................................................................... 19 TUESDAY | July 2, 2019 ................................................................... 20 Roundtable Sessions .................................................................... 21 MONDAY | July 1, 2019 ................................................................... 21 TUESDAY | July 2, 2019 ................................................................... 23 The Herzliya Conference War Game ...................................... 26 SUNDAY | June 30, 2019 ................................................................ 26 (Closed Session) Registration will open on Sunday, June 30, at 2pm. We kindly ask all our participants to bring with them official ID documents (Israeli ID cards, Israeli driver’s license or international passports). Admittance to the Conference area with weapons will not permitted. 1 Plenary Sessions SUNDAY | June 30, 2019 14:00 Welcome & Registration 15:00 Opening Ceremony Prof. Uriel Reichman, President & Founder, IDC Herzliya Prof.