A the Unfinished Dialogue of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr

THE PAPERS OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. Initiated, by The King Center in association with Stanford University After a request to negotiate with the Albany City Commission on 27July 1962 was denied, King, Ralph Abernathy, William G. Anderson, and seven others are escorted to jail by Police Chief Laurie Pritchett for disorderly conduct, congregating on the sidewalk, and disobeying a police officer. © Corbis. THE PAPERS OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. VOLUME VII To Save the Soul of America January 1961-August 1962 Senior Editor Clayborne Carson Volume Editor Tenisha Armstrong UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr., © 2014 by the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr. Introduction, editorial footnotes, and apparatus © 2014 by the Martin Luther King, Jr., Papers Project. © 2014 by The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address queries as appropriate to: Reproduction in print or recordings of the works of Martin Luther King, Jr.: the Estate of Martin Luther KingJr., in Atlanta, Georgia. All other queries: Rights Department, University of California Press, Oakland, California. -

João Pedro Valladão Pinheiro Improving the Quality of the User

João Pedro Valladão Pinheiro Improving the Quality of the User Experience by Query Answer Modification Dissertação de Mestrado Dissertation presented to the Programa de Pós–graduação em Informática of PUC-Rio in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Mestre em Informática. Advisor : Prof. Marco Antonio Casanova Co-advisor: Profa. Elisa Souza Menendez Rio de Janeiro April 2021 João Pedro Valladão Pinheiro Improving the Quality of the User Experience by Query Answer Modification Dissertation presented to the Programa de Pós–graduação em Informática of PUC-Rio in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Mestre em Informática. Approved by the Examination Committee: Prof. Marco Antonio Casanova Advisor Departamento de Informática – PUC-Rio Profa. Elisa Souza Menendez Co-Advisor Campus Xique-Xique – Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia Baiano Prof. Antonio Luz Furtado Departamento de Informática – PUC-Rio Prof. Luiz André Portes Paes Leme Departamento de Ciências da Computação – UFF Rio de Janeiro, April 30th, 2021 All rights reserved. João Pedro Valladão Pinheiro João Pedro Valladão Pinheiro holds a bachelor degree in Computer Engineering from Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio). His main research topics are Semantic Web and Information Retrieval. Bibliographic data Pinheiro, João Pedro V. Improving the Quality of the User Experience by Query Answer Modification / João Pedro Valladão Pinheiro; advisor: Marco Antonio Casanova; co-advisor: Elisa Souza Menendez. – 2021. 55 f: il. color. ; 30 cm Dissertação (mestrado) - Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Departamento de Informática, 2021. Inclui bibliografia 1. Computer Science – Teses. 2. Informatics – Teses. 3. Pergunta e Resposta (QA). -

Newyork 08-1

Representative Hakeem Jeffries 117th United States Congress New York's 8TH Congressional District NUMBER OF DELIVERY SITES IN 37 CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT (main organization in bold) BEDFORD STUYVESANT FAMILY HEALTH CENTER, INC., THE Broadway Family Health Center - 1238 Broadway Brooklyn, NY 11221-2906 PS 256 - School Based Hlth Ctr - 114 Kosciuszko St Brooklyn, NY 11216-1007 PS 309 - School Based Hlth Ctr - 794 Monroe St Brooklyn, NY 11221-3501 PS 54 - School Based Hlth Ctr - 195 Sandford St Brooklyn, NY 11205-4525 BETANCES HEALTH CENTER Betances Health Center at Bushwick - 1427 Broadway Brooklyn, NY 11221-4202 BROOKLYN PLAZA MEDICAL CENTER Benjamin Banneker Academy Sbh - 77 Clinton Ave Brooklyn, NY 11205-2302 Whitman, Ingersoll, Farragut H C - 297 Myrtle Ave Brooklyn, NY 11205-2901 BROWNSVILLE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION BMS Dental@Genesis - 330 Hinsdale St Brooklyn, NY 11207-4518 BMS@Ashford - 650 Ashford St Brooklyn, NY 11207-7315 BMS@Genesis - 360 Snediker Ave Brooklyn, NY 11207-4552 BMS@Jefferson High School Campus - 400 Pennsylvania Ave Brooklyn, NY 11207-4707 CARE FOR THE HOMELESS Bushwick Family Residence - 1675 Broadway Brooklyn, NY 11207-1495 Care Found Here: Junius St - 91 Junius St Brooklyn, NY 11212-8021 St. John's Bread and Life - 795 Lexington Ave Brooklyn, NY 11221-2903 COMMUNITY HEALTHCARE NETWORK, INC. Dr Betty Shabazz Health Center - 999 Blake Ave Brooklyn, NY 11208-3535 Medical Mobile Van (3) - 999 Blake Ave Brooklyn, NY 11208-3535 Medical Mobile Van (4) - 999 Blake Ave Brooklyn, NY 11208-3535 FLOATING HOSPITAL INCORPORATED (THE) Auburn Assessment Center - 39 Auburn Pl Brooklyn, NY 11205-1946 Flatlands - 10875 Avenue D Brooklyn, NY 11236-1931 Help I Family Center - 515 Blake Ave Brooklyn, NY 11207-4502 HOUSING WORKS HEALTH SERVICES III, INC. -

Extensions of Remarks E1775 HON. SAM GRAVES HON

December 10, 2014 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1775 On a personal note, Aubrey was a dear son to ever serve in the House of Representa- U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, U.S. Sen- friend and loyal supporter. I will always re- tives, the oldest person ever elected to a ator Lloyd Bentsen, T. Boone Pickens, H. member his kindness and his concern for peo- House term and the oldest House member Ross Perot, Red Adair, Bo Derek, Chuck Nor- ple who deserved a second chance. I will al- ever to a cast a vote. Mr. HALL is also the last ris, Ted Williams, Tom Hanks and The Ink ways remember him as a kind, gentle, loving, remaining Congressman who served our na- Spots. and brilliant human being who gave so much tion during World War II. He works well with both Republicans and to others. And for all of these accomplishments, I Democrats, but he ‘‘got religion,’’ in 2004, and Today, California’s 13th Congressional Dis- would like to thank and congratulate RALPH became a Republican. Never forgetting his trict salutes and honors an outstanding indi- one more time for his service to the country Democrat roots, he commented, ‘‘Being a vidual, Dr. Aubrey O’Neal Dent. His dedication and his leadership in the Texas Congressional Democrat was more fun.’’ and efforts have impacted so many lives Delegation. RALPH HALL always has a story and a new, throughout the state of California. I join all of Born in Fate, Texas on May 3, 1923, HALL but often used joke. -

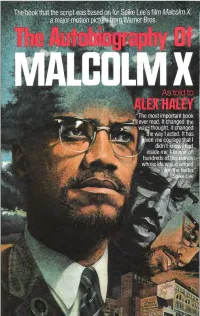

The-Autobiography-Of-Malcolm-X.Pdf

The absorbing personal story of the most dynamic leader of the Black Revolution. It is a testament of great emotional power from which every American can learn much. But, above all, this book shows the Malcolm X that very few people knew, the man behind the stereotyped image of the hate-preacher-a sensitive, proud, highly intelligent man whose plan to move into the mainstream of the Black Revolution was cut short by a hail of assassins' bullets, a man who felt certain "he would not live long enough to see this book appear. "In the agony of [his] self-creation [is] the agony of an entire.people in their search for identity. No man has better expressed his people's trapped anguish." -The New York Review of Books Books published by The Ballantine Publishing Group are available at quantity discounts on bulk purchases for premium, educational, fund-raising, and special sales use. For details, please call 1-800-733-3000. THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OFMALCOLMX With the assistance ofAlex Haley Foreword by Attallah Shabazz Introduction by M. S. Handler Epilogue by Alex Haley Afterword by Ossie Davis BALLANTINE BOOKS• NEW YORK Sale of this book without a front cover may be unauthorized. If this book is coverless, it may have been reported to the publisher as "unsold or destroyed" and neither the author nor the publisher may have received payment for it. A Ballantine Book Published by The Ballantine Publishing Group Copyright© 1964 by Alex Haley and Malcolm X Copyright© 1965 by Alex Haley and Betty Shabazz Introduction copyright© 1965 by M. -

124-130 WEST 125TH STREET up to Between Adam Clayton Powell Jr and Malcolm X Blvds/Lenox Avenue 22,600 SF HARLEM Available for Lease NEW YORK | NY

STREET RETAIL/RESTAURANT/QSR/MEDICAL/FITNESS/COMMUNITY FACILITY 3,000 SF 124-130 WEST 125TH STREET Up To Between Adam Clayton Powell Jr and Malcolm X Blvds/Lenox Avenue 22,600 SF HARLEM Available for Lease NEW YORK | NY ARTIST’S RENDERING 201'-10" 2'-0" 1'-4" 19'-5" 1'-5" 3" SLAB 2'-4" 21'-0" 8" 16'-1" 15'-6" 39'-9" 4'-9" 46'-0" 5'-5" DISPLAY CLG 1'-3" 5'-8" 40'-5" OFFICE 12'-0" 47'-7" B.B. 7'-1" 72'-6" 13'-2" D2 4'-4" 4'-0" 10'-2" 74'-2" 11'-4" 42'-3" 11'-2" 4'-9" 8'-4" 1'-3" 17'-6" 11" 2'-4" 138'-11" 5'-11" 1'-11" 7'-1" 147'-1" GROUND FLOOR GROUND 34'-9" 35'-1" 1'-4" 34'-8" 2x4 33'-10" 2x4 CLG. PARAMOUNT CLG. 12'-3" 124 W. 125 ST 11'-10" 24'-6" 23'-6" DISPLAY CTR 22'-11" D.H. 10'-10" 16'-0" 8'-11" 1'-4" 2'-5" 4'-2" GAS MTR EP EP ELEC 1'-5" 2'-10" 4" 7" 1'-4" 6" 1'-6" 11" 7'-0" 52'-0" 12'-11" 1'-2" CLG. 1'-10"1'-0" 3'-2" D2 10'-3" 36'-10" UP7" DN 11" 4'-8" 2x4 2'-3" 5'-3" DISPLAY CTR 13'-8" 6'-3" 7'-0" CLG. 7'-0" 7'-3" 7'-11" UP 11" 11'-8" 9'-10" 9'-10" AJS GOLD & DIAMONDS 2'-9" 6" 2x4 4" 7'-4" 126 W. 125 ST 2'-4" 2'-8" 2'-4" CLG. -

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Title of Lesson: the Courage Of

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Title of Lesson: The Courage of Direct Action through Nonviolence in the Montgomery Bus Boycott Lesson By: Cara McCarthy Grade Level/ Subject Areas: Class Size: Time/Duration of Lesson: Fourth Grade 20-25 1 – 2 days Guiding Questions: • Is nonviolence courageous? Do you think nonviolence is more or less courageous than violence? • What was the effect of direct action (the disciplined nonviolent use of the body to protest injustice) on the Montgomery bus boycott? • Did Martin Luther King, Jr. create the Black Freedom Movement or did the movement create Martin Luther King, Jr. ? Use the example of Rosa Parks to explain your thinking. • Explain how the legacy of Rosa Parks bears witness to many of Martin Luther King Jr’s principles of nonviolence including education, personal commitment and direct action. Lesson Abstract: The students will explore the power of nonviolence inspired by Gandhi and disseminated by Dr. Dr. King in the Black Freedom Movement, which demanded equal rights for all humanity regardless of race or ethnicity. They will explore the power of direct action, disciplined nonviolence as practiced by a group of people (individually or en masse) in order to achieve a political/social justice goal. They will explore the impact of individual contributions to the dismantling of segregation through the practice of direct action as illustrated by the historical contribution of Rosa Parks. Her arrest propelled Dr. King and his belief in the philosophy of nonviolent direct action to the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement. Lesson Content: Dr. King, the leader of the Black Freedom Movement in the United States of America, advocated and practiced nonviolence in response to the aggressive and violent actions perpetrated by a strict system of segregation. -

Waveland, Mississippi, November 1964: Death of Sncc, Birth of Radicalism

WAVELAND, MISSISSIPPI, NOVEMBER 1964: DEATH OF SNCC, BIRTH OF RADICALISM University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire: History Department History 489: Research Seminar Professor Robert Gough Professor Selika Ducksworth – Lawton, Cooperating Professor Matthew Pronley University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire May 2008 Abstract: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced Snick) was a nonviolent direct action organization that participated in the civil rights movement in the 1960s. After the Freedom Summer, where hundreds of northern volunteers came to participate in voter registration drives among rural blacks, SNCC underwent internal upheaval. The upheaval was centered on the future direction of SNCC. Several staff meetings occurred in the fall of 1964, none more important than the staff retreat in Waveland, Mississippi, in November. Thirty-seven position papers were written before the retreat in order to reflect upon the question of future direction of the organization; however, along with answers about the future direction, these papers also outlined and foreshadowed future trends in radical thought. Most specifically, these trends include race relations within SNCC, which resulted in the emergence of black self-consciousness and an exodus of hundreds of white activists from SNCC. ii Table of Contents: Abstract ii Historiography 1 Introduction to Civil Rights and SNCC 5 Waveland Retreat 16 Position Papers – Racial Tensions 18 Time after Waveland – SNCC’s New Identity 26 Conclusion 29 Bibliography 32 iii Historiography Research can both answer questions and create them. Initially I discovered SNCC though Taylor Branch’s epic volumes on the Civil Right Movements in the 1960s. Further reading revealed the role of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced Snick) in the Civil Right Movement and opened the doors into an effective and controversial organization. -

Aspects of the Civil Rights Movement, 1946-1968: Lawyers, Law, and Legal and Social Change (CRM)

Aspects of The Civil Rights Movement, 1946-1968: Lawyers, Law, and Legal and Social Change (CRM) Syllabus Spring 2012 (N867 32187) Professor Florence Wagman Roisman Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law Office Hours: Tuesdays and Wednesday – 11:00 a.m.- 12:00 p.m. Room 385 Roy Wilkins of the NAACP “reminded King that he owed his early fame to the NAACP lawsuit that had settled the Montgomery bus boycott, and he still taunted King for being young, naïve, and ineffectual, saying that King’s methods had not integrated a single classroom in Albany or Birmingham. ‘In fact, Martin, if you have desegregated anything by your efforts, kindly enlighten me.’ ‘Well,’ King replied, ‘I guess about the only thing I’ve desegregated so far is a few human hearts.’ King smiled too, and Wilkins nodded in a tribute to the nimble, Socratic reply. ‘Yes, I’m sure you have done that, and that’s important. So, keep on doing it. I’m sure it will help the cause in the long run.’” Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-1963 (Simon and Schuster 1988), p. 849. Welcome to this course in the Civil Rights Movement (CRM). I adore this course, as has almost every student who’s taken it when I’ve taught it before. I have four goals for the course: to increase and make more sophisticated our understanding of what actually happened during the CRM, to consider the various roles played by lawyers and the law in promoting (and hindering) significant social change, to see what lessons the era of the CRM suggests for apparently similar problems we face today, and to promote consideration of ways in which each of us can contribute to humane social change. -

Tone Parallels in Music for Film: the Compositional Works of Terence Blanchard in the Diegetic Universe and a New Work for Studio Orchestra By

TONE PARALLELS IN MUSIC FOR FILM: THE COMPOSITIONAL WORKS OF TERENCE BLANCHARD IN THE DIEGETIC UNIVERSE AND A NEW WORK FOR STUDIO ORCHESTRA BY BRIAN HORTON Johnathan B. Horton B.A., B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Richard DeRosa, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Murphy, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Jazz Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Horton, Johnathan B. Tone Parallels in Music for Film: The Compositional Works of Terence Blanchard in the Diegetic Universe and a New Work for Studio Orchestra by Brian Horton. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2017, 46 pp., 1 figure, 24 musical examples, bibliography, 49 titles. This research investigates the culturally programmatic symbolism of jazz music in film. I explore this concept through critical analysis of composer Terence Blanchard's original score for Malcolm X directed by Spike Lee (1992). I view Blanchard's music as representing a non- diegetic tone parallel that musically narrates several authentic characteristics of African- American life, culture, and the human condition as depicted in Lee's film. Blanchard's score embodies a broad spectrum of musical influences that reshape Hollywood's historically limited, and often misappropiated perceptions of jazz music within African-American culture. By combining stylistic traits of jazz and classical idioms, Blanchard reinvents the sonic soundscape in which musical expression and the black experience are represented on the big screen. -

Folly- and Faith-Of Furman

THE JOURNAL OF APPELLATE PRACTICE AND PROCESS FURMAN AT FORTY PREFACE THE FOLLY- AND FAITH-OF FURMAN John H. Blume* and Sheri Lynn Johnson** Justice Marshall's opinion in Furman v. Georgia memorably characterizes the abolition of capital punishment as "a major milestone in the long road up from barbarism."' For abolitionists today, it is surprising to recall that this phrase was not coined by Marshall, but borrowed from former Attorney General Ramsey Clark.2 That the chief law enforcement official of the United States might publicly condemn capital punishment is, from a modem perspective, almost unimaginable. Since then, we have seen one liberal presidential candidacy founder at least in part on resisting the lure of vengeance: Michael Dukakis's rejection of capital punishment even for a hypothesized murderer of his wife hurt him badly. We have also watched two purportedly liberal candidates hustle to support capital punishment in particularly dubious circumstances; Bill Clinton *Professor, Cornell Law School, and Director, Cornell Death Penalty Project. **James and Mark Flanagan Professor of Law, Cornell Law School, and Assistant Director, Cornell Death Penalty Project. 1. 408 U.S. 238, 370 (1972) (Marshall, J., concurring). 2. Ramsey Clark, Crime in America 336 (Simon & Schuster 1970). THE JOURNAL OF APPELLATE PRACTICE AND PROCESS Vol. 13, No. 1 (Spring 2012) THE JOURNAL OF APPELLATE PRACTICE AND PROCESS left the campaign trail to sign the death warrant of a man so mentally impaired by a self-inflicted gunshot wound that he didn't understand dying,3 and Barack Obama joined the clamor against a (conservative) Supreme Court's decision that imposition of the death penalty for child rape is unconstitutional.4 But back in Furman's day, it was politically possible to condemn capital punishment. -

The Temple Murals: the Life of Malcolm X by Florian Jenkins

THE TEMPLE MURALS: THE LIFE OF MALCOLM X BY FLORIAN JENKINS HOOD MUSEUM OF ART | CUTTER-SHABAZZ ACADEMIC AFFINITY HOUSE | DARTMOUTH COLLEGE PREFACE The Temple Murals: The Life of Malcolm X by Florian Arts at Dartmouth on January 25, 1965, just one month a bed of grass, his head lifted in contemplation; across Jenkins has been a Dartmouth College treasure for before his tragic assassination. Seven years later, the room, above the fireplace, his face appears in many forty years, and we are excited to reintroduce it with the students in the College’s Afro-American Society invited angles and perspectives, with colors that are not absolute publication of this brochure, the research that went into Jenkins to create a mural in their affinity house, which but nuanced, suggesting the subject’s inner mysteries its contents, and the new photographs of the murals that they had just rededicated as the El Hajj Malik El Shabazz and anxieties, reflecting our own. illustrate it. Painted during a five-month period in 1972 Temple, after the name and title that Malcolm X had The murals also point out how starkly we differ from in the Cutter-Shabazz affinity house at Dartmouth, the adopted in 1964 after returning from his pilgrimage in Malcolm, who is rendered in contrasts in color, especially mural speaks to a potent moment in American history, Mecca. Now under the care of the Hood Museum of Art, above the door threshold. A white-masked specter one connected to events both in the life of civil rights The Temple Murals are powerful works that remind us of stands behind a black gunman, holding the gun toward leader Malcolm X and the moment of Dartmouth history the strength of individual activist voices, which Jenkins Malcolm as a horrified, blurred-face bystander watches in which the mural was created.