CHOPIN and HIS WORLD August 11–13 and 17–20, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

Canções E Modinhas: a Lecture Recital of Brazilian Art Song Repertoire Marcía Porter, Soprano and Lynn Kompass, Piano

Canções e modinhas: A lecture recital of Brazilian art song repertoire Marcía Porter, soprano and Lynn Kompass, piano As the wealth of possibilities continues to expand for students to study the vocal music and cultures of other countries, it has become increasingly important for voice teachers and coaches to augment their knowledge of repertoire from these various other non-traditional classical music cultures. I first became interested in Brazilian art song repertoire while pursuing my doctorate at the University of Michigan. One of my degree recitals included Ernani Braga’s Cinco canções nordestinas do folclore brasileiro (Five songs of northeastern Brazilian folklore), a group of songs based on Afro-Brazilian folk melodies and themes. Since 2002, I have been studying and researching classical Brazilian song literature and have programmed the music of Brazilian composers on nearly every recital since my days at the University of Michigan; several recitals have been entirely of Brazilian music. My love for the music and culture resulted in my first trip to Brazil in 2003. I have traveled there since then, most recently as a Fulbright Scholar and Visiting Professor at the Universidade de São Paulo. There is an abundance of Brazilian art song repertoire generally unknown in the United States. The music reflects the influence of several cultures, among them African, European, and Amerindian. A recorded history of Brazil’s rich music tradition can be traced back to the sixteenth-century colonial period. However, prior to colonization, the Amerindians who populated Brazil had their own tradition, which included music used in rituals and in other aspects of life. -

COCKEREL Education Guide DRAFT

VICTOR DeRENZI, Artistic Director RICHARD RUSSELL, Executive Director Exploration in Opera Teacher Resource Guide The Golden Cockerel By Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov Table of Contents The Opera The Cast ...................................................................................................... 2 The Story ...................................................................................................... 3-4 The Composer ............................................................................................. 5-6 Listening and Viewing .................................................................................. 7 Behind the Scenes Timeline ....................................................................................................... 8-9 The Russian Five .......................................................................................... 10 Satire and Irony ........................................................................................... 11 The Inspiration .............................................................................................. 12-13 Costume Design ........................................................................................... 14 Scenic Design ............................................................................................... 15 Q&A with the Queen of Shemakha ............................................................. 16-17 In The News In The News, 1924 ........................................................................................ 18-19 -

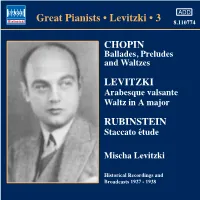

Print 110774Bk Levitzki

110774bk Levitzki 8/7/04 8:02 pm Page 5 Mischa Levitzki: Piano Recordings Vol. 3 Also available on Naxos ADD Gramophone Company Ltd., 1927-1933 RACHMANINOV: CHOPIN: @ Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5 3:22 Great Pianists • Levitzki • 3 8.110774 1 Prelude in C major, Op. 28 0:55 Recorded 21st November 1929 2 Prelude in A major, Op. 28, No. 7 0:55 Matrix Cc 18200-1a; Cat. D 1809 3 Prelude in F major, Op. 28, No. 23 1:24 Recorded 21st November 1929 RCA Victor, 1938 Matrix Bb 18113-3a; Cat.DA1223 LEVITZKI: 4 Waltz No. 8 in A flat major, Op. 64, No. 3 3:00 # Waltz in A major, Op. 2 1:46 CHOPIN Recorded 19th November 1928 Recorded 5th May 1938; Matrix Cc 14770-1; Cat.ED18 Matrices BS 023101-1, BS 023101-1A (NP), Ballades, Preludes BS 023101-2, BS 023101-2A (NP); Cat. 2008-A 5 Waltz No. 11 in G flat major, $ Arabesque valsante, Op. 6 3:23 and Waltzes Op. 70, No. 1 2:26 Recorded 5th May 1938; Recorded 19th November 1928 Matrices BS 023100-1, BS 023100-1A (NP), Matrix Cc 14769-3; Cat.ED18 BS 023100-2, BS 023100-2A (NP), BS 023100-3, 6 Ballade No. 3 in A flat major, Op. 47 6:26 BS023100-3A (NP); Cat. 2008-B Recorded 22nd November 1928 Broadcasts LEVITZKI Matrices Bb 11786-5 and 11787-5; Cat.EW64 26th January, 1935: 7 Nocturne No. 5 in F sharp major, CHOPIN: Arabesque valsante Op. 15, No. -

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings of the Year 2018 This

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings Of The Year 2018 This is the fifteenth year that MusicWeb International has asked its reviewing team to nominate their recordings of the year. Reviewers are not restricted to discs they had reviewed, but the choices must have been reviewed on MWI in the last 12 months (December 2017-November 2018). The 130 selections have come from 25 members of the team and 70 different labels, the choices reflecting as usual, the great diversity of music and sources - I say that every year, but still the spread of choices surprises and pleases me. Of the selections, 8 have received two nominations: Mahler and Strauss with Sergiu Celibidache on the Munich Phil choral music by Pavel Chesnokov on Reference Recordings Shostakovich symphonies with Andris Nelsons on DG The Gluepot Connection from the Londinium Choir on Somm The John Adams Edition on the Berlin Phil’s own label Historic recordings of Carlo Zecchi on APR Pärt symphonies on ECM works for two pianos by Stravinsky on Hyperion Chandos was this year’s leading label with 11 nominations, significantly more than any other label. MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR In this twelve month period, we published more than 2400 reviews. There is no easy or entirely satisfactory way of choosing one above all others as our Recording of the Year, but this year the choice was a little easier than usual. Pavel CHESNOKOV Teach Me Thy Statutes - PaTRAM Institute Male Choir/Vladimir Gorbik rec. 2016 REFERENCE RECORDINGS FR-727 SACD The most significant anniversary of 2018 was that of the centenary of the death of Claude Debussy, and while there were fine recordings of his music, none stood as deserving of this accolade as much as the choral works of Pavel Chesnokov. -

10-26-2019 Manon Mat.Indd

JULES MASSENET manon conductor Opera in five acts Maurizio Benini Libretto by Henri Meilhac and Philippe production Laurent Pelly Gille, based on the novel L’Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut set designer Chantal Thomas by Abbé Antoine-François Prévost costume designer Saturday, October 26, 2019 Laurent Pelly 1:00–5:05PM lighting designer Joël Adam Last time this season choreographer Lionel Hoche revival stage director The production of Manon was Christian Räth made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund general manager Peter Gelb Manon is a co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; jeanette lerman-neubauer Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Teatro music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin alla Scala, Milan; and Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse 2019–20 SEASON The 279th Metropolitan Opera performance of JULES MASSENET’S manon conductor Maurizio Benini in order of vocal appearance guillot de morfontaine manon lescaut Carlo Bosi Lisette Oropesa* de brétigny chevalier des grieux Brett Polegato Michael Fabiano pousset te a maid Jacqueline Echols Edyta Kulczak javot te comte des grieux Laura Krumm Kwangchul Youn roset te Maya Lahyani an innkeeper Paul Corona lescaut Artur Ruciński guards Mario Bahg** Jeongcheol Cha Saturday, October 26, 2019, 1:00–5:05PM This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from its founding sponsor, The Neubauer Family Foundation. Digital support of The Met: Live in HD is provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies. The Met: Live in HD series is supported by Rolex. -

Chopin: Visual Contexts

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology g, 2011 © Department of Musicology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland JACEK SZERSZENOWICZ (Łódź) Chopin: Visual Contexts ABSTRACT: The drawings, portraits and effigies of Chopin that were produced during his lifetime later became the basis for artists’ fantasies on the subject of his work. Just after the composer’s death, Teofil Kwiatkowski began to paint Bal w Hotel Lambert w Paryżu [Ball at the Hotel Lambert in Paris], symbolising the unfulfilled hopes of the Polish Great Emi gration that Chopin would join the mission to raise the spirit of the nation. Henryk Siemiradzki recalled the young musician’s visit to the Radziwiłł Palace in Poznań. The composer’s likeness appeared in symbolic representations of a psychological, ethnological and historical character. Traditional roots are referred to in the paintings of Feliks Wygrzywalski, Mazurek - grający Chopin [Mazurka - Chopin at the piano], with a couple of dancers in folk costume, and Stanisław Zawadzki, depicting the com poser with a roll of paper in his hand against the background of a forest, into the wall of which silhouettes of country children are merged, personifying folk music. Pictorial tales about music were also popularised by postcards. On one anonymous postcard, a ghost hovers over the playing musician, and the title Marsz żałobny Szopena [Chopin’s funeral march] suggests the connection with real apparitions that the composer occasional had when performing that work. In the visualisation of music, artists were often assisted by poets, who suggested associations and symbols. Correlations of content and style can be discerned, for ex ample, between Władysław Podkowinski’s painting Marsz żałobny Szopena and Kor nel Ujejski’s earlier poem Marsz pogrzebowy [Funeral march]. -

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His Broadcasting Career Covers Both Radio and Television

557643bk VW US 16/8/05 5:02 pm Page 5 8.557643 Iain Burnside Songs of Travel (Words by Robert Louis Stevenson) 24:03 1 The Vagabond 3:24 The English Song Series • 14 DDD Iain Burnside enjoys a unique reputation as pianist and broadcaster, forged through his commitment to the song 2 Let Beauty awake 1:57 repertoire and his collaborations with leading international singers, including Dame Margaret Price, Susan Chilcott, 3 The Roadside Fire 2:17 Galina Gorchakova, Adrianne Pieczonka, Amanda Roocroft, Yvonne Kenny and Susan Bickley; David Daniels, 4 John Mark Ainsley, Mark Padmore and Bryn Terfel. He has also worked with some outstanding younger singers, Youth and Love 3:34 including Lisa Milne, Sally Matthews, Sarah Connolly; William Dazeley, Roderick Williams and Jonathan Lemalu. 5 In Dreams 2:18 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His broadcasting career covers both radio and television. He continues to present BBC Radio 3’s Voices programme, 6 The Infinite Shining Heavens 2:15 and has recently been honoured with a Sony Radio Award. His innovative programming led to highly acclaimed 7 Whither must I wander? 4:14 recordings comprising songs by Schoenberg with Sarah Connolly and Roderick Williams, Debussy with Lisa Milne 8 Songs of Travel and Susan Bickley, and Copland with Susan Chilcott. His television involvement includes the Cardiff Singer of the Bright is the ring of words 2:10 World, Leeds International Piano Competition and BBC Young Musician of the Year. He has devised concert series 9 I have trod the upward and the downward slope 1:54 The House of Life • Four poems by Fredegond Shove for a number of organizations, among them the acclaimed Century Songs for the Bath Festival and The Crucible, Sheffield, the International Song Recital Series at London’s South Bank Centre, and the Finzi Friends’ triennial The House of Life (Words by Dante Gabriel Rossetti) 26:27 festival of English Song in Ludlow. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

Diplomacy World #131, Fall 2015 Issue

Notes from the Editor Welcome to the latest issue of Diplomacy World, the http://www.amazon.com/Art-Correspondence-Game- Fall 2015 issue. This is the 35th issue we produced Diplomacy-ebook/dp/B015XAJFM0 since I returned as Lead Editor back in 2007. It doesn’t really seem that long ago; it feels more like two or three Or there was a recent article in The Independent by Sam years instead of nearly nine. Kitchener which gave a fair and entertaining description of the game: The hobby was much different in 2007 than it was during my first term as Lead Editor (about ten years earlier) and http://www.independent.co.uk/extras/puzzles-and- it has continued to evolve during this stint. Sometimes I games/treachery-s-the-way-to-win-at-diplomacy-which- feel very connected to the hobby and what is going on, makes-it-just-like-the-real-thing-10485417.html and at other times I feel like I am completely out of the loop. New conventions, new websites, new hobby Both are recommended reading, by the way. groups…some of the older ones fade away and are replaced by new ones. But as I was saying, sometimes I feel a little out of touch. So I encourage each of you reading this to send me an email, even a short one. What I’d like are answers to a few simple questions: 1. I would like to see more of this type of article in Diplomacy World: _______ 2. I think Diplomacy World has too much of this type of article: _________ 3. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

Spring 2019 NEWSLETTER : BULLETIN Printemps 2019

Société d' Opéra National Capital de la Capitale Nationale Opera Society Spring 2019 NEWSLETTER : BULLETIN Printemps 2019 Announcing Increased Prize Money for the 2019 Brian Law Opera Competition We are delighted to announce a 40% increase in prize money. This year a total of $14,750 is available to be awarded to the finalists as follows: 1st prize: $7500 2nd prize: $3500 3rd prize: $1500 other finalists will receive $750 Another exciting change is to an afternoon competition. We hope that the change to the afternoon will be attractive to our audience and boost attendance. The 14th Brian Law Opera Competition (BLOC) will be held at 2:00 pm on Saturday, 19th October 2019 at the Southminster United Church, 15 Aylmer Avenue, Ottawa. At the last Competition, Southminster partnered with us by making the Competi- tion part of their Saturday concert series. Although the church has not as yet made plans for a concert series next season, we would welcome their partnership. The BLOC is our major activity, so the prizes are the best possible use of our funds. Mark your calendars and we’ll look forward to seeing you on October 19th. Mark Robinson Spring 2019 Printemps 2019 President's Message March 2019 by Murray Kitts It’s a lovely Spring day in Victoria, with sun- 1605 Requiem as well as Passiontide motets by shine and blossoms everywhere just like it was Renaissance masters. in January before winter reappeared. I’ve en- As for the simulcasts from the Met, I missed joyed a number of fine concerts here principally so many last season due to poor health but was because they have been presented on Sunday glad to see a repeat of La fille du regiment, more afternoons usually at the excellent auditorium at delightful every time I see it.