Statues Are Not History. Here Are Six in Australia That Need Rethinking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Following the Camel and Compass Trail One Hundred Years On

Following the Camel and Compass Trail One Hundred Years on Ken LEIGHTON1 and James CANNING2, Australia Key words: Historical surveying, early Indigenous contact, Canning Stock Route SUMMARY In this paper, the authors Ken Leighton and James Canning tell the story of one of the most significant explorations in the history of Western Australia, carried out in arduous conditions by a dedicated Surveyor and his team in 1906. The experiences of the original expedition into remote Aboriginal homelands and the subsequent development of the iconic “Canning Stock Route” become the subject of review as the authors investigate the region and the survey after the passage of 100 years. Employing a century of improvements in surveying technology, the authors combine desktop computations with a series of field survey expeditions to compare survey results from the past and present era, often with surprising results. History Workshop - Day 2 - The World’s Greatest Surveyors - Session 4 1/21 Ken Leighton and James Canning Following the camel and compass trail one hundred years on (4130) FIG Congress 2010 Facing the Challenges – Building the Capacity Sydney Australia, 9 – 10 April 2010 Following the Camel and Compass Trail One Hundred Years on Ken LEIGHTON1 and James CANNING2, Australia ABSTRACT In the mere space of 100 years, the world of surveying has undergone both incremental and quantum leaps. This fact is exceptionally highlighted by the recent work of surveyors Ken Leighton and James Canning along Australia’s most isolated linear landscape, the Canning Stock Route. Stretching 1700 kilometres through several remote Western Australian deserts, this iconic path was originally surveyed by an exploration party in 1906, led by a celebrated Government Surveyor; Alfred Wernam Canning. -

Martu Paint Country

MARTU PAINT COUNTRY THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF COLOUR AND AESTHETICS IN WESTERN DESERT ROCK ART AND CONTEMPORARY ACRYLIC ART Samantha Higgs June 2016 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University Copyright by Samantha Higgs 2016 All Rights Reserved Martu Paint Country This PhD research was funded as part of an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Project, the Canning Stock Route (Rock art and Jukurrpa) Project, which involved the ARC, the Australian National University (ANU), the Western Australian (WA) Department of Indigenous Affairs (DIA), the Department of Environment and Climate Change WA (DEC), The Federal Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA, now the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Population and Communities) the Kimberley Land Council (KLC), Landgate WA, the Central Desert Native Title Service (CDNTS) and Jo McDonald Cultural Heritage Management Pty Ltd (JMcD CHM). Principal researchers on the project were Dr Jo McDonald and Dr Peter Veth. The rock art used in this study was recorded by a team of people as part of the Canning Stock Route project field trips in 2008, 2009 and 2010. The rock art recording team was led by Jo McDonald and her categories for recording were used. I certify that this thesis is my own original work. Samantha Higgs Image on title page from a painting by Mulyatingki Marney, Martumili Artists. Martu Paint Country Acknowledgements Thank you to the artists and staff at Martumili Artists for their amazing generosity and patience. -

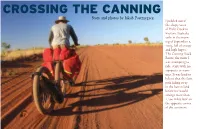

Canning Stock Route, the Route I Was Attempting to Ride, Starts with No Signposts Or Warn- Ings

crossing the canning Story and photos by Jakub Postrzygacz I pedaled out of the sleepy town of Halls Creek in western Australia early in the morn- ing of September 1, 2005, full of energy and high hopes. The Canning Stock Route, the route I was attempting to ride, starts with no signposts or warn- ings. It was hard to believe that the faint path fading away in the barren land before me would emerge more than 1,200 miles later on the opposite corner of the continent. Seven hours later I was cringing in the Canning in a convoy of specially prepared faint shade of my bike, trembling from vehicles. Even today, anyone wishing to overheating and dehydration. Good judg- complete the trek must organize a substan- ment of your own capabilities is the result tial fuel drop at the route’s halfway point. of experience, but gaining that experience Many attempts to bicycle the track with is often the result of bad judgment. I was motorized backup had failed, and nobody learning fast — with many painful lessons had ever tried to ride it unsupported. I still to come. wanted to be the first. In March 2003, I went to a presentation It took me nearly two years to get ready given by National Geographic journalists for the challenge. The most complex task who had completed an epic automobile was creating a bike that, fully loaded with expedition across the Canning. My eyes supplies, could cover great distances across were riveted to images of a land so differ- a land considered impossible to ride. -

PNS Journal Vol 50 No 4 November 2018

Volume 50 Number 4 November 2018 Perth Numismatic Journal Official publication of the Perth Numismatic Society Inc VICE-PATRON Prof. John Melville-Jones EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE: 2018-2019 PRESIDENT Prof. Walter Bloom FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT Ben Selentin SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT Dick Pot TREASURER Alan Peel SECRETARY Prof. Walter Bloom MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Sandra Vowles MINUTES SECRETARY Ray Peel FELLOWSHIP OFFICER Jim Selby EVENTS COORDINATOR Mike McAndrew ORDINARY MEMBERS Jim Hiddens Jonathan de Hadleigh Miles Goldingham Tom Kemeny JOURNAL EDITOR John McDonald JOURNAL SUB-EDITOR Mike Beech-Jones OFFICERS AUDITOR Vignesh Raj CATERING Lucie Pot PUBLIC RELATIONS OFFICER Tom Kemeny WEBMASTER Prof. Walter Bloom WAnumismatica website Mark Nemtsas, designer & sponsor The Purple Penny www.wanumismatica.org.au Perth Numismatic Journal Vol. 50 No. 4 November 2018 CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE PERTH NUMISMATIC JOURNAL Contributions on any aspect of numismatics are welcomed but will be subject to editing. All rights are held by the author(s), and views expressed in the contributions are not necessarily those of the Society or the Editor. Please address all contributions to the journal, comments and general correspondence to: PERTH NUMISMATIC SOCIETY Inc PO BOX 259, FREMANTLE WA 6959 www.pns.org.au Registered Australia Post, Publ. PP 634775/0045, Cat B WAnumismatica website: www.wanumismatica.org.au Designer & sponsor: Mark Nemtsas, The Purple Penny Perth Numismatic Journal Vol. 50 No. 4 November 2018 EARLY HISTORY OF THE BANK OF NEW SOUTH WALES, INCLUDING THE OPENING OF BRANCHES IN PERTH AND FREMANTLE John Wheatley Major-General Lachlan Macquarie, Governor of New South Wales (‘Macquarie’) first conceived the idea of the Bank of New South Wales (‘the Bank’) and developed and implemented it as ‘His Favourite Measure’ 1. -

Information Technologies and Indigenous Communities 13–15 July 2010 Canberra Workshops 16 July Am

ITIC Information Technologies and Indigenous Communities 13–15 July 2010 Canberra Workshops 16 July am Co-hosted with the ANU and the National Film and Sound Archive and in conjunction with the National Recording Project’s 9th Symposium on Indigenous Music and Dance. CONTENTS Registration 1 Venues 1 Symposium (13-15th July) Workshops (16th July am) Internet Access 1 Transport 1 Preliminary Program 2 Abstracts 9 Participants Biographical Notes 31 VENUE MAP = symposium venues School of Music National Film and Sound Archive Academy of Science Roland Wilson House ITIC Symposium • 1 REGISTraTION Come along and learn a range of skills: from researching your family history online, to learning about the cybertracker th Registration opens at 8.00am on Tuesday the 13 of July in the technology used for mapping, from delivering education Shine Dome (Academy of Science) foyer. modules online, to using social media (Facebook, Twitter and If you have any conference enquiries, please come to the others), from how to undertake audio visual documentation to registration desk. Conference telephone number: 02 6201 how to preserve these materials. 9462. National Film and Sound Archive McCoy Circuit, Acton This venue will host Workshops W4: Audiovisual documentation and W5: Preservation. Please meet at the NFSA reception VENUES area at 9am. Please note that for those interested in attending SYMPOSIUM workshop W4, there will be a briefing at the NFSA on Monday Tuesday 13 – Thursday 15th July the 12th at 1pm, meeting in the reception area at NFSA. The symposium will be held at three venues, all within very ANU School of Music, William Herbert Place (off Childers easy walking distance of one another. -

Siddh Bhatnagar +44 1276 683 764 [email protected]

Siddh Bhatnagar +44 1276 683 764 [email protected] 70x30’ in HD and 4K Travelling the world in a variety of 4x4 vehicles, Andrew St Pierre White brings to television some breath-taking images of a beautiful world, and adventure that is out of this world. He often takes the routes that have not been taken before. They are extremely treacherous and, at the same time, stunningly beautiful. From mega animals in Africa to the hidden caves elsewhere, discover a world that has not been seen before. 2 Episodes Episode 101. Andrew and African guide Dave, explore Zimbabwe to find out if it’s a safe country to explore once again. Great Zimbabwe, Bulawayo, the local currency now being the US dollar, Motopos and Rhode’s grave, buying local art, Hwange National Park and Sinamatella to relive a boyhood dream. Episode 102. Baby elephant and game viewing in Hwange National Park, running short of fuel, buying a 50-Billion dollar bank note, Victoria Falls, Tsetse fly control, wind camping etiquette, Lake Kariba fishing and unforgettable sunsets. Game encounters at Mana Pools on the Zam,bezi River. Episode 103. Namibia is one of the world’s most photogenic countries, and Andrew goes touring. Tree cactus forest, game viewing in the Etosha National park, save the Rhino, vast emptiness and huge elephant of Etosha, luxury lodge on the edge of the salt flats, northern swamplands are a complete contrast, swimming in the Okavango River, making a meal on the banks of the Zambezi, and a night on a houseboat on the Chobe River, watching hippo and lion. -

Rabbits to Australia

Rabbits in Australia Who’s the Bunny? BY MARK KELLETT When rabbits were brought to Australia in the earliest days of settlement, they were regarded as a luxury food and there was no way of foreseeing the damage they would inflict on the Australian landscape. In fact, at first, rabbits were surprisingly difficult to breed – until an enterprising squatter arranged to import a particularly hardy wild strain. N 1859 the wealthy squatter The European rabbit (Oryctolagus rabbits selectively under Thomas Austin had a problem. cuniculus) is native to the Iberian domestication, and eventually several Like many of his peers, he had Peninsula and North Africa. A domestic breeds appeared, among risen from modest beginnings to number of these Spanish wild rabbits them the British silver-grey which was I were brought to the Royal Park in valued for its pelt. the ‘squattocracy’ by farming sheep and he saw himself now as part of Guildford in Britain around the turn Austin was not the first to bring of the 13th Century to provide luxury Australia’s landed gentry. He was rabbits to Australia. For as long as food for the royal family. But those planning the stately mansion of Europeans had settled in Australia, rabbits showed a peculiarity that Barwon Park, where he and his family they had brought rabbits with them. centuries later would also be seen in Descriptions of early importations of could live as they believed upper-class Australia. Although their reproductive domesticated rabbits suggest that they English ladies and gentlemen would. capacity is legendary, they are were usually British silver-greys. -

Yiwarra Kuju the Canning Stock Route

CREATING THE EXHIBITION Admission Admission to Yiwarra Kuju: The Canning Stock Route exhibition For four years, emerging and established Aboriginal artists from 15 and general admission to the National Museum is free. language groups, traditional custodians, and a cross-cultural team of curators and multimedia crew have worked together to produce The National Museum Shop the Canning Stock Route collection and Yiwarra Kuju exhibition. The Museum Shop has an exciting range of gifts and mementos A series of return-to-Country professional development workshops representative of all nine art centres featured in the Yiwarra Kuju were held, including a six-week trek along the stock route. exhibition. Pop in and browse our stunning baskets, jewellery, prints and stationery, and don’t forget to pick up a copy of the exhibition catalogue, This groundbreaking exhibition reveals the richness of desert life which features beautiful images of the complete Canning Stock Route today. It is a story of contact, confl ict and survival, of exodus and collection. return, seen through Aboriginal eyes, and interpreted through their voices, art and new media. Visiting from interstate or overseas? Canberra is just a short fl ight from Sydney and Melbourne. Or you can travel by train, coach or road. It’s an easy three-hour drive from Sydney. For details on Canberra accommodation or information about other When they see the exhibition they’ll fi nd out things to see and do while you are in town, call the Canberra and Region what the stock route is really. This project Visitors Centre on 1300 554 114 or visit www.visitcanberra.com.au. -

Along the Canning Stock Route

ALONG THE CANNING STOCK ROUTE An account of the first motor vehicle journey along the full length of the Canning Stock Route by R. J. Wenholz To Chud and Noel, Henry and Frank and belief in the Australian Legend. Were those days as good as I remember Or am I looking through the rainbows of my mind – again. Do I see the coloured chapters of my life lying there Or just the iridescent shadows of some black and white affair. Kevin Johnson Iridescent Shadows CONTENTS Preface 2016 Preface 1983 PART I Getting There Chapter 1 I Meet the Canning 2 More Pre-amble and Some Preparation 3 South-East to Centre 4 Centre to North-West 5 Yarrie - Enforced Stopover 6 Yarrie to Balfour Downs 7 Balfour Downs to Wiluna PART II The Trip 8 Wiluna to Glen-Ayle 9 Glen-Ayle 10 Glen-Ayle to Durba 11 Durba to Disappoinment 12 Disappoinment to Karara 13 Karara to Separation 14 Separation to Gunowaggi 15 Gunowaggi to Guli 16 Guli to Godfrey Tank 17 Godfrey Tank to Halls Creek and Beyond PART III Epilogue 18 Since Then Bibliography and Acknowledgements Preface (2016) I finished writing this manuscript in 1983. I sent copies to the three men who had helped Chud and myself most in our Canning trip: Frank Welsh, Henry Ward and, of course, Noel Kealley. In a naïve, half-hearted way I contacted a few publishers – none were interested. Back in 1983 it was in hard copy format only. Last year, Phil Bianchi of Hesperian Press, converted the hard copy to digital format for me. -

Cultural Heritage Permits Preparing for Your

Vol 4 Canning Stock Route Preparing for your journey Pg Useful tips 01 Permits Pg All you need to know 11 Cultural Heritage Pg Rock art and archaeology 19 Natural Heritage Pg Understanding the natural beauty 33 Looking after the Canning Pg Stock Route 37 How you can help Kuju Wa n g ka One Indigenous Voice for the Canning Stock Route Kuju Kuju Wa n g ka Wa n g ka One Indigenous Voice for One Indigenous Voice for the Canning Stock Route CANNING STOCK ROUTE CANNING STOCK ROUTE the Canning Stock Route The traditional owners are descendants of people who met with Canning’s teams and often include people who were still living traditionally during the droving days of the Stock Route. They have very detailed knowledge of the country along the length of Foreword the Canning Stock Route. Representatives of these native title areas come together in Kuju Wangka, which is focused on preserving the environmental, cultural and heritage values of the country along the Stock Route. Kuju Wangka is supported by the Kimberley Land Council, Mungarlu Ngurrarankatja Rirraunkaja Aboriginal Corporation, Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa and Central Desert Native Title Services. These agencies work with the traditional owners to help them to preserve and protect their culture, heritage and sites. By purchasing Canning Stock Route Permits, you are supporting the traditional owners along the Canning Stock Route to look after their country and to teach their children about their culture. By observing the requirements of the permits, you will help to preserve the high environmental and heritage values of the Canning Stock Route for the enjoyment of all Australians – Indigenous and non- Indigenous. -

WESTERN AUSTRALIA. [Published by Authority

OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA. [Published by Authority. ] No. 32.] PERTH: FRIDAY, JULY 20. [1894. No. 5690.-C.S.0. No. 5697.-C.S.0. Parliament Summoned to Meet for Business. Gaol proclaimed at Broome. PROCLAMATION ~i!ltr;ttxlt ~llr;tmli1tl} On behalf of His Excellency SIR °0°,,° PROCLAMATION to fuit. WILLIABI CLEAVER FRANCIS ROBIN- i!i!hr;tmt ~llr;tmlill, "( On behalf of His Excellenoy SIR SON, Knight Grand Cross of the to (uit. .) VVILLIA~I CLEAVER E'RANCIS ROIlIN- J\'Iost Distinguished Order of Saint SON, Knight Grand Cross of the ALEX. C. ONSLOW, Most Distinguished Order of Saint Governo)"'s DClllt(y. 1\'Iiehael and Saint George, Governor ALEX, C. ONSLOW, and Commander-in-Chief in and over Governol"S Dcpnty. Michael and Saint George, Governor and Commander-in-Chiefin and over (L. s.) the Colony of vVestorn Australia (L. s.) the Colony of Western Australia and its Dependencies, &c., &c.,&c. and its Dependencies, &c., &c., &c. HEREAS under the provisions of "The ALEXANDER CAllIPBELL ONSLOW, Chief Justice of W Constitution Act, 1889," it is nmde lawful for the Governor of vVestern Australia for the time the said Colony, Governor's Deputy, by virtue being to fix the phtce and time for holding the first of the Ordinance 21 Victoria, No. 12, intituled "An and every other Session of the Legislative Council " Ordinance to extend and enlarge the provisions of and Legislative Assembly: Now THEREFORE I, " an Ordinance passed in the twelfth year of the ALEXANDER CAllIPBELL ONSLOW, Chief Justice of "reign of Her present JYlajesty, int.ituled 'An the said -

Our Western Land 1890 – 1939

Our Western Land 1890 - 1939 This is the second of four historical facts sheets prepared for Celebrate WA by Ruth Marchant James. The purpose of these documents is to present a brief and accurate timeline of the important dates and events in the history of Western Australia. 1890s 1892 SeptemBer – Bayley and Ford discovered gold The South-Western, Great Southern and at Fly Flat, Coolgardie. The news sparked a Eastern railways were completed. The huge goldrush. extension of the railway system resulted in many new townsites Being declared in 2 DecemBer – Alexander Forrest, explorer, previously undeveloped areas. financier and Brother of John Forrest, sworn in as Mayor of Perth. Copper found at Ravensthorpe. 1890 June – the first cattle shipment from the KimBerley district arrived at Fremantle from 17 June – Paddy Hannan, Dan O’Shea and DerBy. By 1893 almost 2000 head of cattle Thomas Flanagan pegged Hannan’s Reward were dispatched south annually. claim. The area was later known as Kalgoorlie. NovemBer – Fraser’s Mine, the largest in Southern Cross (registered as a company on 8 1892- 1893 OctoBer), paid shareholders the first dividend Smallpox epidemic in Perth resulted in a from gold in the colony. number of deaths and the establishment of 11 DecemBer – Ashburton goldfields quarantine camps. proclaimed. 29 DecemBer – John Forrest, memBer for the 1893 – 1902 Legislative AssemBly electorate of BunBury in The timBer industry experienced a Boom the new Government, sworn in By Governor period. New mill towns such as Waroona, Robinson as Colonial Treasurer. He assumed Mornington, Yarloop and Wellington were the courtesy title “Premier” and held that office established whilst existing mills, among them for more than ten years.