Along the Canning Stock Route

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Priorities for Western Australia April 2013 Keeping Western Australians on the Move

Federal priorities for Western Australia April 2013 Keeping Western Australians on the move. Federal priorities for Western Australia Western Australia’s rapid population growth coupled with its strongly performing economy is creating significant challenges and pressures for the State and its people. Nowhere is this more obvious than on the State’s road and public transport networks. Kununurra In March 2013 the RAC released its modelling of projected growth in motor vehicle registrations which revealed that an additional one million motorised vehicles could be on Western Australia’s roads by the end of this decade. This growth, combined with significant developments in Derby and around the Perth CBD, is placing increasing strain on an already Great Northern Hwy Broome Fitzroy Crossing over-stretched transport network. Halls Creek The continued prosperity of regional Western Australia, primarily driven by the resources sector, has highlighted that the existing Wickham roads do not support the current Dampier Port Hedland or future resources, Karratha tourism and economic growth, both in terms Exmouth of road safety and Tom Price handling increased Great Northern Highway - Coral Bay traffic volumes. Parabardoo Newman Muchea and Wubin North West Coastal Highway East Bullsbrook Minilya to Barradale The RAC, as the Perth Darwin National Highway representative of Great Eastern Mitchell Freeway extension Ellenbrook more than 750,000 Carnarvon Highway: Bilgoman Tonkin Highway Grade Separations Road Mann Street members, North West Coastal Hwy Mundaring Light Rail PERTH believes that a Denham Airport Rail Link strong argument Goldfields Hwy Fremantle exists for Western Australia to receive Tonkin Highway an increased share Kalbarri Leinster Extension of Federal funding Kwinana 0 20 Rockingham Kilometres for road and public Geraldton transport projects. -

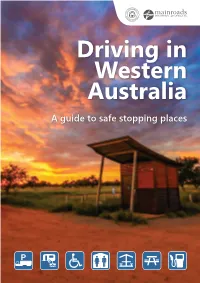

Driving in Wa • a Guide to Rest Areas

DRIVING IN WA • A GUIDE TO REST AREAS Driving in Western Australia A guide to safe stopping places DRIVING IN WA • A GUIDE TO REST AREAS Contents Acknowledgement of Country 1 Securing your load 12 About Us 2 Give Animals a Brake 13 Travelling with pets? 13 Travel Map 2 Driving on remote and unsealed roads 14 Roadside Stopping Places 2 Unsealed Roads 14 Parking bays and rest areas 3 Litter 15 Sharing rest areas 4 Blackwater disposal 5 Useful contacts 16 Changing Places 5 Our Regions 17 Planning a Road Trip? 6 Perth Metropolitan Area 18 Basic road rules 6 Kimberley 20 Multi-lingual Signs 6 Safe overtaking 6 Pilbara 22 Oversize and Overmass Vehicles 7 Mid-West Gascoyne 24 Cyclones, fires and floods - know your risk 8 Wheatbelt 26 Fatigue 10 Goldfields Esperance 28 Manage Fatigue 10 Acknowledgement of Country The Government of Western Australia Rest Areas, Roadhouses and South West 30 Driver Reviver 11 acknowledges the traditional custodians throughout Western Australia Great Southern 32 What to do if you breakdown 11 and their continuing connection to the land, waters and community. Route Maps 34 Towing and securing your load 12 We pay our respects to all members of the Aboriginal communities and Planning to tow a caravan, camper trailer their cultures; and to Elders both past and present. or similar? 12 Disclaimer: The maps contained within this booklet provide approximate times and distances for journeys however, their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Main Roads reserves the right to update this information at any time without notice. To the extent permitted by law, Main Roads, its employees, agents and contributors are not liable to any person or entity for any loss or damage arising from the use of this information, or in connection with, the accuracy, reliability, currency or completeness of this material. -

Ngaanyatjarra Central Ranges Indigenous Protected Area

PLAN OF MANAGEMENT for the NGAANYATJARRA LANDS INDIGENOUS PROTECTED AREA Ngaanyatjarra Council Land Management Unit August 2002 PLAN OF MANAGEMENT for the Ngaanyatjarra Lands Indigenous Protected Area Prepared by: Keith Noble People & Ecology on behalf of the: Ngaanyatjarra Land Management Unit August 2002 i Table of Contents Notes on Yarnangu Orthography .................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................................................ v Cover photos .................................................................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................................. v Summary.................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Canning Stock Route & Gunbarrel Highway

CANNING STOCK ROUTE & GUNBARREL HIGHWAY Tour & Tag Along Option Pat Mangan Join us on this fully guided 4WD small group adventure tour. Travel as a passenger in one of our 4WD vehicles or use your own 4WD Tag Along vehicle as you join our experienced guides exploring the contrasting and arid outback of Australia. Visit iconic & remote areas such as the Canning Stock Route & Gunbarrel Highway, see Uluru, Durba Springs, 2 night stay at Carnegie Station, Giles Meteorological Station, the “Haunted Well” – Well 37, Len Beadell’s Talawana Track & the Tanami Track - ending your adventure in Alice Springs. 21 Days Dep 15 Jun 2021 DAY 1: Tue 15 Jun ARRIVE AT AYERS ROCK RESORT T (-) Clients to have own travel arrangements to Ayers Rock, Northern Territory. Please check-in by 5:00pm where you will meet your crew and fellow passengers for a tour briefing. Overnight: Ayers Rock Campground • □ DAY 2: Wed 16 Jun AYERS ROCK - GILES 480km T (BLD) Depart this morning at 9:00am and pass by Ayers Rock and take a short walk into Olga Gorge before our journey west along the new Gunbarrel Highway to the WA border and beyond. Visit Lasseter's cave, where this exocentric miner camped after his alleged discovery of a reef of gold. Then on through the Petermann Ranges to WA and Giles. Overnight: Giles • □ DAY 3: Thu 17 Jun GILES – WARBURTON 180km T (BLD) A morning outside viewing of the Meteorological Station. See Beadell’s grader that opened up the network of outback roads in the 1950's and 60's including the infamous Gunbarrel Highway. -

4-H Canning Label Found at Under “State Fair” Or Located Below

DIVISION 6036 - 4-H FOOD PRESERVATION EXHIBITS—2016 Sandra Bastin – Food & Nutrition Specialist Martha Welch – 4-H Youth Development Specialist 1. Classes in Division: 861-865. 2. Number of Entries Permitted: a. County may submit ONE entry per class. b. A member may enter one class in the Food Preservation division. (This means: a member’s name should appear only one time on the county’s Food Preservation Division invoice sheet.) 3. General Rules: a. See “General Rules Applying to All 4-H Exhibitors in the Kentucky State Fair” at www.kystatefair.org Click on “Compete,” then “Premium Book”, then “4-H Exhibits.” b. Items must meet the requirements for the class; otherwise, the entry may be disqualified. c. Items entered must have been completed by the exhibitor within the current program year. d. The decision of the judges is final. 4. Unique Rules or Instructions: a. Recipes: Entries are to be made using recipes found in the 2016 4-H Fair Recipe Book at http://4- h.ca.uky.edu/content/food-and-nutrition or contact your county Extension agent for 4-H YD. b. Canned entries must be prepared from raw produce. c. Re-canning of commercially processed foods is not permitted. d. Helpful Information for the following classes can be found on the National Center for Home Food Preservation website. e. Jars not processed by the correct method will not be judged. Open kettle processing is not acceptable for any product. f. Jars must be clear, clean STANDARD jars specifically designed for home canning. If mayonnaise or similar non-standard jars are used, the product will not be judged or awarded a premium. -

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

Western Australia – Permits and Permissions Required to Access Indigenous and Other Lands, Including National Parks

Western Australia – Permits and permissions required to access indigenous and other lands, including national parks General: Quite a number of transit permits for aboriginal lands in WA are able to be issued by the Aboriginal Lands Trust of WA. (N.B.: The Aboriginal Lands Trust has no involvement whatever in the issuing of permits for the Canning Stock Route – for Canning information and Permits see below under the heading of Canning Stock Route). The Trust is a part of the Department of Indigenous Affairs. Applications can be made on-line at www.dia.wa.gov.au and simply follow the prompts. The web site contains a lot of excellent information including maps showing the specific areas and tracks where Permits are required and whether the Trust or a Land Council issues them. The conditions under which permits can be gained via an automated on-line process are also explained. Once you log on to the web site, click on the “Entering Aboriginal Land” button on the left side of the Home Page and read all of the information under the nominated four (4) headings BEFORE applying on-line. The maps showing the tracks and whether DIA or a Land Council, etc., issues them can be found under the “Travel Information” heading. About half way down that page is a map of WA showing the Land Council areas; simply click on the area you want to visit. The Trust can be contacted at: The Permits Officer, Aboriginal Lands Trust, PO Box 7770, Cloisters Square, Perth, WA 6850. Telephone (08) 9235 8000 or Fax (08) 9235 8088. -

Characterization of a Biodegradable Starch Based Film

Characterization of a biodegradable starch based film Application on the preservation of fresh spinach Inês Antunes Gonzalez Dissertation to obtain the degree of master in Food Engineering Advisors: Doutor Vítor Manuel Delgado Alves Doutora Margarida Moldão Martins Doutora Elizabeth da Costa Neves Fernandes de Almeida Duarte Jury: President: Doutora Maria Luísa Louro Martins, Professora Auxiliar do Instituto Superior de Agronomia da Universidade de Lisboa Members: Doutora Isabel Maria Rôla Coelhoso, Professora Auxiliar da Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa Doutor Vítor Manuel Delgado Alves, Professor Auxiliar do Instituto Superior de Agronomia da Universidade de Lisboa 2016 Acknowledgments Apesar de a dissertação de mestrado ser um trabalho individual, considero que o seu sucesso está inteiramente relacionado com fatores independente do desempenho pessoal. Apesar da minha grande dedicação neste projeto, teria sido uma jornada bastante difícil de percorrer sem a ajuda e motivação que obtive de várias partes, às quais não podia deixar de destacar o meu agradecimento. Em primeiro lugar, destaco um profundo agradecimento ao professor Vítor Manuel Delgado Alves, quer pelo apoio e disponibilidade na realização dos ensaios laboratoriais, quer na motivação e interesse incutidos no projeto, principalmente aquando as várias barreiras que lhe surgiram. Seguidamente gostaria de agradecer à Professora Elizabeth da Costa Neves Fernandes de Almeida Duarte, pela sugestão do projeto, bem como à Silvex por possibilitar a sua concretização. Agradeço também à professora Margarida Moldão Martins, pelo grande auxílio e aconselhamento ao longo de todas as fases do estudo, especialmente no que respeita ao planeamento da avaliação da aplicação do filme na conservação do espinafre. -

Biodegradable Packaging Materials from Animal Processing Co-Products and Wastes: an Overview

polymers Review Biodegradable Packaging Materials from Animal Processing Co-Products and Wastes: An Overview Diako Khodaei, Carlos Álvarez and Anne Maria Mullen * Department of Food Quality and Sensory Science, Teagasc Food Research Centre, Ashtown, Dublin, Ireland; [email protected] (D.K.); [email protected] (C.Á.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +353-(1)-8059521 Abstract: Biodegradable polymers are non-toxic, environmentally friendly biopolymers with con- siderable mechanical and barrier properties that can be degraded in industrial or home composting conditions. These biopolymers can be generated from sustainable natural sources or from the agri- cultural and animal processing co-products and wastes. Animals processing co-products are low value, underutilized, non-meat components that are generally generated from meat processing or slaughterhouse such as hide, blood, some offal etc. These are often converted into low-value products such as animal feed or in some cases disposed of as waste. Collagen, gelatin, keratin, myofibrillar proteins, and chitosan are the major value-added biopolymers obtained from the processing of animal’s products. While these have many applications in food and pharmaceutical industries, a sig- nificant amount is underutilized and therefore hold potential for use in the generation of bioplastics. This review summarizes the research progress on the utilization of meat processing co-products to fabricate biodegradable polymers with the main focus on food industry applications. In addition, the factors affecting the application of biodegradable polymers in the packaging sector, their current industrial status, and regulations are also discussed. Citation: Khodaei, D.; Álvarez, C.; Mullen, A.M. Biodegradable Keywords: biodegradable polymers; packaging materials; meat co-products; animal by-products; Packaging Materials from Animal protein films Processing Co-Products and Wastes: An Overview. -

Following the Camel and Compass Trail One Hundred Years On

Following the Camel and Compass Trail One Hundred Years on Ken LEIGHTON1 and James CANNING2, Australia Key words: Historical surveying, early Indigenous contact, Canning Stock Route SUMMARY In this paper, the authors Ken Leighton and James Canning tell the story of one of the most significant explorations in the history of Western Australia, carried out in arduous conditions by a dedicated Surveyor and his team in 1906. The experiences of the original expedition into remote Aboriginal homelands and the subsequent development of the iconic “Canning Stock Route” become the subject of review as the authors investigate the region and the survey after the passage of 100 years. Employing a century of improvements in surveying technology, the authors combine desktop computations with a series of field survey expeditions to compare survey results from the past and present era, often with surprising results. History Workshop - Day 2 - The World’s Greatest Surveyors - Session 4 1/21 Ken Leighton and James Canning Following the camel and compass trail one hundred years on (4130) FIG Congress 2010 Facing the Challenges – Building the Capacity Sydney Australia, 9 – 10 April 2010 Following the Camel and Compass Trail One Hundred Years on Ken LEIGHTON1 and James CANNING2, Australia ABSTRACT In the mere space of 100 years, the world of surveying has undergone both incremental and quantum leaps. This fact is exceptionally highlighted by the recent work of surveyors Ken Leighton and James Canning along Australia’s most isolated linear landscape, the Canning Stock Route. Stretching 1700 kilometres through several remote Western Australian deserts, this iconic path was originally surveyed by an exploration party in 1906, led by a celebrated Government Surveyor; Alfred Wernam Canning. -

Martu Paint Country

MARTU PAINT COUNTRY THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF COLOUR AND AESTHETICS IN WESTERN DESERT ROCK ART AND CONTEMPORARY ACRYLIC ART Samantha Higgs June 2016 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University Copyright by Samantha Higgs 2016 All Rights Reserved Martu Paint Country This PhD research was funded as part of an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Project, the Canning Stock Route (Rock art and Jukurrpa) Project, which involved the ARC, the Australian National University (ANU), the Western Australian (WA) Department of Indigenous Affairs (DIA), the Department of Environment and Climate Change WA (DEC), The Federal Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA, now the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Population and Communities) the Kimberley Land Council (KLC), Landgate WA, the Central Desert Native Title Service (CDNTS) and Jo McDonald Cultural Heritage Management Pty Ltd (JMcD CHM). Principal researchers on the project were Dr Jo McDonald and Dr Peter Veth. The rock art used in this study was recorded by a team of people as part of the Canning Stock Route project field trips in 2008, 2009 and 2010. The rock art recording team was led by Jo McDonald and her categories for recording were used. I certify that this thesis is my own original work. Samantha Higgs Image on title page from a painting by Mulyatingki Marney, Martumili Artists. Martu Paint Country Acknowledgements Thank you to the artists and staff at Martumili Artists for their amazing generosity and patience. -

Slim Dusty Movie Music Credits

Music Production Rod Coe (Cast, singing) Slim Dusty Joy McKean Anne Kirkpatrick and the Travelling Country Band David Kirkpatrick Gordon Parsons Buck Taylor (Tail credits) The Travelling Country Band Lead Guitar Mick Reid Fiddle and Mandolin Mike Kerin Drums Alan Hockley Banjo and Dobro Ian Simpson Pedal Steel Michel Rose Bass Guitar Bill Graham Location Sound Supervisor Paul Clark Boom Operator/ Recordist Steve Haggerty AAV Technical Supervision Steve Pyle Music Engineer Scott Heming Sound Assistant Chris Piper Concert Sound Mixer Clive Jones Featured Music Where Country is Barry "Morchi" Moyses The Band Played on Traditional Song for the Aussies Slim Dusty Aristocrat Tex Morton Simmo's Tune Ian Simpson Old Sunlander Van Joy McKean Anne Kirkpatrick G. Paige Losin' my Blues Tonight Slim Dusty Wind up Gramophone Joy McKean Trouble Joy McKean Walk a Country Mile Joy McKean Old Feller Joy McKean Drownin' my Blues Slim Dusty My Final Song Slim Dusty When the Rain Tumbles down in July Slim Dusty Camoweal "Mack" Cormack So many Ballads to Play Slim Dusty The Man from the Northland Buck Taylor Old Time Country Halls Slim Dusty Biggest Disappointment Joy McKean Lights on the Hill Joy McKean Gymkhana Yodel Joy McKean Stay Away from me Slim Dusty Keep the Love Light Shining Joy McKean Country Revival Slim Dusty The Isa Rodeo Slim Dusty Stan Coster Rough Riders Slim Dusty A. E. Brooks Cunnamulla Feller Stan Coster Isa R. Ryan Plains of Peppimenarti Slim Dusty How will I go with him Mate "Mack" Cormack Just Rollin' Slim Dusty Pushin' Time Slim Dusty A. E.