5069883-Deb527-5060113445728

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TOCC0557DIGIBKLT.Pdf

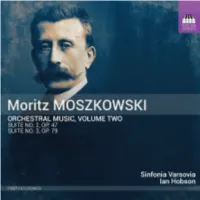

MORITZ MOSZKOWSKI: ORCHESTRAL MUSIC, VOLUME TWO by Martin Eastick History has not served Moszkowski well. Even before his death in 1925, his star had been on the wane for some years as the evolving ‘Brave New World’ took hold after the Great War in 1918: there was little or no demand for what Moszkowski once had to offer and the musical sensitivities he represented. His name did live on to a limited extent, with the odd bravura piano piece relegated to the status of recital encore, and his piano duets – especially the Spanish Dances – continuing to be favoured in the circles of home music-making. But that was about the limit of his renown until, during the late 1960s, there gradually awoke an interest in nineteenth-century music that had disappeared from the repertoire – and from people’s awareness – and the composers who had been everyday names during their own lifetime, Moszkowski among them. Initially, this ‘Romantic Revival’ was centred mainly on the piano, but it gradually diversified to music in all its forms and continues to this day. Only very recently, though, has attention been given to Moszkowski as a serious composer of orchestral music – with the discovery and performance in 2014 of his early but remarkable ‘lost’ Piano Concerto in B minor, Op. 3, providing an ideal kick-start,1 and the ensuing realisation that here was a composer worthy of serious consideration who had much to offer to today’s listener. In 2019 the status of Moszkowski as an orchestral composer was ramped upwards with the release of the first volume in this Toccata Classics series, featuring his hour-long, four-movement symphonic poem Johanna d’Arc, Op. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Turismus V Bydhošti. Kulturní a Jazykové Bariéry

VYSOKÁ ŠKOLA POLYTECHNICKÁ JIHLAVA Obor: Cestovní ruch Turismus v Bydhošti. Kulturní a jazykové bariéry bakalářská práce Autor: Miroslav Danko Vedoucí práce: RNDr. Jitka Ryšková Jihlava 2013 Prohlašuji, že předložená bakalářská práce je původní a zpracoval jsem ji samostatně. Prohlašuji, že citace použitých pramenů je úplná, že jsem v práci neporušil autorská práva (ve smyslu zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů, v platném znění, dále též „AZ“). Souhlasím s umístěním bakalářské práce v knihovně VŠPJ a s jejím užitím k výuce nebo k vlastní vnitřní potřebě VŠPJ . Byl jsem seznámen s tím, že na mou bakalářskou práci se plně vztahuje AZ, zejména § 60 (školní dílo). Beru na vědomí, že VŠPJ má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití mé bakalářské práce a prohlašuji, že s o u h l a s í m s případným užitím mé bakalářské práce (prodej, zapůjčení apod.). Jsem si vědom toho, že užít své bakalářské práce či poskytnout licenci k jejímu využití mohu jen se souhlasem VŠPJ, která má právo ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, vynaložených vysokou školou na vytvoření díla (až do jejich skutečné výše), z výdělku dosaženého v souvislosti s užitím díla či poskytnutím licence. V Jihlavě dne 10. května 2013 ...................................................... Podpis I would like to express my gratitude towards my supervisor RNDr. Jitka Ryšková for her help with my bachelor thesis. I am greatful for the time she spent supervising my work and all of the advice she give me. I wish to thank Mr. Jan Karol Słowinski who supervised and helped me with my thesis during my stay in Poland. -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

Choral & Classroom

2020–2021 CHORAL & CLASSROOM MORE TO EXPLORE DIGITAL AND ONLINE CHORAL RESOURCES ENHANCE YOUR REVIEW Watch Score & Sound videos Stream or download View or download full to see the music while the full performance PDFs for recording plays. recordings. each voicing. ENHANCE YOUR PRACTICE Use the practice tools and repertoire in SmartMusic to help singers grow and develop. ENHANCE YOUR PERFORMANCE Staging videos for select titles SoundTrax accompaniments PianoTrax accompaniments are are available online. are available online. available individually online. Visit alfred.com/newchoral 2 WELCOME TABLE OF CONTENTS Alfred Choral Designs General Concert & Contest ...........................6 Spirituals .................................................8 Masterworks ............................................9 Dear Music Educator, Folk Songs & World Music .......................... 10 Holiday / Seasonal ....................................11 This is a true story. It was a few decades ago when I first fell in love with Alfred Alfred Pop Series Music’s choral promotion. For real. I noticed the colorful catalog stacked on my Holiday Pop .............................................13 high school music teacher’s inbox and my eyes lit up. Mr. Paine (a great mentor) Current Pop .............................................14 must have sensed my delight, because he offered to loan it out over the weekend. Classic Pop ..............................................14 I was thrilled. I could not wait to get that plastic cassette tape home to my shoebox Contemporary -

MUSIC LIST Email: Info@Partytimetow Nsville.Com.Au

Party Time Page: 1 of 73 Issue: 1 Date: Dec 2019 JUKEBOX Phone: 07 4728 5500 COMPLETE MUSIC LIST Email: info@partytimetow nsville.com.au 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 100 PERCENT PURE LOVE by Crystal Waters 1000 STARS by Natalie Bassingthwaighte {Karaoke} 11 MINUTES by Yungblud - Halsey 1979 by Good Charlotte {Karaoke} 1999 by Prince {Karaoke} 19TH NERVIOUS BREAKDOWN by The Rolling Stones 2 4 6 8 MOTORWAY by The Tom Robinson Band 2 TIMES by Ann Lee 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 21 - GUNS by Greenday {Karaoke} 21 QUESTIONS by 50 Cent 22 by Lilly Allen {Karaoke} 24K MAGIC by Bruno Mars 3 by Britney Spears {Karaoke} 3 WORDS by Cheryl Cole {Karaoke} 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 EVER by The Veronicas {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 4 MINUTES by Madonna And Justin 40 MILES OF ROAD by Duane Eddy 409 by The Beach Boys 48 CRASH by Suzi Quatro 5 6 7 8 by Steps {Karaoke} 500 MILES by The Proclaimers {Karaoke} 60 MILES AN HOURS by New Order 65 ROSES by Wolverines 7 DAYS by Craig David {Karaoke} 7 MINUTES by Dean Lewis {Karaoke} 7 RINGS by Ariana Grande {Karaoke} 7 THINGS by Miley Cyrus {Karaoke} 7 YEARS by Lukas Graham {Karaoke} 8 MILE by Eminem 867-5309 JENNY by Tommy Tutone {Karaoke} 99 LUFTBALLOONS by Nena 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A B C by Jackson 5 A B C BOOGIE by Bill Haley And The Comets A BEAT FOR YOU by Pseudo Echo A BETTER WOMAN by Beccy Cole A BIG HUNK O'LOVE by Elvis A BUSHMAN CAN'T SURVIVE by Tania Kernaghan A DAY IN THE LIFE by The Beatles A FOOL SUCH AS I by Elvis A GOOD MAN by Emerson Drive A HANDFUL -

Connected by Music Dear Friends of the School of Music

sonorities 2021 The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music Connected by Music Dear Friends of the School of Music, Published for the alumni and friends of the ast year was my first as director of the school and as a member School of Music at the University of Illinois at of the faculty. It was a year full of surprises. Most of these Urbana-Champaign. surprises were wonderful, as I was introduced to tremendously The School of Music is a unit of the College of Lcreative students and faculty, attended world-class performances Fine + Applied Arts and has been an accredited on campus, and got to meet many of you for the first time. institutional member of the National Association Nothing, however, could have prepared any of us for the of Schools of Music since 1933. changes we had to make beginning in March 2020 with the onset of COVID-19. Kevin Hamilton, Dean of the College of Fine + These involved switching our spring and summer programs to an online format Applied Arts with very little notice and preparing for a fall semester in which some of our activi- Jeffrey Sposato, Director of the School of Music ties took place on campus and some stayed online. While I certainly would never Michael Siletti (PhD ’18), Editor have wished for a year with so many challenges, I have been deeply impressed by Design and layout by Studio 2D the determination, dedication, and generosity of our students, faculty, alumni, and On the cover: Members of the Varsity Men’s Glee friends. -

By Malcolm Hayes Liszt

by Malcolm Hayes Liszt !"##!$%&'%#()*+,-.)*/0(123(45+*6(7889:0-(-0;-(<=.>.%="*233(((< =#?%=?$=%=(((%#@#$ © 2011 Naxos Rights International Ltd. www.naxos.com Design and layout: Hannah Davies, Fruition – Creative Concepts Edited by Ingalo !omson Front cover picture: Franz Liszt by Chai Ben-San Front cover background picture: courtesy iStockphoto All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Naxos Rights International Ltd. ISBN: 978-1-84379-248-2 !"##!$%&'%#()*+,-.)*/0(123(45+*6(7889:0-(-0;-(<=.>.%="*233(((& =#?%=?$=%=(((%#@#$ Contents 7 Author’s Acknowledgements 8 CD Track Lists 12 Website 13 Preface 19 Chapter 1: !e Life, 1811–1847: From Prodigy to Travelling Virtuoso 45 Chapter 2: !e Music, 1822–1847: !e Lion of the Keyboard 61 Chapter 3: !e Life, 1847–1861: Weimar 84 Chapter 4: !e Music, 1847–1861: Art and Poetry 108 Chapter 5: !e Life, 1861–1868: Rome 125 Chapter 6: !e Music, 1861–1868: Urbi et orbi 141 Chapter 7: !e Life, 1869–1886: ‘Une vie trifurquée’ 160 Chapter 8: !e Music, 1869–1886: ‘A spear thrown into the future…’ 177 Epilogue 184 Personalities 199 Selected Bibliography 201 Glossary 209 Annotations of CD Tracks 219 About the Author !"##!$%&'%#()*+,-.)*/0(123(45+*6(7889:0-(-0;-(<=.>.%="*233(((# =#?%=?$=%=(((%#@#$ Acknowledgements 7 Author’s Acknowledgements Anyone writing about Liszt today is fortunate to be doing so after the appearance of Alan Walker’s monumental three-volume biography of the composer. !e outcome of many years of research into French, German, Hungarian and Italian sources, Professor Walker’s work has set a new standard of accuracy in Liszt scholarship. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1980

- wm /j ^CHAM?^ iir ?**»»« hl ,(t«ll <Ma4^4m^mf7$f i$i& Vs^Qp COGNAC W****** B r jfi>AV., RY y -^^COgJi INf :<k champacni: < THE FIRST NAME IN COGNAC SINCE 1724 /ELY F.INI CHAYf PAGNJi COGNAC: IKUV1 IHI TWO "PREMIERS CRUS" OF fHFi COGNAC REGION BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA A Music Director \K , vft Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Sir Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor Ninety-Ninth Season, 1979-80 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Talcott M. Banks, Chairman Nelson J. Darling, Jr., President Philip K. Allen, Vice-President Sidney Stoneman, Vice-President Mrs. Harris Fahnestock, Vice-President John L. Thorndike, Vice-President Roderick M. MacDougall, Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Archie C. Epps III Thomas D. Perry, Jr. Allen G. Barry E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Irving W. Rabb Leo L. Beranek Edward M. Kennedy Paul C. Reardon Mrs. John M. Bradley George H. Kidder David Rockefeller, Jr. George H.A. Clowes, Jr. Edward G. Murray Mrs. George Lee Sargent Abram T. Collier Albert L. Nickerson John Hoyt Stookey Trustees Emeriti Richard P. Chapman John T. Noonan Mrs. James H. Perkins Administration of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Thomas W. Morris General Manager Peter Gelb Gideon Toeplitz Daniel R. Gustin Assistant Manager Orchestra Manager Assistant Manager Joseph M. Hobbs Walter D. Hill William Bernell Director of Director of Assistant to the Development Business Affairs General Manager Caroline E. Hessberg Dorothy Sullivan Anita R. Kurland Promotion Administrator Controller of Coordinator Youth Activities Joyce M. Snyder Richard Ortner Elisabeth Quinn Development Assitant Administrator, Director of Coordinator Berkshire Music Center Volunteer Services Elizabeth Dunton James E. -

Depaul Symphony Orchestra

Friday, February 2, 2018 • 8:00 P.M. DEPAUL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Cliff Colnot, conductor DePaul Concert Hall 800 West Belden Avenue • Chicago Friday, February 2, 2018 • 8:00 P.M. DePaul Concert Hall DEPAUL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Cliff Colnot, conductor PROGRAM Moritz Moszkowski (1854-1925); arr. Carl Topilow Suite for 2 Violins and Orchestra, Op. 71 (1903) Allegro energico Allegro moderato Lento assai Moto vivace Ilya Kaler, violin Olga Dubossarskaya Kaler, violin Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Symphony No. in C Minor, Op. 67 (1808) Allegro con brio Andante con moto Scherzo: Allegro Allegro DEPAUL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA • FEBRUARY 2, 2018 PROGRAM NOTES Moritz Moszkowski; arr. Carl Topilow Suite for 2 Violins and Orchestra, Op. 71 Duration: 22 minutes Of Moritz Moszkowski’s death in April 1925, a report declared, “So painful an announcement has not stricken the entire musical world since the deaths of Chopin, Rubinstein, and Liszt, of whom he was a worthy successor.” Yet how did the music of this man, included in such a legacy of composers, end up so little known today? One may not find the answer but instead can be encouraged to dig deep and unearth hidden treasures such as this one. Moszkowski was born in Breslau, Prussia (now Wrocław, Poland) and received musical lessons at home before training at conservatories in Dresden and Berlin, including the Stern Conservatory and Theodore Kullak’s Neue Akademie der Tonkunst. He was only seventeen when he accepted Kullak’s invitation to join the staff at this academy, where he taught for over twenty-five years. In 1873 he made his successful début in Berlin as a pianist and just two years later was invited by Liszt to give a concert together. -

Neue Cds: Vorgestellt Von Doris Blaich

Freitag, 08.04.2016 SWR2 Treffpunkt Klassik – Neue CDs: Vorgestellt von Doris Blaich Esprit, Leidenschaft und Ernsthaftigkeit „Conversations“ Ensemble Nevermind Quartette von Jean-Baptiste Quentin und Louis-Gabriel Guillemain ALPHA 235 Sprudelnde Energie Robert Schumann: Cellokonzert a-Moll op. 129 Klaviertrio Nr. 1 d-Moll op. 63 Jean-Guihen Queyras, Violoncello Isabelle Faust, Violine Alexander Melnikov, Fortepiano Freiburger Barockorchester Pablo Heras-Casado HMC 902197 Großer Atembogen Johann Sebastian Bach: Lass, Fürstin, lass noch einen Strahl BWV 198 Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden BWV 1083 Bach Collegium Japan Leitung: Masaaki Suzuki BIS 2181 Unglaubliche Virtuosität Philipp Scharwenka: Werke für Violine und Klaiver Sonate h-Moll op. 110 Sonate e-Moll op. 114 Suite op. 99 für Violine und Klavier Natalia Prischepenko, Violine Oliver Triendl, Klavier TYX Art 16075 Freude und Sorgfalt am Detail Antonín Dvořák: Sinfonien Nr. 7 und 8 Houston Symphony Andrés Orozco-Estrada PENTATONE PTC 5186 578 Signet Treffpunkt Klassik – neue CDs ... mit Doris Blaich, herzlich willkommen! Ein Befreiungschlag! – sagt der Cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras über sein Erlebnis, das Cellokonzert von Robert Schumann zusammen mit einem Orchester zu spielen, das auf historischen Instrumenten musiziert. Plötzlich lösen sich alle Schwerfälligkeiten wie von selbst. Die CD mit Queyras und dem Freiburger Barockorchester erscheint nächste Woche, heute können Sie hier schon mal reinhören. 1 Und ich habe noch vier weitere CDs dabei: Barocke Kammermusik aus Frankreich, die von der Idee einer geistreichen und kultivierten Unterhaltung lebt – eine Art musikalischer Gesprächsknigge also; dann Bachs Trauerode auf die sächsische Kurfürstin Christiane Eberhardine, aufgenommen vom Bach-Collegium Japan und Masaaki Suzuki, Violinsonaten von Philipp Scharwenka, ein Komponist der Romantik, den heute praktisch keiner mehr kennt, der aber eine Entdeckung lohnt.