In Vladimir Sorokin's Blue Lard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01 Schmid Russ Medien.Indd

Facetten der Medienkultur Band 6 Herausgegeben von Manfred Bruhn Vincent Kaufmann Werner Wunderlich Ulrich Schmid (Hrsg.) Russische Medientheorie Aus dem Russischen von Franziska Stöcklin Haupt Verlag Bern Stuttgart Wien Ulrich Schmid (geb. 1965) studierte Slavistik, Germanistik und Politologie an den Universitäten Zürich, Heidelberg und Leningrad. Seit 1993 arbeitet er als freier Mitarbeiter im Feuilleton der Neuen Zürcher Zeitung NZZ. 1995–1996 forschte er als Visiting Fellow an der Harvard University. Von 1992–2000 war er Assistent, von 2000–2003 Assistenzprofessor am Slavischen Seminar der Universität Basel. 2003–2004 Assistenzprofessor am Institut für Slavistik der Universität Bern, seit 2005 Ordinarius für slavische Literaturwissenschaft an der Ruhr-Universität Bochum. Publiziert mit der freundlichen Unterstützung durch die Schweizerische Akademie der Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften (SAGW) Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek: Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Na- tionalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. ISBN 3-258-06762-7 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Copyright © 2005 Haupt Verlag Berne Jede Art der Vervielfältigung ohne Genehmigung des Verlages ist unzulässig. Umschlag: Atelier Mühlberg, Basel Satz: Verlag Die Werkstatt, Göttingen Printed in xxx http://www.haupt.ch Inhalt Einleitung Ulrich Schmid Russische Medientheorien xx Grundlagen einer Medientheorie in Russland Nikolai Tschernyschewski Die ästhetischen Beziehungen der Kunst zur Wirklichkeit (1855) xx Lew Tolstoi Was ist Kunst? (1899) xx Pawel Florenski Die umgekehrte Perspektive (1920) xx Josif Stalin Der Marxismus und die Fragen der Sprachwissenschaft (1950) xx Michail Bachtin Das Problem des Textes in der Linguistik, Philologie und anderen Geisteswissenschaften. Versuch einer philosophischen Analyse (1961) xx Juri Lotman Theatersprache und Malerei. -

The Vagina Monologues by Eve Ensler

The Vagina Monologues by Eve Ensler Official guidelines and script for the V-Day 2004 College Campaign Available by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc. To order copies of the beautiful, bound acting edition of the script of “The Vagina Monologues” (the original – slightly different from the V-Day version of the script) for memento purposes, to sell at your event, or for use in theatre or other classes or workshops, please contact: Customer Service DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC. 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016 Telephone: 212-683-8960, Fax: 212-213-1539 You may also order the acting edition online at www.dramatists.com. Ask for: Book title: The Vagina Monologues ISBN: 0-8222-1772-4 Price: $5.95 Be sure to mention that you represent the V-Day College Campaign. DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC. Representing the American theatre by publishing and licensing the works of new and established playwrights. For more than 65 years Dramatists Play Service, Inc. has provided the finest plays by both established writers and new playwrights of exceptional promise. Formed in 1936 by a number of prominent playwrights and theatre agents, Dramatists Play Service, Inc. was created to foster opportunity and provide support for playwrights by publishing acting editions of their plays and handling the nonprofessional and professional leasing rights to these works. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. has grown steadily to become one of the premier play-licensing agencies in the English speaking theatre. Offering an extensive list of titles, including a preponderance of the most significant American plays of the past half-century, Dramatists Play Service, Inc. -

Swearing a Cross-Cultural Study in Asian and European Languages

Swearing A cross-cultural study in Asian and European Languages Thesis Submitted to Radboud University Nijmegen For the degree of Master of Arts (M.A) Name: Syahrul Rahman / s4703944 Email: [email protected] Supervisor 1: Dr. Ad Foolen Supervisor 2: Professor Helen de Hoop Master Linguistics Radboud University Nijmegen 2016/2017 0 Acknowledgment In the name of Allah, the beneficent and merciful. All praises be to Allah for His mercy and blessing. He has given me health and strength to complete this master thesis as particular instance of this research. Then, may His peace and blessing be upon to His final prophet and messenger, Muhammad SAW, His family and His best friends. In writing and finishing this thesis, there are many people who have provided their suggestion, motivation, advice and remark that all have helped me to finish this paper. Therefore, I would like to express my big appreciation to all of them. For the first, the greatest thanks to my beloved parents Abd. Rahman and Nuriati and my family who have patiently given their love, moral values, motivation, and even pray for me, in every single prayer just to wish me to be happy, safe and successful, I cannot thank you enough for that. Secondly, I would like to dedicate my special gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Ad Foolen, thanking him for his guidance, assistance, support, friendly talks, and brilliant ideas that all aided in finishing my master thesis. I also wish to dedicate my big thanks to Helen de Hoop, for her kind willingness to be the second reviewer of my thesis. -

The Vagina Monologues by Eve Ensler

The Vagina Monologues by Eve Ensler The official script for the 2008 V-Day Campaigns Available by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc. To order copies of the acting edition of the script of “The Vagina Monologues” (the original – different from the V-Day version of the script) for memento purposes, to sell at your event, or for use in theatre or other classes or workshops, please contact: Customer Service DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC. 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016 Telephone: 212-683-8960, Fax: 212-213-1539 You may also order the acting edition online at www.dramatists.com. Ask for: Book title: The Vagina Monologues ISBN: 0-8222-1772-4 Price: $5.95 Be sure to mention that you represent the V-Day College or Worldwide Campaign. DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC. Representing the American theatre by publishing and licensing the works of new and established playwrights. For more than 65 years Dramatists Play Service, Inc. has provided the finest plays by both established writers and new playwrights of exceptional promise. Formed in 1936 by a number of prominent playwrights and theatre agents, Dramatists Play Service, Inc. was created to foster opportunity and provide support for playwrights by publishing acting editions of their plays and handling the nonprofessional and professional leasing rights to these works. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. has grown steadily to become one of the premier play-licensing agencies in the English speaking theatre. Offering an extensive list of titles, including a preponderance of the most significant American plays of the past half-century, Dramatists Play Service, Inc. -

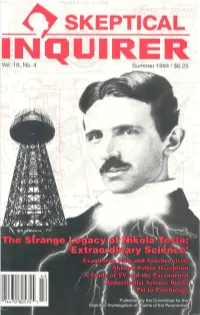

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

Word Bank of Lost Dialects

A to Z Words and phrases collected by the Word Bank This is a full list of all the words and phrases that were donated by visitors to the original Lost Dialects exhibition at The Word from October 2016 – June 2018. Some have been lightly edited for punctuation, consistency and readability. Alternative spellings and missing definitions that have been subsequently added are indicated in italics. Words Word Definition(s) Allies Marbles Alreet Are you ok, how are you?, hello, ok, yes Armu Unappreciated Ashy Poor Aye Yes Babby Baby Back-ower Reverse Bagsy To choose or pick Baigey Turnip Bairn A child, baby Bait A packed meal, food (sandwiches etc.), lunch Baldi Bald person Baltic Incredibly cold Bampot or barmpot A crazy or silly person Banger Bone shaker bicycle Banta Chat between people Bantling Infant Bari Good, something that is good or nice Barnet Hair Barra Shopping trolley Bash Hit Beaver Beard Beek Nose Belta Excellent, really good, great, fantastic, brilliant Benker A metal marble Billet Home Blackfasten Not bothered, not enthusiastic Blamma A hard kick Blate Shy Blather Talk too much Bleezer Metal plate used to draw air into fireplace Blether Talk Blindin’ Something that’s great INDEX OF WORDS A to Bli Word Definition(s) Blocka A game Boake Puke, gag Bobbins Rubbish Bog A toilet Bogey Homemade go-kart, usually old pram wheels Bogie Snot Boilie Bread and milk Bonny Pretty, pretty nice, beautiful, good looking Boodie or boody Pottery, broken pieces of china buried in the ground Bostin Good Brassant or brass Money Brassic Skint, no money -

The Use of Swear Words in English and Russian Phraseological Units

The Use of Swear Words in English and Russian Phraseological Units Malenica, Ella Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zadar / Sveučilište u Zadru Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:162:845537 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: University of Zadar Institutional Repository of evaluation works Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Diplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti; smjer: nastavnički (dvopredmetni) Ella Malenica The Use of Swear Words in English and Russian Phraseological Units Diplomski rad Zadar, 2020. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Diplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti; smjer: nastavnički (dvopredmetni) The Use of Swear Words in English and Russian Phraseological Units Diplomski rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Ella Malenica dr.sc. Ivo Fabijanić Zadar, 2020. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Ella Malenica, ovime izjavljujem da je moj diplomski rad pod naslovom The Use of Swear Words in English and Russian Phraseological Units rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga rada. Zadar, 28. svibnja 2020. Table of Contents 1. -

Page 1 DOCUMENT RESUME ED 335 965 FL 019 564 AUTHOR

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 335 965 FL 019 564 AUTHOR Riego de Rios, Maria Isabelita TITLE A Composite Dictionary of Philippine Creole Spanish (PCS). INSTITUTION Linguistic Society of the Philippines, Manila.; Summer Inst. of Linguistics, Manila (Philippines). REPORT NO ISBN-971-1059-09-6; ISSN-0116-0516 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 218p.; Dissertation, Ateneo de Manila University. The editor of "Studies in Philippine Linguistics" is Fe T. Otanes. The author is a Sister in the R.V.M. order. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Vocabularies/Classifications/Dictionaries (134)-- Dissertations/Theses - Doctoral Dissertations (041) JOURNAL CIT Studies in Philippine Linguistics; v7 n2 1989 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Creoles; Dialect Studies; Dictionaries; English; Foreign Countries; *Language Classification; Language Research; *Language Variation; Linguistic Theory; *Spanish IDENTIFIERS *Cotabato Chabacano; *Philippines ABSTRACT This dictionary is a composite of four Philippine Creole Spanish dialects: Cotabato Chabacano and variants spoken in Ternate, Cavite City, and Zamboanga City. The volume contains 6,542 main lexical entries with corresponding entries with contrasting data from the three other variants. A concludins section summarizes findings of the dialect study that led to the dictionary's writing. Appended materials include a 99-item bibliography and materials related to the structural analysis of the dialects. An index also contains three alphabetical word lists of the variants. The research underlying the dictionary's construction is -

Berrington, Robin

Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series ROBIN BERRINGTON Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: April 13, 2000 Copyright 2011 ADS TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in Ohio Wesleyan University, Harvard University Study in Japan Appointed Foreign Service Officer, 1969 Kamphaeng Phet, Thailand: Peace Corps, English instructor 1963-196. Training, University of Indiana Relations 0it US Em1assy USIS Operations Harvard University: %apanese language study 196.-1962 Sakon Nak on, T ailand: USIS 1968-1969 Broadcast, Counterinsurgency ne0s Communists American official presence Relations 0it T ais Relations 0it Em1assy Security Operations T ai military US Am1assadors 5ala, T ailand: Branc Pu1lic Affairs Officer 1969 6uslim insurgents 6alayan Communist Party 6o1ile Information Teams 7ietnam War 1 Tokyo, %apan: Assistant Cultural Affairs Officer 1969 5oko ama, %apan: %apanese language study 1969 Fukuoka, %apan: Branc Pu1lic Affairs Officer 1969-192, (yus u9 Fukuoka environment Relations 0it US military Political tensions Anti-US demonstrations :engakuren USIA programs US military Pu1lic Information Officers Political orientation Local media US Navy 7ietnam %apanese business leaders University faculties %apanese relations 0it neig 1ors %apanese armed forces %apanese attitude to0ard outsiders %apanese cultural differences (oreans Social classes %apanese central government %apanese interest in t e arts American Cultural Center Li1rary Alan Carter Tokyo, -

Malebicta INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of VERBAL AGGRESSION

MAlebicTA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF VERBAL AGGRESSION III . Number 2 Winter 1979 REINHOLD AMAN ," EDITOR -a· .,.'.""",t!. 1'''' ...... ".......... __... CD MALEDICTA PRESS WAUKESHA 196· - MALEDICTA III Animal metaphors: Shit linked with animal names means "I don't believe a word of it," as in pig, buzzard, hen, owl, whale, turtle, rat, cat, and bat shit, as well as the ever-popular horseshit. But bullshit remains the most favored, probably because of the prodigious quantity of functional droppings associated with the beast. On payday the eagle shits. Ill. Insults Shit on YDU!, eat shit!, go shit in your hat!, full ofshit, tough shit, shit-head (recall Lieutenant Scheisskopf in Catch-22), ELEMENTARY RUSSIAN OBSCENITY You shit, little shit, stupid shit, dumb shit, simple shit, shit heel; he don't know shit from Shinola, shit or get offthe pot, ·Boris Sukitch Razvratnikov chickenshit, that shit don't fetch, to be shit on, not worth diddly (or doodly) shit, don't know whether to shit orgo blind, he thinks his shit don't stink, he thinks he's King Shit, shit This article wiII concern itself with the pedagogical problems eating grin. encountered in attempting to introduce the basic concepts of IV: Fear Russian obscenity (mat) to English-speaking first-year students Scared shitless, scare the shit out of, shit green (or blue), shit at the college level. The essential problem is the fact that Rus .v,''' bricks, shit bullets, shit little blue cookies, shit out of luck, sian obscenity is primarily derivational while English (i.e., in 'r" almost shit in his pants (or britches), on someone's shit-list, this context, American) obscenity is analytic. -

A Collection of Personal Essays

WHEN WE FIND HOMES: A COLLECTION OF PERSONAL ESSAYS A thesis submitted to the Kent State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors by Joyce Ng Yoon Yi May, 2014 Thesis written by Joyce Ng Yoon Yi Approved by , Advisor , Chair, Department of English Accepted by , Dean, Honors College ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................................iv CHAPTER I. CRITICAL INTRODUCTION................................................................................1 II. PERSONAL INTRODUCTION..............................................................................5 PAST III. SHAPESHIFTING.................................................................................................11 IV. TAKING THE STAGE..........................................................................................23 V. HOLIER THAN THOU.........................................................................................33 PRESENT VI. MY NAMES..........................................................................................................40 VII. IN BETWEEN PLACES.......................................................................................46 VIII. HOME AGAIN......................................................................................................65 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................73 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Dr. Elizabeth Howard—thank -

The Army Lawyer (ISSN 0364-1287)

Headquarters Department of the Army Department of the Army Pamphlet 27-50-251 October 1993 Table of Contents f- Articles A“Society Ap&?”TheMilitary’s Response totheTheatof AIDS.................................................................................................................................... 3 Elizabeth Beard McLuughlin United Stares v. Berri: The Automatism Defense Rears Its Ugly Little Head ................................. .................................................................................... 17 Major Michael J. Davidson and Captain Steve Walters USALSA Report ............................................. ....................................................................................................................... 26 ..................................... United States Army Legal Services Agency The Advocate for Military Defense Counsel DAD Notes ............................ .............................................................................................. 26 ......................................... The ACMR clarifies Berrelson Inquiry Requirementsin Mixed-PleaCourts-Martial;Do Military Judges Pass ConstitutionalMuster? TJAGsA Practice Notes ............... .................................................................................................................................................. 31 Faculfy, The Judge Advocate General’s School Criminal Law Notes ............................................................................. ..........................................................................................................................