Depaul Symphony Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TOCC0557DIGIBKLT.Pdf

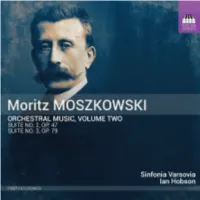

MORITZ MOSZKOWSKI: ORCHESTRAL MUSIC, VOLUME TWO by Martin Eastick History has not served Moszkowski well. Even before his death in 1925, his star had been on the wane for some years as the evolving ‘Brave New World’ took hold after the Great War in 1918: there was little or no demand for what Moszkowski once had to offer and the musical sensitivities he represented. His name did live on to a limited extent, with the odd bravura piano piece relegated to the status of recital encore, and his piano duets – especially the Spanish Dances – continuing to be favoured in the circles of home music-making. But that was about the limit of his renown until, during the late 1960s, there gradually awoke an interest in nineteenth-century music that had disappeared from the repertoire – and from people’s awareness – and the composers who had been everyday names during their own lifetime, Moszkowski among them. Initially, this ‘Romantic Revival’ was centred mainly on the piano, but it gradually diversified to music in all its forms and continues to this day. Only very recently, though, has attention been given to Moszkowski as a serious composer of orchestral music – with the discovery and performance in 2014 of his early but remarkable ‘lost’ Piano Concerto in B minor, Op. 3, providing an ideal kick-start,1 and the ensuing realisation that here was a composer worthy of serious consideration who had much to offer to today’s listener. In 2019 the status of Moszkowski as an orchestral composer was ramped upwards with the release of the first volume in this Toccata Classics series, featuring his hour-long, four-movement symphonic poem Johanna d’Arc, Op. -

Connected by Music Dear Friends of the School of Music

sonorities 2021 The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music Connected by Music Dear Friends of the School of Music, Published for the alumni and friends of the ast year was my first as director of the school and as a member School of Music at the University of Illinois at of the faculty. It was a year full of surprises. Most of these Urbana-Champaign. surprises were wonderful, as I was introduced to tremendously The School of Music is a unit of the College of Lcreative students and faculty, attended world-class performances Fine + Applied Arts and has been an accredited on campus, and got to meet many of you for the first time. institutional member of the National Association Nothing, however, could have prepared any of us for the of Schools of Music since 1933. changes we had to make beginning in March 2020 with the onset of COVID-19. Kevin Hamilton, Dean of the College of Fine + These involved switching our spring and summer programs to an online format Applied Arts with very little notice and preparing for a fall semester in which some of our activi- Jeffrey Sposato, Director of the School of Music ties took place on campus and some stayed online. While I certainly would never Michael Siletti (PhD ’18), Editor have wished for a year with so many challenges, I have been deeply impressed by Design and layout by Studio 2D the determination, dedication, and generosity of our students, faculty, alumni, and On the cover: Members of the Varsity Men’s Glee friends. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1980

- wm /j ^CHAM?^ iir ?**»»« hl ,(t«ll <Ma4^4m^mf7$f i$i& Vs^Qp COGNAC W****** B r jfi>AV., RY y -^^COgJi INf :<k champacni: < THE FIRST NAME IN COGNAC SINCE 1724 /ELY F.INI CHAYf PAGNJi COGNAC: IKUV1 IHI TWO "PREMIERS CRUS" OF fHFi COGNAC REGION BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA A Music Director \K , vft Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Sir Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor Ninety-Ninth Season, 1979-80 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Talcott M. Banks, Chairman Nelson J. Darling, Jr., President Philip K. Allen, Vice-President Sidney Stoneman, Vice-President Mrs. Harris Fahnestock, Vice-President John L. Thorndike, Vice-President Roderick M. MacDougall, Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Archie C. Epps III Thomas D. Perry, Jr. Allen G. Barry E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Irving W. Rabb Leo L. Beranek Edward M. Kennedy Paul C. Reardon Mrs. John M. Bradley George H. Kidder David Rockefeller, Jr. George H.A. Clowes, Jr. Edward G. Murray Mrs. George Lee Sargent Abram T. Collier Albert L. Nickerson John Hoyt Stookey Trustees Emeriti Richard P. Chapman John T. Noonan Mrs. James H. Perkins Administration of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Thomas W. Morris General Manager Peter Gelb Gideon Toeplitz Daniel R. Gustin Assistant Manager Orchestra Manager Assistant Manager Joseph M. Hobbs Walter D. Hill William Bernell Director of Director of Assistant to the Development Business Affairs General Manager Caroline E. Hessberg Dorothy Sullivan Anita R. Kurland Promotion Administrator Controller of Coordinator Youth Activities Joyce M. Snyder Richard Ortner Elisabeth Quinn Development Assitant Administrator, Director of Coordinator Berkshire Music Center Volunteer Services Elizabeth Dunton James E. -

Press Release of the 2019 Salzburg Festival Grigory Sokolov & the Salzburg Festival Present ALEXANDRA DOVGAN (SF, 1 July

Press Release of the 2019 Salzburg Festival Grigory Sokolov & the Salzburg Festival present ALEXANDRA DOVGAN (SF, 1 July 2019) Born in 2007, Alexandra Dovgan brings an exceptional talent to the piano. Grigory Sokolov and the Salzburg Festival present the 11-year-old pianist in a concert on Wednesday, 31 July at 3 pm at the Main Auditorium of the Mozarteum Foundation. Grigory Sokolov says about Alexandra Dovgan: “This is one of those rare occasions. The eleven-year-old pianist Alexandra Dovgan can hardly be called a wonder child, for while this is a wonder, it is not child’s play. What one hears is a performance by a grown-up individual and a person. It is a special pleasure for me to commend the art of her remarkable music teacher, Mira Marchenko. Yet there are things that cannot be taught and learned. Alexandra Dovgan’s talent is exceptionally harmonious. Her playing is honest and concentrated. I predict a great future for her…” Free tickets to her concert are available starting on 6 July at the Salzburg Festival Shop. Alexandra Dovgan © Oscar Tursunov Grigory Sokolov & the Salzburg Festival present ALEXANDRA DOVGAN Wednesday, 31 July, 3 pm Mozarteum Foundation – Main Auditorium Programme DOMENICO SCARLATTI Sonata for harpsichord in D major, K 436 DOMENICO SCARLATTI Sonata for harpsichord in F minor, K 466 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Sonata for piano No. 10 in G major, Op. 14/2 JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Preludio, Gavotte and Gigue from the Partita for violin solo No. 3 in E major, BWV 1006 (Piano arrangement by Sergei Rachmaninoff) SERGEI RACHMANINOFF “Margaritki” (Daisies) from 6 Romances, Op. -

2/1-Spaltig, Mit Einrückung Ab Titelfeld

Landesarchiv Berlin E Rep. 061-16 Nachlass Rudolf Mosse Findbuch Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort II Verzeichnungseinheiten 1 Behörden und Institutionen 151 Firmenindex 151 Personenindex 151 Sachindex 165 Vereine und Vereinigungen 170 E Rep. 061-16 Nachlass Rudolf Mosse Vorwort I. Biographie Rudolf Mosse wurde am 9. Mai 1843 in Grätz (Posen) geboren. Nach der Schulzeit ging er 1861 für eine Buchhandelslehre nach Berlin, wo er zunächst im Verlag des "Kladderadatsch" mitarbeitete. Wenig später übernahm er in Leipzig die Geschäftsleitung des "Telegraphen" und wirkte außerdem so erfolgreich in der Anzeigenaquisition der "Gartenlaube", dass man ihm eine Teilhaberschaft anbot. Mosse schlug das Angebot jedoch aus und zog 1866 wieder nach Berlin, wo er 1867 die "Annoncen-Expedition Rudolf Mosse" gründete. Obwohl dieses erste Geschäft bankrott ging, gelang 1870/71 ein zweiter Versuch. Mosse gründete ergänzend dazu 1872 seine erste Zei- tung, das "Berliner Tageblatt", mit bedeutendem Inseratenteil. Er pachtete außerdem Insera- tenteile von anderen Zeitungen und Zeitschriften, um sie ausschließlich mit Inseraten seiner Vermittlung zu bestücken. Mosse baute sein Unternehmen durch die Gründung eines Ver- lags aus; 1889 gründete er gemeinsam mit Emil Cohn die "Berliner Morgenpost" und über- nahm 1904 die "Berliner Volkszeitung". Der erfolgreiche Verleger konnte mit seinen Unternehmen ein bedeutendes Vermögen er- werben. Vor Beginn des Ersten Weltkriegs galt Mosse als Berlins größter Steuerzahler. Ru- dolf Mosse war verheiratet mit Emilie, geb. Loewenstein (1851-1924). 1893 adoptierte er die fünfjährige Felicia. Rudolf Mosse war eine gesellschaftlich außerordentlich stark engagierte Persönlichkeit. Er wirkte in zahlreichen Ausschüssen, Vereinen und Gremien mit. Gemeinsam mit seiner Frau betätigte er sich an gemeinnützigen Projekten. Emilie Mosse gründete beispielsweise 1888 den ersten Mädchenhort in Berlin. -

Curtis Institute of Music Duo-Art Piano Roll Collection ARS.0215

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8ng4z0b Online items available Curtis Institute of Music Duo-Art Piano Roll Collection ARS.0215 Benjamin E. Bates Archive of Recorded Sound [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/ars Curtis Institute of Music Duo-Art ARS.0215 1 Piano Roll Collection ARS.0215 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Archive of Recorded Sound Title: Curtis Institute of Music Duo-Art Piano Roll Collection source: Groman, Richard source: Taylor, Robert M. source: Hofmann, Josef, 1876-1957 Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0215 Physical Description: 14 box(es)(230) piano roll(s) Date (inclusive): 1913-1932 Content Description This collection consists of Duo-Art piano rolls once curated by Josef Hofmann, pianist and director of the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, from 1926 to 1938. His performances of Beethoven, Chopin, and his own compositions are included. Other notable pianists include Harold Bauer, Alfred Cortot, Guiomar Novaes, Ignace Jan Paderewski, and Serge Prokofieff among others. Curator's biography "Josef Casimir Hofmann, (born Jan. 20, 1876, Podgorze, near Kraków, Pol.—died Feb. 16, 1957, Los Angeles), Polish-born American pianist, especially noted for his glittering performances of the music of Frédéric Chopin. He gave his first concert at the age of 6 and toured the United States at 11. Later he studied with two leading pianists of the late 19th century, Moritz Moszkowski and Anton Rubinstein. He resumed his public career at 18 and from 1898 lived mainly in the United States. From 1926 to 1938 he was director of the Curtis Institute of Music, Philadelphia. -

The Piano Etudes of David Rakowski

THE PIANO ETUDES OF DAVID RAKOWSKI I-Chen Yeh A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS December 2010 Committee: Laura Melton, Advisor Sara Worley Graduate Faculty Representative Per F. Broman Robert Satterlee © 2010 I-Chen Yeh All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Laura Melton, Advisor Since the early history of piano music the etude has played an important role in the instrument’s repertoire. The genre has grown from technical exercises to virtuosic concert pieces. During the twentieth century, new movements in music were reflected in the etudes of Debussy, Stravinsky and Messiaen, to mention a few. In the past fifty years, Bolcom and Ligeti have continued this trend, taking the piano etude to yet another level. Their etudes reflect the aesthetics and process of modernist and postmodernist composition, featuring complex rhythms, new techniques in pitch and harmonic organization, a variety of new extended techniques, and an often-unprecedented level of difficulty. David Rakowski is a prolific composer of contemporary piano etudes, having completed a cycle of one hundred piano etudes during the past twenty-two years. By mixing his own modernist aesthetic with jazz, rock, and pop-culture influences, Rakowski has created a set of etudes that are both challenging to the pianist and approachable for the audience. The etudes have drawn the attention of several leading pianists in the contemporary field, most notably Marilyn Nonken and Amy Briggs, who are currently recording the entire set. Because of pianistic difficulty, approachability for the listener, and interest of noted pianists, Rakowski’s etudes seem destined for recognition in the contemporary standard repertoire. -

Competition of Polish Music in Rzeszów the Stanisław Moniuszko International Competition of Polish Music in Rzeszów 20 – 27 September 2019

WWW.KONKURSMUZYKIPOLSKIEJ.PL THE STANISŁAW MONIUSZKO INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION OF POLISH MUSIC IN RZESZÓW THE STANISŁAW MONIUSZKO INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION OF POLISH MUSIC IN RZESZÓW 20 – 27 SEPTEMBER 2019 The Stanisław Moniuszko International Competition of Polish Music in Rzeszów is a new cultural initiative whose purpose is to promote Polish music around the world and make the listeners realise the quality and significance of the musical legacy of Stanisław Moniuszko and many other distinguished Polish composers from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. MISSION AND OBJECTIVES OF THE COMPETITION The Stanisław Moniuszko International Competition of Polish Music (Międzynarodowy Konkurs Muzyki Polskiej im. Stanisława Moniuszki) in Rzeszów has been initiated in order to promote that part of the great legacy of nineteenth and twentieth century Polish music which has been forgotten or, for a variety of reasons, has been less popular in concert practice. Its other objective is to present rediscovered works to the general public and provide this unjustly neglected legacy with appropriate analyses and new editions. The Competition also endeavours to promote talented musicians who are willing to include lesser-known works written by Polish composers in their concert programmes. The final aim of the Competition is to disseminate information about Polish artistic events addressed to the international recipients. BASIC PRINCIPLES The Stanisław Moniuszko International Competition of Polish Music in Rzeszów will be organised on a biennial basis and will be intended for a variety of different sets of performers. The first edition of the Competition will be divided into two distinct categories: one for piano and the other for chamber ensembles. -

VOX Catalogue Numbers — 3000 to 3999: Male Solo Voices Discography Compiled by Christian Zwarg for GHT Wien Diese Diskographie Dient Ausschließlich Forschungszwecken

VOX Catalogue Numbers — 3000 to 3999: Male Solo Voices Discography compiled by Christian Zwarg for GHT Wien Diese Diskographie dient ausschließlich Forschungszwecken. Die beschriebenen Tonträger stehen nicht zum Verkauf und sind auch nicht im Archiv des Autors oder der GHT vorhanden. Anfragen nach Kopien der hier verzeichneten Tonaufnahmen können daher nicht bearbeitet werden. Sollten Sie Fehler oder Auslassungen in diesem Dokument bemerken, freuen wir uns über eine Mitteilung, um zukünftige Updates noch weiter verbessern und ergänzen zu können. Bitte senden Sie Ihre Ergänzungs- und Korrekturvorschläge an: [email protected] This discography is provided for research purposes only. The media described herein are neither for sale, nor are they part of the author's or the GHT's archive. Requests for copies of the listed recordings therefore cannot be fulfilled. Should you notice errors or omissions in this document, we appreciate your notifying us, to help us improve future updates. Please send your addenda and corrigenda to: [email protected] Vox 3000 D25 master 26 B 1921.10.01→11 GER: Berlin, Vox-Haus, W.9, Potsdamer Str. 4 Solang' a junger Wein is — Wiener Walzerlied (M + W: Ralph Benatzky) …?… (MD). — (orchestra). Erik Wirl (tenor). master 27 B 1921.10.01→11 GER: Berlin, Vox-Haus, W.9, Potsdamer Str. 4 Im Prater blüh'n wieder die Bäume — Wiener Lied (Robert Stolz, op.247 / Kurt Robitschek) …?… (MD). — (orchestra). Erik Wirl (tenor). Vox 3001 D25 master 24 B 1921.10.01→11 GER: Berlin, Vox-Haus, W.9, Potsdamer Str. 4 DER LETZTE ROCK (Hugo Schenk / Oskar Hofmann) Die Luft vom Wienerwald — Lied [Walzer] …?… (MD). -

5069883-Deb527-5060113445728

MORITZ MOSZKOWSKI: PIANO MUSIC, VOLUME ONE by Martin Eastick ‘After Chopin, Moszkowski best understands how to write for the piano, and his writing embraces the whole gamut of piano technique’.1 Paderewski’s oft-repeated endorsement of his fellow countryman’s reputation offers an idea of the high esteem in which Moszkowski was once held – certainly at the pinnacle of his achievement during the closing years of the nineteenth century. The more sober artistic climate of the early 21st seems to have less time for music now regarded as the frivolity of a more innocent age. Moszkowski’s piano music had indeed been very popular, but a gradual decline set in after the cultural and social changes brought about by the Great War. Just occasionally, during the past hundred or so years since his death in 1925, the odd Moszkowski bon-bon – perhaps his ‘Étincelles’ (the sixth of his Huit Morceaux Caractéristiques, Op. 36), or the Caprice espagnole, Op. 37 – has provided a recital encore by some enterprising pianist. Moszkowski came from a wealthy Polish-Jewish family which had settled in Breslau (now the Polish city of Wrocław, but then the capital of Silesia in East Prussia) in 1854, the year of his birth. Having displayed a natural talent for music from an early age, and with some basic home tuition, he began his formal musical education in 1865, after his family’s relocation to Dresden. A further family move, to Berlin, in 1869, enabled Moszkowski to continue his musical education – first at Julius Stern’s Conservatorium (which still exists, as part of the Faculty of Music of the Berlin University of the Arts), where he studied piano with the composer- pianist Eduard Franck (1817–93) and composition with the famous theoretician and composer Friedrich Kiel (1821–85). -

A History of the Development of Solo Piano Recitals with a Comparison of Golden Age and Modern- Day Concert Programs at Carnegie Hall by © 2017 Rosy Ge D

The Art of Recital Programming: A History of the Development of Solo Piano Recitals with a Comparison of Golden Age and Modern- Day Concert Programs at Carnegie Hall By © 2017 Rosy Ge D. M. A., University of Kansas, 2017 M. M., Indiana University, 2013 B. M., Oberlin College and Conservatory, 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in the School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance. Chair: Steven Spooner Scott McBride Smith Colin Roust Joyce Castle Robert Ward Date Defended: 24 August 2017 ii The dissertation committee for Rosy Ge certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Art of Recital Programming: A History of the Development of Solo Piano Recitals with a Comparison of Golden Age and Modern- Day Concert Programs at Carnegie Hall Chair: Steven Spooner Date Approved: 24 August 2017 iii ABSTRACT The art of recital programming is a never-ending discovery, and rediscovery of hidden gems. Many things go in and out of fashion, but the core composers and repertoire played on piano recitals have remained the same. From antiquity to the twenty-first century, pianists have access to over tens of thousands original and arranged works for the keyboard, yet less than one-tenth of them are considered to be in the standard performance canon. From this, a fascinating question forms: why are pianists limiting themselves to such narrow repertoire? Many noted pianists of the twentieth and twenty-first century specialize in a certain composer or style. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Reassessing a Legacy: Rachmaninoff in America, 1918–43 A dissertation submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2008 by Robin S. Gehl B.M., St. Olaf College, 1983 M.A., University of Minnesota, 1990 Advisor: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ABSTRACT A successful composer and conductor, Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) fled Russia at the time of the Bolshevik Revolution never to return. Rachmaninoff, at the age of forty-four, transformed himself by necessity into a concert pianist and toured America for a quarter of a century from 1918 until his death in 1943, becoming one of the greatest pianists of the day. Despite Rachmaninoff‘s immense talents, musicologists have largely dismissed him as a touring virtuoso and conservative, part-time composer. Rather than using mid-twentieth-century paradigms that classify Rachmaninoff as a minor, post-Romantic, figure, a recent revisionist approach would classify Rachmaninoff as an innovator. As one of the first major performer-composers in America to embrace recording and reproducing technology, along with the permanence and repetition it offered, Rachmaninoff successfully utilized mass media for twenty-five years. Already regarded as a conductor and composer of appealing music, Rachmaninoff extended his fame by recording and performing his own works, and those of others.