The Piano Etudes of David Rakowski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

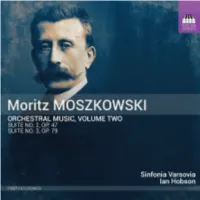

TOCC0557DIGIBKLT.Pdf

MORITZ MOSZKOWSKI: ORCHESTRAL MUSIC, VOLUME TWO by Martin Eastick History has not served Moszkowski well. Even before his death in 1925, his star had been on the wane for some years as the evolving ‘Brave New World’ took hold after the Great War in 1918: there was little or no demand for what Moszkowski once had to offer and the musical sensitivities he represented. His name did live on to a limited extent, with the odd bravura piano piece relegated to the status of recital encore, and his piano duets – especially the Spanish Dances – continuing to be favoured in the circles of home music-making. But that was about the limit of his renown until, during the late 1960s, there gradually awoke an interest in nineteenth-century music that had disappeared from the repertoire – and from people’s awareness – and the composers who had been everyday names during their own lifetime, Moszkowski among them. Initially, this ‘Romantic Revival’ was centred mainly on the piano, but it gradually diversified to music in all its forms and continues to this day. Only very recently, though, has attention been given to Moszkowski as a serious composer of orchestral music – with the discovery and performance in 2014 of his early but remarkable ‘lost’ Piano Concerto in B minor, Op. 3, providing an ideal kick-start,1 and the ensuing realisation that here was a composer worthy of serious consideration who had much to offer to today’s listener. In 2019 the status of Moszkowski as an orchestral composer was ramped upwards with the release of the first volume in this Toccata Classics series, featuring his hour-long, four-movement symphonic poem Johanna d’Arc, Op. -

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

¿Cuál Chopin? *

¿CUÁL CHOPIN? * Thomas Higgins Hoy día, los pianistas tienen a su disposición un gran número de edicio nes musicales de Chopin. En este artículo -descriptivo y analítico- serán exami nadas sólo las ediciones de mayor circulación o las que tengan un específico interés académico. Bajo este criterio podemos agrupar más de media docena de ediciones: l . Las Obras Completas de Fryderyk Chopin (Varsovia-Cracovia: Publicaciones de Música Polaca, 1949), a la que nos referiremos de ahora en adelante como la Edición Polaca Completa. Veintiséis volúmenes editados por Paderewsi0 , Bronarski y Turcinski. 2. La Edición Nacional Polaca (Varsovia: Przedstawicielstwo Wydawructwo Polskich, 1967). Baladas editadas por Jan Ekier. 3. La Edición Wiener Vrtext (Viena: Edición Universal, 19 3). Preludios edi tados por Bemard Hansen, con guías interpretativas de Jorg Demus; Estudio op.lO y 25. n'oís Nouvelles Etudes editados por Paul Badura Skoda; Impromp tus y Scherzos editados por Jan Ekier. 4. La Edición Henle Vrtext (Duisburg-Munich:Henle erlag, 195 . Doce volúmenes; el primero, agotado, y el último, editado por Ewald Zimmennan. 5. Dos colecciones de Schi.nner, una editada por Karol MiJnili , -posiblemente reimpresión de su edición para Kistner (Leipzig, 18 9: 1 vol. y Leipzig, 1 17 vol.-), por ejemplo: Preludios, copyright de Schimler 191-; l:l otr:I. editada por Rafael Joseffy, por ejemplo: los Estudios copyright de hirmer 1 1 . • Wbose ChoPin? 19th Ccntul)/ Music 1981. 01. ,pag. QUODLIBET éstas hay que añadir una última, muy inferior, casi un libelo, que es la edición de los Estudios, por Arthur Friedheim. A pesar de su ínfima calidad, Schrirmer aftrma en su Music Teacher's Pocket Memo Book de 1977 que fue la quinta edición más vendida de las músicas para piano. -

Pastiche for Piano on Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji Op 6 Sheet Music

Pastiche For Piano On Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji Op 6 Sheet Music Download pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 4 pages partial preview of pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2619 times and last read at 2021-09-28 10:12:03. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Method, Piano Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Opus Calidoscopium In Memory Of Sorabji Op 2 Opus Calidoscopium In Memory Of Sorabji Op 2 sheet music has been read 3180 times. Opus calidoscopium in memory of sorabji op 2 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-26 19:02:59. [ Read More ] Pastiche 2017 Pastiche 2017 sheet music has been read 2663 times. Pastiche 2017 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 02:51:33. [ Read More ] Virtuoso Etude No 4 In Memory Of Sorabji Nocturne Op 1 Virtuoso Etude No 4 In Memory Of Sorabji Nocturne Op 1 sheet music has been read 2729 times. Virtuoso etude no 4 in memory of sorabji nocturne op 1 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 05:00:02. -

A Scientific Characterization of Trumpet Mouthpiece Forces in the Context of Pedagogical Brass Literature

A SCIENTIFIC CHARACTERIZATION OF TRUMPET MOUTHPIECE FORCES IN THE CONTEXT OF PEDAGOGICAL BRASS LITERATURE James Ford III, B.M., M.M., M.M.E. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2007 APPROVED: Kris Chesky, Committee Chair Gene Cho, Minor Professor Leonard Candelaria, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Ford III, James, A Scientific Characterization of Trumpet Mouthpiece Forces in the Context of Pedagogical Brass Literature. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), December 2007, 61 pp., 7 tables, 2 graphs, references, 52 titles. Embouchure dysfunctions, including those from acute injury to the obicularis oris muscle, represent potential and serious occupational health problems for trumpeters. Forces generated between the mouthpiece and lips, generally a result of how a trumpeter plays, are believed to be the origin for such problems. In response to insights gained from new technologies that are currently being used to measure mouthpiece forces, belief systems and teaching methodologies may need to change in order to resolve possible conflicting terminology, pedagogical instructions, and performance advice. As a basis for such change, the purpose of this study was to investigate, develop and propose an operational definition of mouthpiece forces applicable to trumpet pedagogy. The methodology for this study included an analysis of writings by selected brass pedagogues regarding mouthpiece force. Finding were extracted, compared, and contrasted with scientifically derived mouthpiece force concepts developed from scientific studies including one done at the UNT Texas Center for Music & Medicine. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions. -

Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century," Edited by Roberto Illiano and Michela Niccolai Clive Brown University of Leeds

Performance Practice Review Volume 21 | Number 1 Article 2 "Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century," edited by Roberto Illiano and Michela Niccolai Clive Brown University of Leeds Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Performance Commons, and the Other Music Commons Brown, Clive (2016) ""Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century," edited by Roberto Illiano and Michela Niccolai," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 21: No. 1, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.201621.01.02 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol21/iss1/2 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book review: Illiano, R., M. Niccolai, eds. Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century. Turnhout: Brepols, 2014. ISBN: 9782503552477. Clive Brown Although the title of this book may suggest a comprehensive study of nineteenth- century conducting, it in fact contains a collection of eighteen essays by different au- thors, offering a series of highlights rather than a broad and connected picture. The collection arises from an international conference in La Spezia, Italy in 2011, one of a series of enterprising and stimulating annual conferences focusing on aspects of nineteenth-century music that has been supported by the Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini (Lucca), in this case in collaboration with the Società di Concerti della Spezia and the Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de musique romantique française (Venice). -

Part 3- a Sequential Approach to Etudes

Part Three: A Sequential Approach to Etudes by Robert Jesselson The first two parts of this series discussed the benefits of employing an organized and sequential approach for teaching the intermediate string player. With this method the string teacher can create a solid technical and musical foundation for the student, and avoid skipping over important information that will be required for his/her future growth. Part One explored the complex set of skills, knowledge and experiences that a developing string player needs to acquire in order to become a competent musician and creative artist. Part Two of this series discussed the use of organized exercises to address specific aspects of the technique. These exercises, along with the ubiquitous scales and arpeggios that musicians need to master, are the basic building blocks of technique. Etudes then expand on the micro-technique of the exercises. They begin to put the technical pieces together into musical shapes, and should be approached both technically and musically. The current article will explore the importance of providing a good sequence of etudes in order to solidify the technique and facilitate the learning of literature. The repertoire of cello etudes is large and varied, with many excellent studies from which to choose. Besides Duport, Dotzauer, Lee, Popper, Franchomme, Piatti, and Servais, we have etudes by Gruetzmacher, Kummer, Klengel, Merk as well as contemporary etudes by Minsky and others. There are also collections of etudes compiled by pedagogues such as Alwin Schroeder. Although I use individual etudes by all of these composers to address specific issues, I prefer to use a succession of complete etude books in order to immerse the students in a specific technical and stylistic approach by one composer at a time. -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting.